POETRY NORTHWEST: SUMMER 2000

VOLUME FORTY-ONE NUMBER TWO

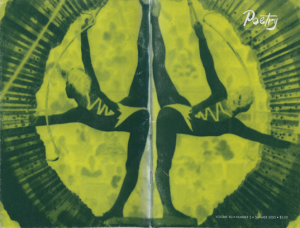

Editor: David Wagoner Cover from a photo of a balancing act in the Ringling Brothers, Barnum & Bailey Circus Photo by Robin Sqyjried POETRY NORTHWEST SUMMER 2000 VOLUME XLI, NUMBER 2 Published quarterly by the University of Washington, A101 Padelford, Box 354330, Seattle, WA 98195-4330. Subscriptions and manuscripts should be sent to Poetry Northwest, Department of English, Box 354330, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195-4330. Not responsible for unsolicited manuscripts; all submissions must be accompanied by a stamped self-addressed envelope. Subscription rates: U.S., $15.00 ger ye2(1r, single copies $5.00; Foreign and Canadian, $17.00 (U.S .) per year, single copies 5.50 U.S. . Periodicals postage paid at Seattle, Washington. POSTMASTER: Send address change: to Poetry Northwest, Box 354330, University of Washington, Seattle, W4 98195-4330 Published by the University of Washington ISSN: 0032-2113TABLE OF CONTENTS

TINA KELLEY

Five Poems . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 03

THOMAS BRUSH

Teaching . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .11

KATHLEEN LYNCH

Torn Bird . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12

FLOYD SKLOOT

Three Poems . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13

THOM SCHRAMM

Poet Anonymous . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16

MICHAEL CADNUM

Tide . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .17

SUSAN BLACKWELL RAMSEY

Three Poems . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .19

JANE EKLUND

Thumbs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21

LYNN DOMINA

Love Poem Relying on an Ethnographer’s Myth . . . . . . . . 22

HARRY HUMES

Three Poems . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 23

WILLIAM GREENWAY

A Woman Brought to Child . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 26

JULIE LARIOS

What I Imagine While Riding the Ferry . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 28

JILL E. THOMAS

Elemental . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 29

KENNETH KING

Dictionary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 31

CASSIE SPARKMAN

Two Poems . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 32

JOSHUA GUNN

Two Poems . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 36

MAGGIE SMITH

Two Poems . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 38

OLIVER RICE

Points of Interest between Monroe City and Slater . . . . . . .42

REBECCA HOOGS

Song from the Antarctic . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 44

JAMES . MCAULEY

Two Poems . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 45

NICOLE COOLEY

The Archive of the Future . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 46

POETRY NORTHWEST: SUMMER 2000

Tina Kelley

Five Poems

STRANGE THAT THERE ARE NO

Birds called the Glass Bird

Islands named Always

Mountains named Swift

Roses called Rhinestone.

I would buy a Beloved’s Breath Lily,

a cookie named A Kiss Before Sleeping.

I would visit that nursing home, Dismal Harmony,

and stop at Swaddling Towne rest stop.

There is no word for the way little girls run

when their hands are sticky, no type of snow

known as Dead Diamond, no Solace-Dropping

Tree or Defibrillation Symphony,

N0 infant son was ever christened Life Affirming,

though each one could be. There is no city named

Nimble, no Slenderest Street, no Toyota Lithe

or lipstick called Go Away.

There is a kind of crying I call Psalm 911, but no one else

does. There is a sleep

known locally as Severe Tire Damage; do avoid it.

The world may not be big enough for a dance called

Constance,

a church named Refreshment, a wind known by Refuge.

There are no planets named Polka

and it is too bad, really, and no clouds

called alizerine crimson. Darling, make me a crayon called

Shiny Calico Cat, and find our recipe for Birth of

Spring Cake.

For you, I would make the quilt called Every Soft Midnight

and fly to Only Ocean. I know there is a Marasmus bone,

named for the failure to thrive due to lack of touch. But

you know –

how to hold mine, in an embrace called Always Welcome.

THE KINSHIP OF HATCHLING AND SEEDLING

Because you can’t hear one of them alone, like snowgoose, like foxglove,

because they live in arpeggios like old squaw and fuchsia,

because they lilt under their own steam and stem, flinging petal peals of color,

I know that birds and flowers are identical.

I know that a green-winged teal is really a turquoise campion, with wings splayed back,

and a common golden eye is an ox-eye daisy, helium-filled, the string let go, gloriosa.

Name three differences between the horn of the horned lark and comets of columbine.

Perhaps early on there was a uniformed conductor, marking each with a chalk cipher,

telling each fast heart to stand in a Latinate line, dividing groundsels from ouzels,

sprit-tails from mist maidens, leaving a special spot for the rose rising above its whimbrels,

so duck-feather taut that a drop of dew forever remains a globe. The woodrush is first cousin

to the woodthrust (or swamp angel), kin to the celestial longspur, whose daughter,

the Lapland larkspur, keeps its wings wren-high. Is that a boreal limpkin near a shooting star

or an Alaska spring beauty on a roseate spoonbill? In all four, the inflorescence is elongate,

the pinions opposite and whorled. If it took a scholar to tell slender hawk from slender hawkweed,

in which kingdoms should we put the lady-of-the-waters and the silver tongue?

Who could tell them apart, the streak-breasted grass sparrows and sparrow-breasted streak grass,

who could divine if the blossom—billed coot is more blossom than bird? So to simplify matters,

some became rooted, in crotches of trees, wherever the dry moss and down dust settled in swirls,

and others flew, dipping and dallying at the pace of a roaming bee, high and safe over the soil.

“HE IS EVERYTHING EXCEPT OLD”

You are the iris blooming in my garden

that I didn’t know had been planted there.

You are the bubble in the carpenter’s level, rising.

My following sea, my thank—god-for—strangers,

you’ve become the one I call with good news.

You are as close to me as my sighs a month ago.

My brain is firing on all pinions; the gods are shining down on us.

I want to have secrets with you, want to carve your initials

in my journal, in my garden, my diet, my calendar.

Cancel the papers, screen all calls — may this be the birth of an anthem —

Drag out the snapshots, buy more bedclothes.

Avoid operating heavy machinery. Swaddle me in your stare.

Hit the pause button, fit more hours between these hours.

Send out the announcements, proclaiming the gospel

of the existence of new passion. Dear lord protect this love.

My tenderness towards you bleeds out like a dye

and extends to the other drivers, the joggers at the lake,

the salesman at the department store, the meter maid.

I want to have a famous love, one that journalists come

from states away to document, because we have made love at least

every day for forty years, perhaps, or because you told secrets

to my belly while I carried our child, or because you took the dog out

up at the cabin at 3 a.m. when it was 22 degrees and the fire had gone out,

or because you buried the cedar waxwing that rammed into our window.

If hearts, in cards, were black, not red

and if you were gone, if you had left,

the world would be too big without you.

RIFF ON RUMI

The stars don’t say, “How longdo I have to keep shining?” — Rumi

The hummingbird heart can’t count that fast, but beats its frenzy.

The skater’s—dream-that he—has forgotten-his-skates travels the world without asking directions.

The humpback whale, south towards Baja, never wonders what night songs are sung in cathedrals inland.

The free—floating flame doesn’t wish to land.

It soars, thousands of feet above, refusing to want a wick.

The raindrop doesn’t ask if it will fall on water or soil.

And the riverdrop prefers not to know the height of the cliff it slides over.

The cloud will run into a mountain or not. It doesn’t matter.

The sun couldn’t care less if the blue planet spins.

The yellowest poplar leaves have no idea how they galvanize the black-gray sky above them.

To run, the foot doesn’t need to know if the earth is solid or a skin of dirt in danger of collapsing, ready to take us to the empty center, where we could look through beneath the rest of the world.

The hundred-year house, held together by memories, chooses not to worry about the life expectancy of the last person‘ who remembers it.

So I will not ask the nature of my future.

Cognac has no way of knowing that its color also lives in the heartwood of trees.

The young woman doesn’t question the cruelty of what the old man knows:

The older you get, the more damn memories you have.

The 300-foot cedar doesn’t wonder why it lifts a ton of water daily, to add another ring.

Fire, however, is crucial to the forest.

The unmatched spoon does not feel lonely, even though the other three are across the country.

The revolving door does not wonder why it can never be slammed.

The dam does not visualize its deafening, inevitable crumbling.

The cartographer doesn’t ask whose hand really traces the shoreline.

And that thinnest membrane between laughing and crying is secure in the seven reasons for its existence.

HOW LOVING, IN LATE MIDDLE AGE, FORGETS THE SONG OF CAUTION

The not terribly recent blonde has a fast glamour to her,

like water drops falling off a freshly washed convertible.

She has a holy groin, pheromones that strike like lightning birds.

She makes men cry out for their ancestors, seeking mercy, loves how

they ease their charitable smoothness into her body, how they say

“I don’t want to not be kissing you,” how such sudden and early

lovemaking can still be a form of prayer. But everything

changed when she retired early to Las Vegas, or as she called

it, Lost Wages. Nothing changed in what she did,

displaying that otherworldly girl-talent of taking her bra off

from underneath her shirt through her sleeves, growing

so close, so soon, with each new lover that they were facing pages

in a shut book, dressing all her men in the colors of their eyes.

They put the leer in lyrical, and it was ogod, I mean good.

But one May, when Jerry was as close to her as a toothache,

trembling, arcing back, climbing the peaks of superlatives,

he died on her. Right on top of her. The police came, the wife

was called, the blonde was left with what noise is left

after a piano falls down forty flights of stairs. She saw a whole year

through a wince, studied how to live to be 100. She took up with

her high school sweetheart, who craved the hospice of her lap

after half a century, with half a lung left. So when he joined

the never after, right at the supreme moment, it did not yet

appear to be a trend. With Ernie, she dreamed of a wedding

in a butterfly garden, a honeymoon under the blaze of

Aurora australis, that moment when the front wheel rises up

and the rear wheels still speed along the runway. Elbows locked,

back arched, she looked down on him, but he was a thing,

a carousel horse, frozen but moving as the bed bounced to a stop.

He became her favorite among the dead. And night or wrong,

day or right, she found another, and another, old teddybears in heat.

You can’t slam a revolving door. She studied the difference between

shouting yes yes yes and no no no in the middle of the night.

How naked they looked, like a typo exposed, picked up out of the sentence

of her embrace. Once she told Lewis about the song she wanted to write,

hummed the first stanza for him, but he was gone, the song with him,

before the next morning. She was sued by his survivors, joined the sorority

of others whose partners had died on top, felt the tiny roots her lovers left,

torn out imperfectly, growing inside of her. As she fell ill, she vowed to find

her third husband, the one who had climbed McKinley and never came back,

daub his favorite, dusty cologne on her slack neck, and take him, take him

into her waning warmth, rise together to the mountain, and so very far beyond.

Thomas Brush

TEACHING

This all I have

Left, a scattering of poems drifting like waves

Of dust, thirty years

Deep, the ghosts of names gliding across pools

Of rainwater, leading to and from

School, essays that describe

What Hemingway might have danced

In Paris, 1925, fictions,

Of crushed hearts, of guilt and blame and innocence

That are always true, voices

That aren’t afraid

To cry

Out. The startling shapes and colors

Of hair and eyes, the storied

Touch of fingerprints impressed on every surface

Of the flesh of this room, scraps

Of dialogue on desks—Whoever erases this

erases meaning—I called, but no one answered-

(while outside waves of wind build toward a summer

washed clean as their dreams), the raining blooms

Of their breath, their anger, their laughter

Carved in the window sills, traced

In white-out, marking pens, murals

Of comic faces painted years ago.

And always,

When snow begins to fall, they rise,

Rush to the windows, carrying me

With their beautiful shouts, as if for the first

And last time in my life the sky

Comes apart again

With childish wonder,

With joy.

Kathleen Lynch

For Lynne KnightTORN BIRD

She slumps in the chair she can’t

wheel by herself, a blither

of trembles, mouth refusing

food. But her hand bolts

for the ice cream cuplet,

jabs, like a snake’s head

striking. I don’t want…

she can no longer stitch

a sentence together

but there is in her face

‘a torn bird, half raising

its wing to lift off, half

mumbling I ’m …mmnn

…let…let

I daub the corners

of her mouth, guide

the spoon.

Once she saw me

shivering in the shell of our house,

dirt floor holding hard

to the cold. Pass me mah fan,

she drawled in luscious

fake southern, Ah am just

swelterin’, Honey. Aren’t you?

Cocooned in the quilt with her

body beaming heat, I swear

I heard exotic birds,

fierce, exciting the jungle

canopy with their cries.

I fell asleep believing

I smelled honeysuckle.

Now everything is gone

but the ancient thumbprint

in her brain making her eat,

and breathe, breathe, the last

of her human words snagged

randomly on the thread

of that breath, breast

feathers blowing away.

Floyd Skloot

Three Poems

EVENING SONG

A flare of daylight sets my face ablaze

in its frame above her bed as the sun

sinks. Full Indian summer but these days

she is always cold, always wanting one

more layer of clothes or cup of hot tea,

grumbling as she hugs herself and paces.

She feels dark vapors in the air, traces

of dust. This is not where she wants to be.

When she sits, a shard of memory glows

and fades, the past an empty theater gone

dark the moment she arrives, curtain closed,

orchestra never launching into song.

For years she has been slowly going blind,

drawing the world into her corner room

beside the sea, drenched in endless gloom.

I am no longer in my mother’s mind.

POOLSIDE, 1961

There is less than one hour left

and my father does not know.

He lies there in faded light

green trunks, turned belly-up

beneath a livid sunlamp,

smoking down his last cigar

before the time comes

for him to rise and dress.

He loves the sheer arrogance

of such heat, its dragon’s

breath across his chest,

and he fills his lungs with it.

Minutes remain but still

he does not know. He thinks

of the long morning spent

riding bridle paths on a bay

gelding, the mid—day nap,

pinochle on a sun-drenched

patio and whiskey as clouds

turned his bright day dark

in the blink of an eye.

He thinks of tomorrow only

as a long drive home.

Seconds more as he rises

to stretch and blink salt

from his eyes. He does not

know yet. Without the least

thought of time winding down,

he tucks glasses in a towel

on the lounger and strides

across the deck as though

it were nothing. He breathes,

flexes his toes over the edge,

dives into the cool embrace

of deep water and dies.

O’CONNOR AT ANDALUSIA

“Sickness before death is a very appropriate thingand I think those

who don’t have it miss one of

Gods mercies.”

—from The Habit of Being, F lannery O’Connor

It came with the steady pace of dusk,

slow shadings in the distance, a sense of light

growing soft at the center of her body.

It came like evening to the farm

bearing silence and a promise of rest.

There was nothing to say it was there

till she found herself unable to move

and stillness settled its net over the bed.

A crimson disc of pain suddenly flushed

from her hips like a last flaring of sun.

She believed the time had come

to embrace this perfect weakness

that had no memory of strength,

a mercy even as darkness hardened

inside her joints. It was not to be

missed. Nor was the mercy of sight:

she believed the time had come

to measure every moment and map

the place she soon must leave.

At least she had been given time,

though her wish would have been

an hour more for each leaf visible

from her window, a day for trees,

a week for birds and month to savor

the voice of each friend who called.

Though she never belonged in the heart

of this world, she gave this world her heart.

Within her stillness she remembered

the first signs: that brilliant butterfly

rash on her face, a blink that lasted

for hours, the delicate embrace of sleep

veering as in a dream toward the grip

of death, hunger vanishing like hope.

Her body no longer knew her body as itself

but this too was a mercy. To leave herself

behind and then return was instructive.

To wax and wane, to live beyond

the body and know what that was like,

a gift from God, a mixed blessing shrouded

in the common cloth of loss. Half her life

she practiced death and resurrection.

Thom Schramm

POET ANONYMOUS

For the same reason I will not run

for President

I no longer rhyme: I can’t afford to.

They are expensive, those words that ring

my tocsin heart;

they cost me jobs selling watches and cars

plus commodity talk used to swing

deals in dark bars

in D.C. Put me up at the P.A.

and they accrue so much interest

the sounds don’t stop

until hawks pierce them with squawking nonsense

no sane caucus would ever elect.

So I’m caught here

in the eternal smear campaign of sound—

less my partner in crime (my vice echo)

to ride shotgun

as the hawks refuse the crumbs I throw.

Michael Cadnum

TIDE

What was amazing was

we wanted to go there, jumped

up and down when Dad said we could

pile into the car. The road stopped

where it washed away, jagged

green-haired slabs of

sidewalks, bad footing, rusted

monstrous engine parts.

Dad smoked Viceroys,

and now and then the thread

of tobacco would touch us

where we teetered among the suck holes

of sea anemones-and the cringing

crabs with their black, jointed legs,

cavities full of silent water

all the way to the waves

tearing themselves to pieces.

Among the concrete chunks

deep-fried with barnacles,

my sisters found mother-of-pearl

shards, sand dollars, one foot,

then another, almost falling, and I

found objects that had owned human

intent but had altered, spikes fat with rust,

bolts swelling from the inside

with corruption, while every sound

even our own shouted names,

vanished, one big lung holding all the air.

Susan Blackwell Ramsey

three poems

EMERSON’S EYES

[Emerson] now got his future exactly reversedwhen he said,

“You may perish out of your senses,

but not out of your memory or

imagination.”

-Robert D. Richardson

In the end, God cut Emerson a break.

That mind had been stoked nova-white for decades,

reading German philosophers, Hindu sacred texts

to light the meadow where Waldo wrestled with

the angel of existence, demanding meaning.

No one’s word was good enough for him.

And he lived. Any star can fill the sky,

then fall in on itself, demanding darkness,

die of consumption, the Hellespont, the head

in an oven. He mad his name, then kept on living

up to himself, refusing to relax.

His first wife died at nineteen, coughing blood.

His first son died at five. Death circled him

like buzzard on a thermal. He persisted

Finally God allowed that brain to slip

free from the limits of language, like

a watch spring from constrictions of its case.

The ideas stayed’ names went drifting off.

He started tying labels onto things:

an umbrella became “what the guest leaves behind.”

Look at the final photos, the portrait on

The Portable Emerson. The brow is there,

the eagle’s beak. Look closer, at the eyes.

As if through a backwards telescope

you see the nebula which was his mind

spiraling dreamily out into darkness.

BAR TRICKS OF THE OVEREDUCATED

These guys get nasty. Some nights it’s like watching

Hemingway bend a fork in his flexed arm,

throwing it on the table, challenging Hammett.

I’ve learned the warning signs: postmodernists

bear watching, Satre signals trouble. Kierkegaard

means grab the cash and dive behind the bar;

you’ll be combing slivers of contempt

out of your hair for days.

Once or twice in your life you’ll see it swing

the other way. At two beers Wayne agrees

to give ‘em either “The Shooting of Dan Magrew”

or Auden’s “Limestone.” With three he’ll alternate stanzas.

Paul’s singing “Rise Up 0 Frisian Blood and Boil”

in Frisian, with his feet turned nearly backwards.

As the applause dies down Kim takes the floor

demands silence, announces he’ll recite

pi to thirty decimal places. They start

pounding the tables when he passes twenty.

Backthumps and beer as Dave’s friends goad him up

drunk enough to do his Dylan Thomas,

sober enough to succeed. Di’s bellydancing

for a table singing “Stopping by Snowy Woods”

to the tune of “Hemando’s Hideaway.”

A smell of scorching means Rybicki’s turned

himself into a sheet of flame again

These guys are the Wallendas of tone. They know

it all depends on upping one another

without falling into ridicule

or dignity, piling delight on unsteady delight.

It’s a nine-man tightrope pyramid

paced over broken glass and rattlesnakes,

blindfolded, backwards. A sneer could bring it down.

On the other hand, hearing gasps, look up,

watch one lose his footing, lift his arms

and glide the last few yards onto the platform.

BACKSTAGE DUTY AT THE ]UNIOR CIVIC

These desperate outlaws, these corrupt officials

are so young they take stairs two at a time

for fun. The Sherif of Nottingham, a tall boy

with curly hair, not old enough to drive,

gives me a smile where I sit invisible, knitting.

He goes in to get his makeup done.

I know his mother’s dying, her skin, her organs

slowing turning to stone. He told my daughter

she cries and he doesn’t know what he should do.

The Makeup door’s propped open by a box,

battered and strapped with duct tape. Someone wrote

“Crash Box” on the side in Magic Marker.

‘A kid is curious. The makeup man

picks it up and lofts it underhand.

Landing, it sounds like the Apocalypse.

It sounds like the wreck of a stagecoach carrying

a galloping cargo of anvils and chandeliers.

It’s glorious. They nudge it back in place.

We’re brought up to be brave, and brave is silent.

We strangle on silence, but what words could we use?

Here’s noise commensurate with catastrophe.

I want one for myself, want one for Aaron,

for his mom, for everyone who knows

they’re cast in the big fight scene at the end,

have read the script and know that they will lose.

So that, stripped of costumes, we can climb

those last steps panting, heave our box and howl.

Jane Eklund

THUMBS

Without them, there’d be no incentive to stand upright,

what with everything we need so far removed

from our mouths. They’re the reason we’re on this end

of the can opener, this side of the steering wheel,

this edge of the water table. Ever since we figured out

how to pick things up, we’ve been picking up

everything, apples, pencils, remote controls. Hold

that thought. Or better yet, follow it

down the length of the shoulder to the forearm

to the wrist to the tip of that fat finger of greed.

Little seductress, she’s got her own pulse, her own phase

of the moon. See the way she holds that cigarette,

twirls the stem of the wine glass? That’s class,

that’s desire, that’s nosing your thumb

where it doesn’t belong, and where it doesn’t

belong is anywhere other than the palm.

Even so, she’s itchy, wants out of the pocket, wants

to shoplift the first shiny gizmo to come

along, wants a ride in a Mustang, a run

through curly locks, a tap dance across the top

of a table, preferably marble, preferably Louis XIV.

But here’s the rub: Without the palm, the thumb

is nothing, the equivalent of one

hand clapping, an actor bowing to an empty room,

again and again, while the audience stands

helpless outside the theatre, staring stupidly

at the door handles and at their eight forsaken fingers.

Lynn Domina

LOVE POEM RELYING ON AN ETHNOGRAPHER’S MYTH

Here is the word for snow

rising with a gust, one flake settling

onto a lower lip;

and here are the words for snow falling upon a hedge, distinguishing

each twig, snow coating a ledge

marked with the three-pronged prints of chickadees,

the triangle resting in birch branches,

caught in spruce;

the months, their proper nouns separating the last

flurries from the first,

the verb indicating a last snow melting early

into the seed, the arced stem, the yellow flash of crocus;

the difference between snow on Christmas and on Epiphany,

snow casting light onto a photographed facade

and a photograph of snow;

the forms of angels in a backyard, snow dancing

on the hooded heads of children;

the adjective applied to northern constellations obscured by snow

or snow obscured through steam

drifting from the moming’s first coffee

brought to you in bed

on a tray with marmalade and buttered toast.

Receive these words, this world

billowing, raucous, abundantly falling.

Harry Humes

Three Poems

ATHEORY

They have gathered this late afternoon

at the end of October, the swallows

Linnaeus thought slept

all winter beneath ice,

legs tucked up,

their glistening purple

and white covered with gravel.

The swallows circle

above the lake after bugs,

then dive to sip the water,

leaving behind circles that break

softly against the shore.

Why not at such a time

believe in them folding their wings

and slipping beneath the surface?

Why not let a season and its sadness

be dealt with simply as that,

with hardly a splash at all?

LATE NOVEMBER

Its front leg caught in a steel trap,

the raccoon had tom the ground with its struggle.

The trap’s drag hook was tangled in honeysuckle,

its branches shredded, bark scraped off.

The trap clinked in the dusk.

I lowered my coat over its head and shoulders.

It growled and rattled its teeth.

With one hand I pushed down on the coat,

and with the other forced a stick

between the trap’s jaws.

They opened just enough for the leg to pull loose,

the leg almost chewed through,

the leg from which hung shreds of skin and fur.

I pulled away the coat and the raccoon stumbled off,

stopping once to lick its damaged leg,

then splashed across the stream.

Blood swirled downstream.

Water dripped from belly fur.

What was it that found me after the raccoon vanished

into thick multiflora rose? A hand maybe,

or words pushing against my eyes,

maybe out of myself for a few minutes,

my mind like a failed theory.

Next to me, the white peels and splotches

of the sycamore rose into the sky.

Lower down, nothing had changed.

THE PORCH

This is the evening I have finished

the screened porch my father

always promised her.

He stole two-by—fours, nails,

a roll of screen from the Colliery,

but never had the time,

always whistling off around Sammy’s comer

and calling back to her,

Tomorrow you ’ll have the damned thing.

Out she comes,

dry dough under her fingernails,

slowing when she sees the porch,

her old round table, some books,

a View over the red barn

and up Kohler’s Hill.

She lays her hand flat against the screen.

She straightens her dress beneath her

and sits in the wicker chair.

She notices evening primrose

and the last celandine along the swale.

He would have done it, she says. He would.

William Greenway

A WOMAN BROUGHT TO CHILD

Sherry Greenway 1943-1999The second law is that the bad news is always

worse than the good news is good:

I won a prize,

and my only sister died.

She never had a chance.

I remember cowering while

our parents upstairs screamed

at each other again about her grades, until

she stood up, threw down her schoolbooks,

and began screaming too.

If anything happened, it happened

to her: nickname Stinky, coonskin cap

with the plastic pate stamped Davvy

Crockett, tonsils, appendix, wren

bones breaking, green eyes behind

batwing glasses, the boys

staying away. Algebra

chased her from nursing school

like nausea, then a brick Bible

college, a redneck marriage, and losing

her babies to the county.

Barmaid, she was trying

to start again when I left her

drunk on the doorstep that

Christmas ten years ago, gave me that old

picture of her as Shirley Temple with

a cowboy hat, white taps, red

sequined cuffs that swayed to “Pony Girl.”

Her new man stayed inside with his

cartoons and vodka in that month’s

dump, as she said goodbye

for the last time, hugged her new

daughter, wept, and waved.

You know the story—it’s the one

the private eye tells about finding

the guilty, who done in the floating

body of the woman with no last name,

the first something rich, like Candy

or Ginger, who somehow got lost

and fell in with bad companions.

Somewhere near the end of the movie,

the gumshoe finally tracks the fictional family

down and shows them the picture

of the woman they hardly recognize, yellow

and withered, and they show him the picture

of the little girl they remember——

squinting into the sun, standing

in the doorway to the rest of her life, waving

goodbye, her jelly bread falling

jelly side down.

Julie Larios

WHAT I IMAGINE WHILE RIDING THE FERRY

That all the sharp instruments are ready:

that he splits you at the sternum

that he spreads your ribs apart

that your body steams in the cold air

that he notices me in the room

and pauses

that he puts the knife down

that he comes to me easily

the way saltwater would come

to a river mouth — licking

and lapping at the angle of repose

that he turns to you again

touches each rib, talks

into the tape recorder

lifts the small saw

that he hesitates

that he hesitates

that his decision is arbitrary

that his decision is tidal and lunar

that he looks toward me

that he closes you

back into your body

as a father closes the coat

a child against bad weather

that he leans down over you

that where his lips touch

they leave no scar

but leave a stain

that the stain spreads

wavelike and the wave

becomes a heartbeat

that he’s gone

and his tools gone with him

that you stand again

that you haven’t ridden in the boat

that you come toward me easily

like saltwater to a river mouth.

Jill E. Thomas

ELEMENTAL

In the garden, things that make no sense

continue to make no sense.

I am there at dusk, a full moon rising

to my left, a full sun setting to my right,

watering the earth and imagining

my importance.

I like to watch the puddle grow between strawberry

patches, to pull back the silver—green leaves

of cauliflower and find the white vegetable blossoms.

When no one’s looking, I water the weeds.

They’re thirsty too. My god is a drought

because I’d rather love plant life to corn height

and wheat profit than kneel in dark cathedrals.

I can’t forget that I like the echo of those vaults,

the way stained—glass plays with light,

and even the painful silence of prayer, but out here,

there is a vaulted blue or falling gray and even silence is not

so silent: the hose is a healthy avalanche,

and ants cause earthquakes.

I could stare at compost for hours, watch it composing .

symphonies of earth-life from bits of browned food, weeds,

waste, But when does the change happen?

Maybe if I watch long enough, wet the shrinking mound

each day, I’ll see the molecular action. It reminds

me of trying to catch my bones

growing at ten while I should have been sleeping.

Here, compost gets smaller; it does not calcify itself,

But builds by shrinking into one heaving life.

I wish we could take things back to the molecular

level, take back the free-

way, the empty carpool lanes, the acres of parking

lots and be like mud: compact, nourished, stronger

when smaller, respected in age when the archaeologist

digs through the sediment instead of paving a new sheen.

Maybe that’s why I love mud: stepping in it, slinging the slosh,

feeling it dry tight under my nails because it’s rubbing

the past into me knowing the future sprouts here too.

Maybe it’s like the name that woke me up, the name

I gave to my small house plant, as if in naming it, I call

it mine and take responsibility for its water. August:

everything warm, orange, austere, wise to live but soon to die.

The name was like a challenge from my dead grandfather,

whose middle name was also that summer month, a challenge

to let life happen while I watched. But I’d like to be a part

of it all —— the future history and present misery.

So please, when I die, forget the casket, don’t bother with ashes.

Let me compose compost, my greatest creation,

like writing in mud.

I could start now, before death: next week I’ll put my fingernail

clippings and all the hair from my comb in the bin.

In a few months, maybe a year — only the worms know — dead parts

of me will live again, will plant and let plant,

and if I’m lucky enough, maybe green will

push through the asphalt and ask me for water.

Kenneth King

DICTIONARY

The dictionary one lover sends to another

Words of her language printed in bold

Interpreted for him in quick-take snippets

Hints on placement of tongue and lip

Pursings and sibilants, fricatives and gutturals

There is so much the loved one needs to learn

And unlearn—each foreign to the other at first

Each learning the life-taught language of the other

The words for breathing, food, and arousal

Habits of native country the town

She grew up in the book she sends

Small enough for hand

Still’ the miles of ocean between them

Fragile language of the heart the only

True interpret

Cassie Sparkman

Two Poems

IF ANYONE IS KEEPING TRACK

This will go down on my list of sins:

running after you down alley after alley

while a sobbing shuddering woman

pulled stocking up, felt

for what the man had stolen,

hands moving across her back,

under her skirt.

I will dream of this always:

us walking home,

arm hooked into you, laughing,

then that noise

in the first alley on our street,

glimpse of a woman

on pavement-made-bed,

struggling

whimpering

man on top,

passing, then

you turning,

me tugging,

you tearing

from the warm circle

we cast into the cold night,

him

turning towards our tearing-tuming-towards,

the noise we make as he

runs bag in hand zipper tugging up

sticky fingers,

the noise she makes

standing up

as he runs,

cold rushing in

as he runs

and you run

and I

scream

then run

and she

cries.

Searches hands under her skirt,

looking for what was stolen.

This will go down on my list of sins:

how the sight of wool coat flying behind you,

your hair casting erratic halo-shadows

into puddles of hazy light,

my body straining to keep up,

were for minutes my life’s breath.

The woman’s sobs echoing,

begging: help, anyone.

Me running after you, cold, believing

if my eyes didn’t hold you however distant,

my voice not constant siren sound,

then my arms would never again

fold your warmth into stomach,

around heart.

I will dream of this always:

my screaming —

running after you

down dark alleys where dumpsters

yawn colored mouths, swallow

your name and my voice choking on it ——

the cold bouncing a woman’s sobs

off my guilty breath ——

No one charging to our rescue.

You —

Him —

Vanished.

If anyone is keeping track,

this will go down on my list of sins:

my screaming for you,

my selfish heart,

when I should have been screaming

for her.

EVERYTHING, ANYTHING, NOTHING

We are thinking of

everything and nothing

at the same time because

anything could happen

and does.

I guess you think you gonna

wake up one morning and find me gone.

You think you gonna wake up one morning,

A reach a search party of fingers

across the mattress,

have to label me missing

from the caverns I’ve built in your chest.

You think you are gonna wake

and find me there

but not, my eyes vacant,

lips kissing without touching you,

my words gone to ash

before breathed.

I guess you think you gonna wake up one morning,

find you are weight—less, anchor-less, hollowed-

out.

I guess I am thinking I’m gonna wake up

one morning, turn, and hit a brick wall,

your back. I’m thinking I’m gonna

wake up, starving from dreams,

find an Oklahoma of space between us,

my hunger a keening wind

that dies out before touching you.

I think I am gonna wake, find you

frantic with a job you hate, laundry, jogging,

dreding your hair to another scalp,

tying up new love.

I guess I think I’m gonna wake up one morning,

find myself cast off, sinking, heavy

with love you have

left.

I guess we are thinking

of everything and nothing

at the same time.

Everything: mornings

mile-markers on a road

where danger sleeps

inside each curve, and we

are evasive.

Nothing:

the breath we share,

natural as skin.

We are thinking of

everything and nothing

at the same time

because

anything could happen

and does.

Joshua Gunn

Two Poems

THE SEAHORSE BAZAAR

People gather at the wide-mouthed

jars filled with tapered heads,

bleached abdomens and tangled,

comma—shaped tails. One complete

husk, finely crushed, is said

to deliver sexual potency enough

to boil the self into an invisible gas,

filling the atmosphere of one’s lover.

The difficulty is finding one intact

among this hurried whiteness and

confusion of female parts

pressing into male parts. The impatient

buyers haggle over length and width,

the curl of head sections and broken

tail sections

until someone spots one, a male,

and whole. The crowd appreciates

the slender head, its easy convergence

into a singular tip, like the brush

of a pointillist. The torso,

with its chalky, ceramic overlay, its kiln-fired lattice

suggests knuckle bone,

rib bone, the human form turned outwards

and reversed. They scrutinize the stomach

pouch of the male, with its black wisp of birth hole

bulging with newborns in

unhatched thousands.

The moneyed buyers push their way to the front.

The seller holds up the seahorse

and shakes it over the crowd. Calcified ghosts,

in their hurry to fill all transparent space,

rattle in the womb. Everyone looks up

with his porcelain face.

THE NIGHT GARDENER

Here is the body sleeping. The slender

hull filling and emptying. Here,

rain on the roof. Beneath it,

the window, the chair, the bed.

Then, the pattern

of the body, its shape and

form pinned to the outer dermis

of the night, the cold, the stillness.

Muddy tulips. A sliver of moon.

Here is the shape

the small of the back assumes.

Insinuation of color,

of knees, sinking.

Here is the color

occupying the narcissus, the petal,

the leaf, the root. Here, the form

kneeling, form

of the hands, like a film

of dirty ice in the foreground.

The body sleeps inside.

The head, the knee, the hand.

Outside, the figure in the garden,

the air, the stem displaced,

the head-shaped outline, lifting.

Maggie Smith

Two Poems

FOR DOUBTING THOMAS

I was tired of the smoke

and mirrors. The loaves, the fish,

but not enough time.

Not nearly enough time.

What could I say to him, friend I buried,

when he woke and called to me

softly from the shadows.

G0 now. The business of faith bores me.

I could take it or leave it.

Understand, I touched his wounds

because I wanted to feel

his ‘warmth on my own hands.

If I doubted anything then,

it was humanity.

Disillusionment

is what happens when men

dabble in magic.

Celebrity is a tree on fire

and of the thousands standing near,

none is near enough

to lick the flames from your face.

Once the embers burning

above us were enough. I believe

he doubled back from death

to breathe home’s balmy air,

to simply stand in light

among us, gaping one last

time beneath the high heavens.

For this brotherhood

I lose a brother; I spit

upon the lot we’ve drawn.

So much for twilight spent floating

on the river, talking of women

we were not to love, and of their skin

scrubbed sweet as tangerines.

So much for nights passed

in the desert, drunk under the young

stars whose names were new. Once

my friend agreed: No one

could recognize each luminous body

across this broadening,

eternal cleft.

MEMOIR, IN CIRCLES

There is a sense of touch

transcending the fundamental

distinction: here, there.

I am paraphrasing myself here.

There is no such thing as an open

circle. We curl in, touching foreheads,

creating a closed circuit, inadvertently

falling asleep. His subsequent dreamlessness,

a sky cast over.

I am more out than the stars. My view

from the plane is that of one

traveling alone. Look

at the constellations now, noting

how the lines have changed over time.

We recall them differently than they are.

Any point set on the circumference

of a circle could be called the beginning,

the middle, the end.

Old English version: This is weird.

I don’t want my life back. My thumb,

small with the nail chewed to the quick,

is the same as his but scaled down

exactly one size. Modern translation:

This is fate. Peas still in the pod.

A green taste, reminiscent of cool water.

I’m wondering now if it was even

my suitcase I lived out of all week, folding

and unfolding. Where do I expect

to find myself in all of these words

kept at room temperature. I have unleamed

the water from him by floating

on my back. Vertigo: The sixth sense,

we assume, if five is still touch.

He suspended me in the warm green

surface of the lake, his right

hand cupping the back of my head,

his left at the base of my spine.

My heart was light

in my chest, keeping me afloat.

A column of clouds; a banister without stairs.

Think light: A blue freckled bird’s egg.

Think soft: Stepping out into the rain.

His grandmother is dead. Send the pale

roses with the pretty pink tips.

Meaning: Sympathy is inaccurate.

A name is not a name.

Helen-uh, never Helay-nuh.

We took our grief to the fireworks and sprawled

on the lawn with it, beneath weeping

willows of golden ash.

It was Independence day. From now on.

Until then I hadn’t noticed. There is a point

where even the clouds stop, exclaiming

“the sky, the limit!” Distance

that is mathematically sound.

My grandfather is dying. Turn your head

when you are floating

and put your ear to the water.

Listen. It sounds like a womb.

The body is your own.

You either reconcile it or it takes you,

frame by frame. Reconsider

that night the sun left without us;

we stood in the clearing looking out

as if the ship we had meant to board

had set sail.

We stood in the grainy darkness

watching the happened

sky. Becoming part of.

There is no such thing as an open

circle, or time, a closed circuit

that if blown could heal us to pieces.

Our books kept falling open

to the same scenes: A clear lack

of skyscrapers, a column of clouds.

The airplane windows, in my dream,

went blank as sheets of paper.

Then I woke. From now on.

A green taste, reminiscent of cool water.

There is a sense of touch.

Oliver Rice

POINTS OF INTEREST

BETWEEN MONROE CITY AND SLATER

There, into the green hills,

there, along the curve of the river road,

you can feel the old lay of the land.

•

Here is a house

that has given up to whatever will be.

People are in there.

•

The ages of the women,

a rowboat in the grass —

things look the same but are not.

•

You cannot explain these deft hands,

these childhood skies,

these unfinished conversations,

this face at the south window,

nor why they belong to the same place.

•

You understand the consolation

of these arching maples

on an ordinary afternoon

in utter reality.

Of a simple machine.

Soft words.

A thing seen coming from far off.

•

In the distance between them

are huckleberries in August,

is a silence that is not silent,

are pages in the cousin’s diary.

•

Seemingly at random

among the wild rye, the Vesper sparrows,

discarded moments lie where they fell.

•

They have a language

for a fence line,

an afternoon breeze,

a stripling becoming a tree,

the past arriving,

intimations of a journey,

but they cannot tell you what you want to know.

•

The thought stretches from spring to fall,

fall to spring,

seed clouds fly on the wind,

again and again

the fir trees, the fog practice to be what they are,

the young father watches his father,

again and again

the blackbirds make their nests in the reeds.

Rebecca Hoogs

SONG FROM THE ANTARCTIC

The day you were to be saved

dawns at sixty below. The sky

ices over, solid with cold.

You are left to finger the hot spot

in your breast, the place where

the cancer taps its ash. Above

this wildfire, your hand

is a slow satellite, each finger

an expert on you. Of second opinions,

you have ten. Of a way out, none

for now. You have x-rays

of a marriage glowing bony;

cracks threaded blue; biopsies

and test tubes. Perhaps it was

something you swallowed. A baby

tooth, snow pinched to a pea, all

of the pushpins on the map. Maybe

you gave the cancer something

to work with, work around and now

it rubs its twigs together, spins a fire

to whisk across your dry tundra,

to thaw the earth you thought too bare,

too cold, to burn ever again.

James J. McAuley

Two Poems

VIRTUAL CHESS

Castle the king and leave the queen exposed

To the knight who climbs like a spider on the file

Marked E. The plot’s fashionable for these vile

Fin—de-siécle politics, now composed

By the megabyte with lowly ones and zeros

Zapped through microchips with the effete style

Of a lizard snatching a gnat with its tongue while

Voice—Over preaches Darwin and the camera rolls.

Press Exit. Press Reset. Press Resume.

After the long ride west from the Caucasus,

Your captive, now your mentor, introduces

The older game: across the board there’s room

For the knights to take turns straddling the queen,

Bishops to bugger each other, the king to fondle a pawn.

IRIS

Not how you would be thought of, your color

Being grey, silky, fitted like a second skin,

Your hair flecked with it. Now, hearing your way

Of saying iridescent while I read your poem

Three years after your death, I am compelled

To check you out in Ovid, Lampriere, Bulfin, then

A book of flowers, where you’re discovered

On marshy ground, not grey exactly—in fact

A pretty blue-grey, a quiet type, a green cowl

To shelter the thoughtful inclined head.

.Not at all

The bright-winged messenger who’d drown the world

If ]uno put you up to it, but a quiet sylph,

Who could color the import of her message with a sly

Tilt of the head, those grey eyes steady, lips

Pursed, making a pretense of kissing. You could supply

So many ambiguities—gradations and streaks and tones

Of grey, green, blue—that for twenty years I saw

Rainbow, rainbow, rainbow where the sky

Lay on the wintry hills, weighed down with tears

Mnemosyne allows for you: flower, messenger, poet.

Nicole Cooley

THE ARCHIVE OF THE FUTURE

1. Egg—and-Glass

predicts the future, all girls know.

Here is how we choose our husbands:

crack the egg against the edge

of the looking glass, spill the white over the mirror.

You’ll see your future husband’s face.

Or the shape of a coffin. Or the body .

of a woman whose glance can kill a man,

curdle milk inside a cow,

turn churned butter into a sheet of wool.

2. The Body of the Accused Bridget Bishop is Due to be Examined

by the Magistrate of Salem Village at 6 o’clock in the Meeting

House on the Communion Table

The goodwives of Salem Village whisper what their husbands told:

She pinched. She bit

till a bruise blossomed beneath his skin,

purple petals spread up to the sky like fingers.

3. Marriage

In bed in the motel we stop spinning to remember.

The last night before I left

I climbed on top of you as if I could weigh you down

with my own body,

as if my hands were stones pressing you into the ground.

My breath stopped.

My throat choked.

I wanted to prove to you that I’d come back.

In the archive, in the bottom of a box

I find the goodwife and man

side by side in miniature,

painted into a frame

the size of a child’s hand.

The past comes back.

The pages of the book open on the table.

Memory is a warning, a winding sheet

the woman in the doorway drops

to show her body to the man

as their future breaks across the glass.