By Diana Khoi Nguyen | Contributing Writer

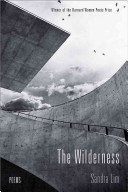

Sandra Lim is the author of two collections of poetry, Loveliest Grotesque (Kore, 2006) and The Wilderness (W.W. Norton, 2014), winner of the 2013 Barnard Women Poets Prize, selected by Louise Glück. Her work is also included in the anthologies Gurlesque (Saturnalia, 2010), The Racial Imaginary (Fence, 2015), and Among Margins: An Anthology on Aesthetics (Ricochet, 2015). She has received fellowships from the MacDowell Colony, the Vermont Studio Center, and the Getty Research Institute. A recipient of a 2015 Pushcart Prize, her work has appeared widely in journals such as Literary Imagination, Columbia Poetry Review, Guernica, and The Volta.

I read that you often return to Sappho, Wallace Stevens, Frank O’Hara, James Schuyler, Sylvia Plath, Anne Carson, Emily Dickinson, Ezra Pound (what an incredible list) and that you also read a lot of fiction (as do I!). Who were your earliest writing crushes?

Early in my reading life, I was very taken with 19th-century British women writers: Jane Austen, the Brontë sisters, George Eliot. I was probably more enthralled by the narratives than anything else at the time (though, I do remember thinking that reading Wuthering Heights was like breathing cold air), but looking back, I think I was also very interested in the movement of the (female) inner life in these stories.

My earliest poetry crushes include Sylvia Plath and Anne Carson—their intensity and control were / are thrilling to me. Here were poems coming out of desire, sexuality, anger, dream, pain, clarities of seeing and of feeling, the pleasures of risk and of enthusiasms—these things still surprise and inspire me.

As they should (and do for me as well). I can’t hear Wuthering Heights without immediately hearing and visualizing Kate Bush’s “Wuthering Heights”—she is someone who also contains a rich (female) inner life—who, like Plath and Carson, surprises and inspires me as well. Speaking of inspiration, I noticed that you have a quote from Badlands in your latest book and in one interview, you mention another Terrence Malick film, Days of Heaven. I hope you don’t mind indulging me here—Malick is one of my favorite filmmakers—how can I not be lured into and moved by his films’ lush, minimal-dialogue, and impressionistic qualities? Is Malick an influence in your thinking and poetics? What are some of your favorite Malick scenes?

Not an indulgence at all! I love discussing Malick, though I’m no film expert and completely take in his films on such an intuitive level that I don’t feel sufficiently articulate about them. But yes, some of his work definitely hovered over The Wilderness; or I should say, some of the ideas and feelings in the book rhymed with or otherwise came out of a certain tone that I think his films provided.

Some favorite scenes include the following: the famous one of Sissy Spacek and Martin Sheen dancing in the woods to “Love is Strange” in Badlands; also the scene where Spacek looks at images in the stereopticon and wonders about the man she’s going to marry; the final scene in Days of Heaven—“Maybe she’d meet up with a character”; all the scenes of twilight in Days are tender, savage, wonderful. The lightning storm at sundown in The New World; the scene where princess Pocahontas shows up to the English court in Jacobean dress, that ruff collar! Many scenes in The New World made me realize—not necessarily unhappily—how sad I was at the time of viewing it; that movie has a secret of scale that is disquieting.

Those are incredible scenes. The New World informs me in ways of seeing—did you know that for that film, Malick only used natural lighting? Which makes that scene with Pocahontas’ emergence in court in that dress with the huge collar both striking and stifling—I think the only light source came from window slits in that drafts, cold English hall.

As a fellow Californian, I imagine Iowa must have been like entering into a ‘new world’. What was your MFA like there?

I really enjoyed my time at Iowa. It was definitely a suspended period. I was sort of amazed to be in this very specific world, surrounded by people so bonkers and earnest about writing and reading and even treating their very lives as art projects, art material. The sense of determination in the air was tremendous; it was good to be in that. It was a gift to be left to one’s writing, even to one’s stretches of boredom, and to have all of it taken so seriously. With any MFA program, I imagine the community itself is so important to the development and nourishment of a writer. I also liked being in a smaller town for a time, though it was good to know that it was a limited amount of time.

I feel the same way: I’ve enjoyed my time in Lewisburg, PA, but think I enjoy it because I know my time here is for a set amount of time. I think being left to one’s boredom is underrated—especially since I feel no one permits him/herself that experience anymore (what, with all the smartphones, etc.). There’s something to be valued and gleaned from sitting on a bench (etc.), “bored.” Did you do anything in particular during these stretches of boredom? Any strolls through cornfields?

I completely agree with you—there’s so much pressure to always be doing something, something “productive.” It actually produces a lot of anxiety. While in Iowa, I took myself on walks, watched movies at the movie theater, went to a lot more small music concerts, and actually, I also went to a ton of plays there because it was affordable, so easy to get to the venue, and I felt like I had the time. That was really fun.

But you know what was really great? And I felt as if there was room for this at Iowa: hanging out for hours and hours and talking with friends at the bar or a café or at somebody’s apartment—sometimes we would talk shop, of course, but it wasn’t only that. There’s a scene in a short story by Katherine Heiny I just read, it’s called “The Dive Bar,” which sums up the kind of talk I’m thinking about: “Sasha does not know what this kind of conversation is called. It is not small talk, and it is not gossip precisely, nor is it deep and meaningful discussion. Dialogue, meeting, palaver, visit—none of them seem quite right. If there is a term, Sasha is unaware of it. She only knows she never wants to be without it in her life. Never, never, never.” I felt such recognition when I read that.

Did you have any time between pursuing your various academic degrees? If so, what did you do during this time?

I took a year off after graduating from college. I was trying to figure out what I wanted to do while working various temp jobs, doing a bit of freelance writing and editing, basically worrying my head off.

When did you know you wanted to get a PhD? Would you recommend emerging poets to pursue a PhD?

At first, I just wanted to have a few more years to read (and avoid law school). I felt as if I was finally starting to read with more astuteness in my junior and senior years of college. At the same time, I didn’t particularly want to be in an MFA program right then; something about the PhD seemed more logical for me at that time.

As for recommending the pursuit of the degree, it very much depends on the individual’s situation. Of course you don’t need a PhD to write poetry. And practically speaking, it’s hard to get a teaching job afterwards, as everyone who’s come through it despairingly knows, and it takes a long time to get the degree in the first place. It just depends on what you want to get out of it, what you can afford, in all senses of that word.

In the end, I actually got my MFA after I finished up my PhD in English, and for me that was a great way to do things: I loved that I had had time to read widely, and then suddenly I had two years just to write poetry (and to read more of course!). In terms of timing, I just thought I would probably not go for an MFA later, once I was caught up in something else, so it just seemed the right moment and circumstance to give myself the gift of time—two years to be in a writing program. But no one should go into debt for either of these degrees!

But the sequence of all this school—it was nowhere near planned that way when I first applied to PhD programs. I was also always working various jobs while in graduate school at Cal, so the idea of working at a non-scholarly, or non-teaching day job while writing was never far from my mind.

I know too well about avoiding law school (though I think my parents are still hoping I’ll do it one of these days). And yes, no one should go into debt for these degrees. Were you able to write much poetry during your PhD studies? When did you know you wanted to be a teacher?

When I started my PhD program, I thought about being a teacher, but there was no burning desire to teach in the beginning—I was still very much in perpetual student mode. Truly, I was still pretty lost. So at the start, I was just writing poetry “on the side” as it were, and taking workshops here and there. But my cohort was very special: in my class we had many aspiring poets, fiction writers, playwrights, musicians. I think we were all making art alongside our coursework when we found or made the time for it. I marvel when I look back at our class now—my good friend Asali Solomon just published her first novel (we attended Iowa together after Berkeley); cohorts Julia Cho and Young Jean Lee are renown playwrights; Drew Daniel is a scholar and professor of early modern literature, but also one half of the famous electronic duo Matmos.

That is an incredible cohort! Such diversity and talent—what a dream.

Your book, Loveliest Grotesque, won the Kore Press First Book Prize in 2006. Did a lot of time pass between your graduating from Iowa and winning this prize? Does Loveliest Grotesque resemble your MFA thesis in any way?

I graduated from Iowa in 2004, so I guess it took about two years of sending the manuscript out to contests before Kore picked it up. Loveliest Grotesque very much resembles my MFA thesis, although it’s thinner than the thesis, and I hope more refined.

While I haven’t read your MFA thesis, I certainly find it to be refined—and also feral in this wonderful, impactful way. It’s been about 4 years since I finished my MFA and I’m only now learning how to whittle / thin out a body of work. It’s terrifying and thrilling at the same time, like carving a sculpture (except with an undo option).

I see that you’re one of the faculty members for this summer’s Kundiman Retreat, a retreat that “hopes to provide a safe and instructive environment that identifies and addresses the unique challenges faced by emerging Asian American writers.” Do you feel that you have had to face any challenges as a writer of Asian descent? If so, do you mind sharing those challenges with me?

I am so excited to be part of the Kundiman community this summer. I know the experience will be as much an education for me as for my students.

When my first book came out, and I started to give readings for it, I was always (perhaps naïvely) surprised by how consistently I got asked about my subject matter, my themes, my content—basically, why weren’t there more legible markers or narratives of my racial and ethnic background, etc.? It made me feel a bit on the defensive, but down the line, I also didn’t want to be seen as writing out of the flip-side of this thematic-content model—that in not having much overt racial legibility in my poems, I was somehow purporting to write out of a “universal” mode of some sort. On both sides it seemed as if my poetic subjectivity was being circumscribed by a certain decipherable racial subjectivity imposed on me from without.

Poetry always alerts me to the solitariness of individual consciousness, to the mystery of other people with other subjectivities, and to the conditions and dilemmas of moving through private and public forms of life. Perhaps being a writer of Asian descent makes negotiating those public forms more vivid, to be sure. A challenge for every writer, I imagine, is to understand that real exploration involves real risk; it can be scary and exhilarating even to discover unexpected aspects of one’s own sensibility in writing a poem.

It certainly is scary and exhilarating. I hope to never stop discovering when I write a poem. Thank you for sharing your experience and thoughtful perspective on this. Kundiman is very lucky to have you on board this summer—I wish I could be there to learn further from you.

If you could talk to a younger Sandra, say, Sandra in her mid-20s, what would you tell her?

I’d tell her to look around and take in how beautiful her life was in mid-20s mode, that there was nothing really so bad about it. I would tell her to calm down, to take it a little more easy. But she wouldn’t have listened.

Do you have any advice to young writers who are struggling now?

Be unwavering in your dedication to make art, keep choosing it, stay passionate and ambitious! I still don’t know anything better than writing poetry. But I would also say don’t be afraid to become moderated by life. Not in the sense of diminishment exactly, but in the sense of being exercised more fully by it somehow. I say this because in the past, I often felt a victim of my own overweening will when it came to writing. I think now I was unknowingly putting up a wall between writing and life—some of this, a natural impulse to master or control life through art. But I’m now more interested in letting whatever makes up my life have its authentic say; I trust it more.

—

A native of California, Diana Khoi Nguyen is the current Roth Resident in poetry at Bucknell University and a 2015 Bread Loaf Bakeless Camargo Fellow. Her poems and reviews appear in Poetry, Gulf Coast, Kenyon Review Online, West Branch, Lana Turner, and elsewhere. This fall, she will enter into the creative writing PhD at the University of Denver. www.dianakhoinguyen.