by Bryce Emley | Contributing Writer

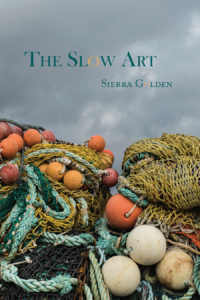

The Slow Art

Sierra Golden

Bear Star Press, 2018

Skippers and tide rips, sculpin and hagfish, bowlines and seines and “the faint sound of oars”—the poems in Sierra Golden’s debut collection, The Slow Art, explore a world most of us only see caricatured in movies and reality TV. Set in dockyards, smoke-stained bars in dying towns, and the perpetual dampness of the Pacific Northwest, these poems combine the language of the industrialized sea with colloquial familiarity.

One might imagine these poems sounding contrived in another poet’s work, but the authenticity of Golden’s poetry is rooted in her time working on her father’s commercial fishing boat, a period of over a decade when she might come home from her job and remark, “Haven’t been on land in weeks— / it seems everything could knock / me over.” “Appetite,” the book’s opener, shows us how the weight of such work brings daily life’s casual movements into stronger focus, and that each carries the potential for fleeting pleasures:

I find the exact wood screws

I need in the hardware store.

There’s fresh water, hot showers,

clothes warm from the dryer,

a bar full of strangers, cell

service, and this berry patch

where feral plants have blossomed

and bear tiny chartreuse fruit.

By honing in on these moments in the context of work, we can see their price, the little sacrifices most of us make thoughtlessly as we allow the things we do for money to pull us away from the people and places we care for most. In “Town Day,” a sailor-in-love comes to land and heads to the city dump, “the only place with cell service,” so he can phone his beloved among the “eldritch calls of ravens / scavenging bones and beer cans.” Efforts like that sailor’s show us what it takes to bridge the distances between us, to cultivate intimacy wherever we can: in boxes of unsent love letters, in fleeting conversations in bars, or while watching the lights of distant ships over the day’s first cup of coffee at three in the morning with Leonard Cohen playing to the ocean.

Golden concedes, however, that such distances can be much greater for some people than others. In “Gracias,” the speaker watches cannery workers “off-load sixty tons of herring” in the cold, leaving her to remark on the relativity of her own isolation, “I wish . . . that I never have to leave here, never / have to weave a home in some far-flung place, / dreaming my family together while / I work a job no one wants.” In a country where we’re promised opportunity abounds for anyone willing to work for it, but where many of those opportunities aren’t available to everyone living within its borders, work is as innately political as it is social.

But while it’s easy to see these blue-collar settings as an easy aesthetic or thematic categorization, to distill one’s understanding of this book down to just the “work” aspect of it is to miss the point, to see the setting as the subject. Golden considers her book’s working-class people and rustic, often unforgiving landscapes as opportunities for exploring broad human tensions: between struggle and comfort, between love and longing, between nostalgia and departure.

Tensions like these are intrinsic to our human presence in the wild, where Golden finds a balance between intensity and delicacy. In “Pleasure,” the speaker picks salmonberries and imagines being found by a bear and considers not danger, but “[h]ow strange it would be to know / he could devour a small stag // after watching his pink tongue stretch / and curl around a tiny red berry in the rain.” Even the most lethal predators seek out sweetness, like any of us, as Golden sums up in the closing line of “Playboy,” “Don’t we all burn to be touched?”

That desire echoes throughout The Slow Art as gritty narratives of hard lives ground the book’s more delicate explorations of relationships. Those two conflicting registers continually push against each other in these poems, fortifying by their friction the way “love knots pull tighter under pressure, stronger / than the lines used to tie them” (“Net Work”). Images of various knots, a fisher’s most essential tool, aptly appear as breaks around each of the book’s three sections, reminding us that our interior and exterior worlds—the efforts of our bodies and the desires of our hearts—are set against each other but become more singular the tighter they pull, that this is a necessary friction.

Whatever jobs we work and wherever we come from, The Slow Art helps us see how our bodies are the price we pay for our ambitions, our love, our living. Golden’s poems of jobs, home, and nature show that in our work, in our origins, and in the world around us we can see ourselves. The nature of our work doesn’t define us, but how we afford our desires is as necessary as the desires themselves.

—

Bryce Emley is the author of the prose chapbooks A Brief Family History of Drowning (winner of the 2018 Sonder Press Chapbook Prize) and Smoke and Glass (Folded Word, 2018). He works in marketing at the University of New Mexico Press and is Poetry Editor of Raleigh Review. Read more at bryceemley.com.