by Michele Sharpe | Contributing Writer

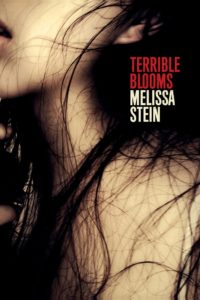

Terrible Blooms

Terrible Blooms

Melissa Stein

Copper Canyon Press, 2018

Melissa Stein’s second full length collection of poetry, Terrible Blooms, is a thriller: a family-dynamics and romance mystery with shifting voices, recurring landscapes, and gorgeous images that illuminate brutal complexities of the relationships we are born into, and those we choose. In these poems, immersion in suffering is inevitable, as are questions of how to thrive after suffering.

Throughout, the poems’ mysteries revolve around paradox, echoing the title’s pairing of “terrible” with “blooms.” Hate and love coexist along with praise and punishment, and sometimes the speakers of these poems can’t tell the difference. How is it that those we love so much can be so unloving, and how do we, in turn, punish those we love?

“Racetrack,” the poem containing the book’s title image, begins with a paradox, centers a paradox, and ends the same:

Velvet and shit: I summoned it

and come it did. The horses’ flanks

are rank with sweat and flies . . .

. . .

the sweet unsayable loss that’s gain

in drag. . .

. . .

I have a turnstile heart; it opens

madly and shuts just so.

In morning cold, the horses’

breath takes on the shape of terrible

blooms. The hoof-stamps sound less

urgently. I’m not talking about my heart.

This poem, and others, recall Dostoevsky’s obsession with rank suffering and his insistence that such suffering ends up purifying souls. While Stein explores this trope in poems like “Flower” and “Lemon and Cedar,” in others she reaches beyond it toward a melding of opposites. If “the sweet, unsayable loss” is “gain / in drag,” if experience is capable of being characterized as both “velvet and shit,” what are the implications for the human capacity to survive suffering?

Many of the poems, especially in the book’s first section, seem to speak from the poet’s personal experience, though Stein also portrays intimate relationships that read more like persona works than confessionals. In “Husband,” the speaker inhabits a Midwestern landscape, where she’s had a “tumble with the farmhand, rustler, / priest.” Addressing the husband, she outlines his inevitable demise:

. . .Solely

by my grace do you sit down to morning

rashers, jaundiced eyeballs

on your plate. Husband, they see as I do

the hour your use ends. I have meet help.

The fields near plough themselves, gloved hands

collect the dozens, the milk, I’ll soon have

all I need. A truce of soil and rain,

pest and feast. In such bounty

shall my finest secret

flush and swell. In such peace.

Peace, in this collection, often comes as a side effect of death. In the three-part poem, “Dead things,” the speaker arrives just in time to her mother’s deathbed. The mother’s eyes, “ice blue,” have closed:

I missed their final opening.

She died early the next morning.

I held my mother’s hand through this

though we hadn’t spoken in a year.

I’m next, she said. I will be, too.

Death’s awful continuity is mirrored not only in the poem’s narrative, but also in the exquisite balance of the last line, which contains two sentences of four syllables each. The repetition in this last line has a soothing quality in spite of the ghoulish experience.

Four of the poems in the collection, one in each section, bear the title “Quarry,” and Stein makes the most of the word’s multiple meanings: a place where rocks, sand, gravel, and minerals have been cracked apart from the Earth, the act of extracting, and an animal or human who is someone’s prey. The first “Quarry” depicts an excavated rock quarry and considers how “light hitting layers / that should be hidden” might be painful, and

and how when it rained

for a long time that absence filled

with suffering and we swam.

In the third “Quarry” the speaker is joined by a red-haired boy. The setting is an old excavation site already filled with water and waiting for swimmers. Developing the meaning of quarry-as-prey, the speaker looks back on her girlhood, wishing to substitute one act of violence for another:

. . . I still dream

that the red-haired boy held my head

under water

to spare me what the man did.

The final “Quarry” brings the reader into quarry-as-a-verb. It’s a nostalgic poem, celebrating the innocence of children—“the water covering that rich debris / was clear and pure and cold and so were we”—while expressing consciousness of the sinister matter just below the surface. Still, the poem encourages us to extract what benefits we can from memories like these: “Leaving we’d drag our feet. But we were lighter for the floating.”

Memory in these poems takes on opposing tasks: working the suffering of the past into a warning signal or talisman against potential suffering, while lightening old burdens with the “clear and pure” moments of the past. This is a Stoic vision that refuses to deny the existence of pain. As Stein writes in “Little fugue,”

cure has so many forms

the key is merely

to stay alive

In an interview with Deborah Kalb, Stein frames Terrible Blooms as an interrogatory vehicle of sorts:

The book asks, especially for women, how do we respond to violence? How do we protect ourselves and find our power and at the same time, live fully and freely and compassionately? How fiercely can we notice and experience and cling to and love what’s around us?

These are important questions for readers to ponder, especially in modern America’s fraught and dangerous political climate. Terrible Blooms offers no pablum as answer. It’s a book full of contradiction and complexity. Perhaps Stein’s purpose is to show what survival looks like through times of confusion, bringing language and meaning together for our flesh-and-blood bodies to speak, as in the collection’s final poem, “Mouth”:

my mouth was full

of mouths

there was

no end to it

Michele Sharpe, a poet and essayist, is also a high school dropout, hepatitis C survivor, adoptee, and former trial attorney. Her essays appear in venues including O, The Oprah Magazine, The Rumpus, Guernica, Catapult, and The Sycamore Review. Recent poems can be found in Poet Lore, North American Review, Stirring, and Baltimore Review. She’s currently at work on her second memoir.