by Alberto Ríos | Contributing Writer

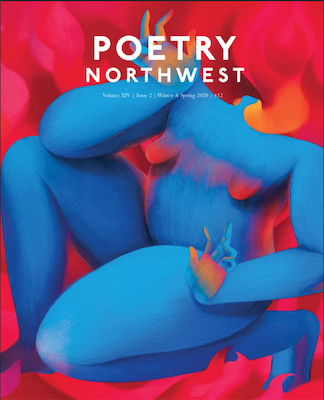

This essay first appeared in the Winter & Spring 2020 print edition of Poetry Northwest.

1.

First, Magical Realism.

What an intrinsically wonderful term, but it also brings so much baggage in tow.

Magical Realism, or Magic Realism, is not an intellectual movement, with a manifesto or a roadmap or a menu, and it is not summarized particularly well, therefore, in intellectual terms or dictionary definitions. All definitions limit, and Magical Realism is about possibilities, so that trying to define it is a way of wounding or diminishing it. Simply said, its definition is different every time. But the reason is simple: we are different, each of us from the other, and Magical Realism is, if anything, a literature of moments involving individual human beings, not generalities about them.

When I say Magical Realism, what do we think of? Enough with the ghosts.

Magical Realism is not so much about ghosts as possibility; not so much about the strange as a value judgment as the personal in actual experience; not so much about science as singular circumstance, what might be called personal science. It is a literature in continual exception to the rule, whatever the rule may be. In this country, we think of ourselves as founded upon precepts of individualism, while at the same time individualism—or difference, which is what that really means—is what scares us most.

A beginning explanation or exploration of Magical Realism is first an explanation of culture, with literature just one manifestation of that culture.

2.

But first, the term.

“Magical Realism” is a derivation of the Spanish phrase lo real maravilloso, and translates more literally as the marvelous real or marvelous reality. We hear in these re-phrasings a much stronger emphasis on the noun, reality, than on the adjective, magical. The Cuban writer Alejo Carpentier in his introduction to The Kingdom of This World coined the term for literature in 1949. Carpentier’s introduction is often considered something of a manifesto of Magical Realism and provided, at the time, a critical rationale for the vital second half of the 20th century Latin American Novel phase, a period starting in the late 1940s that is often referred to as “el boom.” Most readers and critics say it culminated with the publication of One Hundred Years of Solitude, which was published in English in 1970.

The four seminal essays on Magical Realism are:

- Franz Roh – a German art critic writing about art in his essay, “Magical Realism: Post-Expressionism” (1925)

- Alejo Carpentier – “On the Marvelous Real in America” (1949)

- Angel Flores – “Magical Realism in Spanish American Fiction” (1955)

- Luis Leal – “Magical Realism in Spanish American Literature” (1967)

Curiously, One Hundred Years of Solitude was written in 1967, so when Luis Leal wrote his essay, the novel did not yet exist. Clearly, the search was on for something that seemed inherently Latin American. The difficulty, however, was clearly laid out. He went on to say, “If you can explain it, then it’s not magical realism.”

In the rephrasing of Magical Realism as the marvelous real, we start to unravel something culturally important. “Magic” and “magical” are interesting words in this context. We as North Americans do not believe in magic. We are, however, entertained by it. Anything magical is operatively impossible by definition, and the impossible is many things—scary, in that it can seem powerful because we don’t know how something is done; child-like, in that it has the patently made-up elements of a fairy story or a fable or a nighttime story; uneducated, because whatever action is in question simply cannot be done (“everybody knows that”). Magic becomes jejune, quixotic, amusing, even as it is simultaneously memorable, and simply fun. But at the end of the day, in this context, it is dismissible. This is especially true as we stand it next to science, science as we know it.

Next, we have the word “realism.” Magical Realism. Dismissible realism. This is where the word “magical,” rather than being an assessment of the marvelous in this world, becomes dangerous. It is not much of a leap to see that culture can take the place of magic in this thinking. We can construct the phrase “Cultural Realism” to stand in for “Magical Realism.”

If an explanation of Magical Realism is first an explanation of culture, we can see that the stakes are high.

The stakes are high because, in a word, we do not believe other ways of living. Reality is our reality, whoever we are.

Magical Realism, rather than being multicultural, is something closer to otherculturalism, culture of the other, with culture taking the place of magic. Culture is different; magic is different. At a distance, they are marvelous. Up close, things get messy: what, exactly, are we eating tonight?

Yet, lyric leaps, metaphors, similes, new ways of seeing: these are all impossible possibilities. We are constantly drawn to—and repelled by—the not-possible, the magical, the entertainment. We are writers. This is our stuff.

Luis Leal, in his 1967 essay that I mentioned earlier, says this:

Magical Realism is, more than anything else, an attitude toward reality…. In Magical Realism the writer confronts reality and tries to untangle it, to discover what is mysterious in things, in life, in human acts. The principle thing is not the creation of imaginary beings or worlds but the discovery of the mysterious relationship between man and his circumstances. In Magical Realism key events have no logical or psychological explanation. The magical realist does not try to copy the surrounding reality or to wound it but to seize the mystery that breathes behind things.

3.

Well, what are these things and where do we find them?

I would like to start a discussion of culture and Magical Realism by talking about language.

Language is a blueprint for culture. We put ourselves into our words, from grocery lists to theorems. Needs are certainly encoded into language, but beyond those needs we see that imagination itself is just as much encoded into language, and different cultures have different languages. How is this possible? It suggests that imagination is dynamic, and even that facts themselves are dynamic.

And we think we understand this dynamism, precisely in that we understand each other’s languages. Some people learn different languages, however, in order to speak English better, or farther, or more dominantly—English or whatever their dominant language might be, whatever their language of thought. This speaker does not believe in what another culture is saying or offering; what is learned instead is simply how to say what they themselves already believe, just in another language. It’s theater. The learner learns the words, but not the culture.

The stronger reason to learn different languages, however, is to learn to walk in different geographies, of both place and imagination, the sometimes very different places we inhabit even if we live right next to each other.

Let me demonstrate something remarkable about language. We think we know or can understand other cultures because we can translate how languages work. But demonstrating what is, really, a foundational difference in how other languages literally conceptualize the world in different ways is simple. In English, if I drop a bottle, I would say [I], capitalized-I, me, I, [dropped] then move to whatever’s at the end-of-the-sentence [the bottle]. This is rugged individualism in its smallest incarnation: “I dropped the bottle.” However, if I were to verbalize the same moment, render it and speak it in, for example, Spanish, as one of the romance languages—and other languages around the world do this as well—that same moment is foundationally different, profoundly different. If I drop the bottle, I would say, “se me cayó la botella,” or (wait, don’t look at me!) “the bottle, it fell from me!” We were both there! I might have done it but the bottle might have done it, too! I didn’t do it—at least, not by myself! I am not the boss of you. We did it together. We were partners to the moment. This suggests the possibility of an inherent life in things. It suggests that We are not in control of the universe. This is not rugged individualism. It’s what I would call rugged pluralism: we’re in it together. We do not know everything, and we are not in control of things in the ways that we might think. The bottle and I—maybe together we’ll be able to figure out what happened, but not me alone. That’s just my side of the story. A verb moment is an act of community, a partnership with the world, with the universe.

4.

Following from this idea of an inherent life in things, so many languages, certainly the Romance languages, are gendered, which can seem strange to, for example, and specifically, English speakers, which maintain insistent neutrality in this regard. In Spanish, for example, we have el and la, el ojo, la pierna. Gendering language suggests the sexual, with the possibility of engagement, of he or she or it encountering, or he and he or she and she or any other permutation, perhaps whole orgies of encounter—a singer warming up with lalalala, elelelel. All of those shes, all those hes. The world is suddenly fertile in this imagination, and everything is going on all the time, with or without us. It’s not just us: it’s everything.

English, on the other hand, neuters language, and the engagement is the-the, not el and la. I don’t know. But when my el ojo sees her la pierna they go off together in spite of the two of us who remain sitting here. In neutered form, the world behaves itself, so to speak. In its gendered form, songs get written about what happens then.

5.

Next, regarding language, one word does not capture the thing. The Surrealists worked with that, different people worked with that, but I am not sure we have learned the lesson. One word does not capture the thing. One language does not hold all things. More words and different words mean more and different perspectives, which is an immediate widening of our world. Poetry helps us with this, always in search of more words to describe the same thing, this hunger for what languages together do, what minds collectively seek and assert. But if I hold my pen and can only call it “pen,” I in some sense have thought myself to have captured it. It is a pen. But a pen simply and only. But when it suddenly also becomes a “pluma,” then it leaps into dimensionality, from one-dimensional—just a pen—to all of the ways it can be said—multidimensional, and I have not captured it at all is what I find out, especially as I come to see that it has several thousand other ways as well to be said and conceived of. The pen, suddenly, becomes a wild horse in my hand, vibrant, and in holding it and calling it a “pen” in this moment, I am just plain lucky to be able to do that. I call it a pen and for this one moment I connect to it but I have not captured it, not when you know it has other names and can be turned around and made three-dimensional in your hand through language.

This reminds me of something Pablo Picasso said in 1950:

Reality is more than the thing itself. I look always for the super-reality. Reality lies in how you see things. A green parrot is also a green salad and a green parrot. He who makes it only a parrot diminishes reality. A painter who copies a tree blinds himself to the real tree. I see things otherwise. A palm tree can become a horse.

He is saying that when we see a green parrot we are, in that moment, also remembering having seen a green salad, and—in that instant—we connect the two, regardless of the time and distance between those two places. We bridge them in that moment. We are an impossible Colossus standing in one time and another, one place and another. It is not a case of either or, but also and. You get to have the green parrot and the salad in that moment, if you see it.

Because of that, we are more connected to the world, more in it, not alienated or removed or disjointed from it. That the parrot is also a salad is normal enough. It is Us in the act of thinking, of living. We are the act magnificent. Not to make that connection is an impoverished view. When I hold a pen and know it is also a pluma and its ten thousand other incarnations, I am in the presence of a magical reality, mundane as it at first might have seemed.

6.

I grew up on the border, my father from Mexico and my mother from England. I grew up, really, around my father’s family, and for all practical purposes my first language was more or less Spanish, though on the border language is so often beyond label. But, in speaking Spanish, I grew up repeating a mantra of words that at the time and as a child seemed perfectly reasonable. In retrospect, I understand now what the phrase both meant and gave to me as a sensibility. The phrase was, “¿Que quiere decir . . . ,” a question that was always paired with a word, such as, “¿que quiere decir plátano?” In a dynamic translation, the question is simply a child asking what the word “banana” means—”what does banana mean?” But in a more literal translation, the question is actually worded: “what does the word ‘banana’ want to say?” It is as if, once spoken, the word becomes an oral artifact, an entity existent on its own, desirous of attention, consequential, perhaps capable of action, all in spite of the speaker. It is as if the word “banana” has a life and a will of its own.

Knowing that “plátano” means “banana” is nice, but it is just the beginning of things, not the end. As English speakers, we think of the dictionary as the final “word” on words; as a speaker of other languages, I would posit that the dictionary is just the beginning of the story, not the end. Aside from its definition, who knows what “plátano” wants to say. In this moment, the word has power beyond us.

This view forges a belief in the possible by not eliminating it, not by science, not by experience, and not by lack of imagination. Anything is possible, anytime. And once imagined, the pathway is set.

7.

After single words, whole artful moments themselves are also constructed in a different paradigm. The movement of life can be conceptually distinguished. In Latin American representations, the basic structure of a simile, for example, is often reversed. Instead of “this is like that,” it is “that is like this.” We instruct the world vs. the world instructs us. It’s that rugged individualism versus rugged pluralism again. In Juan Rulfo’s novel, one of the definitive magical realist texts, Mexico’s most famous novel, Pedro Páramo, for example, a character notes and laments that someone has died, and follows this by saying that his shoulder hurts. This is the reverse of my shoulder is killing me. Instead of the character whining into the world, the keening of a death comes to put itself in his shoulder. It might seem like a non-sequitur if we are not used to reading a simile in that order.

This moment reminds me of something of my own, from the poem “Some Extensions on the Sovereignty of Science”:

The reason you can’t lose weight later on in life is simple enough. It’s because of how so many people you know have died, and that you carry a little of each of them with you.

I liken the movement in this process as a distinction between an airplane taking off—how it works in English—and an airplane landing—how it works in Spanish. To a reader of English, this directionality may well seem like a non-sequitur, with the hurting shoulder not seeming to follow the announcement of a death. If someone died, let’s talk about it, we think, not about your shoulder. It does not seem to follow.

But in fact, the comparative elements are exactly the same, simply presented in “reverse” order. An airplane landing, rather than taking off. It is akin to the unfamiliarity of hearing Friday Thursday Wednesday Tuesday Monday, which in that iteration do not sound the habit of their “normal” order, or hearing YXWVU in a row—again, simply articulated “backward.” The juxtapositions are still there, exact, and yet the impact is new or odd, even magical.

8.

Let me move to some sociological realism, something still tethered to language but now moving us into a consideration of what language talks about. Its content. Its life.

Even here, the airplane landing or taking off is at work, the rugged individualisms and pluralisms, all working in “other” ways.

Let us start with an example: birthdays in Latin America. Traditionally, birthdays are not celebrated in the same way as here, and indeed birthdays are not celebrated at all, not in a way we would recognize. Instead, one celebrates one’s saint’s day. Things are changing, of course, but this has been a traditional approach to celebration. In this country, a birthday separates us, distinguishes us from everyone else, singles us out of the community—more candles for me, I’m so glad you’re all here to sing, thank you. A saint’s day does almost the opposite: it connects us to everyone else, and something else, and in fact takes the emphasis off us and places us into a greater community.

9.

Similarly, there is a wonderful term in Spanish, the word tocayo. In Latin America, and in Spanish specifically, tocayo presents us with a connection found. A tocayo is a person who has the same first name as yours. And in Spanish, there are often some kick-ass, old-world, ten-syllable first names. The word tocayo presumes a relationship of shared experience between two people who do not have the same family name but who do share the same first name—a namesake but something more as well. Two people both named Perfecto or Espericueta are simply thought to have something clear and palpable in common, to have shared many experiences because of that name, and so they are in this way related. It is a people’s approach to relationship, rather than simply an inherited one.

The word says: Experience connects us.

People who have gone through war together, or shared adventures, or who in some way have gone through something meaningful together often refer to this kind of relationship, even though in English there is no particular word to catch its substance. Indeed, we often resort to words from other language to fill the gap: Compadre, we say, for example.

10.

Furthering the artful moment, let me speak now about tone. I think this is key to the understanding of magical realism, and its enjoyment as well. This may be the most important thing to understand.

Tone is everything. It comes from belief. I believe the text, says the writer; I’m not inventing it. I believe the text. It works on a simple premise: nothing so important and nothing at all unimportant. G.K. Chesterton once observed that “the telescope diminishes the universe while the microscope enlarges it.” Nothing so important and nothing at all unimportant. It is at once Marxist and Buddhist and other frames of historic and world thought. The thing is, the work of making that manifest on the page is in evidence here, the hard work of it, on these pages. For example, in Garcia Marquez’s short story, “The Very Old Man with Enormous Wings,” we are watching a man who has landed in a back yard. By the way, anyone strange in Latin American fiction who is from far away and looks odd is always called Norwegian. It’s like the Latin Americans, a long time ago, figured there’s nobody stranger, farther, more different than the Norwegians. It will be no surprise, then, when in this story, here is a man who has featherless wings, he is sick, flea-bitten, he has landed in this courtyard, brought in from the storm, and somebody says: “I wonder if he’s Norwegian?”

As a further note, we might take notice how, in that story, Garcia Marquez assiduously avoids the word “angel.” He lets the priest bring it up in one little small moment, but neither he as a narrator brings up that word, nor particularly do the people in the story. It is simply one possibility among many. Over time, the man gets healthier. They take him out some food, sort of like feeding the cat. He gets better, the feathers start to come, it starts to be spring, and he starts to feel good. He is doing little test flights. At the end, he is doing a test flight and achieving some height with his wings, and he starts to fly away. It’s a miracle. This is all being told to us by the woman of the house, who is looking through the kitchen window at the courtyard as all of this happening, and—more importantly—as she is washing the family dishes. That is the critical observation and a perfect example of first things first: oh yeah, it’s a miracle out there, but I really have to get these dishes done. Get over yourself, she seems to be suggesting. Nothing so important, and nothing at all unimportant.

There is a similar, wonderful moment in One Hundred Years of Solitude, where the character, Remedios the Beauty, who if you will remember was so pure and so distinct in the world that “clothes would not stay on her”—that is my favorite line. When she reached adolescence, things changed, and the people in the town felt that she would distract the young boys. So they contrived, finally created a shift, a very plain thing that they could put on her and it could stay, but of course it drove the young boys wilder because they knew she was naked underneath. Go figure—it’s human nature.

At one point, Remedios is with the women of the village of Macondo, and they are all doing this very important thing: washing sheets at the river. Sheets were an important commodity. They did not treat it lightly. They needed to be washed, the laundry. While they were doing this, Remedios also was washing a sheet and suddenly she begins to be assumed bodily into heaven. As she washes the sheet, she starts to rise with it. Everybody—this is a wonderful moment—they are all watching her and all washing sheets. I think somebody even says, “I think it’s a miracle!” Most important, however, as she is rising into the clouds, somebody has the presence of mind to stop and shout up at her, “Drop the sheet!”

First things first. Nothing so important and nothing at all unimportant.

First things first suggests a hallmark of Magical Realism that hides in those examples: necessity. It is first things first because that is how we are living, and it is how we get through the day. What needs to be done needs to be done.

It is simple, and profound, necessity. But so often the act of necessity comes off as humor, in the inherited great tradition of Spanish literature. To use classical terminology, tone so often derives from the delivery of the narrative as litotes—understatement—in the middle of hyperbole—overstatement. If it is not humor, then it comes off as flatness of treatment, non-reactivity, deadpan almost, which is the great comedian’s trick, or else we see the text already moving on even though something “big” has just happened, giving the “big” no more time or notice than whatever is next and whatever came before. In other words, the text does not privilege the “big,” and raises up to respectability the smallest moment. Witness the character Melquíades flying around on a flying carpet in One Hundred Years of Solitude, with nobody thinking much of it, since they had heard about these things already in stories. They had heard about flying carpets. Flying carpets were old news, if you believe the text—and if you yourself were entertained by stories of Aladdin when you were young.

By gentle contrast, Emily Dickenson, for example, in one of her poems, asserts, “I dwell in possibility.” In Evita, the actors sing about the “art of the possible.” But each of these in its own way makes possibility special—the reserved subject of a poem, an ominous bargaining approach.

Narrative telling in this literature is never a series of exclamation points or OMGs, while the smallest details are rendered with diligent attentions. Contemplation in place of breathlessness—or at least its equal. Again, nothing is so important, while nothing at all is unimportant.

And in this practice, priority is given to that ethos of first things first. This is the necessity that we see everywhere. Necessity and the ability to laugh at these human difficulties. It’s okay: but we can make the distinction between laughing with and laughing at. They are different. To laugh at ourselves as human beings, and in that way, laughing with, turning laughter into something powerful, rather than simply the low result of entertainment solely.

11.

All right. How does this all play out in real life? We have had some literature, some artful acts of the imagination, but literature does not spring out of the blue. Where do we find this magical realism in real life in order to start looking for how this literature comes to be?

In 1987, a family was about to be evicted from their house in a barrio of Mexico City. All of a sudden, a pick-up pulls up in a cloud of dust, fish tails, and in the bed of the truck stands a man in a superhero costume who announces to the world in that moment and to the group that had gathered—there were neighbors, there were the police, there was the poor family crying—he shows up in this pick-up truck, stands, and declares, hands on hips: I am here! SuperBarrio!

This was in the great tradition of Mexican wrestlers, which is hard for us to conceive of here except for now, the World Wrestling Federation, it has gone crazy. This has been going on in Mexico for years, this idea that it could happen: that SuperBarrio, whoever he is, could come to the rescue. In fact, the shock of it all just completely discombobulated the police: they left, everybody was cheering, the family got to live there longer, and the day was saved. The day was saved by that simple, human action—well, that and a costume.

Suddenly, SuperBarrio started showing up everywhere. Sometimes he was short and pudgy, sometimes tall and lithe. However, he liked to give interviews, whoever he was. This was my favorite thing, when he started showing up in public. His most memorable line in interviews was magnificent on so many levels: “SuperBarrio, we like what you’re doing,” he would be asked, “but who are you? And every time we see you, you look different!”

He answered, “that is because SuperBarrio is everybody!” It’s a great line. It reminded me that, around the same time, the Zapatistas were fighting in Southern Mexico. If you remember, their leader was a man called Subcomandante Marcos. He also had a mask. He was a man of mystery. Everybody imagined him to be handsome, dashing, that sort of thing. Very romantic. What was intriguing was his name, his title: Sub-Comandante.

Who was the comandante? The people, of course. In a genuine social action, one could never achieve, nor want, a better rank than “Subcomandante.”

Later, in 1988, Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas, the son of former president and legendary Mexican figure Lázaro Cárdenas, was running for president of Mexico. In a photograph, Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas is shown leading a huge rally at the Zócalo in Mexico City. He is at the front of the masses, locked arm in arm with two others: on his left, a priest; on his right, SuperBarrio. This is magical realism at its best, sprung directly from life and offering itself in plain view to the world.

SuperBarrio Gomez, as he later started to be known, evolved something he and others called the politics of the possible. It was not a new idea, perhaps, but it was being newly lived. The politics of the possible. When I heard it, it was a pure act of pataphysics, defined by French playwright Alfred Jarry as the science of imaginary solutions. One of SuperBarrio’s platforms to this day is free citizenship. Everybody should be able to live wherever they need/want/can live. That is at odds with a lot of what is going on in the world right now, certainly in Arizona. To make his point, SuperBarrio ran for president of the United States in 1996. He lost. But if SuperBarrio seems funny to us, we can find another side.

This sensibility is immortalized on occasion in this country as well, though we are not likely to laugh. In his book Why We Can’t Wait, first published in 1964, the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., wrote:

More than twenty-five years ago, one of the southern states adopted a new method of capital punishment. Poison gas supplanted the gallows. In its earliest stages, a microphone was placed inside the sealed death chamber so that scientific observers might hear the words of the dying prisoner to judge how the human reacted in this novel situation.

The first victim was a young Negro. As the pellet dropped into the container, and the gas curled upward, through the microphone came these words: “Save me, Joe Louis. Save me, Joe Louis. Save me, Joe Louis . . .”

We see SuperBarrio, with his costume, in the Mexican tradition, and we are laughing. But the impulse is something much more: who will save us, who will help, when there is nobody else left? Religion, of course, has often answered that call. We are complex as human beings, however, and no one answer has yet served us all.

Many people have told this story of the execution. It may be urban legend, finally. But if as people we made it up and passed it on, accurate or not, it expresses a collectively inherent truth in the form of a hope or a prayer. Otherwise, we would not pass it on. It would have no reason to be passed on. We want to believe that we will be helped when we need it.

This is the willing suspension of disbelief that we ask for in writing—superheroes! SuperBarrio! Joe Louis! The willing suspension of disbelief so we can get to the belief that structures a story. In these examples, however, it is not just literature we are talking about, but life itself. The culture give rise to these possibilities, all cultures do, and literature fleshes them out. Literature and art and song and all the rest. Sometimes we laugh at our human condition in the process, and perhaps save ourselves.

12.

So, this is some of what Magical Realism has been: what it has offered and what it offers us still. But what is Magical Realism in the 21st century? What is it going to be?

The first thing, I think, is that we will come to Magical Realism’s 20th century gifts late. We will find Magical Realism in the 21st century—we will have read it in the previous century, but we will find it in this one. We will get it. We will understand it. We will stop laughing at it, dismissing it, and learn to understand that there is a greater belief beyond the disbelief, and that it takes some work to get there. It may sound like other words and funny stories, but we will find it everywhere. It is not strange. And, rather than fearing or dismissing, what we will be doing is finding cultures and languages and, more than that, perspectives that add to our own and help us in that moment to see ourselves better.

This is a funny thing to hear myself say, coming from Arizona and all that is going on right now. The anti-immigrant—which is such a disingenuous word—the anti-Mexican fervor right now is loud, vitriolic, mean-spirited, and un-American.

I think the better of us all, and the better of my state. We’re just having a bad decade.

Albert Einstein said a wonderful thing, which has curious bearing on all this. He said that you cannot solve a problem at the level at which it was created. This is why, as a writer, you can edit someone else’s work so easily but cannot begin to figure out how to fix your own. This is a metaphor for us, right now. We see ourselves, and we can’t seem to get better. Perhaps perspective—many perspectives—is exactly what we need, not what we should fear.

13.

Poetry offers us common ground. The great secret to Magical Realism, and the reason poetry is not often called “magical realist,” is that the prose of Magical Realism is, I would say, poetry. It arguably follows the open rules of poetry, but with a lot more words. It is patient with those words, however, and often tender enough to take time with the single, quiet voice saying, this happened to me, or I think I saw this outside the window. It does this, takes this time, in the middle of a world that always wants something else.

Poems, with their sense of moment rather than plot, may be a good starting point for gathering us in an understanding of this literature. That may be the bridge—it may not be fiction to fiction. It may be fiction to poetry to fiction.

You’ve got to not take me too seriously, by the way. Magical Realism is often funny and fun. I don’t want to kill that. The key point in all of this is that ultimately these moments of social understanding are intrinsic in the works of literature, not extrinsic to them. They are organic, at least as much as contrived. There are still writers at work lying through their teeth, making stuff up. But there’s a lot more real than we might at first expect. The moments we think of as magical realist are so often not decorative at all, but organic. It may seem odd to think that magic carpets are not difficult to understand until you grasp that you understood them perfectly well in childhood. What happened?

Magical Realism shows us our shared world in a way different from what we’re used to. We may dismiss so much of it, but at our peril. Ghosts—that is always the association to Magical Realism—ghosts, but ghosts were not invented by Magical Realists. At the same time, neither have they been ignored. Possibilities of all sorts have been welcomed into this literature with open arms, for good and for bad, but with open arms—welcomed into this literature, through its multiple languages, and through its multiple cultures, all of which stem, in one form or another, from the mestizo—the great human mixing.

And I think the open arms are, finally, our arms. Our 21st century arms. Maybe not yet. Certainly not before the next election. But I think we are all listening for the song beneath the white noise of our everyday reality. We know it’s there. We have used the words dream, waking dream, daydream, and a host of other similar words to define and sidestep the place in which we hear the special song, but it may turn out to be everywhere. That’s my hope.

—

Alberto Ríos, Arizona’s inaugural poet laureate and a Chancellor of the Academy of American Poets, is the author of eleven collections of poetry, including The Smallest Muscle in the Human Body, a finalist for the National Book Award. His most recent book is A Small Story About the Sky, preceded by The Dangerous Shirt and The Theater of Night, which received the PEN/Beyond Margins Award. Published in the The New Yorker, The Paris Review, Ploughshares, and other journals, he has also written three short story collections and a memoir, Capirotada, about growing up on the Mexican border. Ríos is also the host of the PBS program Books & Co. University Professor of Letters, Regent’s Professor, and the Katharine C. Turner Chair in English, Ríos has taught at Arizona State University for over 35 years. In 2017, he was named director of the Virginia G. Piper Center for Creative Writing.