by Helene Achanzar | Associate Editor

One More Thing is a series featuring Poetry Northwest contributors and other writers in conversation. This installment features Associate Editor Helene Achanzar in conversation with poet Tiana Nobile. Tiana’s poem “Harlow’s Monkey” can be found in the Winter & Spring 2021 issue of Poetry Northwest.

Editor’s note: This conversation began in March 2021, days after six Asian women were murdered during a series of mass shootings at spas in the Atlanta area. The rise in reported anti-Asian violence during the Covid-19 pandemic in America does not signal new phenomenon. Rather, it’s a continuation of the United States’ colonial, imperial, and otherwise systemic harm of Asian people both in and outside this country.

Helene Achanzar: It would be disingenuous for me to begin this conversation without acknowledgement of the deep grief our communities have been feeling. As we watch the rise in anti-Asian violence across the country, I return to a question that plagues me in times like these: What are the limitations of poetry? I wonder what material power it has in the face of hate.

Tiana Nobile: I’ve also asked myself this question, especially in times of despair. What’s the point, and who cares about my poem? This time, though, felt different for me. I spent most of last week utterly in mourning, and as the immediate grief began to subside, it was replaced by profound rage. I began to feel an urgency, not only in the theoretical power of poetry but in our collective power as poets.

I just read Christopher Merrill’s article “In Burma, ‘they have come for the poets.’” Since the coup in February, at least nine poets have been detained by the military. What makes poetry so dangerous? I’m thinking of poets who have suffered throughout history for writing truth to power, like Lorca and Mandelstam. Especially in times like these, it’s important we remember the political power of poetry. Writing poems is an act of resistance against erasure. It proves we exist. When white supremacy is trying to render us invisible, writing poetry is a radical act. This isn’t, and shouldn’t be, the only way we’re resisting, but I do think it’s a really important piece of the puzzle towards liberation and justice.

Helene: It’s hard to resist the idea of poetry as frivolous, but what you say is plainly true: part of poetry’s power is in its resistance to invisibility. Thank you for reminding me of that.

Reading your poem “Harlow’s Monkey,” I’ve been thinking about how you explore liberation through and beyond the non-human. When you write about the “fresh liquor / of unchained thought burning the roof of our mouths,” there’s even a sense of wilderness in your language, of an unrestrained, intangible effect on the bodily. What was your journey toward Harry Harlow’s work on the psychology of monkey’s experiencing maternal separation and social isolation? How did you find yourself in it?

Tiana: I was introduced to Harlow and his work by fellow Korean adoptee, JaeRan Kim’s blog, “Harlow’s Monkey: An Unapologetic Look at Transracial and Transnational Adoption.” I was really intrigued by this idea of adoptee as monkey, and it opened the floodgates for my research into attachment theory and its impact on childhood development. While I was leaning into that, I was simultaneously doing a deep dive into my own adoption file. It was fascinating to notice how the cold and rigid language of psychological studies so closely resembled the language of adoption. Initially, I thought about the monkey as a helpless and vulnerable recipient of Harlow’s various surrogate mothers, most famously made of cloth and wire. From there, I began to imagine more versions made of alternative materials, such as rock and wood and paper. Through the course of the book, the monkey gains more autonomy, culminating in the liberatory moment of “Harlow’s Monkey.”

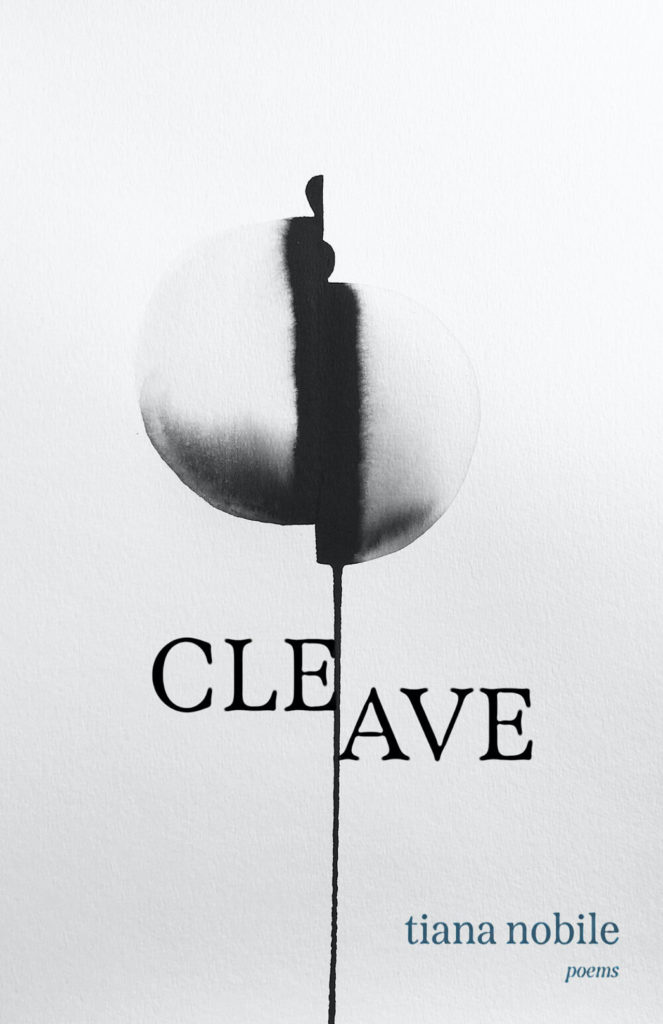

Helene: I read a similar arc toward liberation in Cleave, your debut collection, where knowledge and possibility are increasingly within reach as the collection progresses. Can you say a bit more about the role of revelation in your book? I’m thinking particularly about “Child’s Pre-Flight Report” and “To Whom It May Concern:” – two poems that take the form of adoption documents, and whose forms are inherently revelatory.

Tiana: My father is a lawyer and keeps meticulous records. Growing up, I always knew there was a folder with the label “Tiana – adoption” in the filing cabinet in his office. As a kid, every so often, I would go in and thumb through the thick stack of papers. At the time, I didn’t understand most of it, but it was the closest I could get to an origin story. Re-engaging with this file as an adult was enlightening; I learned so much by both what was there and what was missing. For example, at one point, I discovered that I don’t have a birth certificate. Some of the documents were standardized forms while others were paragraphs specifically about my infant self. Using them in my poems was a way for me to fully immerse myself in the language of such stiff and detached records. Through erasure and collage, I could complicate the narrative and call attention to loss.

Helene: In this collection, reclamation of the self seems to happen as much through the information that’s present as what is absent. In “Moon Yeong Shin,” Cleave’s opening poem, you begin, “Written on the white slip at the bottom / of a polaroid, cut off by the frame: / a name.” What did it mean to have a name, then unearth a name? Similarly (or perhaps oppositely), in your OED poems, what was the process of rediscovering words that already had a meaning in your life—mother, migrant, moon, monkey?

Tiana: I’ve often felt haunted by Moon Yeong Shin. I always knew I had this name but I didn’t know who gave it to me or what it meant, and it was a constant reminder that I was someone else before I was me. Or that I could’ve been someone else. Growing up in my white family, full assimilation was the modus operandi, and I rejected this name and everything it stood for. I realize now that I was caught in this binary of Tiana Nobile as the good daughter and Moon Yeong Shin as the bad mistake. As my understanding of adoption deepened, I started to form a different relationship with my Korean name. Over time, I was able to open myself up to it, not just as a relic of a past life but as an active part of who I am today. Like you mention, I explored similar ideas in my dictionary poems. Entering a word (or a name) to find what’s hidden beneath the surface can really burst a poem right open.

Helene: Besides all the work that goes into releasing a first book—congrats!—how else have you been spending your time?

Tiana: Since the pandemic forced us to stay home, my partner and I have entirely revamped our house. We re-painted every room, replaced the kitchen cabinets with open shelves, bought a new yellow couch. In the latest update, Ross painted this amazing, geometric, multicolored mural in the living room. It’s also spring again, which means I’m spending lots of time in my garden. We planted tomato, cucumber, basil, and green bean seeds a few weeks ago, and they’ve just started to sprout.

Helene: I’ve noticed people turn to houseplants and gardens during the pandemic. Something about having things to tend to, care for, love. Something, too, about growth when other parts of our lives feel stagnant. How long have you been growing food? Why did you start?

Tiana: I’ve been casually gardening for years with varying success. In the past, every time I planted tomato seeds, the plant itself would get huge but never produce any fruit. It wasn’t until lockdown that I committed to it in earnest. I finally had the time to tend to the garden daily, and it paid off; last spring I harvested my first tomatoes! There’s something therapeutic about growing and making your own food. I’ve been making pasta from scratch for a long time and hopped on the sourdough train during the pandemic, too. Working through dough—and dirt—definitely helps me find grounding and quiet all the background noise.

Helene: Working with food to create a dish seems commonplace, but working through materials to create food is like magic, like alchemy. Has gardening and making things from scratch changed your relationship with food?

Tiana: It’s so special to be able to sit down for a meal and say, “I grew this from seed.” I don’t have children, but I have a cat (as you know!), and I feel like tending to the garden is like caring for a pet. It requires care and attention but you also have to trust it and let it do its own thing. I learn a lot when it doesn’t work, too. Like when the tomatoes didn’t grow or my sourdough doesn’t rise—it forces me to slow down, step back, and think about what I can do better next time.

Helene: As someone who lives with cats for the first time, I’ve recently learned this lesson on letting a thing be. I didn’t grow up with pets, and I could have never imagined I’d find my relationships with my cats to be so nourishing. Tell me, what does it mean to you to be nourished?

Tiana: Ooh what a good question. When I think of feeling nourished I think of joy. These days, joy means sleeping in on Saturday morning. It’s reading on the couch with the windows open, my cat curled up on my side. It’s drinking wine with friends on the bayou as the sun goes down.

—

Tiana Nobile is the author of Cleave (Hub City Press, 2021). She is a Korean American adoptee, Kundiman fellow, and recipient of a Rona Jaffe Foundation Writer’s Award. A finalist of the National Poetry Series and Kundiman Poetry Prize, her writing has appeared in Poetry Northwest, The New Republic, Guernica, and the Texas Review, among others. She lives in New Orleans, Louisiana. For more, visit www.tiananobile.com.