by Risa Denenberg | Contributing Writer

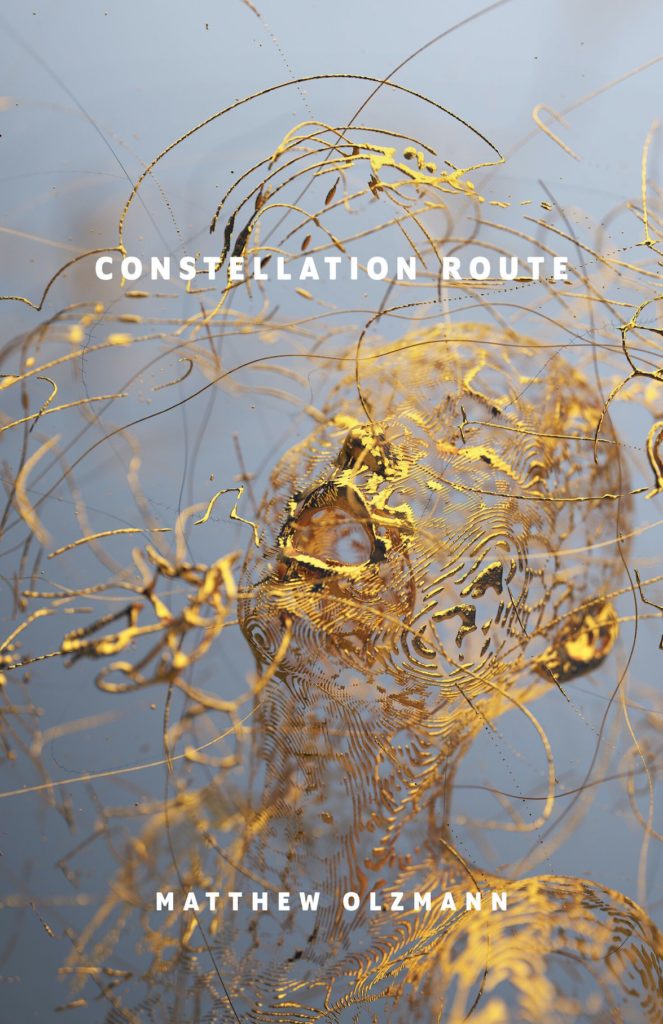

Constellation Route

Matthew Olzmann

Alice James Books, 2022

Constellation Route, the title of Matthew Olzmann’s new collection, is an apt one for a book of poems that create patterns out of bits; for instance, the three stars that make Orion’s belt, or Hansel’s trail of breadcrumbs. It is Olzmann’s talent—possibly his obsession—at finding meaning in the patterns of disparate elements of the universe that makes this a book I couldn’t put down.

Olzmann reifies definitions, and then bends them, similar to the way a constellation, viewed from earth, appears to form a coherent figure in the sky. In these poems, Olzmann follows narrative along known routes to unfamiliar destinations, often with side trips and digressions. The book’s title reveals both a pattern (a constellation)—if you can find one—and a set of directions (a route)—if you can follow it.

Many of the poems are humorous, some are outright funny—such as the one with a man walking into a room and saying, “Let there be light”—then flicking on a switch. I think what Olzmann is going for is the confluence of the sublime and the ridiculous—a sense-making discovery of how objects work or fail to function, how communications reach their intended post or get lost in the mail, how projects are created and destroyed and re-created.

In an interview with Olzmann at The Rumpus, writer Julie Marie Wade asks him to tell his origin story as a poet. He replies that when he started reading poetry in high school, he began to see poems as:

… a way to explain complicated things that were happening in the world around me. … I started feeling that a poem might give me a new way to experience, consider, or understand some shifting emotional aspect of the world or my daily life. Poems helped me make sense of what didn’t make sense.

The title poem starts with the lines, “I spent at least five minutes looking for my glasses / when they were on my head,” then, later in the poem, this: “A star route is an obsolete postal term / for a route given to an outside contractor instead / of a regular mail carrier.” “What?” you say. Keep reading. The foremost confluence in Constellation Route are letters, and how they are mediated and delivered. Throughout the book, the word route is used as an ongoing riff on the “Glossary of Postal Terms” published by the US Postal Service. There you can find terms such as “cluster box unit,” “unscheduled arrival,” or “M-bag.” Some are ridiculously self-explanatory, while others are ridiculously bureaucratic. In Olzmann’s hands, they are priceless fodder.

Olzmann’s poems mix despair with cat-like curiosity, pair grand jetés with detour signs, and contain all of it within a search for meaning—or, if meaning is unreachable, at least thoughtful consideration. Most of the poems’ titles begin with “Letter to” followed by letters to: famous people (“Letter to Bruce Wayne); the poet himself, from objects and eras (“Letter to Matthew Olzmann from the Roman Empire); and assorted specters (“Letter to William Shatner,” “Letter to My Car’s Radiator,” “Letter to a Bridge Made of Rope”). An impressive bit of trickery here is that many of the letters-turned-poems were actually written to Olzmann by other contemporary poets. That Olzmann’s engagement with other poets shows up in his poems is quite a gift to any reader who also happens to be a poet engaged with other poets. I don’t mean to suggest that non-poet readers would be baffled by that aspect of these poems, but, for me, it added another layer to my experience of the book.

Olzmann writes with a penchant for allegory and ethical dilemmas, but these poems avoid parable or pat answers. He can’t tell us what he doesn’t know to be true, and yet there is inestimable truth in his questioning—and an abundance of compassion. In “Letter to the Horse You Rode in On,” he grants a horse “certain provisions,”

under the law. Granted the law is one

I just make up, but those who acknowledge

its validity will adhere to the following rule:

One does not, under any circumstance say “fuck you”

to a horse.

The poem’s allegory is summed up in these lines:,

No, dear horse, you are proof that one does not

have the luxury of choosing the burden

one carries. Fate makes an animal of us all, and rides us

through the village at sunrise where we are judged.

But we designed those villages.

There are also poems of witness in Constellation Route. Witnessing harm harms the witnesses, along with harm’s targets, and, Olzmann is quick to point out, its perpetrators. In “Letter Written While Waiting in Line at Comic Con,” there is no comic book hero; instead, there is this uncomfortable reflection:

Last week, in an alley, I saw a man punch another man

until neither looked like a person.

There are hundreds of reasons like this

to long to be from some other galaxy

century, or dimension.

In “Fourteen Letters to a 52-Hertz Whale,” there is a yearning to assuage the great whale’s loneliness:

I’m sure it’s unbearable out there, swimming through eternity, calling out and calling out and calling out and calling out and never getting a reply, never a kind word in response.

Wherever you are, I hope you’re being careful.

I read this as a poem about a whale that sings at a frequency no other whales can hear, but also as a commentary on our great loneliness through the years of the pandemic. I have my own impulse to sign off emails with, “Be careful out there.”

Imaginative leaps abound in these poems, at times as a shield against witnessing horror. Such leaps often open doors, glance through windows, cross bridges, or suggest alternative scenarios. In “Psychopomp,” Olzmann imagines what may happen after hours,

. . .when the Post Office,

closes for the night. It’s conceivable they

pat each other on the back, punch out, go home.Or maybe they host rituals of ambergris and ashes, dancing

nymphs, a sacrificial lamb. Could happen. Not likely, but how

do we know?

The book steadily gives us poems that search deeply for a meaning that can only be constructed from the single point in the universe that the poet stands upon. In “Letter to Someone Living Fifty Years from Now,” present day anxieties emerge in the form of an apology—a confession of longing and loss:

Most likely, you think we hated the elephant,

the golden toad, the thylacine and all variations

of whale harpooned or hacked into extinction.It must seem like we sought to leave you nothing

but benzene, mercury, the stomachs

of sea gulls rippled with jet fuel and plastic.

Is this ecopoetry—poems which detangle the interrelationships between humans and planet Earth? Within that frame is the work of gifted poets such Forrest Gander and Camille Dungy. Olzmann clearly shares similar concerns, and he follows them along an imaginative route with a winsome combination of warmth, compassion, and confusion. The poem continues, seesawing along a tenuous course:

You probably doubt that we were capable of joy

but I assure you we were. We still had the night sky back then,

and like our ancestors, we admired

its illuminated doodles

of scorpion outlines and upside-down ladles.

In the next reversal, the poem adds, “there were bees back then,” and then flops back down like a punished dog with this monostich, “And then all the bees were dead.”

Within Olzmann’s imagination is also a young child’s curiosity. In the final poem, “Conversion,” in which loss is a constant (“the earth has ice caps, / then one day it doesn’t.), there is also wonder:

. . . the way an envelope arrives; how we

still reach toward one another, how this correspondence

endures: one figure approaches your door with a satchel

full of sand, pigeon feathers, sorrows, and names.

—

Matthew Olzmann is the author of three collections of poems from Alice James Books: Mezzanines, which was selected for the Kundiman Prize, Contradictions in the Design, and Constellation Route. His writing has appeared in Best American Poetry, Kenyon Review, New England Review, Brevity and elsewhere. He’s been awarded fellowships from the Kresge Arts Foundation, the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference and the MacDowell Colony. Currently, he teaches at Dartmouth College and in the MFA Program for Writers at Warren Wilson College.

Risa Denenberg lives in Sequim, WA where she works as a nurse practitioner. She is a co-founder of Headmistress Press; curator at The Poetry Café Online; and the poetry reviews editor at River Mouth Review. Her most recent publication is Posthuman, finalist in the Floating Bridge 2020 chapbook competition.