First Lecture

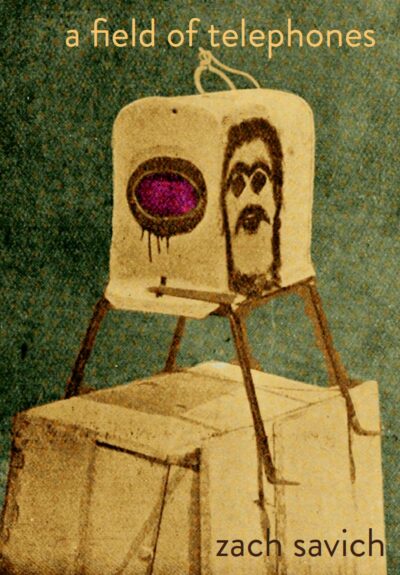

Author’s Note: The following is the start of the first “imaginary lecture” that appears in A Field of Telephones (53rd State Press, 2025). The lectures are about and around the legacy of the poet Theodore Roethke (1908-1963). I first met Roethke in an alley in Seattle, outside the Blue Moon Tavern. That’s where I first saw his name, I mean. It’s on a sign; maybe you’ve seen it—“Roethke Mews.” I didn’t know either word, so they stuck with me. A “mews” is just a little street, but it also works as a blurb: Roethke mewls, and moos, and muses, and meows. His legacy is all the sounds and places his poetry calls to. It rhymes toward us.

The book—which combines memoir and lectures and archival research and shaggy skits—is in the tradition of texts-for-performance that it’d probably be impossible to perform, though I hope we’ll try. And I’m not sure if an “imaginary lecture” remains “imaginary” once it’s printed, once you’ve imagined its performance. Its voice is that of a pseudo-scholar quixotically nostalgic for an era in which one could be a “Roethke man.” Like that could be enough. Like an English Department might tell you, during a job interview, “We used to have three Roethke men, so we’re relieved you applied. The Berryman men are getty huffy!” That’s silly, and nothing to be nostalgic for, really, but this voice (inspired in part by Jack Spicer’s lectures collected in The House That Jack Built) also earnestly believes poetry is enough, or can be. The things we care about might yet be enough. The setting is the Theodore Roethke House Museum in Saginaw, Michigan, kinda. A summer evening. A circle of chairs.

It’s hard to imagine a better setting for a week of lectures about Theodore Roethke. Can you hear me? “Roethke viewed the self as continually seeking a harmonious dialogue with all that is,” as Ralph J. Mills wrote. So that’s what we’ll go for tonight. Thanks to Betty Huff for adjusting the lights so that—when I turn like this—see, there’s Roethke’s profile. My hair is his nose, its shadow, and the clock on the mantle is his brow. The lectern’s his gut. Someone asked if I had an outline for the evening’s talk—there it is. That silhouette’s my outline. A full-body suit kinda shadow. What did they say his favorite meal was? Porterhouse steak, and a deep-dish martini.

(Laughter)

I know what you’re thinking. Anyone who’d be interested in a week of lectures about Theodore Roethke might be interested no matter what the setting is, but this one—living room of his childhood home—is pretty special. I love those fireplace tiles. I heard they found them in the attic a while ago. There’s that thought from André Breton, who you are is who you haunt. Roethke’s haunting us, as we haunt the place. Don’t think I won’t answer that antique phone and listen for him if it rings. I’ll tell him all my secrets until he talks.

I want to start with the question of legacy, the present.

Why Roethke, why now. As the mountain climber said, breathing out, “Because it was air.” Well, Roethke did write: “Loving, I use the air most lovingly. I breathe.” I wouldn’t mind being used like that. That line actually takes us to his student, Richard Hugo, following the drift of the word “air”—our game of telephone, this field of telephones. There’s that film of Hugo teaching, when he’s live-revising a student’s poem, and he focuses on this one line: “This is Methodist and there is no air.” The line is buried a bit in the student’s poem. But that’s the real start, he says. The engine turns over. The turnovers are delicious. The students are what you’d probably call co-eds, smoking cigarettes in class, Montana, the ’70s. I used to show that clip as a way to talk about what we wouldn’t do in a poetry workshop—mostly, we wouldn’t just have me go on and on about what their poems were actually about. Though the moment is interesting in a scholarly sense, or in the senses I prefer to call scholarly, because that line Hugo says is the real start? It sounds like a sound he was often listening toward, in his own poems. “This is Methodist and there is no air” sounds a lot like a line of his like, for example, “but that is auditory and will not do.” Can you hear that? A harmonic, ringing through. The real start, whenever it happens, should startle us.

Anyway, it’s a particular honor to think about legacy in this setting. “We must permit poetry to extend consciousness as far, as deeply, as particularly it can,” Roethke wrote. I mean “particular” in that sense—what can poetry and thinking about poetry particularly do? We see a lot happening with the fate of the humanities, the contemporary university. Questions of survival. Leveraging strategic utility. It can be pretty different from the fantasy we might have had about the university, about learning and the public good. But this site, what they’ve made of his childhood home, does so much for the public good. Legacy, here, is about more than preserving a reputation, a critical shrine. It’s about—all their work with kids, public health, mental health. Roethke suffered in those terms. But the terms were different then. They say his parents used to put up signs for whoever needed it, saying you could get a meal here. We all gather now in that spirit.

“Loving, I use the air most lovingly. I breathe,” he said. So, let’s err on the side of air, in these talks. What Stein said about Sacramento—“there’s no there there”—might be better, especially for Stein’s poetics, as “there’s no air air.” A step away from “aye aye.” “The highest minds of the world have never ceased to explore double meanings,” as Emerson said, at least twice. Who’s he calling high? Roethke would agree, said a poet’s “someone who is never satisfied with saying one thing at a time.” As if you ever could.

But speaking of double meanings, Roethke does say in one poem: “Light airs! Light airs!” We’ll talk about his repetitions later. “Most poets have only a handful of ideas; the best, it seems, have fewer,” Luke Brekke wrote. Roethke showed how few ideas he had by repeating them? Maybe. He had “a minimum of ‘ideas,’ a maximum of ‘intuitions,’” as Kenneth Burke said. Anyway, in “Light airs! Light airs!” you’d be right to hear “airs” as “errors,” maybe, but it’s better to hear “light airs” as an elemental compound. “Airs” comes through initially as a noun, in my doubled hearing, I do have two ears after all, two “errors”—that is, we might hear “light airs” as a reference to the airs that are light. And then we’ll hear its secondary register, as a verb. Light airs itself out. But air is complicated, just ask a lung. Especially for a poet with Roethke’s relationship to gusts: somewhere he says he “scratched the wind with a stick,” a wind that “sharpened itself on a rock.” Careful you don’t cut yourself on that wind. So, he’s in the air, is all I mean, especially here, and it’s a very particular air. It’s made of piano scales and exhaust from Gratiot Avenue and residues of cosmic junk, an old laceless shoe along the road, quasads or—

AUDIENCE: Quasi-stars.

Something like that. “Was it dust I was kissing,” he says somewhere. Which some critics have said is about a dusty mummy or something, a ghost, but I think it’s right to hear it as a beam of dust in kitchen light. Right at child-level. Give it a kiss. And remember kissing, for Roethke, is often about creating complex circuits that surge and then burst, from solitary to something solitary-and-something-else: “My lips pressed upon stone,” “My own tongue kissed / My lips awake.” “Is circularity such a shame?” he asks. I know there are a lot of actual scholars here tonight and many more watching from home (makes tight-frame thumbs up gestures and waves for the camera) who know a lot more about this, but, anyway, I’ll start off tonight blowing some kisses toward the question of Roethke’s legacy. At the time of his death, the question of his legacy being a question might’ve surprised some people. He’d won all the awards, been one of the teachers of his day. Lauded as “the father of the next generation of poets,” for his roving engagement with “deep imagery, confessionalism, neo-surrealism, and the return to a kind of pastoral ecstasy” end-quote.

AUDIENCE: Who’s that from?

I can share notes later. Anyway, that variety has made him hard to pigeonhole, but it’s partly why he was such a good poet for me to encounter early, in my own college sweaters. I mean, I was pretty sweaty. He’s an anthology. You can open to any page, see something else. That “next generation” that he’s the “father” of is commonly thought to mean his students—Hugo, of course, and James Wright, Carolyn Kizer, Tess Gallagher, David Wagoner—but it goes further. Tomorrow night I’ll focus on that. And also on where his legacy doesn’t go. That is, it really doesn’t go to the kind of prosaic, epiphanic free verse tiny-tidy narrative monologue essayistic dioramas popularized in the 1980s as a backlash against modernism, a bulwark against postmodernism. A mode of poetry that is still, sadly, often assumed or insisted on as a kind of normative neutral centrist position in a lot of poetry circles. Sad little skits of wisdom, highlighting the poet’s sensitive sensibility and special knowledge. A view of poetry that leaves out most of poetry, let alone people. So many views of poetry leave out most of poetry, let alone people. Those poems should let people alone even more. You know the kind of poem I mean. There’s a grabby first line, a theme the speaker worries, with aching control. Vamping through tone. Look at me. They’re a little sad, a little suburban, a little knowing. Deep thoughts about Vermeer and weather and a figure from pop culture, whose work is usually more interesting than the poem, maybe jazz. The snacks of childhood. Sticky table after school. A stickiness that’s pretty dif- ferent from the diaphanous lacquers in Roethke, what Burke called “the curative element of primeval slime.” Then there’s a conclusion that rings like truth, but it isn’t anything you wouldn’t know already, tiredly. “School of Quietude,” some used to call it. Ron Silliman, mostly, in his blog, talking about the “School of Quietude.” A school marked by its denial of being a school. Wanting to be the “unmarked case,” exempt from aesthetics. Poems that might take as their subject, as William Matthews said, experiences like, “I went out into the woods today, and it made me feel, you know, sort of religious.” I pre- fer “quietus” to “quietude.” Quietus speaks of death. Like we have some friends in Cleveland who have this neighbor who throws rotting vegetables over the fence, cans of beans, stale bread, sometimes like half a leftover casserole, little wads of foil? It’s something the church has them do, a good deed. That’s quietus. Well, it could be, it could be about death, especially if you ate all those casseroles, warm from the grass. An aesthetics not of wallpaper, but of things coming over the fence, more like William Morris when—

AUDIENCE: Brad, is that the same William Morris as the agency?

I don’t think so. “Ask the mole,” as Roethke said. I mean the artist, designer. Textiles. Poet, too. 19th century. Maybe you mean William Morrow? That’s a literary agency, right?

AUDIENCE: No, William Morris, the agency. Here in town. Is that who you mean? I think it was also the 19th century, or close enough. Let me look. (Spends time with phone.) Yes. It started in 1898, in Hollywood—

Well, it’s all just one step away. Things thrown over the fence. Words for the wind. All my friends and I used to go by the name Ed Bedford. Every word rhymes, when your ears are plugged right. Anyway, Matthews says these poems sound like, “I went out into the woods today, and it made me feel, you know, sort of religious.” But Roethke’s feelings were far from “sort of.” His interiority was loud. Roar if you want. But because of his affiliation with an official verse culture of his day, and his desire to be a tennis star, then a coach, and to get acclaim from those who labor as maître d’s at the table of the greatly great, critics who obsessed over whether or not Roethke was, say, the “strongest survivor” of the “middle generation of American poets”—because of all that, he’s probably more often thought of alongside poets like Robert Lowell and Richard Wilbur than with the experimental movements that, as I’ll get into in a bit, his work is actually closer to. Never mind what a useless phrase “experimental” is. I’m with Stevens: all poetry is experimental, though I’m mostly with myself—it’d be better if we just said experiential. A poem either offers a real experience of experience or it doesn’t. That’s basically what Rukeyser says. We know what we mean by real. Or it will show us, in time. The real poem becomes true. Or did.