Allusion & Correspondence: On Translating Jorge Teillier

This essay serves as a translator’s note for four poems from Jorge Teillier translated by Mathew Weitman and published by Poetry Northwest.

Nostalgias

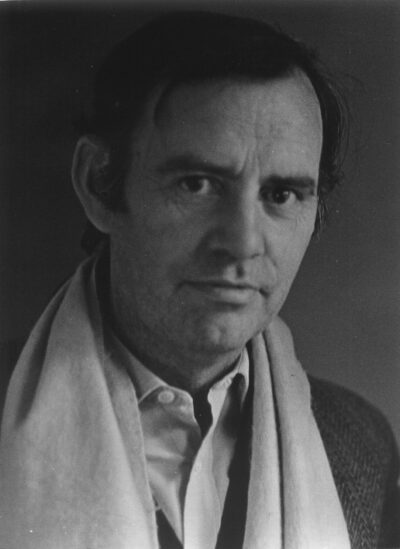

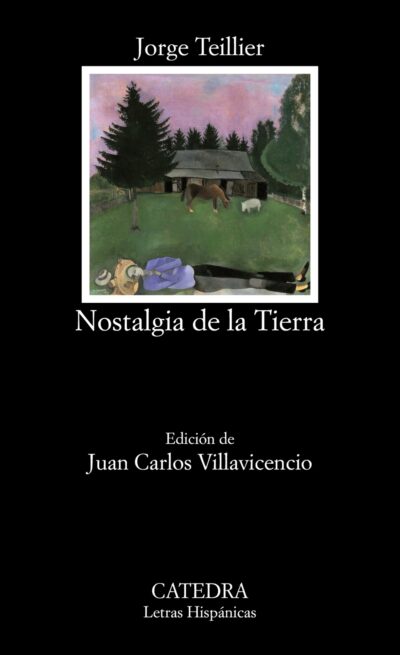

Born in 1935 in the rainy southern city of Lautaro, Chile, Jorge Teillier was the author of fourteen collections of poetry in a career spanning forty years. While a brief internet search might assert that Jorge Teillier is one of the most “influential and important Chilean poets of his day,” it is only with the 2013 Spanish language anthology, Jorge Teillier: Nostalgia de la Tierra, that one can fully encounter the sweeping breadth of his canon. Juan Carlos Villavicencio, the editor of this academic volume, has not only provided an invaluable introduction to Teillier’s life and work, but has also painstakingly collected, edited, and annotated the entirety of Teillier’s poetic output.

I do not use the word “painstakingly” lightly. Upon opening this glossy collection, readers are quickly gratified with the luxurious assault of an absurd number of footnotes. It is a truly remarkable feat (for both poet and editor) that nearly every poem has several allusions, a heavy dose of ekphrasis, or an obscure epigraph or dedication noted in the margin. When one tracks Villavicencio’s meticulous annotations throughout the book, one is also tracking Teillier’s increasing intertextuality. Moving chronologically through his oeuvre, one need not even read Spanish to see that in the final pages of this volume (before the extensive endnotes and index, of course), Villavicencio’s footnotes take up more space on the page than Teillier’s poems.

In my decision to translate Teillier’s most allusive, complex, and seemingly “untranslatable” poems, I have endeavored to bring forth the daunting constellation of references that are integral to (yet glaringly absent from) poems by Jorge Teillier currently available to English readers. With these four translations, I not only hope to bring Jorge Teillier’s most intertextual poems into the English language for the first time (with the exception of “El Retorno de Orfeo”), but also the remarkable scholarly work of Juan Carlos Villavicencio along with it.

Allusion: Intertext[ile/ual] Snagging

Somewhere in the second volume of Don Quixote, the agéd knight remarks, “Translating from one language to another, unless it is from Greek and Latin, the queens of all languages, is like looking at Flemish tapestries from the wrong side, for although the figures are visible, they are covered by threads that obscure them, and cannot be seen with the smoothness and color of the right side.” The humor here is of course embedded (embroidered?) in its metafiction: the novel’s conceit that it is itself a translation from Arabic. And while we can content ourselves with the several obvious explanations of what these pesky threads must be (the word in all its intricate and material parts—sound, sense, association, cultural implication, &c.), we might also ask “But what if these threads are not original—are instead borrowed, recycled, or stolen?” That is, how can—how should?—a translator translate that which is itself a translation, recapitulation, or appropriation?

The many threads of Jorge Teillier’s intertextual poetics present numerous productive points of impasse for a translator. Take for example Teillier’s poem “El Retorno de Orfeo” (“The Return of Orpheus”). This poem is dedicated to the Chilean poet Rosamel del Valle (1901-65) and includes an inexact quote from del Valle’s book El sol es un pájaro cautivo en el reloj (1963) in the final stanza: “«—Tu muerte o mi muerte—decías—será como el derrumbarse fortuito de una lámpara»”. However, Villavicencio also notes a less direct allusion in the final line of this poem: “«lejos de donde la luz pueda alcanzarte».” This unattributed quotation is a translation from Novalis (“Hinunter in der Erde Schoß / Weg aus des Lichtes Reichen”—which loosely translates to “Down into the Earth’s womb / Away from the realm of light”) used by del Valle as an epigraph to his collection El joven olvido (1949). As such, Teillier’s allusions to del Valle are allusions to del Valle’s allusions; his poem ends where del Valle’s work begins.

Jorge Teillier is not one to note his own allusions; and so, I found myself repeatedly failing in my endeavor to bring forth the intertextuality of Teillier’s poetics without sacrificing the grace of his lyric inventiveness. Translating and including Villavicencio’s footnotes felt like too much braiding, and yet to not account for them was to lose the thread completely. In A Manifesto for Ultratranslation, Jen Hofer and JD Pluecker write: “. . . failure is productive: a snag that makes the seams visible. Critiqueable. In failure there are moments of astonishment” (2). Teillier’s intertextuality indeed presented visible seams in the reversed tapestries of my translations. I returned to these poems and looked even closer at Villavicencio’s marginalia, allowing my failure to astonish me. In the case of “Pequiña Confesión,” I was immediately drawn to the typographical incongruity of English proper nouns (such as “Fort Collins” and “Doc Holliday”) contained by the less familiar double arrows of Villavicencio’s comillas; they snagged. And so, I decided to pull on these snags as much as I possibly could without unraveling the poems.

In these translations, I have “un-translated” Teillier’s allusions, returning them to their original languages in various ways. In my translation of “El Retorno de Orfeo” I have placed Novalis’s German at the top of the page and translated Teillier’s translation of del Valle’s translation in the final lines, with the objective of putting all three poets in conversation with one another. This is not to say that I am prioritizing English or German as I return Teillier’s allusions and translations to their source languages, nor is this a way of “correcting” Teillier’s conscious artistic decisions. Instead, in the cases of these “un-translations,” I am attempting to avoid an allusion getting lost in yet another “inexact” translation, in addition to uncovering the expanse of Teillier’s reading. These moments of “un-translation” are my humble attempts at achieving the goals outlined in A Manifesto for Ultratranslation. There are several domesticizing gestures that I hope to undo with this project. In the case of “Pequiña confesión,” for example, while Villavicencio notes that the quoted “Es mejor morir de vino que de tedio” is an allusion to Mayakovsky, and—as expected—provides the original Russian text beside his more “literal” Spanish translation of the same quote, I have inserted Mayakovsky’s Russian directly into my translation of this poem.

Most importantly, the goal of these “un-translations” is to never deprioritize Spanish. Whenever possible, I have preserved as much of the Spanish language as sense might allow in an English translation. In the case of my translation of “Para Antonio Machado . . .” I have replaced Teillier’s allusions to Machado with Machado’s own words. As such, these Spanish fragments are no longer references to Machado’s work, but direct quotations from the poet. In all instances of this “un-translating,” I have maintained Teillier/Villavicencio’s comillas so that neither poet nor editor is ever lost in his own allusions, translations, and annotations.

Of course, in my quest to follow every thread in Teillier’s intertextual poetics, there was always the temptation to bring new allusions (from my own poetic tradition) into these translations. Even worse perhaps, there remained the distinct possibility of “finding” references in Teillier’s work that were not there. For example, when the speaker in “Pequiña Confesión” longs for the “music” of wagons on dirt roads, is it possible that Teillier has Basil Bunting’s “Briggflats” in mind? Probably not. But later in this poem, when the speaker says, “En medio del camino de la vida,” Villavicencio does not note that this is clearly a reference to Dante’s opening lines of Inferno. Has Villavicencio overlooked this reference, or does he merely think it is so obvious it goes without saying? Can either of these possibilities exist for “Briggflats?” In this case, I have elected to return Dante’s oft-quoted line to its original Italian and abandoned the more obscure possibility of Bunting’s oxcart-erotica.

To return then, briefly, to Cervantes’s tapestry metaphor, it goes without saying that these translations not only proudly display Teillier’s poems from the wrong side, but also aim to showcase the frayed threads that snagged in the transportation of these highly allusive works from language to language. In so doing, it is my hope that readers will not only follow these threads into the vaster patchwork of intertextual poetics, but also admire the craftsmanship and artistry of Teillier’s weaving.