Interview// “On Hearing Silences from Afar and Getting Close”: A Conversation with Elizabeth Bradfield

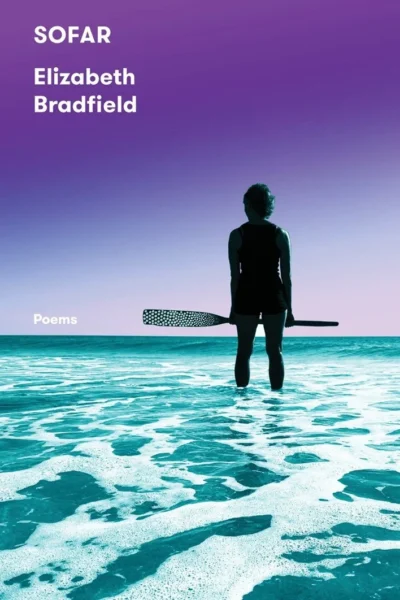

Elizabeth Bradfield’s sixth poetry collection, SOFAR (Persea Books, 2025), bears a title that is an acronym for the “sound frequency and ranging channel,” a deep layer of oceanic water that enables sound to travel vast distances. I first met Elizabeth at the Skagit River Poetry Festival in 2024, when she was here promoting Cascadia Field Guide: Art, Ecology, Poetry, a book she co-created for Mountaineers Books. I was able to talk with her the day before SOFAR‘s release, zooming from Cape Cod, where she lives full-time, to my home in a coastal farming valley of Washington.

*

Jessica Gigot (JG): As a farmer and gardener, I am very much a land person. I lose my bearings on water. In SOFAR, I learned a lot about being on boats through the speaker’s experience working on or near water. How has this work influenced your writing and how did this collection come together?

Elizabeth Bradfield (EB): My last individually authored collection, Toward Antarctica, came out in 2020 and that was a more project-driven book about working as a guide on Antarctic expedition trips. When I started pulling poems together for this manuscript and thinking of it as a collection, I found there were a lot of poems about ecological grief, desire, the body in menopause, and a long-term relationship—many of them exploring these subjects through the metaphor of parts of boats (chock, hawse, bell, etc.). I’ve also been really obsessed with the idea of the sound frequency and ranging channel, this layer of water in the ocean that permits strange listening. Through the SOFAR channel, sound bounces along like light in a fiber optic cable and can travel across entire ocean basins. If the conditions are right, for example, a fin whale off the coast of Massachusetts can hear another fin whale off the coast of Portugal. The book started to cohere around the idea of listening across distances—between species, geographies, moments in time, and humans who are in some way uneasy with each other.

Working on boats, or being on the water, has been part of my life since I was a kid growing up in Tacoma on Commencement Bay. I worked on Seattle’s Argosy boats during college at the University of Washington, then as a deckhand right out of college, signing on with ecotour boats up in Southeast Alaska and down in Mexico. It was really important work for me to figure out who I was in the world. In the pandemic, I stopped working on the “expedition boats” that run multi-day natural history ecotours. The industry shut down, and also I had become uncomfortable, in many ways, with the impacts I was seeing of that work. It was a real wrangling for me and I miss that community and work, as much as I feel the decision to stop was right for me.

JG: The poem “Origin Story: Re-Wrought,” which first appeared in Northwest Review, felt like a touchstone for the collection. What do you mean by “unbodied” and how does that relate to your process of self-discovery and relationship with the natural world?

EB: I lived so much in my head all through college, but when I’m on boats, I’m there for the moment: I’m looking at the water, I’m paying attention to the weather. As a student, I thought about a lot of things and I had a lot of theories and ideas, but I wasn’t living a physical life. I was all in my head and, thus, “unbodied.” Or I thought I was. I didn’t understand even how deeply I was disconnected from my physical self until my six-month contract living and working onboard a small boat in Alaska. Almost immediately upon arriving via plane in Ketchikan, I was put to work cleaning the deck, and I found that my mind was free to do things in the background as my body moved. It was a sensuous experience in some ways. On the boat, I also fell in love for the first time, so all of these things outside of books and in my body were happening. The world I could feel and observe beyond me came into focus, and that includes the more-than-human world. Glaciers, bears, whales, puffins, nudibranchs, kelp, fireweed, islands, spruce—the whole of the temperate rainforest that surrounded me—and the love and care for engaging and knowing that place as the naturalists aboard the ship demonstrated to me. I saw a new way of being, and I wanted to be part of it. I felt myself a body in the world, in a community of bodies. Not just thinking and exchanging ideas, but breathing and looking and living together.

JG: To touch on other themes of the book, there is a continual reference to a relationship. Specific lines have stuck with me, like in “Tender” you write “even as we drift” and in “List” you talk about “holding our edges.” It seems like you are exploring how to remain oneself while having this shared experience of a life together. There are also several references to aging and an acceptance of change. “Erratic,” first published in the Alaska Quarterly Review, is a poem I felt deeply as a middle-aged woman going through the early stages of perimenopause. Was it a conscious decision to write about love and aging?

EB: I wouldn’t say it was a conscious decision. It’s the soup I swim in, you know what I mean? I’ve been with my partner for a long time. She and I will celebrate our 30th anniversary this fall. I was a baby when we got together—I was twenty four for crying out loud. A lot has changed in that time. Now I’ve just gone through menopause, and the shifts, emotionally and physically, have reverberated through my emotional life, my interior life, and my relationship. They’ve been seismic. And it’s not so much the hot flashes. I don’t care about that stuff. I get a little sweaty, whatever. Emotionally, it was really hard for me. I felt like an insecure, out of control, sensitive hair-trigger bundle again, like I was when I was thirteen. No one told me to expect to feel this raw. It really caught me off guard.

I am so grateful to have shared a life with somebody over all these years. I love my partner more than anybody. She knows me better than anybody, yet I mourn some of the changes between us over those years. It’s not always easy. I think poetry is a place where I want to be really honest. And if I’m honest with the things that are occupying me internally and the things that come across my horizon externally, if I’m honest about how those things make sense of each other, then they’re going to show up in my poems. I wouldn’t say it’s deliberate, but I think it’s inescapable.

JG: It seems like we’re in a bit of a cultural shift where more writers are taking on these biological and emotional shifts, unique to female bodies, as subject matter. I’m curious if there are any writers or people you’ve read that have inspired you to write about your experience?

EB: When I open these conversations with friends, they’re like, “Oh, yeah, let me tell you,” but it’s rarely been at their initiation. Nobody says anything, unless I ask. Those silences are really harmful. I respect people’s need for privacy, because perimenopause feels vulnerable, but I also feel angry. Three weeks ago I read a headline celebrating, “The End of Menopause,” or something like that. Is that really our cultural solution? To engineer this huge life change away? Maybe we have it for a reason and maybe there’s some strengths that we can find in our experience of navigating the shift, surviving it, and seeing what happens when we come through on the other side. Now that I think about it, there are parallels between coming out as queer when I was nineteen and the exposure of this other, incredibly private and incredibly significant, experience and identity.

I read All Fours. I thought it was funny, but it didn’t rock my world. When I started writing these poems I was speaking into a silence, which is something that drove me to write them. Those silences have motivated my writing before, particularly in my first book, Interpretive Work, which has a series of odes to butch women. At the time, I felt like there were a lot of queer poems in the world, but not a lot of poems celebrating butch women, and I wanted to challenge that.

Gabrielle Calvocoressi’s works, especially in Rocket Fantastic, were influential. I really love the ways that Gabby’s poems are vulnerable and strange and a celebration of the self, including the grief a body can hold. I have always been interested in socializing the nature poem. What I notice in the world around me is totally tied to what’s happening in my personal life.

JG: I love the idea of “socializing the nature poem.” I feel like that’s something I’m struggling with because I write both poetry and memoir. Even as someone who has a science background, I find myself much more inclined to read those stories than a wonderfully written nature book. SOFAR feels like a sort of environmental memoir to me.

EB: It’s flattering to know that you think of this as an environmental memoir. I was talking with a colleague of mine and she was describing the poems as enacting a kind of eco-intimacy and I think those two ideas are not dissimilar. I’m so glad readers like you and my colleague see that in the poems.

I’ve been very lucky that I’ve been able to build a relationship over time with this place where I live now, Cape Cod, and with individual whales in particular, definitely with the seasons of this place. That’s something that’s important to me as a naturalist and also important to me just as a human. The other day, I got to hang out with Nile. She’s a humpback whale that I’ve known the past twenty-eight years. I love her. She’s such a weirdo. I know that I’ve been very privileged to build relationships with individual whales—can I call it a relationship when she is not aware of me? I hope that by talking about and trying to share some of the nuances of those ties, including research, conversations with biologists, and lived experiences, maybe I can share a way of living that other people might be curious about. What does it mean to pay a little bit more attention? What does it mean to get a little closer? To feel yourself in relation to another being that is not human?

JG: Do you feel like this is one of your more intimate collections of work? You traverse and share a lot of your life with the reader.

EB: Grief is in this book, which maybe makes it feel more intimate. Also, I think I’m more comfortable as I get older with admitting how much I don’t know, how wrong I get things. Some of the book’s intimacy comes from those vulnerable aspects of the book, that kind of rearview mirror questioning. If you’re lucky, you live long enough to make a lot of mistakes—and they’re interesting. Mistakes are interesting. Why do we make them? What’s behind them? Is it just a fumble or is it coming from some kind of deeply held, preconceived notion that needs challenging? I think those questions are an undercurrent in SOFAR. Also, the ecological crisis that we’re living in is heartbreaking and scary. This book tries to hold that grappling, and that is intimate work, too.

JG: The poem “Plastic: A Personal History,” (published first in Poetry and then The Sun) ventures into the realm of ecological guilt. As a poet, how do you reconcile with climate change and environmental degradation? How is poetry, as a genre, helpful (or not) in processing environmental change?

EB: Sometimes my only response to things that are devastating is bitter humor. I think it’s a queer sensibility to laugh and make fun—think of the aesthetics of camp and a lot of drag, the long tradition of wry, queer (“gay” might be more accurate, historically) wit made most famous by Oscar Wilde—that’s the aesthetic behind the plastic poem. In response to something so awful, my best response, which is a queer response, is to look at how ridiculous the pervasiveness of this material is.

JG: You’ve spent a lot of time with work from nature writers around the country as part of co-creating the Cascadia Field Guide. How do you feel about the term “nature writing” as it describes your work and the work of other contemporary poets?

EB: I was on a panel with Camille Dungy once and she said, “I love calling it nature poetry” in response to a question about the term, wondering if it was too exclusionary or exclusive historically. Yes! Let’s just expand how we see nature poetry, who we see as writing nature poetry, what it can address, which spaces it can engage. Nature poetry has a lot of baggage. This is why that conversation with Camille was so funny. She’s like, “Yeah, let’s use it. Let’s just change what it means.” I really appreciated that perspective. What I don’t like about the term “nature poetry” in particular is that it often implies a naivete, a softness. And that’s seen as a weakness. I think about the ways that people talk about Mary Oliver, dismissing her poems as simple. I disagree. I think she’s an amazing writer. There is so much of her work that is very deliberately reaching toward praise and pushing against dismissiveness and toward connection. Is that soft? Or is that a demonstration of persistent and deliberate strength?

If someone says, “Liz Bradfield is a nature poet,” I feel like it erases or smooths any prickliness that my poems might have. And I’m pretty prickly. It’s like calling me a “nice lady.” Niceness is lovely, but somehow that label erases humor. It erases camp. I think it erases queerness. It’s a tidy category, and I like things to be messy. David Gessner advocates for “less scat, more shit” in nature writing, and I agree. I mean, let it be dirty. So I’ll take the term if people want to call me a nature writer or nature poet, but I hope they include my dirtiest poems. Or my gayest poems. Or my meanest poems when they use that term, not just the sweet, earnest, yearning, praiseful poems.

JG: The term “ecopoet” is a little bit more informed by environmental crisis or climate change, and is also limited, but it implies being informed by environmental issues.

EB: Who isn’t an ecopoet at this point? That term is so capacious, which I love; it also feels a little technical. I don’t know. . . whatever, just write the poems. That’s what I want to do. I want to write what’s true and real and stunning and utterly perplexing to me.

JG: Going forward, are you working on something new?

EB: I’m working with a couple of collaborators, Ian Ramsey, the author of Hackable Animal, and Samaa Abdurraqib, whose first chapbook, Towards a Retreat, was just recently published by Diode Editions. Ian, Samaa, and I are working on a Cascadia Field Guide-like book for this bioregion. They live up in Maine, and we are focusing on the watersheds from Cape Cod up to Nova Scotia, the rivers that flow into what is called the Gulf of Maine. We turned in the manuscript to the publisher this summer, so that has occupied a lot of my writing self recently. Now I’m trying to, at last, get some momentum on this project that I’ve been wanting to work on and have been holding in the background of my mind.