Linda Andrews: “While the Rest of us Slept – Kathleen Flenniken’s Poetry of Witness”

Plume

Plume

Kathleen Flenniken

University of Washington Press, 2012

—

In the Fall of 2013, Kathleen Flenniken was awarded the Washington State Book Award for Plume.

—

Where I live, in eastern Washington State, I frequently see evidence of the legacy of the Hanford nuclear site—in ads for homecare services designed for Hanford nuclear workers, on Richland High School’s “home of the bombers” mushroom cloud jerseys, and at the Tri-Cities airport’s “Three-Eyed Fish Café,” which alludes comically to deformed fish caught in the nearby Columbia River. A waste management company near Richland has applied to the federal government for a permit to truck up to 500 tons of Mexican radioactive waste over interstate highways for incineration at Hanford and transport back to Mexico. The reactor that John F. Kennedy dedicated in 1963 has been licensed to produce electricity through 2043. At the same time, Hanford receives massive federal funding as “the world’s largest environmental cleanup project.”

In Plume, her second full-length poetry collection, Washington State Poet Laureate Kathleen Flenniken opens a view into Hanford’s complex history, and— soberingly— shows how what is begun in one generation (scientific ambition, patriotic fervor born of desperate circumstances, the need for secrecy) continuously comes to fruition in the next. Her book is remarkable in its scope and stunning in its use of many poetic forms, including free verse, prose poems, slant rhyme couplets, call and response, and even redacted official documents and historical transcripts. This bold engagement with a variety of styles allows the poems to ricochet and resonate on the page as the poet’s understanding of her past life deepens, drawing the reader into an ever more complex web of personal memory and national history.

Indeed, the book moves through the material of memory with subtlety and surprise. Just two months before his assassination, President John F. Kennedy reaches with a radioactive wand and remotely starts the groundbreaking machinery for the ninth reactor at the Hanford Nuclear Reservation in Richland, Washington. Kathleen Flenniken is there, a child on the shoulders of her chemist father. In “My Earliest Memory Preserved on Film,” she says “I click play again and again.” (YouTube will take you there, too, to the “sea of crisp white shirts” of the assembled Hanford workers. Dial up the video and watch JFK ignite this book.) As Plume reaches into our national memory, Flenniken becomes a poet of witness to events critical to our state and the world.

Flenniken’s collection is the product of her durable childhood memories, her continuing connection to the Hanford community, and her crisp scientific mind. She first witnessed Hanford’s atomic legacy as a child of parents devoted to the industry. She herself studied civil engineering at Washington State University, and returned to work at Hanford for three years as a hydrologist. When she left, she headed to Seattle and further study (MS in Engineering; MFA in Poetry). What we get from her, then, in careful poetic progression, is her elegant attempt to bridge a divided self. In lecture, Flenniken has described some of the vivid contrasts she lives—as engineer and poet, as dweller in sagebrush of eastern Washington and tall trees of western Washington, as proud daughter of a nuclear chemist and grieving adult that the ground she grew up on was not what she thought. The book too exhibits these contrasts to remarkable effect—revealing a self at once attached to and divided from its native soil.

The historical facts are these: In the 14 months between April 1943 and July 1944, some 1,200 buildings were erected in Richland, Washington for the more than 51,000 workers assembled to produce plutonium to fuel the atomic bombs of the Manhattan Project. Virtually none knew the purpose for the material being produced at Hanford, except that it was for the war effort. Only after the bombs fell on Hiroshima and Nagasaki did the Hanford site become connected to the word “plutonium,” but the shroud of secrecy that covered Hanford’s work and purpose continued through the Cold War, when Flenniken’s father worked there.

That idea of secrecy for an unknown reason permeates Plume. Flenniken writes in “Whole-Body Counter, Marcus Whitman Elementary” how she and her classmates were tested each year for radiation contamination while thinking that all American school children did the same patriotic thing:

We were told to close our eyes.

Everyone was school age now, our

kindergarten teacher reminded us,

old enough to follow directions

and do a little for our country.

The image of children closing their eyes and doing as they are told in order to be tested for contamination is chilling. Flenniken’s quiet tone increases the reader’s sense of threat, a threat unacknowledged by their parents at the time. There is evidence in the historical record that Hanford workers had an understanding that their work held danger—though the nature and extent of the danger was not fully known for decades.

So while the children did their patriotic best, their fathers went off to work, taken by bus every day into the controlled- access area. Some of the fathers worked too closely with the plutonium. In “Bedroom Community,” Kathleen remembers:

We pulled up our covers

while our overburdened fathers

dragged home to fix a drink,

and some of them grew sick—

Carolyn, your father’s marrow

testified. Whistles from the train,

the buses came, our fathers left.

Oh Carolyn—while the rest of us slept.

Again we see the personal consequences of the meticulous scientific work that kept each individual worker from full knowledge of the entire undertaking. Flenniken’s approach to revelation is subtle. The “whistles from the train” seem like a signal that something is coming for these men. And her acknowledgement that “the rest of us slept” shows that they were all kept in the dark.

In The Witness of Poetry, Czeslaw Milosz notes “the peculiar fusion of the individual and the historical […] which means that events burdening a whole community are perceived by a poet as touching him in a most personal manner […] in other words, everything that connects the time assigned to one human life with the time of all humanity.” Flenniken’s Plume springs from a particular historical moment and shows how the secrecy necessitated by the creation of the atomic bomb did in fact burden a whole community of scientists and workers and their families. With the death of her friend’s father, the historical entanglement became a personal grief, and Flenniken’s unflinching poetry makes it so for us as well. Wherever we live, the decades-long failure to clean up the Hanford site has continuing consequence for the environment that “connects the time assigned to one human life with the time of all humanity.”

Flenniken’s “peculiar fusion” with the Hanford community is revealed in poems that run the spectrum from abstract to concrete, from physical to ethereal, from romantic to threatening. As acts of memory and witness, the poems move between the visible—such as the slugs of plutonium that are about the size and heft of rolls of quarters—and the invisible, like the measureable gamma-ray-emitting radionuclides. She recalls the mosquito truck spraying DDT, and we feel the cool danger as the children run through the “sweet-smelling chemical cloud.” When as exuberant children Kathleen and Carolyn catch snowflakes on their tongues, we want to stop them, save them from the invisible harm in that childish act. In “Rattlesnake Mountain” she writes:

I understand

what beautiful ghost rises up in the distance

in my dreams.

So the tangible mountain becomes the ghost of secrecy and, even less tangibly, inhabits a dream. That ghost appears again as several of Flenniken’s poems redact official documents into verse to reveal what double- spoken messages lurk in government speech.

Flenniken’s multivalent view of history shows itself in “Herb Parker Feels Like Dancing,” where the romantic mingles with the menacing. Here the severe, pencil-skirted women of the resource-starved 1940s have become the plentiful, big-skirted, nylon-wearing women of the 1950s. It was the era of the Cold War, yes, but there was fabric and fuel, and Herb Parker, the overall manager for the Hanford Laboratories, wanted to dance. Flenniken blends “That Old Black Magic” and other song lyrics of the day with power and strut as Parker embodies the lure and danger inherent in secrecy:

Don’t you understand? Someone

must step forward and play God.

How much better that the man

can lead? hold you tight

in his very good hands, and spin.

Plume’s epigraph comes from the story of Midas in Bulfinch’s Mythology. Midas had a secret, but finding it hard to keep, he whispered the secret into a hole in the earth. From that patch of ground sprang reeds that rustled the secret in every breeze. Similarly, Hanford’s poison was intended to remain in underground tanks, but it moves inexorably toward the Columbia River. Today radioactive fluids seep from the aged tanks and filter toward the water table. The dangerous secrecy that still pervades the nuclear industry is made visible in Kathleen’s poems, even as her imagery spins toward invisibility. For instance, in the title poem, “Plume,” watch her chosen image disappear: “like anything/ with a destiny/ a flock of birds/ sperm/ breath/ it will move/ downstream/ to the river/ yes the river/ will take it in.” This dispersal of the image implicates all of us in the impact of environmental degradation.

“Plume” shows, in form, how secrecy and corruption percolate. The poem is written in the shape of a soil column, with white spaces at its core to represent the contaminated ground water of Hanford gravitating toward the Columbia River. Such concrete and secret news is at the core of this book whose attentive forms materialize memory and tragedy as we read. As Flenniken’s poems seep down the page, we see in the trickle and drift of contaminants, and in the “permeable” and “impermeable” language of science, how “this 50 year old mistake” is still on the move. And how a book of poems can make us feel history in the most personal terms.

—

Linda Andrews‘ poetry has appeared in numerous periodicals, including CutBank, Nimrod, Seattle Review, Calyx, and Willow Springs. She has been awarded the Richard Blessing Award, an Academy of American Poets Prize, as well as a fellowship to the Ucross Foundation. Her book, Escape of the Bird Women, received a Washington State Governor’s Award. She is also the recipient of an Artist Trust fellowship.

—

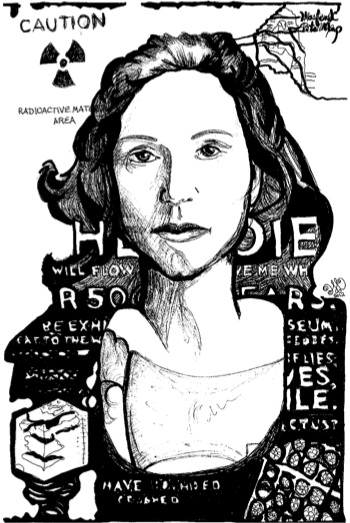

art by Holly Mattie

—

This review first appeared in the Fall & Winter 2012-2013 issue of Poetry Northwest.

Also available: Kathleen Flenniken’s “Augean Suite,” from Plume.