Interview // “Rewriting the Sky”: A Conversation with Monica Ong

Monica Ong’s poetry first presented itself to me in the form of “The Vessel,” and by presented I mean it came as an omen. This poem led me to her first collection, Silent Anatomies, selected by Joy Harjo as winner of the Kore Press First Book Award. The visual expression of her poems held the force of a planetary conjunction or Jungian synchronicity. They prefigured ideas I had been wrestling with but couldn’t yet envision clearly: shame’s relationship with silence, implied-yet-absent hearts, degrading familial bodies, and the urgent yearning to form collateral vessels—to reach beyond the body’s impenetrable blockages with the hope of finding alternate means of connection and nourishment.

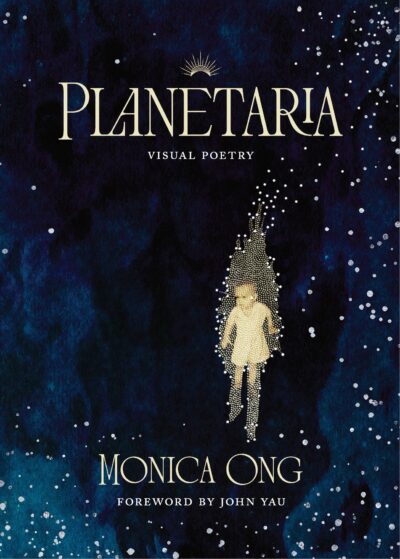

A shift from inner to outer space, Planetaria (Proxima Vera, 2025) explores the intimate galaxies contained within us, particularly in the celestial bodies of women. Alternating perspectives—telescopic to microscopic—expands passing moments of sensual pleasure and private family histories into areas of study worthy of close analysis.

As a light sleeper and troubled sleeper, both of which have intensified in middle age, Ong’s collaged Insomnia poems felt richly relatable, especially at 2:46 a.m. She washes these text-and-image dreamscapes with spectral hues of lavender and amber, indigo and jade. Within curvilinear shapes, loneliness unspools its secrets while desire and fear yearn for reconciliation and rest. A microcosm within the collection, these collaged poems open possibilities of space: ecotones between the living and the dead, waking and dreaming, ancestors and progeny, the rational and the lyric. Planetaria’s hybrid poetics prove that human consciousness is its own universe; to understand this vast landscape of inner/outer space requires many and myriad maps.

I had the good fortune of corresponding with Monica Ong about the imprint of women in our lives and her approach to disrupting the inherited systems we take for granted as “the industry” and “the canon,” which is to say, the illusion that what currently exists leads to the inevitable.

*

Gabriela Denise Frank (GDF): Monica, I’m delighted to be in conversation with you about this book! You’ve said that your projects often begin with a steady line of inquiry; how did the continuum unfold from Silent Anatomies (inner space) to Planetaria (outer space)?

Monica Ong (MO): Reflecting upon this continuum from inner space to outer space, I often find myself drawn to questions around hidden histories and how visual poetry can draw out these narratives while also noticing the tension between what is seen and unseen. While Silent Anatomies interrogates cultural silences of the body, Planetaria wonders what stories would come to light if we were to rewrite the sky from a female perspective.

My gaze shifted from looking into the past toward my elders’ stories in the first book towards a more future-forward direction that is in conversation with my son’s generation. Now, I’m thinking together with him on how to negotiate these complex histories as we navigate a way forward together in uncertain times.

GDF: Your compelling visual poetics, which interweave art and science, raise questions about truth versus fact versus data. Is a technical diagram or research paper more factual than a family story or document? I’m thinking of the line, “The problem with numbers that count our deaths is they don’t carry the smell of moss.”

MO: Spending time in the information design space made me curious about how the aesthetics of data within a textbook context could frame poems that interrogate the locus of power and authority in the narratives of working motherhood, gender, and cultural “rules” around a woman’s place in the world.

In my own messy reality as a young mother, I struggled with unrealistic societal expectations and glaring inequities, my body mangled by burnout and insomnia. I felt exhausted by what seemed at the time to be a losing battle. You could say these poems were an attempt to rewrite that textbook so that I could navigate this precarious territory with attention to overlooked experiences and invisible labor. I was seeking an expansive way of seeing each other as more than numbers and data points, but intrinsically unique and precious.

GDF: What does a visual or hybrid approach to poetry offer that narrative alone does not?

MO: What I like about this way of making work is its spirit of invitation. More audiences get invited into the room when they can engage with poetry in playful and unexpected ways. It’s another way to ask readers to slow down for a closer reading. The formal choices are deliberate in not only holding but sustaining attention when unpacking layered ideas. It’s natural that, as technologies change, new literacies emerge that blur boundaries of form and genre. They give us an opportunity to enact new alchemies of expression where each element mutually heightens the overall effect of the whole experience.

GDF: Do you tend to begin poems with text and then illustration follows, or are you drawn first to shapes, colors, and forms from which poems grow?

MO: I’ve made work from varying points of origin, whether by chancing upon interesting forms that spoke to me as compelling poetic forms or generating writing and letting its images, sensations, movements, and associations lead me to design decisions that can amplify their conceits. Early in my process, I do a lot of gathering—looking, free writing, going to flea markets, visiting museums, making lists, collecting objects, whatever research helps me open up my questions. When a spark occurs between elements, I listen carefully to what it’s asking of me and then align the lyrical elements, layouts, visual vocabularies, and materials in a way that translates into a memorable experience of poetry.

While learning to cut my child’s hair during the pandemic, I based “Who Will Give You Haircuts on Mars” on recalling the shape of my hair on the floor of my mother’s salon when I was a child, noticing how it was echoed in a diagram I’d found about the surface of Mars. Collaging disparate elements together tends to open a portal from which I write and allow the tension of these polarities to create heat.

GDF: You’ve said, “Poems are an attempt to break shame’s collective spell so that we can see each other.” I wonder if this is linked to the urge to diagram ideas atomically for the purpose of study.

MO: Shame figured so much into my early (and anxious) self-conception that my creative process also became a kind of laboratory for examining the inherited ideas I needed to unlearn in order to make space for new possibilities of being, mothering, making, and nurturing community.

GDF: That feels related to what you’ve said about hybrid practice, that it “challenged me to let go of attachments to systems and structures that no longer serve our growth.” How does this idea interact with “traditional” poetics—and science?

MO: The most valuable thing I have learned from scientists and designers is how they apply methods of experimentation to test hypotheses in practical reality and how vital it is to be brutally honest about the shifts in thinking required to arrive at better outcomes. Doing so means embracing failure as feedback for iterative learning, ideation, and testing. It also keeps us from forming attachments to constructs that may have been dominant for a while but may not necessarily be in service to our growth or the work we are trying to do. This is why my collection opens with the words of experimental physicist Chien-Shiung Wu who said, “The main stumbling block in the way of any progress is and always has been unimpeachable tradition.”

I found this approach to be really useful when starting out my career. It’s human to want to compare ourselves to others or to doubt ourselves because our metrics of success don’t look like another’s, especially in this obscure space. But what has sustained me is learning to work from a place of service and trusting that by sharing a deeply personal point of view in a new way, we make it easier for those seeking our work to find us. It keeps me from going along with things just because there’s a perception that it’s always been done that way since forever, which nothing ever is. By resisting the pull of comfort zones, formulas, or the desire for guaranteed outcomes, we can make room in the creative process for innovation and surprise.

GDF: Your Insomnia poems are extremely relatable to those of us awake in the middle of the night. Can you talk about the intersection of women, insomnia, and sleep? I’m intrigued by your architecture of colors: Jade Insomnia, Yellow Insomnia, Lavender Insomnia, Amber Insomnia…

MO: When I read My Private Property by Mary Ruefle I was struck by her many-colored spectrum of sadnesses throughout the collection. Thinking about my insomnia in this way allowed me to explore its many layers and landscapes, particularly when framed by geometrical diagrams of human consciousness by 19th century psychologist Benjamin Betts. I began with “Lavender Insomnia” since I was using lavender in my sleep therapies and liked how color easily stimulates visceral associations and sensations that begin to pulse through the poem. The Insomnia poems correspond to the range of colors that come from these diagrams and are collaged with family photographs of the ancestors I imagine wandering these interior spaces and with whom I am in conversation.

GDF: In “Amber Insomnia” a table is anchored by a bowl; in “Indigo Insomnia” a pile of brown paper packages are an avalanche of grievances; in “Jade Insomnia” mantras flood a graveyard’s silence. How do you stay grounded while writing poems in dreamlike spaces where the past seems intent on unmooring the present?

MO: Insomnia is a land that often feels opposed to dreaming, but even in that hellish place there’s an opportunity to face the things that scare us or keep us up at night with an eye for clues to help us puzzle through the maze of our doubts and disappointments. As I wrote, I was curious if I could transform my insomnia into a space of reconciliation, of staying in conversation with my discomforts and my ancestors until I no longer felt haunted but rooted. What I’ve learned to ask myself in the studio is a question that reliably pushes me to carefully tune that inner compass: What can I do to encourage just one person?

GDF: I admire the playful questioning in “Sun, Not Son” in which the speaker asks, “What does it mean to be a man?” What do you imagine is asking to be set free, as it relates to gender?

MO: What I liked about that experiment was the use of alteration to create a new frame of reference. The original diagram was describing the position of the earth in relation to the sun when viewing an eclipse. It made me think about how patriarchal paradigms of gender can tend to get in the way of seeing the humanity of those who don’t buy into conventional ideas of masculinity. Throughout the poem are images of circles broken or the shape of open-ended arcs, suggesting that these cycles are not fixed but up to us to disrupt or reimagine.

GDF: In “The Daughter’s Almanac” the speaker looks back at “garments of ghost and grave,” then tends to trees and fruits in the present, and says of the future, “I predict that everything is going to change.” What did making this piece reveal to you about the stability of the present and the future of our “unborn cities”?

MO: Thank you for this really thoughtful observation. It puts a finger on my impulse to interrogate that old adage “it is written in the stars.” Whenever I hear that, I often wonder whose stars? Who got to write it and who does it benefit?

At the time of the writing of this poem, news of persistent anti-Asian violence weighed heavily on me. While processing the dangers, despair, and discouragement of it all, the parent in me also felt adamant about not passing on a sense of self confined within the story of victimhood. Whatever dominant narrative may play a role in shaping outcomes, I’m curious about how to reclaim agency in an unpredictable world. Will it be the study of charts, astrological or scientific, the prophecies from our past or patterns of new data that will determine our trajectory? Or, in this constant negotiation with uncertainty, do we decide for ourselves how we want the story to go?

GDF: Yes! Nothing is inevitable or certain, except change. We make the choices we can and learn to roll with the rest, a la Toni Morrison: if you surrender to the air, you can ride it. Is there a poem in Planetaria that surprised you—one that you had to surrender to?

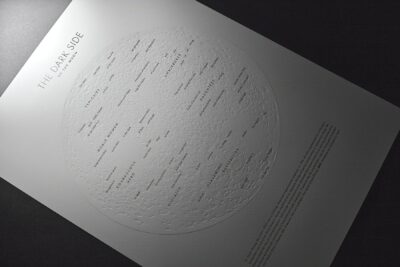

MO: I really loved the experience of making “Dark Side of the Moon” and learning about experimental physicist Chien-Shiung Wu’s legacy, which is finally being fully recognized by her field. I remember one morning at breakfast coming across an article in Scientific American about glasswing butterflies, which are so beautiful but also so transparent that it’s easy to miss them in plain sight. That image completely enraptured me at the most serendipitous moment. To connect her story with imagery of the dark side of the moon was my first time designing with the emboss technique in mind, a challenge that I really enjoyed.

It’s a work that speaks to the perception of women’s labor and the kind of imprint women leave in our professional fields, which is seldom conveyed in the historical record. When in direct light, the moon almost fades to white and you just see the text alone, but when looking at it indirectly or under dim light, the shadows suddenly etch the moon around the poem. There’s contradiction and frustration, but also an awareness that emerges about the collective gaze that has so long been in service of men.

GDF: Planetaria is such a unique physical artifact: four-color printing and a larger page format than a typical book of poetry, even visual poetry. What creative decisions or lessons learned related to its production might help other poets working in visual or hybrid media in imagining their books?

MO: The road from the studio to publication is not a straight line, but a winding journey of iterative learning from many challenges that kept pushing me towards this constant question: when are you going to stop contorting yourself to fit into systems that were never designed for you and start rolling up your sleeves to build the infrastructure that will let you show up whole, not only to your vision but to the communities you are in service to?

Getting published at all is already difficult, but doing so outside of genre convention while also seeking a level of production design closer to that of art books is a really tall order. While rejections and lessons learned were par for the course, it showed me that the pathways we have come to know are just a fraction of what’s possible. Because not all publishing models are alike, working with organizations like the Authors Guild or Volunteer Lawyers for the Arts is essential for authors when evaluating options. In my own journey on this ever-evolving landscape, I noticed an opportunity to contribute a new paradigm specifically in service to visual poetry.

I count myself lucky to be in the company of artists and designers who kept reminding me that when there is no door, you make a door. I paid attention to book artists who blew my mind with radically inventive book forms they were making and disseminating at fairs through their own artist-run presses. I spoke with creative entrepreneurs who pointed me to resources for everything from understanding contracts to managing budgets as a studio business. I studied the work of Fluxus era conceptual artist-writers like Dick Higgins, Ulisses Carrión, and Philip Gallo, who reiterated the reality that experimental artists have always had to create their own presses, spaces, systems, and gatherings to bring their unique visions into the world. I am grateful to the many poets and writers I look up to who vigorously urged me to keep pressing on.

What pathway would my vision have the best chance to not only survive but thrive in? What model would enable meaningful investment in future work? What infrastructure would reply to Walter Benjamin’s insistence on the author as producer, whose central position within the means of production also affords her more agency to take the creative risks the work is asking of her?

The model that had proven efficacy for me was my micro press, Proxima Vera, which I’d founded in 2021 to initially produce my editioned broadsides and gallery-based works. This work that I was once making on the off hours at my dining table was now being embraced as exhibitions at distinguished galleries and museums and acquired by special collections libraries. It became a vehicle that enabled me to renovate space into a proper studio for my work while also building a broad audience.

Working as a visual designer for almost twenty years is where I learned to art direct everything from photo shoots to print and digital publications to marketing campaigns, as well as manage the production of digital systems involving teams of collaborators and vendors. All that training prepared me to meet this moment as a producer. The abundance and artistic freedom I cultivated in the studio also clarified for me that writers, whose labor is criminally undervalued, can empower their practice by insisting on the ownership of the kind of enterprise that supports sustainable and creative independence.

My decision to go all-in with this direction solidified when I won the United States Artists Fellowship in 2024. The award provided additional funding and professional development to bring all that business planning and production management to fruition: I was able to build an artist imprint that could produce the book to the vision of visual poetry that felt truest to me. The joy that comes with that is immeasurable.