Interview // “On What Remains in the Chorus”: A Conversation with Anthony Thomas Lombardi

Saba Keramati (SK): To start with a craft question, do you consider yourself a maximalist?

Anthony Thomas Lombardi (ATL): That’s such a hard question to answer because I feel like I’ve been really reining in my language lately and keeping it simple and I teach to keep it simple, and then my poems end up four pages [long]. I don’t want them to be. I want them to be one-page poems. I’m like, I’m just going to knock it out. And then a lot comes out. I’m talking about a dozen poems that are four pages [each] within a month. So much language comes out of me and a lot of it gets cut. The finished-ish poem, insofar as a poem can be finished, is four pages, after cutting. So I feel like I throw shit at the wall and see what sticks, but I am a very, very obsessive editor and I will spend twelve hours in a row, multiple days in a row, editing one poem. I don’t think you should write everyday, despite what the product-driven neo-capitalist poets say, but editing, I will sit there for ten, twelve hours on one poem.

SK: How many times did you edit the book as a whole? And what was it like originally? Because it’s very long and I don’t say that as a bad thing—it’s amazing and it covers so much depth—but I’m curious about what your process was with a poem versus the entire book as a collection.

ATL: That’s a good question. My publisher, YesYes Books and everybody who works at YesYes, refers to my book as “the brick” because it’s very heavy. It’s 134 pages. My original Gratitude and Notes section was thirty pages and I had to cut that down and it was painful cutting it down. I feel like those pages are more important than the poems in a lot of ways. So thinking of something of that magnitude, that big, you would think that it went through a lot of widescope editing and it didn’t. I won the Poetry Project’s Emerge—Surface—Be Fellowship in 2021 and I was teamed up with Celina Su as my mentor. So, so much credit for where this book ended up goes to her. Just one of the most brilliant minds I’ve ever been lucky enough to encounter. I’m still deconstructing what she taught me. But I had so many poems, so many pages of poems. I didn’t know what to do with them. I was like, I know I want the structure of this book to mimic the twelve steps of AA, but that’s all I knew. I said to her, Here, take these 160 pages of poems and please do something with them and she really, really did. She helped me harness the whole unwieldy thing.

Once it settled and we finished that first draft, we shifted the poems around between steps for a month or two. That first draft of the book almost didn’t change at all. When I edited it with KMA, my publisher and editor, we worked on individual poems rather than the shape of the book itself. I worked on this book for so long throughout my life, living it, it felt like my whole life up to that point was in there, and it just kind of fell into place. It didn’t—it felt like it fell into place—and there was so much work done, but it really felt like I’d just turned around and it was done.

SK: That’s really beautiful. I feel like there is such an emotional development and arc to your collection. I’m not familiar with—if you asked me right now, what are the steps of AA, I wouldn’t be able to tell you off the top of my head—but I felt the emotional resonance as I was reading. I think maybe part of the length of this book speaks to that too—that it’s a never ending process. You don’t stop becoming an addict after you go through all the steps, and I think the “brickness” of this book speaks to that, which is really interesting.

ATL: I’m glad you said that about the steps, because originally I was actually going to have the numbered sections align with the actual steps. It just didn’t make sense, it wasn’t doing anything for the emotional arc, the narrative, the voice or the poems. I was forcing something that wasn’t working just because I felt like I needed to adhere to the steps as if I was in those rooms all the time. Celina and I sort of developed the idea of the steps not in reference to their regimental edicts but the subjective experience of recovery itself, in all its messiness, like you said, that never ends. It may get easier, but it never gets easy. I am never going to wake up and not want to drink myself into a grave. I am never going to not be obsessed with the fact that I should be dead and I’m not.

Here’s the thing: I never finished the steps. My sponsor passed away during step four and I just never had the heart to go back and do them. I’ve just found so much more community elsewhere that I didn’t feel like I needed to. Maybe one day I will, but I feel like writing this book didn’t quite supplant it. Instead, it helped me navigate where I was in my recovery, because I’ve been sober ten years. Now the book’s coming out and covers so much of my early days in recovery where a lot of people that I love died; and people I love have died recently too, they continue to. I’ve always been around people dying. My partner jokes that I was born grieving but it’s only a little bit a joke. When I mention somebody having passed away, recently or not, people are like, Jesus Christ, another one? I don’t think I’ll ever get over it, but I have gotten used to it. There’s no surprise or shock to it anymore. It just seems…like that’s how it’s supposed to be somehow. This book, for me, is like a chorus of my dead, a choir of my dead.

At some point you have to accept it—without acceptance you’ll relive that grief over and over again, which I do but I’m better prepared now. I feel that in a quieter way, your book, Self-Mythology, it’s mythologizing. We all have our self-mythologies, right? Your book feels like there is a choir behind it too, in a really quiet way. While murmurations can be super loud, yours is softer. It’s just a different kind of power.

SK: Yeah, I mean, I was really struck by the way that you invoked your chorus, like all of the references to people, musicians, friends, etc. I found it inspirational and aspirational, the way this book is so willing to go to all the corners—even in the epigraphs. You have Hala Alyan and William Shakespeare sharing the same space, like what is that relation there? I don’t necessarily need to know exactly what it is, but I found that the invoking of all those voices was so powerful and moving and, of course, a testament to the community that helps you through an addiction and helps you live your life the way that’s aligned with your values.

I am really interested—from a craft perspective but also maybe so I can copy you sometime—how do you decide who to put where and what do you, as a poet, get out of naming these people so specifically or providing a soundtrack to a poem and naming not just the song, but the artist and where you are in time when you’re listening to it, etc?

ATL: This is going to sound trite and corny, but I don’t choose. None of us do. I never sit down and think, I’m gonna write about this. I sit down with at best a vague idea and some shit comes out that’s usually nothing like I thought it was going to be. Then I’m like, oh fuck, now I have to work with this. In the larger orbit of the book, yes, these people are in my mind. I’m looking around my apartment right now—there’s Miles Davis, there’s Nina Simone, there’s Whitney Houston, there are poems about each of them in the book. I don’t choose them, but they were already in my orbit.

I didn’t go to school. I didn’t get a degree and I didn’t get an MFA. I didn’t even go to high school. I had to drop out very young for a lot of different reasons but mainly I dropped out to sell drugs, to keep the lights on, to put food on the table. I wasn’t Tony Montana; I just did what I needed to do to survive. My education came from the streets and the radio, because back then we listened to the radio, so I’m like a pop culture pastiche. I taught myself everything from music, film, literature. These things all became my structure, so at some point they’re all gonna jump out of me.

I’ve always been drawn to the idea of what’s antiquated and what’s newly relevant, but it didn’t occur to me until I put them in epigraphs; it first happened in a poem that ended up being cut from the book where I juxtaposed Joseph Campell with Kendrick Lamar and something felt revelatory. We still have so, so much to learn from each other—across age, cultures, race, religion. That sounds banal but I mean it in a much more entrenched way. What we’re saying now is based on what was said by our ancestors, and in fifty years they’ll be talking on what they learned from us. Like the Rimbaud epigraph—Rimbaud was the first poet I ever fell in love with when I was thirteen—so his quote about the end of the world, that’s what it felt like to me back then. I grew up selling drugs in the projects during the crack epidemic. Our heat wasn’t on in the dead of winter half the time, you know. I was dealing to get us by. It felt like the end of the world. The thing is, I had always been doing that coordination between old, new, young, old, all those different things, but it wasn’t until I saw it starkly on the paper that I realized that I was actually looking at the event horizon.

SK: I love the bravery of invoking it all and being so bold in it, naming your lineage on the paper. I think that’s really beautiful. I want to move back to when you said, when you start writing, it just comes out of you and it usually ends up somewhere you weren’t expecting. That’s happened to me too. I’m interested in, then, how you came up with the concept and the process of writing the fragments from Amy Winehouse’s lyrics, but in the book they’re called a stepwork journal.

ATL: Amy’s a tough one. I’ve loved Amy Winehouse since the first time I heard her. Back to Black came out in 2006 and I was listening to it in 2006. I didn’t know I was an addict yet, I was fucking seventeen years old, but I still felt this attraction—not even attraction, but camaraderie—to draw this allure to this person. I always tell people that Amy Winehouse is the love of my life. The people who really know me know I mean it, others think it’s a joke. It doesn’t matter. It’s a love I will never be able to explain to anyone else, but it’s a love that’s more powerful than anything I’ve ever felt for anyone. I’ve told partners that I will never love them as much as I love Amy, sorry, and they’ve all been like, oh yeah, totally, that tracks. But it’s never ever not once manifested sexually, never not once.

SK: Yeah, that wasn’t how you encountered her.

ATL: Right, and when I was even younger than that, I was obsessed with Nirvana and Kurt Cobain, and now that I’m older, I look at this lineage of drug addicts who died before I could love them, who didn’t exist in a time when I could love them, and now they’re in the book. Whitney Houston’s another one, so is [Lisa] “Left Eye” [Lopes]. Lisa didn’t even die from her addiction, which is even sadder that she just fucking drove off a road while trying to help kids get an education. So there’s just been this innate thing with Amy since the beginning, because I lived with her through the cruelty of the media, of people, cruelty I was already accustomed to. I watched her cry for help and I watched the world laugh at her. She was the first person I followed during their career while they were still active, who died.

And then, and this is the God’s honest truth and I don’t even remember my dreams anymore, but during the very beginning of COVID quarantines, I had a dream that I was quarantining with her, and that led to just one poem that I took into a workshop I was taking with Shira Ehrlichman. We kind of butted heads pretty heavily about the poem, about the idea of persona poems and power structures—are you able to write persona poems from the point of view of a woman as a male-idenitifying person, which I’m not even sure I would consider myself anymore. We butted heads and then eventually, typical stubborn-ass me, fought it until I realized she was right. She was like, this poem doesn’t sound like Amy Winehouse. This poem sounds like you. So I edited it into a second person narrative, a narrative that lended her compassion without spectacle, but I didn’t just blanket the whole series as second person, I did whatever I felt the poem called for—how I felt about using the voice, if it was respectful to Amy. The entirety of the stepwork journal series are persona poems and I use her voice quite literally, the found text source being her lyrics.

At that point, the poems weren’t fully formed. I didn’t know they were going to be a series, much less the series of my life. I ended up watching the Amy documentary that I’d put off for so long, because I knew it was going to destroy me and it did; I don’t think I’ve ever cried harder. I cried harder watching that documentary than I did when my mom died. All of these different things just meant that she was always in my heart waiting to come out. I just followed her. Like, oh, another Amy Winehouse poem cool, another one, cool. At some point, I was dating Diannely Antigua at the time, who works extensively with found text and I was inspired by that and also by a workshop with Jay Deshpande that worked with found text, as well. I just decided to do it with Amy Winehouse and what better source to use than her lyrics. So that one was more calibrated, because it needed to be because of its scope. These poems just naturally formed the backbone of the book. I didn’t think there was any other way that I could do it in the end.

I wrote those poems five years ago and recently, over the span of a month, I’ve written 13 new Amy poems and all of them are like three, four pages. I don’t know where they came from—for some reason I needed her to navigate what my life is now, I don’t know. I’m like, well, this is just a thing I’m going to be writing for the rest of my life. Sometimes I won’t write one for five years, maybe I don’t write one for a year, but the new ones are so much more lucid. They’re really in-depth narrative poems. It sounds corny but I didn’t choose Amy. She just kept coming back to me. She always has.

SK: Did you always intend for those poems to become section headers? Or did you expect them to become a backbone in a different way, like center bone, opening bone, last bone?

ATL: I think of it as one long poem. In the book, the reason they’re the only poems on black pages is to indicate that it’s one long poem. But the original poem, the first draft, each step only had two or three lines. It took the “fragments” idea pretty literally. The first line I came up with was, i never loved anyone that didn’t come to me clean as stars & leave a crime. Then little by little I added more and more. It became almost like a puzzle. They came together as a full narrative thing organically over several years.

It just kept growing and growing and growing. I was still writing into it when I was editing the book with my publisher. So I honestly don’t know when that became the thing or whether the idea for that to be the thing led to me fleshing out the poems. One way or another, they just kind of came together. They needed to.

SK: I love that concept, especially thematically, because like you said, this is the thing that’s been sustaining you and something that found you and stayed with you in the same way that addiction would, although one’s less painful and harmful, but I think that’s really, really apt for the experience of reading. These are things that return and come back as you’re moving through the steps. That’s kind of how I interpreted it, but to hear you call them specifically one poem is very telling and I want to go back and reread it with that in mind. I love that.

ATL: The thing is, I am less entrenched in poetry as the foundation of my writing. Music’s always been the propeller for everything, always. So the idea is that the book moves like an album. You could read these as individual poems but, just like with the best albums, you don’t listen to them once—you go back and back and back. I was thinking of certain sprawling double albums for this, like Here, My Dear by Marvin Gaye, which is just like an exorcism, an inferno. You don’t just want to go back, you need to go back. There’s hardly any melodies in half the songs, and even when they’re strung together by rhythm, they’re shambolic, they’re falling apart at the seams. The only way to understand those songs is to go back to them. I just naturally write towards that kind of ordering, of making sense of what’s coming out, a way of engaging with how the work is going to be live inside of something else. If something is a little messy because of it, or a lot messy, or you’re not sure what it is yet…I would just leave it. We don’t need to tie everything up for people. Let’s leave the seams visible.

SK: That’s so interesting to me. My mind works in a completely different way—my mind always wants to tidy something. When I was reading murmurations, I wouldn’t use the word messy to describe it but I would maybe say it’s sprawling and open-ended. But I loved those qualities about it, especially as I was reading, like okay, it’s going to get toward some type of end but it doesn’t. It doesn’t really get a neat ending. And when I say neat-ending, like it’s kind of a bad thing. I think the open endedness is what allows for a lot of the book to succeed. But then I am also interested in the opening and closing “self-portrait as murmuration” poems.

ATL: What you were just saying about neatness is what I teach my students everyday—neat endings don’t exist. They truly only exist in movies. And even then, they are opening up into different conversations. I teach my students that if there’s an answer in one of their poems, they did it wrong—go back and find a question. We should only be chasing more questions. That’s our only goal. The closing poem was actually the first one I wrote for the book before I knew it would even be a book. I remember being at the bar that I worked at, having it on my phone and sending it to Hala [Alyan], who’s been a mentor to me throughout this whole process. Actually, she’s the only one who’s been here throughout the whole thing, from the beginning. I sent that poem to her and she helped me flesh out the Billie Holiday aspects, which originally was only, I think, a line or two and so she helped me kind of get that together. I wrote this whole book, really, at Kan Yama Kan, Hala’s reading series that I’ve been working with her on since 2020. I’m the only one who’s been going there since the very first one, it’s wild to think about—and so I wrote this whole book going to those readings and reading at the open mics with my beloveds like Theo [LeGro] and Lara [Atallah] and Ashna [Ali] and Kamelya [Omayma Youssef]. That was our generation coming up on the open mic scene. It’s beautiful to look back on it and be like, that was us cutting our teeth and writing our books and now we all have books out. It’s beautiful to see that come together, their books are so, so powerful.

The whole thing took about a decade, but the actual physical writing was more like four years and it all took place at Kan Yama Kan. When when my mother died, I went straight from the funeral to Hala’s, when it still took place in her back yard, with all my bags—I recognize the obvious metaphor there—that’s how much that place means to me, how much Hala means to me and how much it’s a home to me. I don’t remember when the idea came for bookends. I love bookends—which seems counterintuitive because I don’t like neatness—but I feel like they open up so many more questions. There’s a lot of trauma in that first poem and KMA was like, we can’t open this book with an eight page poem, we haven’t earned the reader’s trust yet and I was like, no, no, we have to. I wanted that visual effect—how the form mimics a murmuration—when you started the book, as soon as you open the book. I wanted to introduce the reader to this long, sprawling poem rooted in the past and the poem at the end to lead us out on a quieter one in the present, one a little less neat but that still has it together enough. And they just came four years apart. I wrote them four years apart! But KMA helped me with some of the rougher edges, the first one, it didn’t, in the end, need much, but it needed what was done, it gave the reader sturdier ground to stand on.

SK: Well, I think it opens the question of, what’s the beginning and what’s an end? And going back to what you said about an album, the way to experience it, is to listen to it over again. And we don’t, most people don’t really do that anymore, but if you have a record, you just flip it over and start again, right? I think your book does that a little bit, like when it ends, it starts back at the beginning, and it’s replaying itself almost, or it’s asking to be replayed or reread in a new way. I’m curious too about this poem you wrote four years ago—how did it become the title of the book?

ATL: You know how you write a poem a million years ago, and then you kind of forget how it came together? They all, with the passage of time, become mysteries, but I remember that one. I was watching a video of murmurations on YouTube and there is this video, you had to really look to see it, but in the corner, a hawk just fucking snatches a starling—but the murmuration keeps going and keeps going. I was listening to a lot of Billie [Holiday] at the time and so I’m thinking of Billie Holiday and the neglected among us, especially people of color, especially women of color, and especially black women, who are so often left on the curb, kicked aside for illnesses most privileged, white people really, are treated for but women of color are villainized for, attributed with moral failing and that happened to Billie Holiday, along with so many others, and so many people in the book. I mean, that, in essence, became the book. The book became me finding a kind of communion with these musicians beyond the music. Again, I grew up on music, not poetry. I consider myself, foremost, a music lover and writer. That’s what I do. My apartment, my life, everything, it’s all filled with music, records, tour posters, you know. It’s all music. You were talking about the records earlier and I have thousands of records—I’m looking at them. I was just listening to a record before we did this call. So I found communion through that poem, like that poem held it all. It was the whole book, all its universe, in one poem.

It was like a microcosm of what I wanted to do—to open up a conversation about the peripheral, the people who get picked off by predators or nature, you know, storms, natural forces or whatever, and then the musician who is an addict—I don’t think I really talk about any white addicts, I mean, Jaco Pastorius, but that poem is more about his bipolar disorder than his addictions—because I grew up listening to rap, soul, jazz, and the experience of music was so communal in the projects, all of us piled on top of each other trying to find some joy. That stoop culture—sitting on stoops with boomboxes listening to the mixtapes we made off other tapes or the radio. They sounded like shit but that’s what we had. I learned from those cultures and those environments and those communities more than I’ve ever learned from, I don’t know, an Italian community. The way I represented what I was trying to do, the community as a whole, the peripheral, the vulnerable amongst us and how they’re forgotten, I used music and birds to tell that story—just the name, murmurations, sounded so musical.

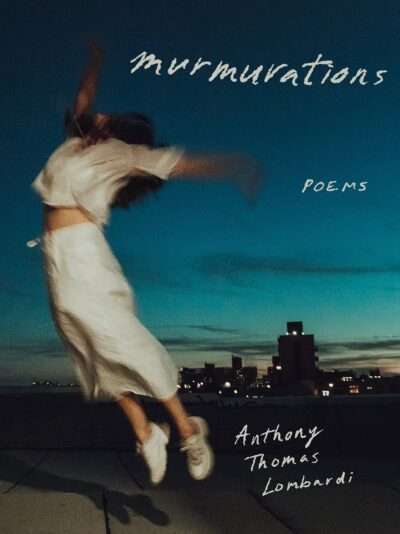

SK: It definitely is and I think, too—maybe this wasn’t your intention—but as a reader, I’m also feeling this sense of a murmuration as so many separate parts that become one, as its own sense of community, as its own sense of a book. You have all these individual poems, but it really, really comes together to tell one story, even as sprawling as it is, and however many references there are throughout the text, it’s all really becoming one. Each poem, each bird, has its own past and everything that it’s bringing in with it, but it’s creating one image. I love what you said about the book as an object. When you were saying you wanted some of the black pages, and to open the book with what looks like a murmuration. So forgive me if this is a sensitive topic—I know for some people it is—but can you talk about how you chose your cover?

ATL: Oh, this is kind of a long story. I originally wanted a Francesca Woodman photo. Typical me, I was like, I’m not doing this book without it. If I can’t have this, I’m not doing the book. Fuck y’all. To be very over the top and melodramatic, I mean, the Italian stereotypes are not totally inaccurate. I remember watching a documentary about Martin Scorsese and how, at some point, there was a voice, it was an audio problem or something where there was a voice in a scene with Joe Pesci at a bar talking to someone, at the Copa, and Marty couldn’t get it out and he was like, take my name off the project, it’s not a Marty Scorsese picture. And it’s like, motherfucker, this is a masterpiece! This is your masterpiece!

SK: Wait, which movie was it?

ATL: Raging Bull!

SKL: Stop!

ATL: I’m deadass! Joey is talking to somebody and there’s a voice Scorsese couldn’t remove, that wasn’t supposed to be there. Very much in the vein of a melodramatic, emotional Sicilian. I was like, if I can’t get this picture—, this picture was part of the book’s creation, its inspiration. I lived with that photo throughout the entire time I wrote the book, it inspired so much of the writing. My publisher said she loved it—she said she rarely if ever loves a poet’s choice for a cover, in the sense that they’re usually too close to it and can’t see how to draw in a reader from the outside of it, but in this case she said, I love this, I think it’s perfect. I’ll reach out to the Francesca Woodman Foundation and they told her they don’t allow photos to be used on the covers of books unless they’re art books. I guess poetry isn’t art? It was written into the texts and contracts for the foundation, you know, by her parents, I think, probably her father. So it’s not like anything could be changed. But my friend, Alex [Dimitrov], the cover of his book, Together and By Ourselves, that’s a Francesca Woodman photo! And so I asked him how he got the rights, and he was like, you know, his publicist or publisher, whoever it was, was friends with Francesca’s father and that’s how he was able to get it, but he’s dead. I was heartbroken. I was like, I don’t know what I’m gonna do.

I looked through so many Instagram artists’ accounts. I went through so many thousands of photos, saved so many. But then this friend of mine, Savannah [Lauren], is a brilliant photographer—all of the photography in the book is hers—but she mostly does events and portraits so I just asked her, getting desperate, not finding anything that worked, that fit my vision, to just send me all the weird shit she had that wasn’t a portrait or event photo. She sent me a fucking bag full of weird shit and me and my publisher went through them and there were a lot of things in there that just grabbed me more than any of the thousands I’d looked through. The one that made the cover, I didn’t even look at it. There were all these photos that were so visceral, from the same photoshoot even—the woman had a bag on her head and she was running around on that same rooftop in Brooklyn, but the lighting was harsher, it had sharper definitions and washed out colors, it was really in-your-face and I wanted it. KMA said it was a little on the nose, and I’m glad she did. I sorted through that particular shoot and was like, what about this one? I was like, holy shit, how did I miss that? And I just fell in love with it. It captures the sense of the verbal “murmur,” the sound of murmurations from a softer and more slanted angle. There’s no birds in it, she’s out of focus, which says murmurations to me. There’s a softness, like something coming together in a quiet way, and I absolutely would never want anything else now.

SK: I love that. I think this cover is so rooted in the city, which I feel like your book also is, and it’s very magical. She’s almost disappearing into the sky and she’s, you know, dressed in white, she looks a little bit angelic. I’m so fascinated because I remember when you couldn’t get that photo, how upset you were, and I was so curious about what you were going to come up with. This is very different from that photo but it’s really beautiful.

ATL: Yeah, the colors are so beautiful and you’re right, the city is so embedded in this book. In less obvious ways, I don’t name New York or Brooklyn very often, but you understand that landscape and how we are navigating it.

SK: Right, absolutely and I think, I mean, obviously New York comes with its own history, but I think it’s less about naming the city and more about the specific experience of growing up as one would, poor and around addicts, within that context and world—that totally, totally comes through.

ATL: I’ve always been struck by cities and places used prominently, almost as their own character. It’s become a bit eyeroll-y for people to talk about now because of misinterpreted brawn, but I was really influenced and moved by how The Wire uses Baltimore in this novelistic sense that doesn’t feel like a TV show or a movie, it feels like literature. It’s Dickensian, the way Baltimore is used as the central character. That is the central character of the show. It’s not McNulty, you know, it’s not Stringer Bell, it’s not Omar. It is Baltimore.

SK: I think your book, even regardless of its length, is a bit novelistic. There are just so many characters, there are so many threads here and there that weave into this tapestry. In the first poem, there’s that line, the last time i told the truth, my mother asked me where it hurts, then that poem ends, i haven’t remembered anything since. There is so much residence in this book—some poems take place in the past, but there’s so much now-ness in this as you’re reading it. It really brings you into the thick of it. It’s almost like the book is a character or the way a soundtrack might be to a movie.

To hear you talk about music, I think that’s what most people’s first experience of poetry is—music. I think the differentiation between them probably has done more harm than good. Ultimately, that beating heart, that rhythm that exists in an album, the way it exists as poetry. I never understand people who listen to something the first time out of order. I don’t get that, same with a poetry book. I don’t get that either. This book is so well put together in the sense that it requires you to read it in order. Ending a poem that says where it hurts, then to have that many pages of all these remembrances and all these occurrences that tie back to it, is so fascinating and just makes for a really powerful reading experience.

ATL: I think nonlinear isn’t the word because you have a narrative without it being linear, right. Even if I make a playlist or mix for somebody or whatever, I tell them they better listen to that shit in order because I spent a long time sequencing it. Do y’all think we just put those poems in a random order? We agonized over that! We probably still do! So again, as somebody who has lived perilously inside everything I work on, I live within an LP setting—a vinyl record’s front and back in order. That’s why I’m drawn, like I said before, to double albums. They capture, in a way, I need two fucking albums to say this. The whole is more than the sum of its parts. The White Album, that album is all over the place. Sign o’ the Times by Prince. That dude’s doing like slow love R&B, robofunk, gospel—he’s doing everything. Even by today’s measures, like Miranda Lambert’s The Weight of These Wings is supposed to be this breakup record, but she’s not talking about the person she broke up with, she’s not tearing down an ex the way she did on Crazy Ex-Girlfriend, she’s talking about her life right now, the good, the bad, the messy, the fun, the heartbreaking. You know, “I left the bar after closing and the bartender hated me,” then later on, you hear her offering the Tin Man her heart. That album is about the messiness of not just a break-up, but grief, how it carries us through loss, how life still goes on and we have good days and we have bad days, you know? It isn’t narrative. And even though she divides the songs between “the nerve” and “the heart,” it does not adhere to that, it careens all over. It refuses any kind of rulebook; it’s guided by emotional whims. That song had to come before another to make emotional sense. Sequencing gives it its weight. So when I see that across a double album, sometimes two hours of music, I get all hype, that shit is so inspiring to me, but also mind-breaking, like how the fuck did you do that? I just try to do the same thing within a poem and then within a collection.

SK: I feel that way reading the book, like how the fuck did you do that? Because that is a lot of pages to sustain that emotional energy, but it’s doing it.

ATL: As far as the energy goes—the bit about my mother is actually, particularly, a key that I didn’t realize was a key at the time because I finished this book a while ago and I finished writing that poem a while ago. In the interim, my mother passed away, which brought a lot of previously buried things to the surface. My mother died from addiction, she died from alcoholism. There’s survivor’s guilt there but there’s also the fact that I wrote this book about all these musicians and people I had communion with who died. I’m like, how didn’t I put two and two together at the time? Now, literally, it’s all that I’ve written about since. I’ve written over 200 pages of another poetry collection, 130,000 words of a memoir, and it’s all about her, it’s all about my mother. So saying that I haven’t remembered anything since now, especially, makes so much more sense to even me because that period of my life, when my mother was my life, laid the foundation for the rest of my life, whether it was my relationships, the decisions that I’ve made, or my emotions and how I navigate them. Everything came from that. She’s only explicitly, really, in a handful of poems—but she is the book.

SK: I mean, she opens it up for us and that’s what poetry is, right? That’s why we end up writing—we’re working through that shit and we don’t necessarily see how it connects. There’s so much that comes after a book is done that you realize you have a lot more shit to write about.

ATL: Yeah, the thing is that no book is done, no poem is done, you’re going to continue to learn from it and everything that you do after is just an extension, right? One thing, then the next.

SK: I, for one, am very excited for the next poetry book and the memoir, whenever they come.

ATL: Yeah, you think this book is heavy?

SK: Oh my God, you’re just going to destroy us all.

ATL: My partner reads everything I write, you know, she’s read a million dead mom poems and I wrote this trilogy of them between the second anniversary of her death and Mother’s Day and when she read them, she was like, with tears in her eyes, your mom poems are always intense but these made me cry. I don’t know what I did differently, but you can’t get here before there. I just keep digging, the poems are just to keep digging, and that’s all. Now I dug through a fucking planet to the other end. Now I have to go and dig my way back.