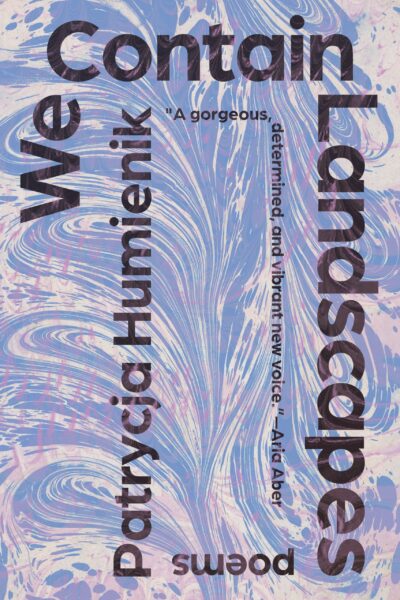

A River Rushing Superimposed Boundaries: on Patrycja Humienik’s We Contain Landscapes

We Contain Landscapes

Patrycja Humienik

Tin House, 2025

Sound by sound, line by line, each particle of We Contain Landscapes routes through the body—its water—before it exits through the mouth in a defamiliarized and transformed language. Aria Aber describes Patrycja Humienik as the next of kin of the great Polish poets of the 20th century. I agree, and whereas many of these ancestor-ghosts show up in the text, the one whose presence I feel most closely is Adam Zagajewski. Humienik’s speakers praise the mutilated world, holding its wonders and imperfections as a part of their own capacious and various interiorities. They commune with land and water, their mutilations, and, in doing so, create salves for their wreckages. No surprise, then, that it is in a poem titled “Borderwound” that invokes Poland’s great poets as subjects of a land that is geographically unstable but geologically stable: “Each time Poland was erased, the Wisła river remained. Can a river unwound?” With this question, both the landscape and its ghosts are revealed to be contained within the body of the speaker.

I feel them moving through me, too, as I read. Like Humienik, I am also the daughter of immigrants—Polish and Afghan. I remember a patriotic song, often taught to children like myself, that follows the flowing Wisła across the Polish countryside. The lyrics of this song describe the river seeing the city of Kraków, irresistible to her despite her journey. The natural landscape falls in love with the urban landscape, and as a token of her admiration, the river offers Kraków her body, metaphorized in the song’s lyrics as a ribbon.

I imagine that a river like the Wisła might share its desire with the speaker of “On Belonging”: “I want body, I want form./ Without the rot of control.” These are lines against dams, drainage, and extraction; they seek to allow what is wild to wind, as it will–in the poem or the flesh? I wonder where rot is permissible, where its origin might not be in control. Rot is a specialty of water, even as it moves and swells at the whim of land and weather. In a previous, contradictory section of the same poem, this speaker does attempt control: “Can’t stop touching my hair. Flatten the curl./ Domesticate and dull. Comb and comb,/ make it straight.” Here is a fragment of the body, resisting the rot of oils transferred from worried fingers, insisting on its uncontrollable form—one that curves into its desired shape. It needs no banks, neither constructed nor organic, to inhabit itself.

Ultimately, repeatedly, Humienik’s poems are liberated by desire—more specifically, by her meticulous attention to the poems’ own desires. I’m thinking once more of the Wisła, of how a river is managed around an urban center, and I question what would become of the body were it to disobey its container. “Failed Essay on Repressed Sexuality” answers me. The speaker of this poem, enraptured by a dancer at a strip club, describes “feeling the ghost of my teenage body./ A river rushing superimposed boundaries.” Another collision—not of poetic giants and legendary landmarks, but of private shadows exposed to the light of lust. “Do to me what sunlight does to a river,” the speaker concludes. A past self teaches the present one to open and gush.

Rivers bewilder anatomy. I borrow here from Fanny Howe’s poetics of bewilderment. Why does a river end at its mouth? More astonishing is the association of a mouth with a cradle. To run down to a mouth, to spring new life directly from a cradle, to pull headwaters from mineral depths unseen… what the body does, land and water copy with their personal logics. The languaging of water’s structure and rituals defamiliarizes us from our own flesh, as it does to the speaker of the second of six “Letter[s] to Another Immigrant Daughter”: “The water I am made of asks me/ to quiet in it.” Though soothing to receive, the ask is constantly disobeyed throughout the collection as the speaker riots against untamable pain (“On Chronic Conditions”), interrogates the embodiment of shame (“Acid Reflux”), and confronts the possibility that she “may never give birth” (“On Belonging”). Still, the water moves, indifferent to the wildness thrashing inside. It confounds me how one can be without and within—the water—the body. Humienik’s poems ignore narrative but accomplish movement, and in that sense, increase my bewilderment.

Like memory, rivers also bewilder time. Water moves but does not run sequentially. Joined in a river-state, disparate drops cannot be counted, nor can any system of accounting make logical the elements of memory that play and breeze in the imagination. Those interior moments, resistant to order—as Howe puts it, “they impact on each other, but lead nowhere.” Humienik’s poem “Wilno” shows us a speaker who contents herself with such aimlessness. In a reverie about her father’s father, she attempts to make sense of what little she knows—“There are stories I long for/ from their source.”—before she surrenders entirely: “Summoned/ like a river by a larger body, I am carried/ in sleep toward inherited longings.”

A landscape painting is a picture of time. Even if the image hides the strata, those layers are always present. They function as the earth’s inheritance bequeathed unto itself, again and again, compacted to depths beyond comprehension. Humienik is not so much interested in finding the origin as she is in exposing the spiraling path in and out of histories that cannot be contained by time. This impulse reminds me of Wisława Szymborska’s poem “The End and the Beginning”:

Those who knew

what was going on here

must make way for

those who know little.

And less than little.

And finally as little as nothing.

In the grass that has overgrown

causes and effects,

someone must be stretched out

blade of grass in his mouth

gazing at the clouds.

I have often imagined myself as Szymborska’s someone, oblivious to the stories I cannot access; now I picture myself as the sleeping subject of “Wilno” as she attempts to recover her ancient longings. For both dreamers, I believe the knowledge or “source” is buried in an interior landscape. But there’s no guarantee here that begets any certain answer: “We contain landscapes./ They do not belong to us”.