A Scale That is Out of Your Control: Notes on Anselm Berrigan’s Don’t Forget to Love Me

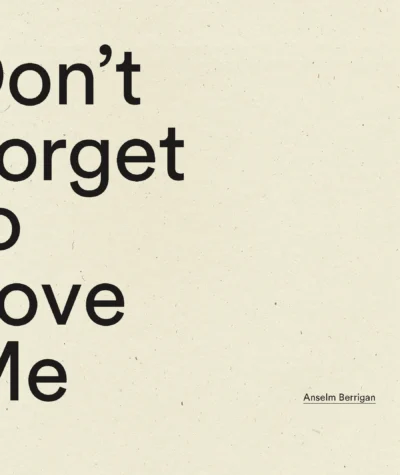

Don’t Forget to Love Me

Anselm Berrigan

Wave Books, 2024

I became aware of Anselm Berrigan while reading Simone White’s essay Flibbertigibbet in a White Room/Competencies. I then began to dig. Son of famous poet parents, Anselm’s ouevre may prove poetry can come in your blood, or, what is more likely, he works hard on developing his voice from and away from his parents and their poetic milieu. In a recent talk at the Hotel Sorrento in Seattle, he mentioned that Allen Ginsberg, upon reading some of his early poems, told him, “no one will understand them.” To get this at a young age and yet to continue writing in a similar vein takes a certain beautiful stubbornness that may be the mark of and a necessity for a dedicated poet.

A life’s work gets real, another exercise in giving chase to a stalwart audience. Anselm Berrigan’s Don’t Forget to Love Me is a big book of poems. Measuring at 8 x 9 ½ and 175 pages this book carries weight in more ways than one.

The title is split unevenly across the spine. Only broken syllables from a straight-on view. Stacked up beside some of his others–Notes on Irrelevance, Pregrets, Free Cell, Something for Everybody–it seems a part of this particular style of title: his main mode is highly notational and his approach to the line is like a hard-edged sketch infused with his self-formulated restrictions. (I’ve heard he is a fan of Philip Guston’s paintings)

The tension is drips

dripping drippingly, the reader wants

a hug

& what will define for me an idyll

The number of words collected overwhelms, first like a wall, then a wave. Wading in, I was carried by the way he breaks his line, keeps me moving down. For moments of extended reading, the poems rise above, raising my body with them. Other times, I wear slippery socks on an oiled floor. There is so much going on, certain things/words reappear, others quickly leave the scene. This is not about being understood–in the world Anselm suggests, bewilderment is a high virtue. Bewilderment, beautiful and confusing, under-/overwhelming, sometimes just right.

This barrier to my left, not the margin, which is also a barrier, may not appreciate my handwriting/ or general presence

Across the four sections–Theories of Influence, Wobble Factory, John Coletti Imitation Racket, Big Sketchbook Semi-Survival Poems, from an ongoing poem for Lewis Warsh, Selected Resurrections, and Notes–Anselm’s role as a sculptor fluctuates, he makes different-shaped poems: classic rectangle, scattershot, the space of the page is contained by the poems, and sometimes the other way around. The poems within these sections are made from varied habits of interest and approach: postmodernism, jazz, language poetry, sound art, concrete writing, the New York and San Francisco schools, and more.

a target as a late mask, an early task

of tearing into finishing, I wish upon you what I wish

upon nobody, a scale that is out of your control.

Notes operates as somewhat of a codex for the larger work; though short, it offers a wider view of the precedings “Theories of Influence is composed of sentences from W.G Sebald’s prose narrative The Rings of Saturn…all the poems in the Big Sketchbook Poems section were written by hand during 2020, and the variations in type size, the deliberate misspellings…are part of what they are on the page…Wobble Factory was written across 2019…” Anselm shares. There is something about getting the poems typed and printed in a way that looks similar to how they are written first hand that is interesting, but is it possible? It ends with a cheeky question, “How does anyone know when to stop writing notes?” I would like to read more of them!

history by implication nuzzles in fragment

as an anti-resonance machine

The poems go this way and that, spitter, splatter, (paint flung on a canvas whose gravity is shifted often) they create a hulking body that then drags bits of its own body behind it. I am lost often, searching for a grasp, for a hold, for solid ground, for even a clue as to how I might read the lines together. Then, there are short phrases that could not be worded any better than how he has placed them. These poems take breath control. As they shift through jokester, musician, jaded sidewalk prophet spitting out what has been collected. Sounds, waves of them, a quantity of slivers cut, in all sizes, from different angles. Neither clarity, maintained evasion of clarity, nor sustained bewilderment are easy. What must the reader know? And how much of it is on purpose?

life on the street

feels more accurate

when we wear

our masks

An excellent dailiness pervades as if a diary has been pushed through a harsh metal screen until all of the data becomes cannonballs, snowballs, spitballs, an empty plastic bag seven stories high on the wind between the buildings downtown. An example of the human ability to process the life in and around us. Consume and produce, conversion and metamorphism, for better or worse an onslaught of things and feelings in word form that fence with reality. He meets/exposes something, then immediately glances off of it, creating a succession of closures. Not in another direction entirely, there is a certain tone. He has his voice and he runs with it, in a multitude of contained explosions, some are more breathtaking than others, but all have their effect on the reading body.

I started writing to be myself, now

I start by imagining someone else

don’t worry about pretending I’m not

trying to be you without finding myself

all over an advance on again’s plateau

the writing is in the arrangement but

it (a pronoun) was never meant to begin

sleep on the couch & the monster tower

walking single file away from destruction

Moments sit as sudden islands of firm brilliance. It was hard to stop reading this poem, titled by asterisks. What does the destruction move into? “Again’s plateau,” is awkward but begins to make its own sense. Here, and on many other pages, I am inspired forward easily. It feels a little bit like tumbling, tripping for an instance before I come to. Anselm seems able to write endlessly, did he get it from his prolific mother, or father, or plainly worked his way to it? How often does he fill a notebook, and how much does he bring out of it? Is it a basic hope/need for everything to make sense? Does life make sense? Yes and no. While many stop at this question Anselm keeps on, putting words to slide towards each other, sharing with us the ones that clatter as well as the ones that blend. Words do unexpected things.