Because Pleasure Counts Bigtime: A Review of Martha Silano’s This One We Call Ours

In loving memory of Martha Silano (September 1961–May 2025)

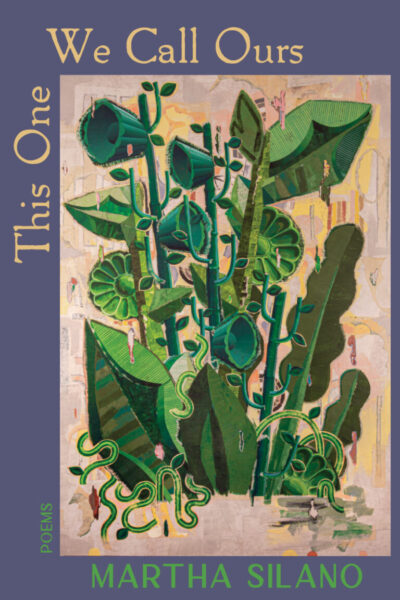

This One We Call Ours

Martha Silano

Lynx House Press

I am already interrupting this book review to tell you it’s the first I’ve written in first-person. I am already interrupting this review because this is a climate emergency and because I’m inspired by these poems’ self-conscious performances of their own creation, as if the author were spinning them for us in real time. I want to talk about spinning spiders and dew on webs. I want to talk about time and distance, vast contrasts in scope, from tubeworms below the bottom of the ocean to the exoplanets, for I have been spending time with This One We Call Ours by Martha Silano. Winner of The Blue Lynx Prize, the book was doubly honored in being selected for the Pacific Northwest Poetry Series by Linda Bierds. To say this book is about the climate crisis is simultaneously true and an oversimplification. It’s about the beginning of the universe, the end of society as we know it, and everything that falls within and beyond that unwieldy frame of reference. This book would like to hold the whole universe in its hands. Its curiosity is relentless, its intelligence boundless. Its shocks of scale enact the vertigo that cognitive dissonance triggers when humanity knows itself to be imperiled and business-as-usual continues to combust apocalyptic loads of carbon.

I began in third-person but the mode was too cold. I could have, with all due sincerity and integrity, praised this worthy book that way, but perhaps not the author. Either way, it’s more than notable the poet has distinguished herself as the author of three poetry collections published by Saturnalia, including one honored with the Saturnalia Books Poetry Prize. You could learn that from the back jacket flap of this lovely volume, but there’s more I wish to tell you about Martha (this is a first-name-basis as well as a first-person book review). Martha is a bedrock of our local literary community. She is well known as a generous teacher, mentor, colleague, and friend in the greater Seattle area. She’s a cherished contributor to this magazine–we published a poem from this book and invited her to read at the online issue launch party. She referred to her recent work at the time as “strident” and that sounded good to me. As a tone, stridency is pitch perfect when this planet, this one we call ours, screams for relief from extraction, pollution, violence, abuse, and the civilization-shattering fuckery best measured by atmospheric physicists. I think Martha may like that I used an F-bomb in her review. She drops them freely when working in the strident mode to defend and protect what she loves, what we all do, this one we call ours.

The gap between what would be fair and what simply is, is, as mortals all know, too often inconceivably astronomical. Or as Martha writes: “What one needs is a helping verb, a word like does. / What one gets instead is a cosmic abyss.” And we are so vulnerable to the vastness of the difference when we pray, in her words, “For just one day, let me grow a carapace.” Consider the chicks Martha recounts jumping from deadly heights in a heat wave so unprecedented it’s called a dome, or the orca swimming in supposedly banned chemicals, her instinct to mother thwarted by that which we call industry. An ALS diagnosis in anyone, especially a beloved community member, defies understanding. You may be familiar with Martha’s diagnosis by way of reading her stunning self-elegies published at Poetry. You may have guessed by now that it’s the diagnosis that moves me to write in the first person. To the fates I want to say, this one we call ours, this author: We wish to keep her. We need her devotional eyes on this mess. We need her wit and will to make sense of the senseless. We need her sense of humor and willingness to swear when sense itself proves impossible. I know she has a close relationship with Apollo, god of prophecy & poetry, for she wields both gifts, braiding them together in this very collection. That’s the legacy I wish here to commend; and I want Martha to know that when she sets her sacred work down, we will pick it up with a bow of deep gratitude.

That might be a good place to end a short review, but this is a long one. As Martha praises the natural world with her powers of attention, I wish to praise her work with mine. The craft in this book is conscious. Every poem feels deliberate, delivered by the poet with the confidence of an experienced singer, even as she overwhelms us with the method of surfeit (what is technically called “letting it rip”). The title, pulled from the line of a poem, milks every word. It centers relationality with its possessive and collective pronouns. It declares: this one, not that one; this intimate, singular, irreplaceable one and only, which we, collectively, call ours in common property and mutual belonging—it to us and us to it. An attentive naturalist observes first the quintessence, in nature, of relationships. The theme of relationship as natural law continues throughout the book. In the anaphoric poem, “My Daughter is Drawn to Blue Flax”, every line expounds upon the premise of the title with a clause beginning “because”. The poem concludes by observing the daughter’s relationship to the object (or living subject) of her admiration: “because every fiber of her weaves in the same breeze.” The poems frequently reveal how our bodies are composed of ancient elements that continually recycle and pass through us while they compose us: “this close to the sea, surrounded / by the birthplace of tears”. In a cosmology of sadness, the very technology of weeping traces back to the oceans. Our waters are not ours alone; they keep moving through and between us, the watersheds, and the biosphere.

Climate grief is a collective trauma that manifests in individuals in many ways, including the anticipatory grief of mourning losses yet to mount upon the losses that have already been. Anticipatory grief can be cold as dread, but it poses an invitation to share honoring that can still be received. Grief after a loss may feel like a frustrated form of love, but before the loss, appreciation can be felt and reciprocated. At any rate, climate trauma is not reserved for the future; it rages in the present and scars the recent past, egregiously compounding existing injustices. At any time, grief may express itself as a spiritual song of praise. Grief declares: this mattered; see how much by its absence—pending or proven. Poems of personal grief such as parental loss are interspersed in this work that primarily mourns the collective loss of the commons. In “Grief is a Planet”, the author artfully collapses personal and collective grief. She mourns her late parents, equating grief with Mars, an inhospitable place: “always looking for life, that’s the constant”. She writes, “Grief is a planet like Mars. The endless search for water. Finding water, / but it’s frozen deep in the Martian ground.” She weaves such potent images with perfect rhetorical control. Over WhatsApp, she recounts a vision to her siblings:

I’ve seen our parents. Not smoke,

not a mirage or bird. They flew to me, black and flapping,

two black swallows

made of something I can’t place. Dissolved

in a white and swirling mist.

Who believes

we could colonize Mars, survive on a planet where storms

kick up dust that sticks to everything,

blocks out light for months.

Who wants to live on a planet where you’d have to wear a grief suit,

where it’s colder than the South Pole, where the water you melt

evaporates like ghosts.

An oracular voice affirms the persistence—even the kinetic freedom—of the deceased, while the living must muck through a light-dimming grief that coats everything like a sticky film of dust. Ever mindful of the future, an eerily knowing and far-sighted voice tacitly affirms the singular perfection of this world by rejecting the absurdity of off-world colonization.

The concept and lived reality of time bind the work together in theme and form. The book is organized by the four seasons with each constituting a section. Specifically, the section titles and contents track the discordance between what our bodies have evolved to expect of seasons and what we now get. They lament their relentlessly unsettling wrongness as ominous portents. In the book, the concerning new contents of the seasons supersede their former names. For instance, the penultimate section, “Freakishly hot, Excessively cold, Anticipation of Heat Dome and Wildfire Season [formerly spring]” is inevitably followed by the final section: “Yearly 1,000-year Floods, 60,000 Wildfires, Fear of Heat Dome, Bacterial Lake Closure Season [formerly summer]”.

For centuries, Western society measured time with two hands. On one hand, the solar yet geocentric Gregorian calendar whose main aims were originally religious in terms of standardizing the calculation of the timing of Easter. On the other hand, an ancient–dare I say pagan–time, which is both astronomical and seasonal: the reliable cycling of the moon and the way the seasons felt to our animal bodies for generations; the way our agrarian societies collaborated with them for sustenance. The poem “No Rain” laments: “The geese honk, fly south, but it’s not fall / without the rain. The lake so low, / exposing a sunken forest. // It’s October, time to plant spinach and kale. / We fill the watering can, dream / of picking chanterelles.” Our modern calendar is a determinative filter of our experience but what fills it changes at an accelerating rate due to the unchecked greed of fossil fuel executives and lobbyists. The book reports on the foreboding discrepancy between the fixed grid of our calendar and what it overlays: atmospheric chaos and its exponential damage to our environment, society, and future.

In addition to cyclical and seasonal time, the book concerns itself with deep time. The consciousness of the speaker moves freely up and down a linear timeline or bounces between quantum timelines. She weaves lyrical cosmologies that sing the stories of how we came to be here, now:

This was how it began,

before it cooled enough for worms and flukes, way cooler

than that instant when everything that would ever be

became, though it would be a while before figs and plumage,

rain drops and touch. But soon we had gnawing,

and soon we had fathers. Falling water

and falling in love. Before long there was work, and there was wine.

Observances like the Feast of Assumption. Soon after

there was rot and grief, But before that: electrons

and quarks. Protons and neutrons. Somehow, we got hummingbirds

and pavement, dorsal fins and cilantro. Somehow, anger

and shame and faith. Now we are a place

for lace and egrets.

Following a list of abstract nouns such as emotional states, I am quite sure “egrets” is meant to be confused with regrets, and damn if we don’t have them now, looking at this mess we made of a miracle. At the speed of light, the speaker bounces from the Big Bang to the dawn of civilization and back again, now forward toward evolution, biological and social. She laces her narrative time travel with wonder and awe.

The poems also look at time in micro, down to that perennial symbol of time, the watch face: “My Watch Face / is a scary clown, a raggedy red-haired poppy. / It’s tell-all o’clock and I’m striking like a grief block, / a whine shield, tuning into a radio station that will teach me / not to scream”. The poet follows the logic of music, employing Plathian wordplay and a half-manic sonic sensibility; perhaps most notably in a poem that calls to Plath’s “You’re”, in which Martha praises the poppy: “you’re an egg yolk, a paper-thin pond / at dawn, anthers waving the anemones / in a rising tide.” When observation achieves devotional degrees, attention is a form of prayer and to sing is to worship.

The corollary to time is space, and these poems also account for distance with literal counting. In an elegiac poem about the Paradise fire titled, “What is beautiful? What is sad? What is apocalyptic?” accounting attempts to make sense of tragedy, succeeding in its factual reportage if knowingly, meaningfully failing existentially: “That in a few hours, the fire had grown to 22,000 acres. That by early evening, / it was 55,000 acres. That in one day it had traveled 17 miles. // Many stopping to jump a beater, give a pregnant woman a lift. / No one knew what effing time it was.” The scale of the tragedy can only begin to be summoned by the wild scales of distance over time that the fire traveled. Time is again summoned in its relation to human meaning-making. No one knew what time it was; it looked like nighttime in the daytime. We can steady ourselves on time, gather our bearings there. When we can’t, it’s truly the heart of chaos or hell on earth.

These are poems that perform their problems and, in the spirit of Rilke: live the questions. In a heat dome poem, “Failed Attempt at Mythmaking”, Martha writes: “I wanted to write about terns” and “I asked a friend how to write a poem / about animals in pain.” The friend suggests a short poem, then an ars poetica, or perhaps to write past the end. Still, in search of her best approach, the author considers mythologizing the tragedy: “I could bring in Hephaestus, god of fire” or “I could bring in Dante’s inferno: Welcome to the city / of woe” or even, “I could mention the patron saint / of animals, I could write past, / so far past—when they’re not, / when we’re not— / but I won’t.” As the speaker performs the problem of writing the poem, we feel the burden of the gift of prophecy: the dark vision and the preference, perhaps, not to know. In the poem, “Planet killer asteroid found hiding in sun’s glare may one day hit Earth” she ponders that perhaps not all knowledge is for the good. She writes, “Maybe we’re not supposed / to see this stuff. Maybe in the dark / is where we belong.”

This kinetic catalog of loss does not fail to uplift a couple of grief’s primary lessons, such as presence and joy. Despite her sense of impending doom, the speaker is aware that everything worth saving is worth savoring: “Because pleasure / counts bigtime. Because days spent in a tender mess / are unrecoverable.” In the same poem, the book concludes with the life-affirming query: “If everything ends, / why are you sharpening your sorrow, / running to catch the discomfort.” Pleasure’s innate importance resists rationalization by its nature—like children, pleasures are immediate creatures. Art partakes in the same self-justifying energy and expands into all the possibilities that creativity opens, including revolution, restoration, and justice. Even if—or especially if—it’s the proverbial end of the world, Martha would have you know: “if ever there was a time / to take up the cello, / this is it.”