Everything Was in The Throat of The World: On Jaia Hamid Bashir’s Desire/Halves

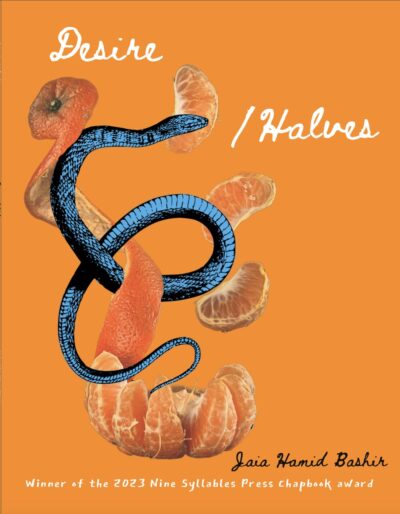

Desire/Halves

Jaia Hamid Bashir

nine syllables press, 2024

In late September 2024, Earth captured a small moon, a “mini-moon” completing a partial orbit around the planet before it departed in late November 2024. There is a Wikipedia article for such “claimed moons of Earth,” with a sizeable subsection for temporary satellites. A small, unremarkable celestial object like that undergoes a mini–moon event when its geocentric energy becomes negative. It would have you believe there is nothing at all astonishing about such an event but for our lingering, enduring fondness for a once-fellow traveler. Even the Moon that is ours to keep was once joined with Earth; it is a tender and becoming confidante for matters of what the self has encompassed and lost. Concluding her poem, “Alone, in Halves,” Jaia Hamid Bashir writes, “Loss is a headless god,” and I imagine someone rummaging for that lost head.

Jaia Hamid Bashir’s Desire/Halves was selected by poet Leila Chatti as the winner of the 2023 Nine Syllables Press chapbook award. Concerning the title of her then-upcoming chapbook, Hamid Bashir wrote, “Well, it starts with Plato,” and delved into the mythological account of love offered by Aristophanes. Aristophanes imagined lovers as beings cut in half. “Sliced in two like a flatfish,” Anne Carson translates in Eros the Bittersweet, “Each of us is perpetually hunting for the matching half of himself.” Further, Carson notes, “All desire is for a part of oneself gone missing.” Catching this forlornness in its many resonances, Desire/Halves transforms from the noun halves of Aristophanes to the diminishing effect love has upon the lover, to the verb of halving. It is a dexterous title, itself halved under the weight and glances of desire. It opens Hamid Bashir’s long, luxurious poems to their task of remembering.

In Desire/Halves, the alluring and unruly ways of memory imbue the speaker with the logic of one who has been torn and cleaved from somewhere wandering a plane of recognition, of Aristophanes’s halved lover recognizing a matching half in vivid images of fruit, the eyes of impossible animals, and the arrivals of moons. Desire is a self made vast, a “godstorm” as Hamid Bashir writes in “Madonna Arms.”

What I want most

is to have multiple limbs. A litany

of different hearts. How much

can I hold?

Such moments of enlarged and confessed want slip through the text and sediment into a legend, a key with which to read the breadth of Hamid Bashir’s poems. Hamid Bashir’s juxtapositions have earned particular attention from her readers, with Shane McCrae writing, “Her vision is both panoramic and intimately close.” A poem like “Pegasus Tattoo on the Left” is made of such varied threads—dream and myth, spacecraft, language and false cognates, the animal and the body—that Hamid Bashir’s juxtapositions are no longer glints of one cracked pane but a surface of shimmer. “A winged horse is a regatta of stars—” she writes, and it is. It has become so now and has borne us here, our gasps and nodding at the opening lines having conjured this one, deepening the incantatory logic.

A horse is a muscular hyphen—

connecting humans to nighttides of the open

animal world beyond us.

Often in Desire/Halves, language is derived from the ways of the animal, reminiscent of letters in an alphabet wrought from Taurian head and horn. In “Divinities,” a poem that invokes several letters in the Nastaliq script, Hamid Bashir likens the cē to “gelled eggs cradled” in a lone seahorse. Hamid Bashir, writing primarily in English, weaves in Urdu and Español in this chapbook—never once offering direct translations, yet, giving pause and, for solely Anglophone readers, a script to read the silence. She invites us to the letter alif not as a semantic or phonological unit but as blades of grass. Elsewhere, of hunger, Hamid Bashir writes, “I’ve eaten the center of a Rodin” and I locate the principal nerve of this set of poems in an invitation toward the unknown and the incomplete. Hamid Bashir does not chart for us what lies there but flings toward us the celebration that it is anything but empty. She invents anew what we call unfamiliar.

In “And the Word for Moonlight is My Name,” there is a simple and stunning image, of a bird ring “patient and sliding on the tattoo of a birdcage.” Planes of meaning seem to meet in this image, like tectonic plates sliding over each other at the edges. Hamid Bashir achieves this sense of peaking, of summits within her long poems, with a rush of enthusiasm that doesn’t look back.

Ma used to preserve each of her calling cards in a glass

vase as if they could blossom as if they were the umbilical

rope tethering cosmonauts to the space station.

Her shift in focus is telescopic. A glance at her mother torn to meet cosmonauts in umbilical tether to their space stations is a nearly Bachelardian move, intuitive and marked with deep phenomenology. It is an exercise in the persistence of vision, image lingering for longer than word, like a temporary satellite, of whom she writes, “Then you will go / back into the dark ravine of an infinity / that goes on without our favors, without our desires.”

Hamid Bashir accomplishes such marvels in her use of language that each blade conjured to invoke loss only whets my desires and asks of language. The first poem from the chapbook that I read, which is indeed the opening poem but I did not know that then, “Stringing the Bow” was published in September 2024, in Virginia Quarterly Review. It reads as prayer or an ode or an incantation toward time that is “cyclic and malleable.” In it, Hamid Bashir writes, “In a parallel universe, Celan / shoes filled with water, is drawn onto the bridge, his heart / resuscitated.” It is a heartrending image, but more so the second time and even more the third. Hamid Bashir leaves me with a litany of all the possibilities her language has opened, and an irrational flicker of hope that perhaps this too is possible. Or this loss is given strength to bloom into something else.