Interview// “A Wild Palimpsest of Histories”: A Conversation with Aaron Coleman

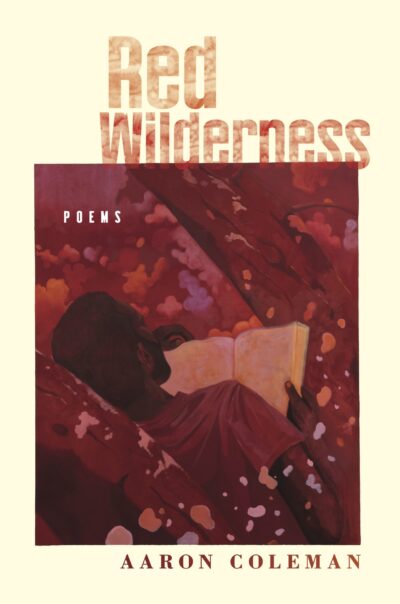

In Aaron Coleman’s Red Wilderness (Four Way Books, 2025), Coleman visualizes an intimate, living archive that maps myths and realities of blood, boundaries, geography, and genealogy, which haunts our country and ourselves. Coleman’s second collection interpolates American history with his own family’s legacy, reflecting on national identity, Blackness, taboo, faith, and remembrance, that stretches back to the Civil War. In these restorative lyrics, an end is an entry point to memory and reimagination, to something unending: a spiritual freedom, collective strength, and boundless love threading separate years into one strand. Red Wilderness brilliantly curates and interrupts the sounds and history present not only in our veins, but in the veins of these United States. What a gift to be interrupted. This interview was held over email.

*

Brandon Blue (BB): First of all, I want to start by saying how much I enjoyed this collection. Red Wilderness considers many different terrains: physical landscapes and places, digital spaces, the internal landscape of the speaker, and, even, the physical body itself. Early in the second section there’s a poem called “Outside Homer, Louisiana” that tackles many of these wildernesses—from forest to region to work to myth to language and much in between. I’m curious to know how you think about place, space, and the black body in those contexts?

Aaron Coleman (AC): Firstly, thanks so much for your thoughtfulness and care in spending time with Red Wilderness. I’m so glad to think about the work with you.

I see the book as an exploration of the relationship between our bodies and the locations we live in and come from. And of course every place we could ever step is a wild palimpsest of histories—there’s loss and violence, there’s growth and love, there’s migration, there are sedimented layers of history in any place we find ourselves.

Let me dive into a recent example that’s worth unpacking here: traveling to the Furious Flower IV Poetry Conference in Virginia last fall, rain pouring on our shuttle bus from the airport (and Nikky Finney sitting just a row in front of me!), I pulled up my phone’s GPS because I was curious about how close we might be to a town mentioned in the enlistment records of my ancestor who served in the U.S. 25th Colored Regiment during the U.S. Civil War. Via GPS I could see that our highway path from the airport to Harrisonburg was only miles away from that town, Berryville, VA, and the South Mountain range in the Appalachian foothills that straddle Pennsylvania, Maryland, West Virginia, and Virginia.

My research on the importance of mountainous wildernesses for runaway enslaved peoples and maroon communities (not just in the U.S., but throughout the Americas) has often led me to wonder about this mountain range as the path my ancestor may have taken to get from Virginia to the small town in Pennsylvania where my cousins first found our ancestor’s tombstone, engraved with the information that he had served in the 25th U.S. Colored Infantry.

We can never know for sure how he found his way to freedom, but I share all of that to say that I suddenly realized on that bus that I was traveling through a strange kind of ancestral ground. I was looking at mountain ranges that at least one of my ancestors, five generations ago, may have looked at in the midst of terrifying risk, terrible struggle. Especially for black folx, the archives tend to fall to pieces at much more recent dates than these, but still this blurry fragment of the history was echoing all around and through me. I could feel something there—I wanted to reach and feel something there. And being there while heading to a multigenerational poetry conference celebrating black writers made it all the more uncanny and powerful. I hope this example makes clear how the past is all around us, in ways we know and don’t know. And this is just one branch via one ancestor, to say nothing of all the other branches that find their nexus in any person.

So it was the deep history of that ancestor that inspired many of the questions that sparked Red Wilderness.

I’m always looking both inward and outward from my body, my positionality, to try to sense the profound alchemy that led to the present moment and what that might mean for our futures. Let me cite some of Alexis Pauline Gumbs’ intuition in Undrowned: Black Feminist from Marine Mammals: “Maybe it has to do with the humility of knowing that while we navigate the predictable there are phenomena old and ongoing that we’ve never even heard about, waiting for us to remember.”

BB: The collection moves almost chronologically from 1864 through our contemporary time with many specific references to people in your lineage. Beyond providing historical context that grounds the collection’s themes, I feel like there’s something more happening with this detailing. Maybe an anthology or catalog of family history? I’m wondering how you see the many functions of a collection of poetry? How it lives past an argument?

AC: I wanted to find a way to affectively convey how, for me, the past feels woven through the present, how the past and present might always be co-creating futures. The opening lines of Terrance Hayes’ poem, “Lighthead’s Guide to the Galaxy” have been rattling around my head for quite some time now: “Ladies and gentlemen, ghosts and children of the state, / I am here because I could never get the hang of Time.” When I felt these family histories and historical fragments coalescing into a poetry collection, at first I thought I’d try to make it strictly chronological, from the archival records we found related to my Great (3x) Grandfather in the U.S. Civil War to present day, but the more I thought about the impact of these stories and how both personal and national histories roam inside of us—sometimes consciously, sometimes unconsciously—I realized that I didn’t want the collection to oversimplify the passage of time. I wanted to find a way to move in waves with it, to dance and push back against it the way memory so often does as we move through our everyday lives. So it became important to weave these familial and national histories into the question of: how do these remembrances, with all the strangeness of memory, live in and even animate my own life?

I’m reminded of something that the late poet Ellen Bryant Voigt often said: poetry is not the transcription but the transformation of experience. That’s been so useful for me as I’ve thought about how these poems speak to life and echo family histories and myths in a new time. I wonder what our bodies do with time, and I see this collection as a living archive exploring that question, both asking and responding to it.

There are more ways that a poetry collection can function than I can hope to describe here, but I will say that I’m most interested in the collections that help me rethink the possibilities of the book form. Similar to the way a music album takes us on its own particular journey—even if our sense of that journey is simultaneously shaped by when and where we happen to be in our own lives as we listen to it (in order or out of order). There’s a dynamic relationship between a book or album and a reader and I hope this collection helps us sense our way into that dynamism and all the voices and histories composed with/in it.

BB: Changing directions, in an interview on NPR, you say that about translation, “even knowing [translation] can’t quite be what it is in the original language, hopefully it can be a creative, productive failure. Maybe it can be something that opens up a new way for us to see what can happen in English and what can happen in Spanish, for me.” While there is a poem in Spanish in this collection, I’m actually thinking about this idea as it relates to some of the more visual, concrete poems and where experimentation shows up in the manuscript. “Do you accept Negroes?” and “” are two moments where breaking the language helps uncover something about its subject in a more precise way. How do you think about shape and experiment when composing a poem?

AC: I love to dwell in the multiple facets or symbols—or let’s say the multidimensionality—of a given word or term. I really think that in many ways language is a living thing transformed by the ways we use it. The music of rhyme sometimes leads me to the underside(s) of a word or term, whether that’s in Spanish, English, French, or the many modes of diction or slang in all those languages. In the case of “Do you accept Negroes?” a family member brought up that back in the 60s another family member had written a letter to a tacitly segregated white church in Michigan that included that question. We all really were feeling the hurt and pain and latent indictment and strength, even, in that question. The only way that I could figure out how to approach the madness of that question—the situation of feeling that one has to ask that question—was to flip its sounds inside out over and over again, to let it echo in all those other possibilities by listening to the sounds in it. There’s obsession and pain there. Forcing it into the form of a kind of dubious sonnet felt useful, too. Maybe I started off ashamed of that question, but the more I’ve thought about it, it’s just a powerful enigma, a daunting conundrum. It’s an inheritance that belonged in the wilderness of this book. I hope it honors the impetus behind my ancestor’s question.

BB: You recently published a translation of Nicolás Guillén’s El gran zoo, The Great Zoo (University of Chicago Press, 2024) which is described by the publisher as a humorous and biting collection of poems that presents colonial racialization, oppression, and exoticism as a fantastical bestiary of ideas, social concerns, landscapes, and phenomena. Translation is often called the closest form of reading, and I’m often reminded of Solmaz Sharif’s “Into English”:

It is very

private

to be in another’s

syntax.

In that close proximity to Nicolás Guillén’s El gran zoo, I’m curious if Nicolás Guillén’s El gran zoo logic shows up in this collection? Are there any poetic tools, images, or syntax now a part of your poetic tool box?

AC: I’m so glad you mentioned Nicolás Guillén and my translation work! And I really feel those lines from Sharif’s poem. I definitely learned so much in the process of translating The Great Zoo. Actually, I’m still learning from Guillén’s dark humor, how the tone of so many of those poems teeters on a knife’s edge between playfulness and deadly seriousness. Somewhere else I’ve said I feel like his poems are winking, smiling, sneering at the same time. But it’s also the way he crafts images that are so concise and potent. I talk more about that in a special folio for Poetry magazine and in an essay titled “Multiplicities of Blackness: Translating the Radical Authority of Nicolás Guillén” in Michigan Quarterly Review. At this point, poems like “GUITAR” and “THE NORTH STAR” will now always be floating around inside of me. I can’t look away from Guillén’s haunting imagistic descriptions in poems like “KKK” and “GORILLA.”

The puzzle of translation feels like a kind of cross-training for my own writing. I love how translation teaches me to listen differently. I love the way you can really walk around with a poem or even a single phrase or line and just try a whole range of different ways to convey its sense(s) in another language. Translating this book and having spirited conversations with Mary Jo Bang as she translated Dante’s Purgatorio and Paradiso was such a gift, really a buoy, during my PhD years. Now I teach a translation workshop at the University of Michigan and I’m always talking about how translation is this tangled skein of loss and gain—even if we lose some ineffable part of the source text’s meaning, new meanings proliferate in the translation.

There’s a bond across languages, locations, and time periods that ties together a source text and its translations. They work together to amplify the text in the language of the original and in all the languages of its translations (Walter Benjamin gets at this in his famous essay known in English as “The Task of the Translator”). I’m so grateful to be in this translational relationship with Guillén’s voice and I’m always thinking about the role of translation in highlighting both similarity and difference between writers of the African diaspora.

BB: Towards the end of the collection in “The Flag Eater” you write so succinctly, “I took what was not food / and made it feed me. I did not choke,” and this feels like an echo of and response to the very first poem of the collection, “i. Figures One Through Two,” an erasure of Samuel Penniman Bates’ chapter on the 25th United States Colored Regiment: “the flag was colored. It represented bondage fallen in the eager form of Liberty.” As we exit the collection, having named, reframed, and traced so much history and so many systems, I’m wondering about your thoughts around these same systems at work now and even in the future? I’m thinking about the power of naming as a useful tool for oppressed people as history continues to be framed for a future audience. As you say in the final poem of the collection, “what is true but nameless / knows no beginning or end,” so I’m curious what can be named?

AC: I just have to mention here how amazing and edifying it is to see how the poems resonated and constellated for you. Both of those moments in the collection are especially important to me (and that moment emerging out of the erasure was mind-boggling!). Thank you for spending quality time with the work.

Let me approach your question from a slightly different angle: One way I read Red Wilderness is as a metaphor for blood, how we can and can’t know what it holds, what it hides, what might root and branch from that wilderness. I also hold the title closely alongside histories of maroon communities in wildernesses throughout the African diaspora. The wilderness, as full of danger and risk as it is, is nonetheless full of possibility and many black folx across the hemisphere have forged refuge in wilderness. So I hope the book is asking what kind of liberation or complex refuge might I be able to forge by escaping into the myths, histories, and realities of bloodlines, of my blood? And what kind of possibility exists in the humility of knowing that I can’t fully know or name my whole story(Whitman was onto something important when he said we can contain multitudes)? Maybe all I can do is keep listening and keep going.

Your question also makes me think of Aracelis Girmay’s brilliant book and poem(s), The Black Maria. Lines that have been on my mind a long time:

Naming, however kind, is always an act of estrangement. (To put

into language that which can’t be

put.) & someone who does not love you cannot name you right, &

even ‘moon’ can’t carry the moon.

It feels important to keep that close, to keep that open. I hope that on some level Red Wilderness refuses the idea of all-encompassing names or categories, or we could say that the book is enacting multiple lenses or re-framings that are sometimes in tension and sometimes overlaid to create a kind of x-ray vision (of infrared!?) through time as I work through taboo, doubt, fear, violence, survival, love, faith, hope. Maybe there’s a corkscrewy continuum/mobius strip between all those things. I don’t know. But I know there’s so much that I love that escapes language, so much that I love that can’t quite be named and perhaps can only be felt.

And that actually might be a good thing. It’s good that some things can’t be completely identified or apprehended. Maybe in that way some things escape being turned into commodities, co-opted by capitalism or some kind of ego-driven dominion or performance. So I also hope the book makes space for a wilderness that holds the possibility of many names and new ways of being together—very old and very new ways of being more of ourselves.