Interview // Bob Hicok

By Diana Khoi Nguyen | Contributing Writer

Bob Hicok was born in 1960 in Michigan and worked for many years in the automotive die industry. A published poet long before he earned his MFA, Hicok is the author of several collections of poems, including The Legend of Light, winner of the Felix Pollak Prize in Poetry in 1995 and named a 1997 ALA Booklist Notable Book of the Year; Plus Shipping (1998); Animal Soul (2001), a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award; Insomnia Diary (2004); This Clumsy Living (2007), which received the Rebekah Johnson Bobbitt National Prize for Poetry from the Library of Congress; Words for Empty, Words for Full (2010); and Elegy Owed (2013), a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award. His work has been selected numerous times for the Best American Poetry series. Hicok has won Pushcart Prizes and fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation and the National Endowment for the Arts, and has taught creative writing at Western Michigan University and Virginia Tech.

Read Hicok’s “Isn’t physics fun?” on the Poetry Northwest website and find more of his work in the Summer & Fall 2014 print issue and online here.

When did you first start writing poems?

I was 20. My girlfriend broke up with me. (A moment of sadness, please.) I stopped at a drug store and bought a pad. Though what I scribbled was more of a song than a poem. More of a thrash than a song.

I love that—the poetry at its beginning is a thrash. Speaking of beginnings, who were your earliest writing crushes?

Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young. David Bowie. Bernie Taupin, who wrote Elton John’s early songs. He might be the first person I thought of as a writer. Van Morrison. Rickie Lee Jones. Elvis Costello. I find it awkward when asked about influences—there’s no poem in me the way a song like “We Belong Together” is in me (Rickie Lee Jones. Pirates. Give it a try.) I was around some people this past weekend who said they never pay attention to lyrics and I couldn’t understand that. My interest in language—in public language—was born on the radio.

Those are some amazing writers/artists. I once taught a beginning poetry class to non-English/Literature-majors who hadn’t read much outside of what was assigned K-12. On the first day, I asked them to bring in something that represented writing/“poetry” they admired—and because many hadn’t read much/any poetry—many brought in incredible song lyrics.

I know that before you started teaching, you ran a successful die design business—how does one get into the die design business?

By quitting the lawn-mowing business. My boss wouldn’t give me a raise. And he got pissy when I cut the sleeves off my t-shirts. There was a lawn-mowing dress code, in his mind. (Though it would look swell to see someone wearing a black tux against all that green.) So I quit and my dad got me a job as a runner with a die design company. (A die is a large object that stamps out metal parts, for all of you not from Michigan.) A runner made blueprints of the designs. I thought I’d do this for a summer but it turned out I had a knack for seeing things in three dimensions, which is the main requirement of the work—to see what isn’t there as if it were. It’s a business that’s largely disappeared, like a lot of work related to the automotive industry. Disappeared or left the country.

I think this “knack” is immeasurably important to poetry—to art: “to see what isn’t there as if it were.”

What compelled you to pursue a low-res MFA after already having published four books of poems? Do you regret this decision?

After a year as visiting prof at Western, I decided I wanted to teach. But I had no degree—undergraduate or graduate. I was told that I’d need an MFA to land a job, so I spoke to the folks at Vermont College, who gave me a good deal. I think I was a semester in when I got the job at Virginia Tech.

Regret? Not so much. It was kind of a non-event, really. Though it was great to see some of the teachers at Vermont in action. David Wojahn especially. He’s very good at responding to poems—at seeing the poem for what it is or wants to be. But I didn’t like workshops. I’d gone too long making up my own mind about my work. I was a hermit dropped into a dinner party. Pass the leaving, please.

And how did you get the visiting professor position at Western?

I answered the phone. The poet William Olsen called and asked. That’s probably my least complicated academic moment. I’ll always feel grateful to Bill and Alexander Graham Bell.

So you’ve also been a waiter, dish washer, lawn mower, factory worker, door-to-door salesman—any memorable stories you’d be willing to share with us from these jobs or others I failed to mention?

Two come to mind.

I’m delivering pizzas in a suburb of Detroit. I take a pizza to a hotel down the road. Guy answers the door in his underwear. There’s a woman on the bed in a negligee. He waves me into the room, pays for the pizza and gives me a hundred buck tip. Says, this is for you, and then nods his head in the direction of the woman, who’s smiling at me the whole time. I ask him twice, are you sure you want to give this to me? Both times he says yes. Then I leave, making this story far more boring than it was supposed to be.

I’m working in a stamping plant. We’re all dressed in khaki jump suits. My job is to pick up a Mustang door from a conveyor belt, put it in a trim die, press the two paddles that make the stamping press go, over and over, for eight or ten hours. One day a guy walking by lights his jumpsuit on fire—I don’t know what was on it, but something flammable. Just reaches down with his light and poof, his thigh is in flames. And without missing a beat, a guy going the other way throws pop on the fire. The two never talk. No one else notices. And life seems about two sizes too big.

These are incredible stories—I’d read a book of Hicok’s Parables for sure. I’ll remember these stories for years to come.

As a young person working on her first book, what I always have to ask is: How did you get your first book published?

Contest. The Pollak. I have no secret to convey. I put my manuscript in an envelope and put the envelope in the mail. So stamps, I think, were the secret of my success.

If you could talk to a younger Bob, say, Bob in his mid-20s, what would you tell him?

Not to listen to older Bob.

Do you have any advice to young writers who are struggling now?

Enjoy struggling. There’s a purity to writing (to anything) when it’s done for its own sake. When no other eyes fall upon your shadow. I wish poets could hang on to that longer. We want so much to come from our writing (really, I think, a lot of us want to be famous, which is a categorical mistake), but for the public things to happen, the private moments need to remain genuine, pure. The ones who succeed write the way they want to, not as they think they should. Which means there’s a lot of to hell with you to doing this. The more you have an eye on the world and who’s knocking on your door, the harder it is to be your own person. So hole up. Cultivate the chip on your shoulder. Let it grow into a tree.

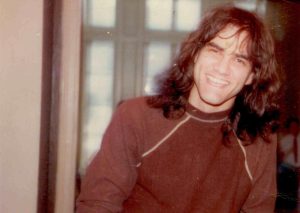

Do you have any young BH photos you wouldn’t mind sharing with us?

Sure. I’ve included a before and after set.

A native of California, Diana Khoi Nguyen will be the Roth Resident at Bucknell University in the spring, where she’ll continue work on her first manuscript. Her poems and reviews appear or are forthcoming in Poetry, Gulf Coast, Kenyon Review Online, West Branch, Lana Turner, and elsewhere. Diana spent the autumn at a residency in Blönduós, Iceland sculpting wool and weaving. www.dianakhoinguyen.