Interview// “Observation as Practice, Comparison as Dispatch”: A Conversation with Brandon Kilbourne

Brandon Kilbourne writes, about his debut collection, Natural History (Graywolf Press, 2025), that “the work of writing about hidden histories is at heart an act of seeing.” Natural History weaves entanglements of slavery, naturalism and bioprospecting, by taking a look—at an evolutionary biologist’s pace—back and ahead at the earth and its species. By taking his readers into the Age of Discovery and its “hidden histories,” tucked into dioramic scenes, a biologist’s fieldwork, and one’s sense of place and self, Natural History insists on a closer look at biological and creative inquiry and its cross-scale consequences. I was grateful to meet Kilbourne this past summer, ahead of the release of both of our debut books of poetry. Through questions and follow-up exchanged via email and Google Doc, after our time spent writing for a week, Kilbourne agreed to share these insightful responses on the inter-relatability and flux of time, and our time as species on earth.

*

MaKshya Tolbert (MT): I want to start far into the collection, or far back, with “Dispatches from Ellesmere Island,” the third section of Natural History, composed of a series of poems sequencing through roughly a month of field work on Ellesmere Island. Much of this section focuses on time spent recovering new specimens from the Devonian Era (roughly 360 million years ago). What bewilders me bewilders the person(s) moving through these poems, who are described as “caving to curiosity.”

Your dispatches throw readers into what it is to both be awed in place and where one is, and to also time travel 360 million years back to the “Age of Fishes.” Study and field observation are portals into what once was, and was changing. (According to my very elementary search, our first forests, first seeds and soils, and first plants reproducing on dry land. Not to mention insects, spiders, and early tetrapods. Wow!!)

These fossils offer a place to set one’s attention, but also blur my sense of time. (Is that due to my newness, or to some quality or character of fossils themselves?) You write: “eyes glinting with our present story, / before it too is compiled with the past.” Both across the collection’s sections, and also within the sections, the present, past, and future seem linked, but how? Are you blurring our senses of time, or sharpening them? How were you thinking about movement, inquiry, and time in this section?

Brandon Kilbourne (BK): Well, I would say that a paleontologist’s eye is central to many of the poems found in Natural History. To study ancient species is to reflect upon the history of the planet and the countless lifeforms that have populated it from today going back to the origin of life itself. When thinking of evolving species, when thinking of shifting continents, when thinking of changing climates—even thinking of cataclysms, like the meteorite impact that wiped out (non-bird) dinosaurs—these changes and events comprising the Earth’s history have produced the planet’s present moment. Essential to the study of evolution, in particular, is that today’s diversity of species can be traced back through earlier and earlier waves of ancestral species, with each wave of ancestral species having fewer and fewer species the further back in time you go until the lineage ends in a single species, a single ancestor that underpins today’s diversity. You can think of it as being a little similar to retracing the living members of a family back through earlier and earlier generations to a particular ancestor. So there’s an inherent perspective in studying paleontology and evolution that the present is owed to the past. But this perspective I don’t think is unique to the paleontologist or the evolutionary biologist. I’d wager historians of all stripes, from world historians to family historians, likely have a similar perspective. So that’s the past and present. Where the future comes in is the realization that the processes that have acted in the past in terms of evolution, continental drift, and climatic changes will continue to act in the future. So, the study of the past yields insight into what the future could bring. This means that there is not a blurring of the past, present, and future, but more a realization how they are all interrelated.

As to your question about movement, I would say it’s not so much movement exactly, but an awareness that things—especially over geologic timescales—do not remain static. Flora and fauna, landforms, environments all inevitably change, and my poetry tries to convey this.

MT: Natural History insists on following wonder and its shadows, marked out as much across one’s inner life as across the Earth itself. You write in this same section: “But since when has the compulsion to consume / ever abided wonder?”. What’s the relationship between curiosity and the compulsion to consume, in Natural History? Curiosity has its edges…you write in the book’s middle, in the poem “It Came from Beneath the Sea”: “Grateful for the goodwill toward my curiosity.” And there’s a relief I read there—perhaps for one’s own motivational world—relative to those of the ‘explorers’ and naturalists who took part in the “so-called triangular trade,” as you note in the book. Where does curiosity end, and the “compulsion to consume” begin, across your collection? Where does seeing go well, and where wrong, or too far?

BK: I am not sure if there is a clear edge to where one transitions from one into the other. Among the early European naturalists setting sail in the Age of Discovery to explore the world outside of Europe, the impulse to find “undiscovered” plants and animals was really fueled by opportunities for bioprospecting, regardless of whatever genuine curiosity those naturalists had. The financial backers and funders of those expeditions, whether it be a monarchy or a merchant, had hopes of getting a return on their investment in terms of natural commodities they could sell as medicine, dyes, wood, spices, etc. And a big part of this was competition for “new” natural resources among the empires as they vied for dominance. Though odd finds, whether it was a manmade object or a strange object, could be added to a cabinet of curiosity, which I would say were the purview of the wealthy. Cabinets of curiosity eventually became the basis for many museums, and early on, museums, at least the larger ones, were expressions of imperial reach and influence, showcasing colonial possessions in terms of plants, animals, minerals, or humans, with regards to both the physical bodies of and the objects made by those humans. I would say that these early museums grew out of a desire to show a curious public the world, but that went hand-in-hand with the message of the empire’s ability to bring all these objects and people from the ends of the Earth under one roof. In many ways, it was also showing the public a world away from “civilization.” I would say that as societies became more multiculturally sensitized and globalized (and as empires fell apart with colonies gaining their independence), there was a shift away from the messaging of empire to messaging about the wonders of the natural world and the value of science. So that’s all to say that curiosity—at least at the level of building a natural history collection—and empire have been deeply intertwined historically, even if it might seem like an odd connection today. And it has to be remembered that perhaps the chief incentive of empires to explore the natural world was to find new resources to exploit.

In this larger context of curiosity alongside consumption, goodwill is not associated with relief, I’d say. It’s more the possibility of having an interpersonal exchange, or a brief connection, not weighed down by the past. Earlier, in the poem, I write:

amused that my discovery of a shellfish

would leave me so visibly transfixed,

especially since in all likelihood

this is a creature that he commonly sells

which tries to acknowledge the contention of discovery; is something truly a discovery if it’s already known to circles, communities, or cultures outside of the ostensible discoverer’s? Moreover, while discovery has a positive side in terms of advances in science and the creation of knowledge—please don’t misunderstand me on that—it also has had a negative side in lands that would later be colonized. Often the first encounter (i.e., the supposed “discovery”) between indigenous peoples (as well as animals, plants, and minerals) and outsiders was a tragic milestone that ushered in a history beset with horrors, oppression, and exploitation. So, the speaker in the poem is left feeling some level of gratitude, in light of this history, that an outsider’s sense of discovery, even on a personal level, can be met with generosity and goodwill.

MT: “The Last Sea Cow’s Testimony” broke my heart to read. I thought of walking in the wake of serial losses in my life. I needed this poem. You write a persona poem in the voice of a sea cow conscious of its imminent extinction:

Now I am the last of the sea cows, my heart’s

continued beating, my tail’s propelling labor

my streamlined existence all become hopeless

An anticipatory grief rushed through me while experiencing this poem, which also read to me like an ecopoetic experiment in translation. What do you think of that?

Still on the last sea cow, I kept going back to your poem with Ed Roberson’s poem, “We look at the world to see the earth” from the collection, To See the Earth Before the End of the World on my mind:

We look upon the world

to see ourselves in the brief moment that we are of the earth

a small fern in the brief crevice of the cliff face

to see ourselves

in the brief moment

that we are

of the earth

I couldn’t look away from the perpetual precarity of what’s here, and what’s coming. As the poet Reginald Shepherd put it, “I have a strong sense of the fragility of the things we shore up against the ruin which is life.” Can you talk about your process regarding the poetics of scientific inquiry, flux, and extinction in your poems starting to find form, on the pages?

BK: It was conceived more as a meditation of what humanity has done to the non-human inhabitants of the natural world, and the consequences of human rapacity and action on those inhabitants. But a fundamental aspect of the poem is a judgement between species, the doomed and soon-to-be destroyed passing judgement on the destroyer.

Taking a deep-time perspective on life on Earth, it’s also been estimated that something on the order of 99% of all species to have ever existed are extinct. That figure of course ties into the phenomenon of mass extinction, but this is to say that in the long view of life on Earth, a species is a very ephemeral thing. Something very far from eternal when looking beyond a human timescale. So, there’s a baseline precarity facing all species on this planet. This is what the poem “Muskox Memory” touches upon—the flux of species appearing and disappearing–with the fossil record being a catalog of disappeared species. The ephemerality of species is also at play in “The Location We Look For.” However, the actions of humanity through climate change and habitat destruction of course are causing species to disappear at an unprecedented rate: for example, about 33% of living insect species are threatened by extinction, as are about 40% of living amphibians and 25% of living freshwater fish. Those percentages pertain to species scientifically known (i.e., taxonomically named and described); I should also point out that species are being lost before they can even be so recognized. So, our handprint upon the natural world is one of not merely coming, but currently unfolding, loss. This sense of loss informs my poetry by shaping its content and ideas, but beyond that I would not say I am working in or developing a poetics of extinction, at least not one in terms of any specific device or technique.

MT: I have been carrying “Eggshell Future” on my walks in town since I received your book. The person in the poem stops themselves before their foot accidentally steps onto four brown plover eggs:

the mother plover accosting me

in wingbeat panic, her rendition

of a broken wing both ploy and plea

to lure my human footsteps away

and safeguard an eggshell future

Was it a Common Ringed Plover? I was doing some digging about plovers on Ellesmere Island.

Reading this poem, I thought of your last sea cow, watching the life of its species go out, as I read and experienced your plover and their speckled eggs. Their wailing. Precarity streams through both poems, and through both species. The catastrophic asks all species for adaptation; is that at all right, or relevant? The plover’s wailing and the work ahead of protecting those eggs made me think of a couple things. First, partus sequitur ventrem–the 1662 legal doctrine meaning ‘that which is born follows the womb,’ and which established the mandate that children born to Black enslaved women would “inherit” that status. I thought of Black enslaved women, and their work of “safeguarding.” Are you familiar with Joy James’ notion of the “captive maternal?” James describes the “captive maternal” as “one who is tied to the state’s violence through their non-transferable agency they have to care for another.” Can you see that tie in the plover, guarding over the “eggshell future” of her young? How did this particular excursion on Ellesmere Island make its way into the collection?

BK: Well, I would say that the catastrophic demands that all surviving species adapt if their current anatomical, physiological, or behavioral traits don’t enable them to survive the catastrophe outright. And it could very well be that different species might have different responses to a catastrophe. However, a catastrophe might occur so rapidly that it’s impossible for a species to adapt apart from (maybe) a change in behavior. So while what you’re getting at sounds like it could be generally true, I think this is a hard thing to generalize about.

Sure, I can read the plover as tying into the concept of the captive maternal, as it’s subjecting itself to danger to care for its eggs. The reason this experience earned its own poem is because it illustrates using a very compressed scene how, even unwittingly, humanity imperils the natural world. At a more superficial level, the poem focuses on a living bird as opposed to a fossil, as in “Our Gilled Forebear” or a mammal, as in “Muskox Memory.” The other consideration is that since the other poems in the Dispatches section are on the longer side, I also wanted to include a more compact poem. At one point, I thought about incorporating the story of the extinction of the great auk into the poem. In short, once it was realized the auk was virtually extinct, a team went out to collect the last known pair of great auks. In the ensuing scuffle as they strangled the birds, one of the collectors unintentionally crushed the last egg of the species. After this tragedy, the great auk as a species was no more. You could argue that it was literally stomped into extinction. I opted not to touch upon this story in the poem, so as to keep the poem short, almost as a vignette, and to hold the story of the auk for a future poem.

MT: “Moqueca Chronicle” is a kind of voyage of one’s own, at a separate scale and temporality than “Natural History, the Curious Institution.” There’s a way the poem asks, or follows the inquiry, of how to live and move in slavery’s and natural history’s ongoing wake? What to take in feels like part of the speaker’s work to address, and cooking brings them in close contact with the past:

Two handfuls of crawfish tails throw in

a touch of my birthland

I spoon the moqueca over rice, and my plate holds

an heirloom from a continent estranged.

How were you thinking about history, or inheritance, in this poem, and section?

BK: Well, that particular poem evolved out of a challenge: can I develop a poem from a recipe? The thing is that I actually do cook Brazilian food, having started after my first trip there in 2016, and moqueca is perhaps my favorite Brazilian dish to cook, alongside vatapá and maybe vaca atolada (though I rarely cook anything with so much meat these days). The poem doesn’t give quantities of ingredients, but it does by and large follow Thiago Castanho’s recipe in the book Brazilian Food with my own modifications. My desire to take up this challenge stems from my urge to write about topics that interest me and experiences that are important to me. For “Moqueca Chronicle,” my interest in cooking, Brazilian food, and history, and the experience of my first trip to Brazil take center stage.

In terms of turning the recipe into a poem though, I think the idea came from knowing that dendê oil has its origin in West Africa, and the role of the slave trade in bringing that ingredient to the Americas. There was also this sense that, though I am not Brazilian, the transport of dendê oil from West Africa to Brazil is a reflection of a broader history that my ancestors are inextricably a part of. From there, I started to contemplate the history of the other ingredients in the recipe. And out of that grew the realization that a recipe is a chronicle of world events and a point of intersection for different histories. So, in a very odd way, you can argue that a recipe’s ingredients comprise a kind of museum that tells a story on multiple levels, in terms of the story of each individual ingredient in world history, the story of the recipe itself and how those ingredients came together, and the stories of how recipes are passed on and intertwine with our personal lives and histories. When recipes are passed down or otherwise disseminated, these embodied stories and histories are also passed along as a form of inheritance.

MT: “Natural history” as a realm of inquiry has its own morphology. What starts as observing essentially anything in the natural world seems to shift by the 20th century toward direct observation of organisms in their environment. Which prompts my curiosity about observation in terms of your poetics: what is it like to practice seeing, for you? And can you talk a bit about your ongoing relationship to natural history, and share a bit of the morphology of your own relationship to inquiry, scientific or poetic? In “Natural History, the Curious Institution,” you shape a trip across the ocean using historical events and illusions. About the institution of slave trading, the museum, or beyond–how capable are our institutions of curiosity, or of wonder?

BK: It’s funny that you use the term morphology—as the study of limb skeletal and muscular morphology is the central theme of my research. For my research, observation and, consequently, image is key. Among my first research experiences was the redescription of a dinosaur skeleton, an armored dinosaur named Gargoyleosaurus in 2003, and an anatomical description is first and foremost a close visual inspection. But before this, I was always fascinated by the anatomy of animals, even as a child. My later research relied on collected data (i.e., observations) from the bones and musculature of limbs using calipers and scales. And these days, my research relies a lot upon CT scanning, so as to visualize the interior contours and structures of bones without having to physically damage specimens. My research is also largely comparative in nature, using comparisons among species to make inferences about evolution among lineages of animals. To communicate this to other scientists, making figures to illustrate findings and interpretations of the results is essential. So natural history is very much a visual endeavor for me, and collecting data is ultimately an act of making observations with regards to museum specimens.

Observation and comparison are likewise key devices of my poetry, in the form of imagery and juxtaposition. Particularly to show hidden histories, to show the human consequence of past practices, I rely upon imagery. To show the dual side of wonder, I use juxtaposition, which I guess you could say is a kind of comparative method in poetry. For example, the poems “The Giraffe Titan (I)” and “Natural History, the Curious Institution” rely upon juxtaposition to make their arguments. Likewise, because dioramas are visual exhibitions, and there is a certain kind of drama staged in their composition, depicting dioramas in poetry calls for strong imagery.

But to go back to your broader question of seeing, the work of writing about hidden histories is at heart an act of seeing, an act of witness, which is essentially an acknowledgement of what has long been—deliberately or indeliberately—forgotten, ignored, or dismissed. The situation that these histories have long been cast aside or gone unacknowledged by institutions and the discipline at large compels me, especially as a Black person in the museum sphere, to engage in the acts of acknowledgement that are these poems. I should say that now knowing these historical events, I can neither unsee nor forget them—they are fundamental aspects of the history of natural history. They have shaped the present state of museum-based scientific research and museums themselves; moreover, they in many ways reflect bigger geopolitical histories. So as much as museums have been a part of me, and my wonder toward the natural world has been a part of me, I have to at the same time grapple with these histories and their lasting legacies, make some attempt at reconciling this wonder and the inhumanity instrumental in producing them. The topics of colonialism and slavery and their role in the development of natural history and museums is starting to gain greater visibility among natural history museums, and I think this will continue, so long as the museums, universities, and their staff remain curious about the pasts of both their institutions and fields of study and open to reflecting on them. Or so I hope.

MT: Your dioramas in “Dioramic Idylls” led me down a bewildering line of inquiry, questioning the relationships between the “poem” and the “diorama,” both of which are or can be ‘lifelike representations,’ and both of which can hold the peaceful or picturesque sense of the “idyll.” Both the diorama and the poem both take part in what you describe as these “facsimiles of living.” The history of the diorama (at least its etymology) seems young to me, a couple hundred years old . . . at least young in relation to the Devonian environments depicted across your poems in the third section, “Dispatches from Ellesmere.”

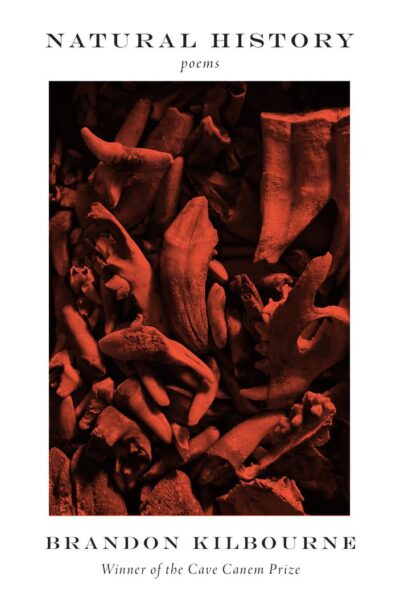

Is it relevant to you to see the diorama, or your poems, as being in service of “a biological story?” The word diorama itself comes from the french diorama, then from the greek dia “through” + orama “that which is seen, a sight.” Between the naturalist’s imperative for observation, for direct ways to “see” species interactions embedded into the environment, what are some of the ways you think about “seeing” in these particular poems? Can you think out loud with me about how the “diorama” lent a sense of structure or form to your poetry sequence? Can a poem be a diorama, or move like one? (Ekphrasis also seems to run in the background of this question, and of my curiosity . . . but no pressure to share anything about the cover, in particular, and how it participates in this project?)

BK: Dioramas are certainly young—as is the whole of human history—compared to the Mesozoic and Devonian environments that are present in the first and third sections of Natural History. I am not sure if I would say that my poems are intended to be in service of any biological story, though I think that’s an interesting idea for a couple of reasons. My poetry does try to share my interest in and wonder toward the non-human world with readers, with the hope of fostering in them that interest and wonder, and a curiosity to learn more. This I’d say is no different from a scientist trying to share their interest and enthusiasm with their students, lab trainees, and the public. The other thing is that for some of the poems—such as “Rhinoceros Relic,” “The Last Sea Cow’s Testimony,” and “Our Gilled Forebear”—I try to present non-human entities, I mean species, on their own merits and not in any explicit relation to human needs or concerns (apart from arguably the desire they not go extinct if still extant).

I don’t think the poems are intentionally structured as a diorama, though I know individual stanzas strike some readers as dioramic. I tend to think more in terms of scene, particularly of a stanza as a scene. What is a classical diorama but a scene? I would say, though, that each section of “Dioramic Idylls” was seen as being something of a diorama. I mean, certain sections specifically focus on individual dioramas, with their specific basis coming from the dioramas at the American Museum of Natural History in New York. “Rhinoceros Relic” is also a poem specifically about a diorama, now dismantled, in Copenhagen. In some ways, the couplets in that poem work toward a diorama, as they focus on the physical form of the rhinoceros. At the same time, each of the nine-line stanzas has a kind of self-contained focus. So, to the essence of your question, a poem can easily function as a diorama, if you consider a diorama as ultimately a scene. Going from section to section, or from stanza to stanza can be analogous, I suppose, to going among alcoves in a diorama hall, such as you see in museums in New York, Chicago, or LA.

Despite trying to stick to the facts, I hope presenting them in poetic terms can open new spaces to reflect upon that information and engage with these species and the natural world more broadly. To me, there are parallels in the role of seeing in both science and poetry. The scientist’s works strive to give new insights and understandings about the natural world, and the tools at her disposal in this task are as various as anatomical dissection, microscopes, telescopes, CT scanners, cineradiography, and camera traps, among numerous other devices I’ve most likely never heard of. For the poet, the goal is more to provide insights into human experience, regardless of whether that experience is firmly entrenched in the human world, the more-than-human world, or somewhere in between. So the poet has to find a way to engage with the reader to impart these insights, to renew human experience or perhaps open up new dimensions in understanding it. The tools available to her include imagery, metaphor/simile, allusion, alliteration, rhyme, syntax, diction, persona/voice, poetic form, and volta/turn, amongst other devices not coming immediately to mind. All these devices are in the service of “seeing” in the world of a poem.

MT: To veer slightly from the exhibit, I have a question about what it’s like to experience. I wonder also about the visitors who move across some of the poems in Natural History, and also about your sense of a reader moving through the collection? Do you think about your writing or your scientific inquiries at all as a curatorial practice, for visitors or readers?

BK: Well, I think science and poetry, at least at some practical level, are a curatorial practice, whether you want it to be so or not. You cannot write everything. Much of poetry draws upon a compressed form. So for any kind of narrative or fact-based work in particular, there has to inevitably be some kind of curation—not every fact, whether in terms of natural history, human history or biography can be included. Likewise, not every aspect of an experience can be recounted. Otherwise, the poem is bogged down. So it’s a matter of finding what’s essential. Likewise, in science, it’s a matter of keeping your discussion of the results really to the topic at hand, otherwise, you might have a discursive mess on your hands that no one in your field would be eager to read. The narrowing down of a research question or refining of a hypothesis, in a certain sense, is a kind of curation of inquiry. In poetry, this would be tantamount to figuring out if in a draft you have two separate poems starting to take form that need to be pulled apart into separate works. Determining whether you have one or more poems in that draft then depends upon—at least in my experience—asking what you are really trying to ask in the poem and refining that question.

With regards to museums, it’s worth noting that the exhibitions themselves represent an action of curation—typically, less than 5% of the collections in the bigger natural history museums are on display as exhibitions. Sometimes much less than that.

MT: There are some poems that feel like portals, of sorts, that shift our attention from the dioramas to the fields, however empty they may be. One example of this transport is the poem, “It Came from Beneath the Sea,” where you write: “As I pore over the animal in my hand, / I flash back to my childhood home’s garage.” Can you talk about the oscillations in this first half of the collection, between the speaker’s movements and attention in the realm of the museum versus the museum of their memories: “the menagerie of my coloring books escaped from their pages / to steer my life’s course to these bones in Berlin”?

BK: I think this question comes down to my sense of place within my poems, what some would go so far as to describe as world building. Just as place is central to my experiences and memories, so too is place central to a museum diorama. As I mentioned earlier, there’s a sense of “scene” in my work, and what I think you’re hitting on, in terms of attention, is the act of close observation of a scene. In the diorama, the viewer has ample time to take in details that make the place. In recalling memories, a person has the time to take in the details that inform the memory, whether it be the actions of another or the minutia of location. So the act of reflection can be something akin to close “observation” of memory. At the same time, I would say that the classic dioramas, the ones you see in the American Museum, the Field Museum, the Bell Museum, and the Los Angeles County Museum, offer a kind of memory of an idealized, romanticized nature somehow not only untouched by, but completely independent of, humanity (though how did those skins, leaves, insects, etc. get inside the museum . . . ). And I’m saying that as someone who has a soft spot for such dioramas. I guess the thing is that human memory is not 100% reliable, whereas those dioramas, and the memories they represent—whether real, romanticized, or fictional—really do never change.

So a common thread between the first two sections of Natural History is the emphasis of place, or scene, though that’s true for the book as a whole. Another common thread is the role of a scene in telling a story. Museums certainly carry a narrative in their exhibitions, diorama or otherwise, and similarly my poems carry a narrative or storytelling element. And you can look at the difference between the first two sections of the book as being between narratives maintained in museums and a Western perspective on the natural world vs narratives maintained in personal memories. But as I’ve been critical of narratives in museums, perhaps it’s only fair to be a bit critical of the speakers in the section Memory Museum. In saying that, I don’t mean any intentional deceit, but it’s a question of blindspots in the stories told, or a curation of what facts and details are deemed important to a story.

MT: In “The Charcoal Speck,” your speaker notes privately, “I have the valley to myself,” though not for long. Later in the poem, realizing that all along a charcoal speck–“a fox furtive in its seasonal color”–is gazing back “from a blind of hillocks and hollows.” The speaker ends their observation watching the fox’s:

offward

slinking form like a brusque reproach

of my presuming for even a second

that I had this valley to myself.

That moment, where one has the valley to themselves–is it desirable? A compulsion? What is the libidinal and/or possessive character, if any, of this poem? I am wondering about the inclination to “have” or “own” in these poems, and in the slave trade’s wake, whether that lends itself to compulsion, to what it is to be a social yet territorial species, and beyond. How do you think or practice poetry, with your relationship to ownership–and even to a self–in mind? I found this poem, like “Eggshell Future,” brave in its willingness to express an entangled, and potentially harmful, participation in one’s environment.

BK: I would say it’s none of the above, actually. As I conceived it, this poem is more about anthropocentric arrogance. But I think you are on to something in the desire of humanity to possess or consume the natural world. To me, this is something tied to a species-level self-centeredness. In “Eggshell Future,” there is more a species-level absentmindedness at play than a self-centeredness. So in terms of both humanity’s self-centeredness and absentmindedness, the natural world is imperiled. Personally, I wouldn’t look at these poems in the context of the Transatlantic Trade, though self-centeredness and absentmindedness contributed to the barbarity and dehumanization inflicted upon the enslaved. I would look at these poems more in the context of Terra nullius—No One’s Land—the supposedly unoccupied land open to claim and settlement by Europeans looking to establish colonies. Of course, those lands in Australia, the Americas, Africa, and elsewhere were a far cry from being unoccupied, but the mindset, if not the concept, of Terra nullius was very convenient, offering a self justification to enter into these lands with a sense of entitlement accompanied by self-centeredness, absentmindedness, and, yes, possessiveness. I don’t think I have to go into how this assertion of being in unoccupied land has had devastating consequences for both indigenous communities and the environment.