Interview// “On Interbeing and Sleepwalking Towards Extinction”: A Conversation with Harryette Mullen

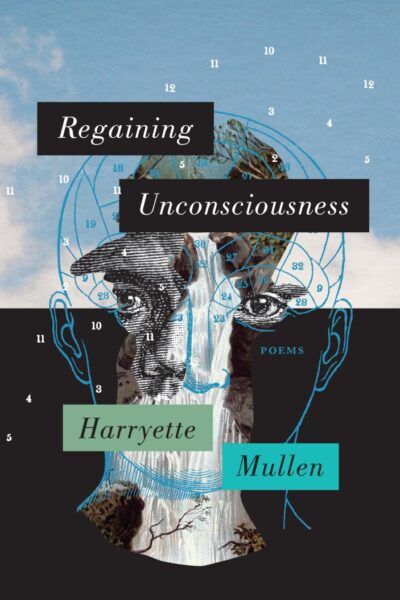

In eleven sections collaged with both play and sharpness, Harryette Mullen’s Regaining Unconsciousness (Graywolf Press, 2025) is a generosity amid the world’s flux. In the midst of apathy, corporate consolidation, extractive and degrading economies, and the ever-growing distances between us, Mullen’s poems both yield to what’s coming while imagining what’s possible. We met briefly at this year’s Cave Canem retreat(!), where I sat humbled and tingling with what I might ask, when the time was right. Mullen was kind enough to sit with a brain and heart full of questions. Her responses and poems have been both generative and quieting. As the seasons turn, may the following conversation offer levity, curiosity, and responsiveness amid the gravity of where and how we are. Harryette Mullen: thank you.

*

MaKshya Tolbert (MT): In one reading I have of your work, Regaining Unconsciousness reads to me as a very long day in the midst of an ongoing yet precarious existence. In the opening poem, “Was it a dream?” you start each stanza with, “Was it a dream” and “Was it a durable dream,” respectively. The latter sweeps my attention both forward and back, back into the dream or out into the waking world. In one sense, one is ‘awake’ and wondering if they’re coming out of a dream, or perhaps if their existence is one? In another direction is the question of the dream’s quality of ongoingness. The dream one comes out of, or perhaps into another existence. I began thinking about what it is to keep a dream alive in one’s waking world, or not. About its carrying capacity. Can you talk about how you set out to begin the book, or what the invitation was in starting this way?

Harryette Mullen (HM): Thank you for that attentive and generative reading of an opening that poses questions the poem doesn’t answer, but leaves for the reader’s contemplation. “A very long day in the midst of an ongoing yet precarious existence. . . . The dream one comes out of, or perhaps another existence.” I think your proficient summary of this book applies, as well, to the way many of us are feeling as the fragmentation of social order converges with the anthropogenic collapse of ecosystems. I’d hoped to involve the reader in exploring questions that may be perplexing. Do we snap awake in the latest emergency, only to lose awareness of the approaching cataclysm, the moment “the fire is contained” or “the shooter is neutralized” and we feel safe again?

MT: In part, your new, wondrous book is described by your publisher as “eleven taut sections written in the eleventh hour of our collective being.” I’m wondering about urgency, the collection’s relationship to time, and also about how concepts of the self might morph across Regaining Unconsciousness. Time-wise, we’re running out of it. Eleven sections of ecosocial uncertainty, of this running, smoggy feeling that there is much to shift or else. I read some poems as aptly at the eleventh hour, and in other poems I read a kind of ‘fugue,’ or preparation for flight or flux, as much as I read saving time. A few poems where I noted this include “Wake Up, Butterfly,” “Bomb Cyclone,” and “Dark Pattern.” Geologist Marcia Bjornerud suggests that one way to see time is “as the earth itself.” What do you think about the notion that these poems both prepare to shift (if in somewhat self-preserving) ways in the face of catastrophic changes, and also prepare or yield to individual or collective transition?

HM: According to Bjornerud, we could rescue Earth if we thought more like geologists, expanding our sense of time beyond human history and thinking in terms of earth time or geological time. We tend to be rather shortsighted, with a narrow focus on our immediate needs, here and now. In my poetry, among other things, I’ve tried to imagine Earth before humans existed and after we cease to exist. Perhaps, we don’t deserve to continue as a species. Nevertheless, I want us to survive the damage we’ve inflicted on the planet and I want the planet to survive our abuse. I pray we still have time to change our ways and save the world.

MT: Back to the part about the self, the other arm of my question about urgency and each other. Your new poems got me to go down a briefly medieval path, wondering about this notion that to some, there was a “permeable self.” Author Barbara Newman explores this more porous and vulnerable sense of self in her book, The Permeable Self. I’m wondering how you think about the self (or our collective being) and its relationship to environment, or an amongness, across the collection? How porous is the world of Regaining Unconsciousness?

HM: As a point of reference, I lean toward “interbeing”—interrelatedness and interdependence that connect the individual to all of creation (human and other)—as I understand the work of Thich Nhat Hanh. It supposes a more expansive and interactive sense of being in the world beyond a separate, isolate self or psyche. Literature can connect us cognitively and emotionally to people we might never encounter in our daily lives, but we also need physical and social connection. Our survival depends on cooperation with others. Newman’s interest is cultural and religious models of personhood, but our bodies literally are penetrable and permeable. Biologically, we support trillions of other life-forms on every surface of our bodies, inside and out. I didn’t write about the biome in this book, though it makes a brief appearance in Sleeping with the Dictionary, with “Resistance is Fertile.”

MT: I see the scales jump in your work. What I called one long day with uncertain yet little time left can just as easily jump the scale into a commentary about the longue durée of our contemporary existences. Still, patterns emerge. When I think about environment, expressiveness, and intimacy in your work, Baraka’s “changing same” comes to mind. How do you think about patterns, or ongoingness, in this book? I read your poems as a pressure valve being released in the middle of our patterns and decisions—traffic, bad air, our refusal to give more of ourselves—as our environments and relationships shift and recede.

HM: Yes, the different time scales might vary from comprehensible to incomprehensible; from one day in the life of an individual, to an entire span from birth to death, to our collective existence as a species, to the lifespan of this lonely planet. A billion years might as well be eternity, but we have the means to destroy ourselves instantly, or make Earth virtually uninhabitable even if we don’t blow ourselves to bits. I’ve observed how persistently, in our biologically and psychologically driven states of consciousness and unconsciousness, we seem to forget and need to relearn what is essential for life to continue.

MT: In both poetic form and practice, I’ve been wondering about my own ecopoetics, which are as much in flux as environment is, and as I am, I suppose. Prose poems could be, maybe, a poetic form for flux, for one-thing-after-another. How are you thinking about the morphology of your prose poems across the collection, which itself anticipates several kinds of lives, or endings?

HM: A prose poem is a versatile container for all sorts of things. It is a protean form, capable of sampling multiple genres, such as storytelling, diary writing, letters, reports, essays, jokes, anecdotes, and aphorisms.

Critical readers sometimes disparage certain free-verse poems as “prose with line breaks.” Versification, composing poetry with systematic breaks for lines and stanzas, lays out a visual structure that readers can apprehend at a glance, noting patterns and repetitions as they scan the text from top to bottom, left to right (in English, at least). However, I have witnessed in the classroom, and even in dialogue with copy editors, that readers can’t always distinguish free verse in long lines from a prose poem with a ragged right margin. Line breaks, with carefully selected end-words and a deliberate mix of line endings (stopped, paused, or enjambed), are meant to call attention to the poem’s pace and rhythm as well as the poet’s choice of emphasis while managing the reading experience.

Breaking lines creates more places to put important words, but I notice that people who don’t often read poetry may be baffled or intimidated by the spatial arrangement of words, lines, and stanzas, particularly as verse structure may be in tension with the grammatical and syntactical flow of sentences.

Regaining Unconsciousness, like Sleeping with the Dictionary, incorporates both free verse and prose poems. Urban Tumbleweed collects unconventional verses from my tanka diary written during a year of walking—mostly in Los Angeles—while Open Leaves alternates haiku with passages of poetic prose. This latest book includes visual poetry, along with my adaptations of traditional forms such as ghazal, sonnet, ballad, haiku and tanka. Several prose poems were written as entries in a catalogue of meteorological phenomena with names, new to me, that eventually became familiar, repeated in weather reports: atmospheric river, bomb cyclone, derecho, pineapple express, and polar vortex.

MT: Is your ecopoetic attention shifting and expanding? If so, what are some of the patterns or practices that guided writing this collection?

HM: I’m more aware that lack of respect and care for diverse expressions of humanity goes hand in hand with other toxic behaviors, leading to ecological destruction and avoidable suffering. A frequently cited example is the policy of dumping waste in areas where poor people live, distant from enclaves of privilege. Can we imagine a future in which we all live well without ruthless exploitation of human and other resources? I’ve taught a course at UCLA, originally titled “When Black is Green,” using Camille T. Dungy’s anthology, Black Nature, along with essays by various authors collected in Erin Sharkey’s A Darker Wilderness. That’s helped me to think, along with my students, about challenges to individual and collective survival that we all face.

MT: I’m curious about how your attention and poetics are shifting, in terms of your haiku poetics, and how you chart out an oscillating relationship to language and environment, in there? Are your poems or processes changing in flux, too?

HM: I had been reading traditional Japanese poetry (in translation) long before I began to write tanka or haiku, and I’m aware that mine don’t conform to that tradition. Sonia Sanchez encourages poets to write daily haiku, traditional or not. My tanka diary, Urban Tumbleweed (Graywolf, 2013), was followed by haiku and prose poetry in Open Leaves / poems from earth (Black Sunflowers, 2023). As I’ve continued to work with haiku, the 17-syllable format is a way to write stanzas that are grammatically, syntactically, and thematically connected within a poem, as well as poems made by collecting haiku composed over time as separate verses, similar to how I’d written daily 31-syllable tanka in my journal.

MT: I once asked about the relationship between the kigo (a season word or phrase often indicating the verse’s season) and an environment in flux. I was wondering about how the kigo shifts as the tree canopy or our habitats and communities recede? In your haikus, I got a sense, maybe, that the kigo thins, or perhaps that its presence is hidden in plain sight. How do you think your uses of these “season words” (or not) entangle with the collection’s ecosocial atmosphere? How do or could ecological or environmental conditions generate or challenge a sense of what a season word can be?

HM: Urban Tumbleweed includes several tanka alluding to seasonal transitions marked by what produce is available in weekly outdoor farmers markets that are held in nearly every Los Angeles neighborhood. As I wrote in my preface to that collection, California’s seasons are specific to our region. Phenomenal weather varies from the hot and dry Santa Ana wind to the wet and wild Pineapple Express. Like everywhere else, our seasons are becoming more intense. More rain, more flooding, more heat and drought, more fires. We used to have what we called fire season; now wildfires might ignite at any time of the year. Quite a few poems in Regaining Unconsciousness respond to the increasing frequency of extreme weather events that upset our expectation of regular or predictable seasonal changes.

MT: Okay—just one more haiku question—then we “can talk about environment,” too. I am thinking of Lucille Clifton’s lines:

being property once myself

i have a feeling for it,

that’s why i can talk

about environment.

I have been self-apprenticing to the Japanese concept of mono no aware as part of a broader commitment to haiku and contemplative poetics. I’ve seen this translated in English as “the pathos of things”; one’s capacity to live through an ongoing awareness of the transience of things and to hold the “gentle sadness.” You write, “Love needs love today— / as far apart as we are.” How relevant or near to this tenderness is your writing practice?

HM: Haiku stanzas in Regaining Unconsciousness were mostly written during the COVID-19 pandemic, partly overlapping with haiku collected in Open Leaves. Several were prompted by songs or paintings, or by walking in the neighborhood to escape indoor confinement. Trying to compress expansive feeling and perception into a mere seventeen syllables reminds me of all that escapes our grasp in the measure of a moment, a day, or a lifetime. A poet tries to do what’s impossible. It’s worth trying even if we fall short.

There’s a poem by Toi Derricotte that I recommend to students as a contemporary example of carpe diem. While it dwells on apprehending the present moment, it has that “gentle sadness” rather than the seductive rhetoric of Marvell’s speaker addressing a coy mistress. Derricotte’s poem begins:

I went down to

mingle my breath

with the breath

of the cherry blossoms.

It concludes: “You have an ancient beauty.” The brief life of a cherry blossom reminds us to appreciate our own transient existence. Yet, as we mingle our breath with the blossoms, we share their “ancient beauty.” It’s an engaging image of interbeing.

MT: This is a long one. Thanks for your patience. There is an abundance of atmosphere in your poems, and the weather changes: it pinks, goes bad, and wears on us and species around us. Like you say in “Weathering Hate”: “The way, exposed to weather, a body is worn.” Human bodies, bird bodies, and cultural bodies all come to mind. I hear in your work both standard definitions of weather (v.): “to wear away by exposure to weather” as well as “to bear up against and come through safely,” (Online Etymology Dictionary). While reading Regaining Unconsciousness, Marvin Gaye’s “Mercy, Mercy Me (The Ecology)” came to mind. The song’s first verse has a few lines that go, “Where did all the blue skies go? / Poison is the wind that blows.” Gaye’s 1971 album, What’s Going, converses (in my mind, at least) with Regaining Unconsciousness, as does Christina Sharpe’s In the Wake. I read much of your book thinking about Sharpe’s sense of anti-blackness as “weather,” as “the atmospheric condition of time and place.” For Sharpe, the weather “necessitates changeability and improvisation.” And for you? With all that said, how do you or how can we in our conversation think about the atmosphere of Regaining Unconsciousness? Is there a relationship or inquiry that interests you, between the degradation of our shared air and the morphology of one’s inner life or shared sense of self, in this collection?

HM: With the existential crisis of climate change, atmospheric conditions influence metaphors we use in speech and writing. Public health researcher Arline Geronimus has been developing her weathering hypothesis since the 1990s, culminating with her book, Weathering: The Extraordinary Stress of Everyday Life in an Unjust Society. Likewise, Sharpe’s In the Wake employs environmental tropes to observe the pervasive effects of social injustice. Their writing follows the poetic lyrics of African American spirituals and gospel music: “I’ve been in the storm too long.” I’m thinking of climate both as metaphor and as physical reality, an unavoidable fact of life-and-death. I’m thinking of “weather” as subject and predicate; as a double-edged contranym meaning to survive as well as to be damaged or ruined by external forces. “Weathering Steel” and “Weathering Hate” address those contrary significations. Will we survive the weather, or not? Will we move beyond the willful inertia of leaders in denial, still debating whether or not? In current colloquial usage, Gaye’s blue sky might refer to thinking creatively, keeping an open mind, or holding overoptimistic opinions. As Sharpe indicates, innovation necessarily follows difficult weather. I find room in my work for variety, spontaneity, and improvisation, embracing their practice as survival skills.

MT: Forms of entertainment and sarcasm are embedded into Regaining Unconsciousness, probably as much as in our relationships! Where does wit, irony, or something entertaining to watch or laugh, meet the worry and anxiety that underlies the poems? And the funny? I’m thinking about “Chili Today, Hot Tamale,” where you write, “We only wanted cheap, fast food—and plenty of it.” “Sharknado” and “LUVTOFU” come to mind, too. These poems got me thinking about poet Nuar Alsadir, who writes about there being two studied kinds of laughter—an unconscious laughter sourced from a deep sense of aliveness, and a social, intellectual laughter used to control interactions. A spontaneous, animal-like joy, or something more reactive, perhaps more anxious. How did you set out or intend a sense of humor for the collection? Is there a laugh you were after, or over? In terms of motivational forces, do your poems seek out one form of laughter more than another? Are we giving up, sometimes, on the “animal joy,” and falling back on the laughter we feel we have? What comes up, humor-wise? Can we have a ‘good’ laugh and an anxious laugh, with you, and in the collection?

HM: I suppose, for readers, there might be moments of anxious laughter, the way I sometimes laugh when I catch myself behaving in a way that’s not in line with my ideals. Alsadir said, in a conversation with Cathy Park Hong, “sometimes when we laugh it’s because we recognize something.” That’s what I’m aiming for, rather than laughter or humor for its own sake. I’m not really trying to be comical. I’m just looking at things from different angles to find that point of recognition. For me, it might begin with an unexpected collision of words and images, a fractured allusion, or a pop-culture mash-up that goes in a different direction than the originators intended. “LUVTOFU” might come closest to joyful laughter. It started with an amusing news item and ended in a way that surprised me when I wrote it. I will admit that, when listeners laugh, I’m reassured that my reading hasn’t put them to sleep.

MT: When we met briefly this summer, you welcomed me reflecting on working toward a clarity about what drives my writing and poetic inquiries. Since then, I have been wondering about your own sense of process, clarity or otherwise. Are you willing to share a bit of how you worked toward a sense of clarity about putting Regaining Unconsciousness together? What, for you, has driven your writing process with this latest book?

HM: I often begin with the opposite of clarity: vague notions, uncertainty, confusion, or questions. Are we just tired of living? Are we willing to work together for our collective survival? Are some of us resigned, or looking forward to the end, because we imagine it will hasten a new beginning—a post-apocalyptic future without flawed humans? The only thing that’s clear, when I’m beginning to write, is that I want to find out where my thoughts are going, and follow them wherever that might be. It’s the process of writing that guides my thinking as I go, often starting with just a few words that I play with, moving them around in my mind, in my mouth, and on the page. I tend to generate lists of titles and possible lines that I use as prompts for new poems. Plausible book titles don’t happen until rather late in a project, usually when it’s more than half done, and choosing a title helps me to clarify the “mission” of the book, if I can call it that. It contributes to my thinking about the work as a whole, its overall organization.

As I write, I’m reading and revising, thinking how one word might relate to another, and how to write so that there’s more than one possible meaning. It’s not necessarily that what I’m writing is always clear. What’s clear to me is that, at a certain point, I am committed to finding my words as I’m thinking. It’s the process of writing that teaches me how to write a poem that, ideally, will teach readers how to read it. What I write becomes clearer, at least to me, after I’ve written it, and often after I’ve shared it with others.

Regaining Unconsciousness began with my fear that we are sleepwalking toward extinction, set on a path of destruction. In the poems, I contemplate two aspects of this dilemma: the ongoing threat of climate disaster and our seeming inability to face the challenge of rescuing ourselves and all other life on the only habitable planet we know.

MT: I wanted to end on how you bring the book to a close. The final poem, “Thanks to,” opens with gratitude for “fresh clean sheets line dried in sunshine.” The catalog of thank yous calls to mind a person with a nightly gratitude practice. (Are you a person who has that?) I found it intriguing to end a book of poems anticipating the end of the world by offering thanks to “faces of gentle strangers I may never meet.” There’s a kind of yielding, to the time and life one has or doesn’t have. To bring Regaining Unconsciousness and our conversation to its end, how did you search for a satisfiable place to set things down as our existences continue their coming together and fragmentation?

HM: I wanted to write about serious matters in a way that isn’t hopelessly bleak and depressing. We can’t just give up and do nothing. We need to oppose and resist the people who are driving us to destruction. I believe in trying to save ourselves, even if we fear we’re not worth saving.

I do remind myself often to say thanks to life, and to thank the people in my life. I had the opportunity to hear Mercedes Sosa sing Violeta Parra’s “Gracias a la vida” in concert, and it has stayed with me ever since. We must value our own lives and the lives of others to act so that life can continue on Earth. That is my hope.