Interview// “On the Fleeting Natures of Here and Elsewhere”: A Conversation with Mai Der Vang

In her new collection, Primordial (Graywolf Press, 2025), Mai Der Vang expands the definitional premise of belonging from a question of presence, to one that is equally interested in, and dependent on, absence. Drawing on the primordial light and language as a collective origin, her poems conjure the Saola as a body that might be able to approach and retain a place that only exists in an elsewhere; the Saola, a body that recounts language as both inflictor and, potentially, healer, of the compromising dynamic of imperialism that leads to endangerment and loss of homeland. Given that the Saola is the only species of its genus, when referring to this bovine, we chose to capitalize. I had the pleasure of asking her these questions via a Word Doc.

*

Alexa Luborsky (AL): Starting with a long multi-part question here, forgive me! “Primordial,” etymologically speaking, means to exist from the beginning, which to me is synonymous with “the word.” I mean this in the sense of “Logos” as Heraclitus was thinking of it. A form of balance, which Li-Young Lee has related to the concept of Taiji, that naming a word creates the presence of something via the absence of another. I was especially drawn to this logic in “I Understand This Light to Be My Home” where there are fragments that intercept circles formed by repeated words. I see this especially when you write, “Light as first / language of source.” I was reminded of this dynamism in opposites as I moved through this sequence. You write:

I stare to heaven and

weep for

stars whose light I have always known

and understood to be my rooting.

I started to think of these circles as spheres of stars that once existed, where each one is like a layer of a time we might have seen. And, because of how these fragments intercept these circular typographies that repeat the word “language” and “light,” I was thinking of language itself as the sky and the absences are the lights of the stars that have most likely already died in the astronomical sense.

To me, what you say about rooting is so beautiful because it speaks so sharply to the diasporic experience wherein to be able to see the location of homeland is to see its absence. Then eventually, the absence becomes the definitive/definitional space of home, just as light replaces language as we move along in this sequence. In Armenian, when we say “what’s up?” it translates to “what is there not there?” which I’ve always interpreted as a way of saying, “for you to tell me how you are, you have to tell you what you’ve lost.”

So I want to start by asking, what is the relationship between language and light to you? Either in the context of the poems themselves or for you personally as an author. And, secondly, in this sequence you say: “light is prehistory.” What would you say “history” is? Lastly, can you tell me a little bit about the title and how it came to you? Maybe how it relates to this portion of the book in particular if you’d like, which turns, formally speaking, from the rest?

Mai Der Vang (MDV): You’re right to draw connections between the “light” poem and the possibility of a larger primordial energy. The notion of the beginning of light in our solar system, the galactic clashing of interstellar substances that led to our planet’s habitability, and the creation of our sun, alongside the idea of language as a means from which we begin to know ourselves, hear ourselves, speak ourselves, and perhaps even reclaim or restore ourselves, are for me concepts that intertwine with a personal and collective sense of origin. Against the backdrop of what we can learn from physics and astronomy, I also want to believe in the existence of a larger primordial spirit that allows us to channel the ancestral and feel an interconnectedness that transcends the physical. Maybe I’m also thinking about the time before time and a prehistory that doesn’t exist on a linear scale. That’s a lot to wrap one’s mind around, but that’s probably why poetry has been a force in my life as a medium through which to reconcile the relationship between language or linguistic matter and my own existence.

The word “primordial” became an anchor for me as I muddled through these ideas. I thought about Saola and its connection to a primordial awareness that is both ancient and fleeting. As a rare and critically endangered animal endemic to the Annamite mountains between Laos and Vietnam, Saola looks like an antelope with its two long horns, but it’s a relative of wild cattle and buffaloes. Its features, specifically the large maxillary glands on its face, were unique enough that it was placed into a genus of its own where it is the only known member. I think of Saola as an animal that came to us from another place and time and who likely carries a wellspring of primordial knowledge. But the last known sighting of a saola was in 2013, so it’s possible Saola could already be extinct and altogether lost to our world.

On the note of loss, the Armenian translation you share is fitting and poignant. To know oneself and another through loss has a profound way of giving value and respect to what has been lost. We are everything we have lost as much as we are everything we have found.

AL: I’d love to hear about your use of pronouns to navigate the proximity between speaker, audience, and Saola. Up until about the end of section two, the “we” refers to the speaker and Saola, with Saola as recipient of the direct address “you.” In the third section, the direct address shifts to the audience. “In the Year of Permutations,” the direct address is turned towards the reader to expose the fallacy of binaries that allow for empire: “you over me, you think.” Then, in the series “Saola Grows Up in California: Daughter of Hmong Refugees,” the “you” returns to the Saola but this time it is also the reflexive “you” of the speaker. The pronoun collapse to me was notable and takes time to get to.

At this point in the collection, I was kind of assuming we wouldn’t see this kind of joint-categorization of speaker and Saola. I’m curious if you could speak a bit about that and maybe about what order you wrote these poems in versus how they have been compiled in the book? I’d also love to hear about how you negotiated the shape of these pronouns in relation to, or maybe better put, in opposition with, “otherness”? And, if you’d like, what does distance do for you as a writer and did this maybe feel like a way to avoid the stagnancy of a perfectly linear metaphor between speaker and Saola and/or Hmong and Saola?

MDV: I typically draft a poem in the first-person voice. It often helps me get the poem going as I try to figure out what might be bubbling up to the surface. During revision, I might change the voice to second and third person, sometimes even first-person plural, to hear the poem in a different register or perspective. It’s a practical revision matter, of switching the pronoun with a different one, but the effect can be significant.

For the “Saola Grows Up” series, I wrote these pieces initially in first-person, and when I rewrote the poem in the second-person “you” voice, it unsettled me, perhaps even troubled me, to hear the reflexive version of the speaker, or of myself, mirrored in Saola who was then mirroring itself back to me. As an animal whose circumstances seem to parallel the refugee, of fleeing and hiding in the midst of war, of being hunted and surviving against the odds, and of an overall precarious existence, it was unusual but also somewhat fitting to think of Saola as a refugee or as a descendent. There are ways in which the speaker, refugees, and perhaps even Saola exist in a state of “otherness” and the “you” provides a direct address that demands attention and clarity. The distance created by the “you” also has a way of disrupting the linear relationship that a reader might come to expect which I think can help jar the reader awake in that moment.

As to the order, I wrote these poems as they came without a particular set arrangement in mind, but I knew I wanted to position this series later in the collection as by then the reader will have been introduced to Saola and to Hmong. In writing about Saola, I also considered the ethical implications involved with writing about a critically endangered animal. Saola is real, Saola exists, and who am I to try and co-opt this animal into a metaphor for my art? I’m nothing and no one to do that. That’s also why, bizarre as it sounds, I couldn’t help but picture an actual Saola experiencing life as a refugee, which is what initially prompted the poem.

AL: When reading this collection I was reminded of a lecture by M. NourbeSe Philip titled “The Ga(s)p” which begins:

We all begin life in water

We all begin life because someone once breathed for us

Until we breathe for ourselves

Someone breathes for us

Very early on, in the third poem (“Relict”), we have an image of the speaker’s body post-partum: “incision under my belly / from where my baby emerged.” The scar to me highlights, not the action of birth but its imprint. The scar as the point of departure from categorizing the mother as baby and baby as mother, and of the impossibility of “otherness.”

As you put it so beautifully in “Origin”:

We have been made [into] each other and the baby

[is] made into the baby, quickening to a cadence we have

not yet learned, watery [language] of the womb.

This scar also anticipates the scar of the Saola’s belly when she dies in captivity and her fetus is cut, post-mortem, from her belly. The wound here is different, of course, in the sense that the baby is not made into the baby. One wound is enacted in the name of life, for movement, one for captivity inside a colonial imaginary.

As a reader, I was really intrigued by the delay between the appearances of these two bodies and their wounds. So, I’m first wondering if you’d want to speak to that and why these two bodies exist with 20 pages between them? Second, in one of the timeline or “node” poems of section three, you note “Some wounds / are themselves / the cure.” There’s a recognition in the poem, “Medicine,” that “resolution” or “cure” is often thought of as using one body to “restore” another body. The speaker then asks: “How to rupture / this reliance wide open, how to suture these wounds?” What is the relationship between connection and cure? Does language, for you, make the wound or suture it?

MDV: I didn’t realize the connection I had made between the two bodies, as you say, or even the wounds, until after reading through a first draft. I never fully know where a poem will go, let alone the entire collection. It’s a nice surprise when these unexpected connections develop of their own accord. I also hadn’t planned to write anything specific about my pregnancy, but it found its way into several poems. Whether it’s the speaker’s body or the pregnant Saola’s body, I think it’s also okay to let the bodies hold their own space and sense of autonomy in their own distinct areas of the collection without the need to create direct parallels for the reader. “Origin” as a long series also needed its own section and you’re right to observe that it comes much later in the book.

“Medicine,” which comes earlier, was my attempt to address the complicated history and industry around the poaching of mostly endangered animals for use in traditional medicine. There’s so much bound to that discourse, culturally, socially, and environmentally, and it’s a discussion that still has a long way to go. I think most people want to be cured, most want to heal, but it takes work and effort to do that on a genuine level. In some ways, to be cured is to be transformed and shift from one state of being to an improved state of being. That’s not easy to accomplish on one’s own. We also don’t give our bodies enough credit or care for the self-healing it undergoes on our behalf, like when we accidentally cut ourselves and a scab develops to protect the wound and regenerate the skin. We are capable of so much.

With regard to language, my sense is that it can both make the wound and suture it. Language can be a source of tremendous healing and restoration, but it can also inflict great violence and harm inside its capacity to injure, erase, remove, distort, and even kill. My sense also is that positionality and proximity to that language shapes the impact and outcome. It matters what language and who is speaking it.

AL: Are the headers for the section breaks meant to be Saola horns? I know they are meant to be almost parallel, and if so then these sections would suggest that the Saola is either looking away from the reader or at the reader. I love the dynamic of that, where they kind of both refuse their own nickname of the “Asian unicorn” where the optical illusion is rendered less important than the gaze and movement and animacy of the animal. Is it also connected to secrecy and agency? I mean secrecy in terms of the mysteriousness of the animal and also the erasurist US policies of hiding their war and its impacts on the Hmong people that your last book especially focuses on? In terms of agency, I mean this in the sense of reclaiming the gaze, from spectacle to livable?

MDV: The section break symbol was suggested by Rachel Holscher, the book’s designer, and I loved it when I saw it. It’s not exactly Saola horns as they tend to be more parallel, as you say, but the symbol certainly creates a horn effect. The symbol also resembles a twig or a branch which to me echoes the book’s cover. Even as I can’t confirm your instincts here, I don’t think it’s far-fetched to observe through the symbol, or through glimpses of Saola in the book, an animal that is looking away, or retreating from the outsider’s gaze to keep secret its own gaze. It suggests to me the possibility of a chosen obscurity or preferred seclusion. There’s a hiding that happens but on one’s terms given one’s agency to decide those terms. This feels very different from the perpetration of an imposed secrecy or inflicted erasure as has been the case historically for Hmong people due to the United States’ Secret War in Laos. To exploit a people by turning them into a proxy army, keep them secret from the world, abandon them at the end of the war, and walk away unscathed is a direct violation of those people’s right to exist, to know and be known, and to speak for themselves and attest to what they have been through. This history of the Secret War and its obscurity to most people is something I’ll always contend with in the intimate space of my writing and in the public sphere of my life as a Hmong.

AL: Given that you are a documentary poet who is really, to me, thinking of form as origin, I am really curious about your stance on whether or not you consider yourself a collage or an erasure poet? To me this speaks to a sensibility of composing based on either what is hidden or what is being reframed. And, has that sensibility changed across your three collections? For example, Yellow Rain to me is doing something really interesting with the watermark as origin, and that theme of water and birth doesn’t subside in Primordial, but asks to be approached differently by the audience and so the form of encounter is different.

MDV: It’s interesting to be considered a “documentary” poet. I didn’t set out initially to write documentary poems with Yellow Rain, but as I dug further into the subject and amassed a collection of declassified documents, and as I assessed how best to compose the poems into a whole book, the resulting work became “documentary” in nature and I suppose, too, in purpose. When I write, I try to prioritize what the work itself needs which then helps me determine the most appropriate form. To that end, I don’t know that I’d consider myself a collage or erasure poet, but my work has been in conversation with these approaches as mediums through which I have been able to bring myself closer to what I think I am trying to say. And you’re right, there’s something about these approaches that speak to a poet’s sensibilities around reframing, revealing, or concealing as a means to enact a reckoning of sorts. They challenge official narratives, introduce linguistic tension, and allow for contradictions to coexist such that what’s found on the page can feel just as heavy as what is missing.

AL: In “Deduction Remains,” the reader is given a clear, definitional, understanding of Saola. This poem really reminded me of Layli Long Soldier’s “38” in the best way—how it exposes the constraint of the historic, the definitional, the sentenced. This poem is preceded by a series of poems that lament the endangerment of the Saola, which I love because as a reader I’m being asked to think less about the animal as an object that receives the grief of the speaker, and more about the relationship between the speaker and their grief manifested by this word “Saola” that, definitionally speaking, I perhaps haven’t encountered. I will say that I had looked it up before, I think perhaps in reading one of your previous books. Still, the directive of embodiment meant I got to understand the animal via the speaker’s loss or via the bodily loss of homeland that this species represents in many poems. To me, the loss of homeland is not sentenced to metaphor, but becomes animate, walks around, witnesses what its absence does to its landscape.

In your table of contents you term the poems that operate from east to west as “nodes.” These poems are also interested in the disruption of the “sentence” in both its syntactic and carceral definitions. You also begin the collection with a Mei-mei Berssenbrugge line, which is, like many of her glorious lines, disjointed and refuting the sentence as the primary locus of meaning. How did you think about the sentence, carceral and non-carceral, as you were writing these opening poems that establish the Saola in the cosmos of this book? And maybe along those lines, can you talk a little bit about how you were or are thinking through embodying this loss of homeland without allowing it to be captured via metaphor and also, how you are thinking about syntactical directives and turns in your poems to reflect that lack of closure a historicized version of mass atrocity often prescribes via dates or timelines (which, I actually thought these node poems were recreating visually!)?

MDV: I’m a huge fan of Layli Long Soldier, and I particularly love her poem “38” for its sense of relentlessness with regard to the “sentence.” The sentence becomes a vessel for conveying information in a sequential manner, and she does it with such ease and poise that it unsettles in a good way by the time you reach the end of the poem. I certainly felt impacted by these ideas as I wrote “Deduction Remains.” The poem comes early-ish in the collection as a means by which to introduce the reader to Saola, but even prior to the poem, Saola is already there, its presence circling the speaker’s grief, as you note, and its name already evoked before the reader knows what it means.

I also considered the poem’s construction as a sequence or progression of ideas hinging on some degree of logic to spur the poem forward, hence the notion of “deduction.” Part of that construction includes maintaining a level of objectivity or impartiality in the speaker’s voice, which is a strange thing to do given that poems are often subject to emotion. But I think that’s where the basic sentence, simple as it may be, can still disturb, unnerve, or elicit an emotional response. We can be bothered or struck by the simplicity of sentences in a poem because we actually understand what it is saying, especially if those simple sentences build up to say something we might not have heard or felt before, like the word “Saola.” In this way, even a grammatically correct line or sentence can still destabilize the idea of the line or sentence as much as a poem that might be doing it outright, such as the node poems, which you astutely point out as an example.

Coming back to metaphor as a follow-up to one of my earlier responses, I think there will be an inclination to see Saola as a metaphor for war or the experience of exile, or an inclination to see Saola as a lens or window through which to see the war, or through which to convey the loss of homeland. It’s a fair assessment given that metaphor extends the potential of language to create new meaning, as Paul Ricoeur points out, and it allows for tension in what we see things to mean in relation to one another. But Saola is a living, breathing mammal with a right to exist as its own species free from my artistic need to have it serve as an “idea” or “concept” in my work. I have to respect that and focus more on how lucky I am to be alive and writing at a time when this animal also exists and hopefully is still living. We share a timeline and maybe that’s all I can hope for in my poems is a chance to honor that shared existence.

AL: In “Injury after Another” you write, “Necrosis of language, / neglect of tones and pitch.” From previous interviews, you’ve spoken about how the Hmong language was historically oral and without a writing system until a colonial project in the 1950s by missionaries imposed a writing system. These lines to me speak to how oral, indigenous languages are particularly good at adaptation, even if they are categorized by colonial powers as “dying” because they aren’t an official state’s language. In “Origin” you also write: “How war-torn to be voiced by a wound.” This made me think about Cathy Caruth’s meditation on Tasso’s epic “Gerusalemme Liberatta,” where the hero, Tancred, unknowingly kills his beloved, then cuts a tree that has trapped her soul and hears her voice cry out. The story, according to Caruth, “thus represents traumatic experience not only as the enigma of a human agent’s repeated and unknowing acts but also as the enigma of the otherness of a human voice that cries out from the wound, a voice that witnesses a truth that Tancred himself cannot fully know.” Can you speak a bit about your thoughts on sound, if it is the active form of language, what it activates that is distinct for you as opposed to written language, the use of anaphora in this collection, or anything you want to say about the aural wound of diaspora?

MDV: It’s interesting the connection you draw between these lines and Tasso’s epic poem. I grew up in a Hmong-speaking household so my earliest experiences with the sounds of language were rooted in the tonal shifts and monosyllabic cadences of the Hmong language. I didn’t realize until much later in my writing life how these sounds would impact and stay with me. I went through a period of obsessing over the monosyllable in my poems and, at the time, I didn’t make the connection that my obsession might have something to do with speaking Hmong. I think I was unconsciously looking for hints or sounds of Hmong in English through my attempt to translate, evoke, and re-interpret the musicality of words in my poems. I, like many others, have been forced and conditioned to live and write inside the monolith and institution that is the English language while leaving my first language, Hmong, to the ruins of afterthought. This tension has led me to unconsciously seek the Hmong language in all that I experience and hear in English, especially with regard to sound. Sound for me is an extension of memory. It’s a sensory-based container that can hold and recall the past, and because of that, it can haunt us. It’s the arrangement of syllables, echoes, stresses, and tones into new patterns that contribute to reshaping our various aural landscapes. For people who can access sound on a daily basis, we can often take for granted that we can hear. It isn’t until we hear something strange or unusual in a pattern of words that we begin to re-think the potential of sound in a poem. I take to sound, too, outside of written language, as a source of profound incantatory beauty and creation. The use of anaphora, repetition, or chanting for me activates the primal power of language to mesmerize and entrance, and this has the potential to change something in us while calling us toward a more proactive state of consciousness.

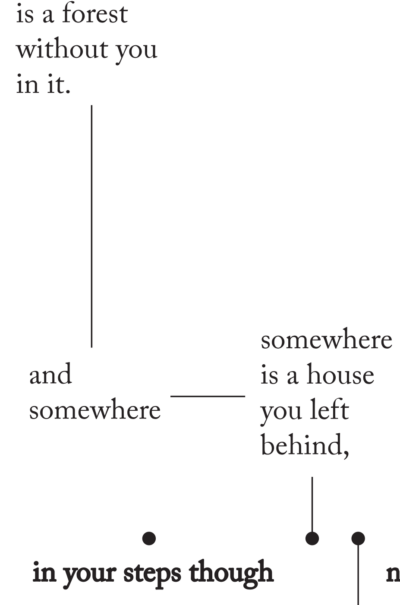

AL: In “Node: Make your stand” you write:

I was obsessed with this idea of somewhere being a location of you precisely because you aren’t there. That a forest grows where it would not have before. That the impact of your absence is equal to the impact of your presence. I’m wondering if it feels different to think of “homeland” as being dependent on the loss of it and what diasporic literature means to you?

MDV: For some refugees, and for my parents and some of the elders, I’ve observed that to think about one’s “homeland,” place of birth, or sense of shared geography with others comes also with the grief of thinking about the loss of it, whether one wants to or not. But contained within that are also recollections of what it was like to simply live there, to grow up there, to be on the land and experience the changing of the seasons as they arrived. My mom remembers leaving Laos, she remembers the loss of it, but she also speaks fondly of what it was like to live there as a young girl who farmed and tended to the livestock. It was a hard life, but she at least had all her family with her.

I think there’s a general recognition among some elders, my mom included, is that in theory they could return to Laos, but it will never be as they once remembered. It’s a kind of solastalgia and longing for the idyllic villages of their childhood. “Homeland” or the idea of “home” is no longer a physical location but a time from their past, a bygone era, a memory of what used to be, and a hard-hitting awareness of the world’s fleeting nature, all at risk of being lost at a moment’s notice. To get back home then is to get back to a remembrance of that time, which I think is part of what diasporic literature achieves. The reader joins in the act of remembrance while being reminded of the fleetingness of “here” and “elsewhere.” More importantly, there’s also the simple but profound assertion of having written to speak and testify to what has happened, to having existed somewhere and then be violently uprooted. I imagine that given the egregious state of the world we live in now, we may never see an end to this kind of literature, and I trust there will be more of it to come.