Interview // “On the Frequencies of Place”: A Conversation with Kinsale Drake

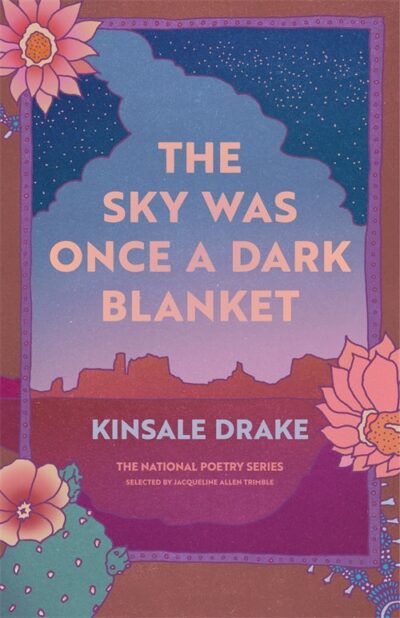

The Sky Was Once a Dark Blanket by Kinsale Drake was selected by Jacqueline Allen Trimble as a winner of the 2023 National Poetry Series. Published by the University of Georgia Press, this debut collection traverses the Southwest landscape, exploring intricate relationships between Native peoples and the natural world, land, pop culture, twentieth-century music, and multi-generational representations. Oscillating between musical influences, including the repercussions of ethnomusicology, and the present/past/future, the collection rewrites and re-rights what it means to be Indigenous, queer, and even formerly-emo in the twenty-first century. This interview was conducted via a Google Doc.

*

Coby-Dillon English (CDE): I want to start by congratulating you on this debut, The Sky Was Once a Dark Blanket. I was so excited when you were selected for the National Poetry Series in 2023, and I’m even more excited now that the book is here! I want to dive in and talk about the opening poem, “spangled,” particularly the opening words: “enough about you.” I wonder how you are thinking about this direct address. Why do we start here? Did you always know this is how the collection was going to begin? I’d also love to hear your thoughts on the route in this poem from its beginning (“enough about you”) to its ending line (“our song:”). How do you maneuver around the juxtaposition of “you” and “our” in this opening poem and across the collection in general?

Kinsale Drake (KD): Thank you so much for the congratulations! It’s been a really wonderful year so far touring for the book; I’m very grateful. I was listening to so many recordings and songs while working on the manuscript, and the opening poem was inspired by the sound and experience of listening to Jimi Hendrix’s “Star Spangled Banner.” I was really interested in how a poem can be an intervention—how it can startle a reader into paying attention. I think the “you” of this poem is perhaps the most overt address in the collection—really, it was a demand for redirection of attention at the level of sound and startlement but also more widely in terms of what narratives and songs are deemed canonical and acceptable. Likewise, the “you” can be a singular or plural address; “we” is collective.

CDE: Taking a step back, let’s talk about the collection as a whole. You’ve been writing and publishing poems for many years now. At what point did you know you had a collection or project? How did this collection begin to take shape?

KD: I revisited and reworked several poems that I’d written over the years, but truly it was through the demands of a college creative writing thesis that the manuscript began to take shape thematically and narratively. I had to write five new poems and edit five poems every two weeks to meet deadlines, and I’d just gone through some major changes in my personal life during my last semester, so it was a fairly intense period of writing and editing and rewriting and editing for several months. I finished the manuscript at a Vermont Studio Center residency in the winter following my graduation and then just started submitting it pretty much everywhere. My mentors and friends were incredibly helpful during this time in terms of feedback and talking through what the collection would look like. I pinned it up on the wall; I made watercolor paintings and moved things around and let the poems morph and condense and unravel. I’ve always loved music, how we inherit our tastes, and songs are so intricately connected to memory and landscape to me, so I knew there were a range of artists who would influence the poems sonically and lyrically. I had a professor who once told me that my poems were too “musical,” and that made me want to write about music even more.

CDE: To me, the best pieces of writing leave me with something to investigate further. After I read your collection, I spent the better part of a weekend listening to Mildred Bailey and reading about her life. Thank you for leading me there. I wanted to ask how she became an influence in your life and what it meant for you to write poems for her in this collection?

KD: I love that you asked about Mildred Bailey. I feel the same way about poetry as someone who knows absolutely too much lore about random people and things. My older sibling, Ronnie, had a huge influence on my musical taste as a kid; they’re eight years older than I am. They would pick up beat-up antiques and restore them for me, and some of them were record players or gramophones, even. There would be so much jazz and blues floating from their room—Billie Holiday, Ella Fitzgerald, Nina Simone—Mildred Bailey is very naturally part of that lineage, and you can tell in the clarity and tone of her voice, her linkage of her Indigenous identity to the Black diasporic experience in the early 20th century. She was interacting with and influencing so many jazz greats, including Louis Armstrong, often before they were incredibly famous. I just thought it was amazing how a woman from the Coeur D’Alene Reservation was able to have a career singing jazz in New York City during a time of such intense removal and erasure. It made me think deeply about the music she chose to write or cover; she recorded one of the earliest versions of “Georgia On My Mind,” which is so rich with longing and memory of place. That had a huge impact on the emotional frequency of the collection, where language and form is often mourning or reaching.

CDE: It’s a wonderfully sonorous collection that left me with a strong sense of place. In addition to Mildred Bailey, this collection references Jimi Hendrix, Hank Williams, George Strait, My Chemical Romance, and more. There is the “hum of yucca” and the “sound of under-water,” as well as birds, cicadas, dogs, winds, and a memorable snapping of a Juniper bough. I’m curious about how music, sound, and land are intersecting for you in this collection? What does it mean to you to translate a landscape onto a page like this?

KD: Music, whether in harmony with the natural world or emerging from our memories with loved ones, is intimately connected to storywork for me. There is so much to pull from in terms of genealogy—as Diné people, songs are sacred, and our stories bring us into the world. They teach us who we are, again and again. They are touchstones for us. Likewise, I was curious about historical understandings of “Native music” and the impact of ethnomusicology on what that music is now. What non-Native audiences may immediately think of is shaped by logics of containment and violence, from the very instruments of recording (wax cylinders, gramophones, sound archives) to what was considered to be important enough to be chosen for preservation. And yet, we’ve shaped our own canons of sound—ceremonial songs, seasonal songs, songs whispered in bunks or in the night, songs barely above a murmur. And, too, there are our choruses of joy—the joy of listening to a favorite song with loved ones while collapsing time driving together from one point to another; the chorus of the land and human experiences; the chorus of a desert, for example, which settlers often depict as merely empty space or a site of extraction.

CDE: I’m always curious about artist practices and rituals, how perhaps we tune ourselves to our worlds in order to create art. I wonder if you would be willing to share some of your rituals or practices. When you sit down to write, what is your ideal environment? Do you play music, wear a specific item of clothing or jewelry, write during specific times of the day, etc.?

KD: When I write, it’s often at night or in a rush because I’ve just read something remarkable and need to get my thoughts down immediately. Nighttime is peaceful for me; it feels more intimate and private. I’m also always wearing some kind of turquoise unless I’ve forgotten—that’s just a natural tendency—since my mom would always tell me to protect myself that way. It’s how we know the Holy People can see us at all times.

CDE: I’d love to also ask about poetic lineages. Writers like Joy Harjo, Sandra Cisneros, Tayi Tibble, Tommy Orange, and Layli Long Soldier are directly linked in this collection. Could you speak to how these writers influence you and your curiosity? Are there other influences, literary or otherwise, that helped you as you worked on this collection?

KD: I think poetry inherently honors the work of all those that came before us. I can hear their echoes and feel these writers around me as I work. It’s funny because Anglo poets have such a fixation on creating “original” poetry—that if it’s not doing something insanely “new” or “innovative” in their eyes then it’s just contributing to the “death” of the art form. I think if we continue to see poetry this way, it will almost guarantee its fading into irrelevance; though, this will never actually happen since so many Black and Indigenous writers and poets of color understand that creating poetry is an act of mapping, of tracing influence. It’s a beautiful thing to be part of a greater mosaic, to feel less alone. Pretty much every poem in my collection could have had an epigraph, and I prefer it that way, because I’m also trying to demonstrate to readers and to other emerging Native writers that there is so much more out there—that this is just a small window or portal into an entire beautiful literary ecosystem that’s been around, basically, since we began to tell stories.

CDE: I wanted to end by discussing another specific poem, “Theme for the nautical cowboy,” which won the 2023 Adroit Prize for Poetry. The image of the poem’s speaker and friend driving a truck across a “prehistoric ocean” has really stuck with me. This poem seems to me to be compacting past, present, and future into a singular moment, something that I think that resonates with the collection as a whole. The line “here’s to you, ancient and alive” has also been stuck in my head for days. Where did this poem come from for you? How do you see it operating within the larger collection?

KD: I love that poem so much. Thanks for bringing it up! It’s a lot of fun to read and part of that is because of its compression and expansiveness, the way it moves and breathes across time. When I was writing it, I didn’t want to limit myself in terms of sensory details or sounds or images or time-travel, so I broke the rules of narrative poetry that usually my professors preferred (ie., having a clear start and end point, moving in one direction in time, or flashing back to just one or two memories). Instead, I wanted the music and the humor and the dark and the heat and the cold and the fossils and the fish all shimmering and living and interacting. I wanted things to shapeshift and to show that the earth, the air, the sky, the rocks were all living, too. I made some sketches and watercolors of visual representations of that poem to push the images. My mentor Emily Skillings pulled my attention to blues in the poem—the “turquoise sliver of horizon, the creeping river invisible in the dark” is one of my favorite things I’ve written just sonically and in terms of what is moving all around us in a desert at night. It’s a poem of pleasure and joy, perhaps romance. It’s a scene of experiences that move me to write more poetry.