Interview // “On The Mess(iness) of Affinity”: A Conversation with stevie redwood

I met stevie redwood in the summer of 2019 when we were both in Ross Gay’s workshop at the Juniper Writing Institute. I remember one day Ross asked us to get in groups and gave us a few minutes to write and perform a short play. The play stevie and I put on (with another friend) was about taking down capitalism by pooping while on the clock at work. Though our play may not have successfully destroyed capitalism (at least not yet!), it did get more than a few laughs.

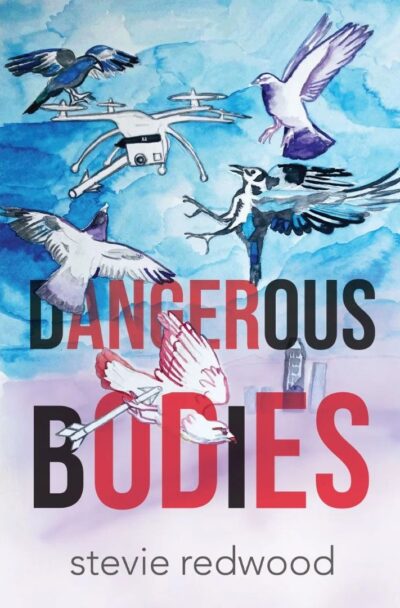

Bathroom humor aside, I found stevie and their work inspiring then just as I do now. Their poems—which ask us to question how we treat one another, to interrogate the systems that we have designed, and to resist injustice in our communities and beyond, are as urgent as poetry can be. When stevie’s first book, DANGEROUS BODIES / ANGER ODES, was published by Sundress Publications in June 2024, I couldn’t wait to get my hands on it. I jumped at the opportunity to chat, via email, with stevie about this wonderful book.

*

Josh Luckenbach (JL): The book’s cover says “DANGEROUS BODIES,” but nine of the letters from that title are printed in bright red (rather than black like the other letters) so that the red letters spell the words “ANGER ODES.” In this same way, each of the book’s six sections extracts one title out of another, so that, for instance, the section titled “Weather” becomes also “War.” What is the relationship between “Dangerous Bodies” and “Anger Odes”? Can you discuss your process of extracting words like this throughout?

stevie redwood (sr): I think there are so many ways to read and (con)figure and explore the relationships between dangerous bodies and anger odes: between danger and anger, between bodies and odes, between danger and ode and body and danger and body and anger and and and and…this is one of those things I’d maybe rather leave open to interpretation, so that whatever relationships other people find or make can just breathe and be as they are.

What I will say about the process of forming and naming sections of the book is that within each title and its embedded title—as well as within and between poems and titles in each section—I found myself looking to and for a tangle of intermittent resonance and suspended tension. That’s something I feel and think and write about a lot: the mess(iness) of affinity and imbrication and antagonism and contradiction and ways of trying to feel and think and act beyond a need for resolution or reconciliation.

I also wanted to bring in direct reference to elemental and material dimensions of life, to invoke these registers of living and dying that are the structures around us.

JL: There are other kinds of wordplay in your book as well, especially when it comes to density of sound. “Rupture Dentata,” for example, opens like this:

incisive windbite of autumn / a burst-ripe thirst for novelty / an

unfamiliar town & its handwave / of permission / a wet monsoon of

strangers / taut thrust / of bedrock against my ribs /

There’s so much going on sonically in this poem. Even in the first line, there’s the assonance of “incisive,” “bite,” and “ripe” as well as the “burst” / “thirst” rhyme (which is echoed later with “thrust”). I can’t help but read this poem out loud. How does sound factor into your drafting process? Do you ever feel yourself being led by sound? At what point does what the poem looks like on the page factor into your process?

sr: Thank you for the opportunity to think about this! I grew up a music kid—I sang somewhat seriously for a long time—and I think that that has forever structured my internal narrative(s), so naturally it also influences what and how I write. When I’m writing, and for that matter probably also mostly when I think, there’s an actual voice, with all its lyricism and percussion, in my head. For me, lyricism was always musical, and it’s stayed that way. In poems, I see that musicality mostly come out in formal ways: rhythm, pace, movement, how I punctuate and structure lines, the white space. It’s not something I do on purpose, but when I look at the book, there are a lot of lines that are sort of in rhythm with time signatures, often 4/4 or 6/8, and it makes sense—time signatures were one of the primary metrics of my early life! Generally, if I write a line and it’s not sonically satisfying to me, I will mess with it until it becomes so. I’m exacting in that way.

How I incorporate or arrange or choreograph sounds themselves, like sibilance or fricatives or vowel rhymes or whatever—I think maybe that’s influenced by neuroperversion things. There are textures to how words are held in (and expelled from) the mouth, you know? I like a meaty mouthful of sounds, like I prefer when there’s a lot going on and when the textures reinforce themselves and complement each other. If there’s not enough going on, I’m bored. Like, you will notice I am a wordy bitch. I would never compare myself to Mozart in any other way, but there’s this part in the movie Amadeus where he’s playing a composition for some fancy royal court and then at the end, someone frowns and goes “Too many notes!” It’s like that, maybe.

JL: One of my favorite poems in the collection, “Ode to the House of Weeping Queers: #1” begins “we trade notes about loving each other & killing capitalism.” In the poem, the housemates debate about whether or not they can still call themselves vegetarians if they eat rich people. The poem is a great example of something that I really admire about this book—that is, how it balances humor and anger and love. “Revenge Fantasy” is another poem that I think does this exceptionally well. Is that something that you set out to do in your work? I wonder if you could speak about that balance?

sr: I think maybe it’s almost the inverse of that—like perhaps instead of trying to make sure that humor and anger and love balance out in my writing, it’s that I turn to writing as an attempt to externalize or examine or confront or process parts of my own interiority that need some balance or levity. I have so much love and I have so much rage, and they feel hard to shoulder. Writing into and out of that can help move or shift or reconfigure it all in ways that feel less likely to break me, or at least less likely to break me today.

In the world as it is, I think love and rage are very deeply, inextricably entangled, at least for me. Love and rage, or even love and violence, are often at least implicitly discursively positioned as antagonistic to one another. Sometimes I internalize that positioning. But ultimately, though they can be hard to reconcile, or to synthesize, or to feel or hold or wield separately together, love and rage and violence and resistance and struggle in the context of global capitalist warfare are all thrashing around together on the same side of the fight.

The C.L.R. James epigraph in the beginning, The rich are only defeated when running for their lives—that’s not a metaphor. Frederick Douglass, Power concedes nothing without a demand. Et cetera. To be clear, I’m not trying to one-dimensionalize or cheapen or valorize the necessity of resistance, including armed or what gets called “violent” resistance, or its role in struggle. It’s just what’s necessary. And especially in a moment like this, when Palestine (and Lebanon, and Yemen, and Syria) have global attention in ways they haven’t before, it’s important for “us,” especially in the imperial core so physically far removed from the genocide and resistance happening there, to recognize and get behind that.

JL: In a similar vein, what is the relationship between love and activism/revolution/justice/whatever-you-want-to-call it? I’m thinking again about of that line “loving each other & killing capitalism.”

sr: Honestly, that is something I am perpetually grappling with. I think the question demands some curiosity about what love is, what it means, what it isn’t; what forms of love exist and how those different forms get taken up or left behind or leveraged in different ways.

On one hand, I know love is essential to making revolution, or even make strides toward revolutionary movement. I’m lucky to know and be learning with people who love and throw down equally, for whom those practices are not discrete. And there is so much love in the work that many of us are doing. Direct aid and (re)distribution networks, info sharing, zinemaking, meal trains, court support, de-arrests, political education and study groups, alleged destruction and redecoration of private and corporate “property” and general sabotage. That feels really palpable and beautiful, and it keeps a lot of us going.

On the other hand, there is liberalism and its cynical, opportunist instrumentalization of a very apolitical sort of “love”; the modes and expressions that resonate at frequencies of, say, recuperative, UN-model, human rights-based, reformist, sometimes pseudo-religious can’t-we-all-just-get-along type shit. Which, let’s be honest, at a structural level isn’t actually based in any flavor of love whatsoever; it’s just rhetoricized and branded that way. At a micro level—I mean, I’m a mammal. I understand a desire for love to be simple, easy, contextless. But it isn’t. I’m not saying don’t love who you love; I’m saying turning that contextless version of love into a pretext for a “politics” fashions it a handy weapon in a reactionary arsenal.

And then at the same time—this might make some people mad—there’s also a reality, at least in milieus I’ve been in, of radicals or “leftists” or whatever—anti-capitalists who are trying to help force or bring about a different end of the world—dealing with that liberal weaponization of “love” by equating love with liberalism; by keeping a distance from a lot of different kinds of much more honest, practicable love. And what we do need to do is figure out how to build and maintain relationships with one another that will not catastrophically implode or explode (and take a lot of collective energy, resource, and momentum with it) under the pressure of a hairpin because guess what, the state and fascists and the forces of repression are not a hairpin. TLDR: people don’t know how to treat each other or handle our shit and it’s getting in the way. Ask me how I know!

JL: Speaking of organizing against “forces of repression,” one of the tensions in this book is about the relationship between art and political action. What is the sociopolitical role of art? What is the artist’s responsibility in terms of their relationship to politics, justice? Where do you see poetry fitting into activism? Does it?

sr: I think I’m probably less likely to make grand statements about the kinds of poetry people “need” to write or the kinds of art people “should” be making than I am to look for a baseline of reflection and honesty from people about what they’re making and where it comes from. There’s in a line in “Revolutionary Letter #1312” (from the book) about what art cannot do, and what I would love is for people to be asking themselves questions about that—about what happens, and what can only happen, beyond and outside of art.

In terms of what art can do in a political sense, I will make a very small offering and say that I think art—making it, considering it, absorbing it—can be a really powerful buoy for people, and in that way I think it can help us reproduce ourselves as more resourced or more thoughtful people for whatever struggles we’re involved in. More importantly, I would also point everyone toward Fargo Nissim Tbakhi’s brilliant piece “Notes on Craft: Writing in the Hour of Genocide,” published last December by Protean Mag. Read that!

JL: In the poem “Hunger Strike” you critique landlords who protested rent moratoriums during the pandemic. When landlords in the poem call the rent moratorium “draconian,” you point out the irony, given that the term “draconian” comes from Draco, “the Greek legislator known for consolidating power / in the hands of landowners.” Your poem suggests that these landlords have lost the meaning of the word “draconian”; they use the word much in the way that we use dead metaphors in conversation without thinking about what they actually mean. Capitalism too is something many of us take for granted. We might even take landlords (perhaps the epitome of capitalism) for granted, as if it were a given that landlords or capitalism should exist. Is it fair to say that part of the poet’s job is to not take language for granted? To not take the existing systems for granted?

sr: I deeply appreciate the question and everything it’s fleshing out. If I’m honest, I think not taking existing hegemonic systems for granted is kind of everyone’s job! The poem in the book called “YOU WALK YR NEW BOOTS HOME FROM PAYLESS” is largely about this. (For instance: “be careful / what you learn to live with pain rent checks presidents.”) And yes, I do think it’s a poet’s job, a writer’s job, an artist’s job, to name what often goes unnamed; to render the familiar absurd.

As George Jackson has said and others have repeated, fascism is already here. One of the things reforms do is break off little pieces of these systems that a lot of us know are not working for us (or for lots of people) and repackage them, redesign them, and sell them back to us as something else that typically involves even more repression and extraction and surveillance. So the process of unseeing and re-seeing is an ongoing practice, or maybe more accurately, it’s a fluency we have to acquire. And we have to be vigilant about it.

JL: I remember an old version of your writer’s bio that mentioned something about how you enjoyed “trolling YIMBYs.” There is some trolling—of landlords, of the rich, of neoliberals, etc.—that happens in this book. Do you ever consider yourself a satirical poet? Are there other poets who have influenced you in that regard?

sr: Wait this is hilarious. I’m thrilled that you remember that.

I admit I just had to DuckDuckGo “satirical poets” so no, I have never considered myself a satirical poet as such. I consider myself a hater, basically. A hater with a lot of love. My friend Scout (Faller), a brilliant poet who ran a poetry reading series in Frisco called “No Worries if Not” before they skipped town for their MFA program, themed their final installment of the series “HATERS” and invited me to be one of its readers, which felt like a real moment of being seen and understood.

JL: The poems in this book often offer critiques of capitalism, liberalism, militarism, wealth inequality, climate policy, “the dominance of property,” and the “heteropatriarchal settler colonial relations” to name just a few things. Where do you find hope, today, to live as if the end “were not inevitable” as you write in one poem?

sr: I do think on a macro scale, I find fuel in looking to defiant living—to determined acts of life, including and especially illicit life—like what resistance movements are doing in Palestine and Yemen and Lebanon; like what Palestine Action is doing in the UK, what the Merrimack 4 allegedly did. What Aaron Bushnell did, and so profoundly carefully—that was an act of death against deathmaking and in the interest of life. I look for echoes of these things everywhere and in every dimension. I also have deeply caring and brilliant people in my life, and talking and learning and doing shit and being with them helps.

And I try—I often fail, but not always—to attend as closely to gestures and articulations of care and possibility and creativity and beautiful refusal as I do to the things that make life feel impossible. Because the hard shit is gonna happen and it’s really fucking loud. So if I wanna hear or see or feel things that aren’t that, I have to listen; I have to look. And those things are literally everywhere. Like, adults living in tents in Gaza are setting up games and obstacle courses for their communities’ kids, who are playing with cats they rescued from ruins. None of that should have to be happening, and yet.

People are organizing book fairs and free schools and doing direct aid. Waffle House workers in the southern US are unionizing to demand better working conditions and higher wages. In a town near you, people in jails and prisons are organizing work strikes in spite and refusal. In a bird-filled backyard near me, there’s a tenants’ union or a legal support crew or a needle exchange collective holding a COVID-safer meeting. Someone is catapulting over the subway turnstile while other people smile or turn the other way. People are cooking dinner for their friends and doing their neighbors’ childcare and emptying their loved ones’ top surgery drains. Someone is covering a shift for a coworker who needs to go to the doctor or the MTA office or, god forbid, the DMV. People are holding each other while they cry, and blowing raspberries on each other’s stomachs for a moment of laughter after a long fucking work day. People are helping each other get on SSDI and making each other mixtapes and just, like, remembering their loved ones’ birthdays. There are sunrises and sunsets and mountains and peaches and ducklings and trees. You know? It’s everywhere.

JL: What projects are you working on now?

sr: In terms of writing projects, I recently published a chapbook called INTIFADA through RM Haines’s fantastic Dead Mall Press. The chapbook is a fundraiser for a few different things, including a network of Gaza mutual aid projects and a local-to-me Palestinian woman supporting her family both still living in and forcibly displaced out of Gaza. We were originally also sending funds to Samidoun, before the US and Canada collaborated to classify it as a “terrorist” organization, and I hope to be able to send funds to them again.

Beyond that, I think what I’m working on now perhaps takes place outside of poetry, though of course my life influences my writing, so there’s some blurriness there. As my reality around chronic illness and disability continues to change, I think my current project involves continually negotiating and redetermining my relationship to both my individual life under capitalism and to the collective political struggle for life without capitalism. Being chronically ill eats up a perpetually shocking profusion of time and energy. Trying to figure out what it looks / feels / is like to be chronically ill and still do life and survival and sociality and commitment and struggle and just being a person in the world—all that eats up ever more. It’s a full-time job that doesn’t pay. But for the moment, I’m housed, I have enough food, I have loved ones. That’s huge. It’s everything. As for writing—it’ll happen again, eventually, probably. I think.