Interview // “On the Transformations of Fire”: A Conversation with H. G. Dierdorff

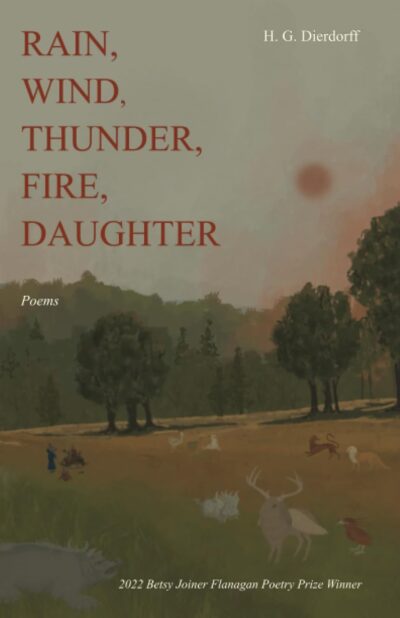

H. G. Dierdorff’s poetry collection, Rain, Wind, Thunder, Fire, Daughter (University of Nevada Press 2024), explores the body, sexuality, ecology, and deconstructionism through the generative powers of language. Readers are invited to follow the speaker’s pursuit of a new cosmology—one capacious enough to hold the complexities of identity—set against the backdrop of the West Coast wildfires which flicker throughout the collection in a recurring lyric essay. H.G. and I went to the University of Virginia’s MFA program together, and two years after we graduated I had the privilege of interviewing them over Zoom.

*

Jeddie Sophronius (JS): Many of your poems engage with the complexities of language. Some of your poem titles juxtapose closely related homonyms, separated or “divided” by a line. You have also likened language to a fungal network within a forest in your “Notes” section. Can you talk more about your meditation on language in the book?

H. G. Dierdorff (HGD): Language, and self-awareness about the use of language, is a reoccurring theme in the book. It reflects the kind of ecopoetic consciousness that I was learning while I wrote this book, which emphasizes a self-conscious use of language in which we’re questioning how we, as humans, use language to represent the more-than-human world. Simultaneously, the book is about religious belief and deconversion. I was thinking through how language, especially the language of my childhood, created belief for me, and how I use my language to imagine and believe what’s possible. So I tried to make language, as much as possible, enact more than one thing. And that’s important to me, because growing up, the school systems and religious institutions taught me only one use of language, where language is this static, logical, factual tool to prove the truth. Or, if you used language figuratively, you were ideally using metaphor or allegory to point to some Christian story or symbol. So, playfulness and experimentation were crucial for me in writing this book and allowing me to access the expansiveness of language.

As I was writing, I came to view language as a network of relation, largely inspired by Mikhail Bakhtin and Édouard Glissant. A word is never a single, static entity; it’s not simply the “signifier” corresponding to a “signified” object or meaning. It’s many, many things, and it’s constantly shifting. It’s always passed between people, always contingent upon its context, always enmeshed in a history. These linkages and pathways where language gets transferred and transformed form a vast, largely invisible web that feeds how we think and communicate. My consciousness and speech are shaped by the people I’m in relationship to, as I consciously or unconsciously borrow their words and absorb them into my own identity. I use the metaphor of a fungal network to visualize this interconnectedness, and also as a way to imagine how my human language might be similar to the language of trees.

JS: The reason I started with that question is that your answer, I knew, was going to open up the rest of my questions. In “Mapping the Channeled Scablands,” you describe learning about evolution from across the canyon, showing a distance between the speaker and non-Christian narratives. Similarly, in “A Classical Christian Academy,” the speaker observed the ridicule of another non-Christian narrative in a school setting. Can you say more about your exploration of the tension between religious orthodoxy and the rest of the world?

HGD: The dominant binary I was taught was “Christians versus unbelievers,” where Christian orthodoxy only included the very small sect that I grew up within. Any kind of other knowledge or language was automatically perceived as being against. And that defensiveness, that “Us vs Them” logic, is behind a lot of ideological violence that often manifests itself in physical violence. A lot of the work I was doing—writing this book—was becoming self-aware about the defensiveness I had been taught around certain conversations or topics. I began to question that and question where it came from. I found, ultimately, that the core of that impulse came from a fear of not belonging to my family. A fear of not being loved. Behind that, of course, was the fear of not being good and of being eternally punished by God. Fear is the primary impulse behind every violent logic. When I realized this, I began trying to unlearn my defensiveness and educate myself about topics like evolution and sexuality, not from a place of fear, but from a place of love and curiosity. Writing this book was my attempt to do that.

JS: In the titular poem, “Rain, Wind Thunder Fire, Daughter,” the speaker’s father describes sin as departing from the shelter of God, echoing a broader theme of departure. How does this departure manifest in the speaker’s journey of self-discovery and liberation?

HGD: I framed the book as this coming-of-age story; there are many ways in which it does not fit that, but I think placing it in that category makes it readable and understandable to many audiences. That’s important to me. The dollhouse in the titular poem became a prominent image for this story. When I think about what it meant for me to leave Christianity, it meant, according to the myth I was taught, that I had to leave this place of safety, depart from the house, and venture out into the storm, into danger, into the place of madness and foolishness, which is also reflected in the reference to King Lear in that sonnet. Of course, the poem simultaneously undercuts this narrative; the house is a cut-open dollhouse, which doesn’t make it very reassuring as a symbol for divine shelter. Throughout the manuscript, we see the speaker move across physical distance as she moves even further from her Christian upbringing. We move to Virginia in the poem “Exodus,” and that departure has religious symbolism, echoing a bit ironically, since the “promised land” the speaker travels to is one fraught with the violence of colonization, United States militarism, and ecological destruction. This departure begins the inherent tension throughout the manuscript between the speaker’s longing to be back in the land that she considers to be home and her grief in realizing the complicity of her own actions in the climate crisis. The speaker struggles to understand what that means and starts to understand who she is outside of these contexts, out of the context of family, inherited Christianity, and the landscape of the Pacific Northwest.

JS: I’m glad you brought up the sonnet because your poems intricately explore the theme of loss, be it of a body, ecology, home, or relationships. Yet recovery is subtly woven throughout your work, and notably, your manuscript features many sonnets, a form historically linked with love. How do you reconcile the themes of loss with the sonnet’s association with love?

HGD: I was taking a sonnet class when I started writing the sonnets, and that was very generative for me because it helped me to understand how the sonnet, as a form, is a part of this long conversation. A lot of the sonnet is about love and romance, but it’s also a lot about death. The sonnet’s small form, consisting of 14 lines, also links love and death in its brevity. When I was writing, I was constantly forced to leave out so much, so there was an echo of loss around the page, which I tried to magnify by placing the sonnets in the center of the page. Throughout the book, the speaker learns that love—especially love for the human, animal, material, and natural world— is necessarily linked to loss. This sounds so obvious, now, but after believing for my entire life in heaven, it was pretty terrifying and also strangely beautiful to realize that death actually exists, that one day I am going to cease to exist. Finding spirituality and meaning in this material world—instead of always looking forward to an eternal, perfected afterlife—means embracing death. Death, from an ecological perspective, is a necessary part of life. In the forest, when organisms die, they’re giving life to future seedlings. Many kinds of environmental destruction are harmful precisely because they prevent this transfer of nutrients and atoms, which is where anger comes in. I think anger is a really big part of the sonnets as well, and anger is a kind of productive energy between grief and love. To be able to move from grief to love, we need to fully acknowledge what we have lost, and the kind of love that fails to recognize loss is no longer interesting to me. It’s stagnant.

JS: Can you say more about the creation process for the “As the West Coast Burns” sequence, and how you navigated its stylistic and thematic elements?

HGD: “As the West Coast Burns” was written later than the sonnets, and it was written as I was crafting the shape of the manuscript, so some of the sections were written to shape the manuscript into these parts. I began writing the lyric essay because I found that I needed more space to weave everything together. After all, the sonnet is great, but I was leaving a lot out. This book is holding onto so many threads, and I needed a space to be a little more expository, for the reader’s sake and my own, as I was working through all these big questions and griefs. As for the experimentation with punctuation that occurs throughout, I found a lot of inspiration from Brenda Hillman’s use of the lowercase “i” to signify ecological consciousness and equality with other beings rather than asserting anthropocentric dominance. Her use of punctuation in books like Extra Hidden Life, Among the Days where she’s using punctuation to have a conversation with lichen also inspired me. The lyric essay also incorporates documentary poetics, weaving together news articles, scientific research, and the speaker’s own dreams and memory.

JS: In a way, they were giving context to the sonnets, would you say?

HGD: Yes. Musically, too, I’m always thinking about the music. Because the sonnets are very intense, they’re often very pointed and fast in their direction. They’re moving quite quickly, even between sonnets, since the last line of each sonnet contains a word that is echoed in the first line of the next poem, pulling you forward. This mimics a sonnet crown, without fully realizing it. The lyric essays feel like a space to breathe and rest from this hurtling speed, and this pattern is how I experience grief a lot of times. These periods of really forward-moving, action-motivated anger interspersed with wide, almost stagnant, times of sorrow. These spaces feel like swales, where the curve of the earth pulls everything together, these holding spaces where every grief touches another, and it can feel impossible to move through or out of them. From the feedback I’ve heard from readers, the essays do feel a lot more emotionally vulnerable, perhaps also because—unlike many of the poems in the book—I was living through these events as I was writing them.

JS: Going back to the topic of Christianity, you describe leaving Christianity as a long, slow, and tangling that seems tied to the notions of home relationships and the abandonment of familiar narratives. The book also engages extensively in world-building: mapping the land and the damage done to the land. How does untangling from Christianity inform your approach to world-building in your poetry?

HGD: When I decided that I no longer wanted to be a Christian, that it no longer fit with who I wanted to be in the world, and how I wanted to live my life, I had to very intentionally remove that language from my mind. It was so dominant. My entire world was that Biblical language. So I began a conscious process of untangling, picking apart, and choosing what I wanted to keep and what I still believed to be beneficial, as well as what I wanted to set aside for a while and see if I came back to. I decided to stop using the word “god” for a while, just to observe how I was using it, and to see what other words I could use to describe those experiences or feelings instead. As a poet, I felt this extreme dearth of language. I didn’t know how to speak anymore; I didn’t know how to think; I didn’t know how to write—because I couldn’t trust my own use of words. I turned to the language of ecology and natural history to fill this loss, and so the research I was doing about wildfires and about the history of the land in the West was part of that real, practical rebuilding I was doing.

Before, I couldn’t see a tree just as a tree. It was always: “What is this tree saying about God? What is God saying to me?” I was more concerned with my own spiritual truth than the material existence of another being—this same kind of logic was used to defend manifest destiny and many other violences in the history of this country, including our ongoing refusal to do anything about climate change. Finally, through this new language, I realized, “Oh, a tree can just be a tree. How can I look closer at the tree? How can I experience wonder and adoration without having to view it as a symbol of something else?” And my entire perspective just completely changed. The way I experience other people and myself completely changed.

JS: Growing up, as a Christian, I found silence about our bodies with anything flesh-related, seen as sinful. Your work reclaims the body and its parts, often abandoning certain narratives. For example, fearing eternal damnation is contrasted with the idea that the world is already burning, yet there’s also reclaiming of the body as seen in “Double Sonnet with My Shirt Off.” How do you decide which inherited narratives to abandon, and which to reclaim?

HGD: Embodiment might be the most difficult and also powerful practice I’ve done to unlearn that Christian idea of the wickedness of the flesh. The more I am aware of my body, the more I’m able to listen to it, the more I am able to care for myself and others. It’s always pulling me toward connection and pleasure and joy, leading me further into my senses, asking me to fully experience all that is good, right here in front of me. I think, in my book, reclaiming her body gives the speaker the freedom and courage to actually name what’s going on. All the shit that’s going on in the world with climate disasters, and the silencing of women, and the violence against indigenous peoples—I don’t think that these poems would exist unless, simultaneously, I was experiencing love, kinship, and pleasure in my life.

JS: I can’t help but think about the prevalence of the four classical elements in your book, particularly fire. Fire holds such a strong symbolism: hell, transformation, wildfire. You also quoted James 3: 6, framing fire as a metaphor for the destructive power of language and the profound impact of words on one’s life trajectory. Can you share more about the symbolism of fire in the book?

HGD: That was a very generative thread for me. This book began out of—sorry someone’s fire alarm is going off, ironically. Maybe there is a god [laughs]. This whole book began as a project in my ecopoetry class in grad school, where I decided I was going to research wildfires in the Pacific Northwest, and their relationship to land management and climate change. I didn’t expect the project to turn towards my family and become so personal, but then fire just became this through-line that I followed. I became interested in the difference between fire as a material substance and fire as a cultural symbol. I was amazed at the disparity between the actual function of fire in ponderosa ecosystems—where it’s a necessary cleansing that helps promote the biodiversity and life of the forest—and the narratives about fire in Western literature. Especially, in the United States, fear of fire feels inextricable from the Biblical symbolism surrounding it. The fire and brimstone sermons that were so influential in the First and Second Great Awakenings gave birth to American evangelicalism, as well as much of the political and spiritual consciousness of this country. These interpretations of fire as divine judgment and damnation then become the lens through which white settlers viewed the natural phenomenon of fire in the West. And then that, in turn, influenced the history of land management and fire suppression, which has led to this huge deficit of fire, which is directly causing more severe fires right now. I was interested in how to write this interaction between “nature” and “culture,” as well as how to break down that binary itself. I wanted to, as much as possible, diversify how fire is portrayed and push against any one dominant narrative or symbol.

JS: Hannah, thank you so much for your time. I have just one last question for you. If you could create a Paradise for your speaker, what would that Paradise look like?

HGD: First of all, I don’t believe in Paradise. Not religiously, nor environmentally as an idealized point in the past when the earth was free from human impact. And for the speaker in my book, it’s actually really important that she ceases to desire Paradise as a promised future escape from and resolution to pain. What I think my speaker really needs and wants—for herself and others—is honesty. Honesty and vulnerability. To be heard and believed. To be held with tenderness. If there is an area or space possible that could do that kind of healing work, it would probably look like sitting on the ground underneath a large tree somewhere. It would look like silence, and it would look like sharing grief, anger, and love without resentment or bitterness. This is going to sound stupid and cheesy, but this is our Paradise. I’m back in Oregon right now, and it’s incredibly beautiful. It’s June in Portland. If you haven’t experienced it, it’s 60-something degrees outside, maybe 70, sunny. There’s this amazing light through the trees. We have received so much, and, yes, every moment it is ending. If we are not here fully, what else are we going to do? What else are we going to do with our lives, but be honest and fully open to receiving? That’s what I want.