Interview// “The Unfamiliar as Poetic Landscape”: A Conversation with Ally Ang

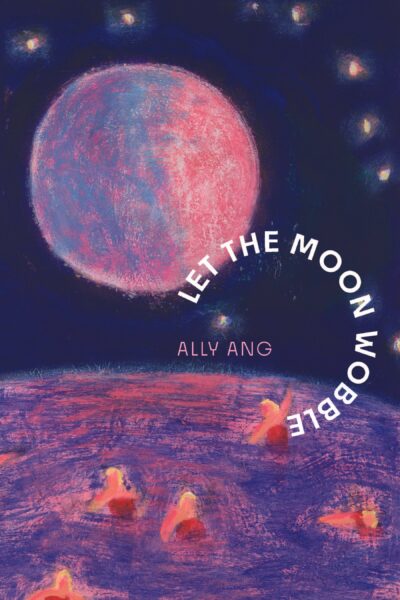

In the Spring of 2024, I read with Ally Ang at Open Books Poetry Emporium in Seattle, Washington. We knew each other through our mutual connection to Game Over Books (them in editorial, me an author), a press characterized by its indulgence of nerdy or whimsical project books; I found kinship with my pressmates in coming up in slam, or making poetry from places one would not expect. My connection to Ally, too, feels rooted in this: their debut, Let the Moon Wobble (Alice James, 2025), makes poetry from places one would not expect, imbuing each poem with warmth, with whimsy. We enjoyed an outdoor meal in the pleasant Seattle fog before our reading. Full of anxious energy and grateful to get some of it out through our budding friendship, I told them I had a yeast infection and thus was in a gross and weird mood. And so, to honor my gross and weird mood, they read “Pap Smear,” during their set, a poem that plays with the eerie intimacy of gynecological care: “The doctor makes me laugh while her hand / is inside me and it’s just like love, except she is also / scraping cells from my cervical canal.” I liked that we both had sort-of-crass poems to present the audience, a push of intimacy with everyone in the room that simultaneously felt like an inside joke. This careful music is resonant throughout Let the Moon Wobble. Ang’s line carries charm towards something cutting. As quickly as we fall into the romance of a moment we are brought back into reality, and so each realm blends and informs the other. There is no reality without romance, there is no romance without grief. And so this is life Ally renders for us: a life where one pays attention, a life that requires giving in fully to feeling. In our conversation over e-mail, Ally tells me they don’t really have an imagined reader outside of their friends—and Let the Moon Wobble feels like the most wonderful friend, then: one who is both gentle and firm, one who knows how to have fun through grief and when to let the grief be loud.

*

Summer Farah (SF): I wanted to start with the poem that gives the book its title, “Invocation”: “Let the moon wobble. / Let the basil plant flower. / Let the poets discombobulate.” I love the blend of registers, the hopeful and natural and strange, such a fitting beginning for the poems to follow. Tell me, what does it mean to “let the moon wobble”?

Ally Ang (AA): The term “moon wobble” refers to the fluctuations in the moon’s orbit around the Earth. Due to the elliptical nature of its orbit, throughout the second half of the 18.6-year lunar cycle, the moon’s gravitational pull causes the ocean’s high tides to become higher and the low tides to become lower. While the moon wobble is a natural phenomenon, when combined with the rising sea levels due to climate change, it will lead to increased coastal flooding over time.

I was drawn to this term because 1) “wobble” is a delightful word that I don’t get enough opportunities to say in my daily life, and 2) it’s a reminder that nature is not orderly or static, and since humans are part of nature, neither are we. It also evokes the tension between the natural world and capitalism that is present throughout the book.

To me, to let the moon wobble means to embrace the messy, queer, changing, ungovernable parts of ourselves that are reflected in nature.

SF: I’m thinking about the different spaces that make up this book: the bus, a gynecologist office, the dentist, and so on. I like the distinct feelings you pull from each—I feel so very rooted—whether it’s moving through a traumatic moment with the speaker or something pretty funny. I’m interested in the ways different spaces inspire you, whether they be physical or digital.

AA: For some reason this question stumped me for a while! I actually took the train to the end of the line and back solely because I thought it’d be easier for me to answer while in motion and I was right.

I don’t feel very present in the physical world. I feel like I experience life primarily with my mind and my body is just along for the ride. If I could abandon my body and exist as disembodied consciousness, I would. But I know that’s not a great way to go through life or to be a poet: the poems that emerge solely from my intellect with no tethering to the physical or sensual are frankly boring.

Poems are where I challenge myself to be more present in my life and my body, to actually pay attention to how I am moving through the world and to what’s happening around me instead of being completely absorbed in my own thoughts. While I get most of my writing (in terms of putting words on a page) done while I’m glued to a desk, the observing/experiencing part of poem-making asks me to be out in the world. I don’t have a car so I spend a lot of my time on buses, on trains, walking. I’m an extremely nosy person and I’m always watching and eavesdropping on people. I love how the act of paying attention defamiliarizes spaces that I’ve been to many times before and makes them feel new and exciting. I love how poetry inspires me to romanticize and trouble the mundane parts of life; it makes the experience of having a body and being a person almost bearable.

SF: Wow, I really love how you describe the act of paying attention as “defamiliarizing” a space; I similarly do not have a car and spend a lot of time on the bus, train, or walking to my destinations. I’m pretty absent-minded and addicted to my phone, which I think halts my ability to become familiar with my surroundings. I like this shift that re-frames attention as opening us up to something new. You say you do your writing at a desk, but do you write things down as you see them, then file them away purposefully for a poem? Or does it feel like something that comes more organically when you’re sitting down to write?

AA: I do file away little fragments or lines or images in my notes app or a notebook if they occur to me while I’m out and about, but actually constructing a poem requires my full attention. However, now that I say that, I realize that a good number of my poems were written when I was supposed to be doing something else—by which I mean work meetings. So I guess poems require my full attention unless my full attention is supposed to be doing work for my job.

SF: I wanted to shift gears a little bit; in the poem “Quars Poetic” you write:

Because last night I dreamed I ran

into a friend in the aisles

of a used bookstore, touched

his arm as though neither of us

could die.

You are one of the poets I feel comfortable talking about ongoing-pandemic realities with, which is unfortunately a small pool. This book engages with the pandemic and escalations of fascism that precede and continue it; what was your timeline of writing? I’m wondering especially at the possibility of that freaky feeling of when a poem might feel more relevant with each passing year.

AA: While the earliest poem in the book was written in 2018 and the most recent was written in 2024, the very first, nearly unrecognizable version of this book was my MFA thesis, which I wrote while I was in my MFA program from 2019-2021. At that time, it truly felt like the world was ending: this deadly virus that we barely understood was running rampant, there were massive uprisings against anti-Black violence and police brutality in my city and across the nation, and I was quarantined by myself in a city where I hardly knew anyone, trying to workshop poems on Zoom. Spending the apocalypse in poetry school felt so absurd, and I was grappling with that absurdity in the poems that I was writing and turning in for workshop.

When I first thought about publishing this collection, I worried that people wouldn’t want to read a bunch of pandemic poems, that they would situate the book too firmly in the time period in which it was written. Honestly, I wish the pandemic poems were outdated, but they still feel depressingly relevant, at least to me. I don’t talk about it publicly very often because I get the sense that people don’t want to hear it, but I still feel a lot of grief, anger, and fear around the pandemic, how it is and was handled by our government, and how most people refuse to acknowledge it. At this point, almost six years since the start of the pandemic, most people don’t want to accept that it is still ongoing and that Covid is still killing and disabling people.

SF: I wish the pandemic poems didn’t feel relevant! It is as you said: so many are participating in a denial that continues harm. I do believe there is potential in art-making against this harm, whether it is a forcing of attention to reality in the work itself, or curating spaces that do not let people pretend otherwise. I’m really excited by your reading series, “Other People’s Poems,” which I observe on Instagram with immense longing! I know that your host space, Open Books Poetry Emporium, is masks-required. I’m interested in this balance of absurdity as a method of processing, alongside tangible actions in the way you build community through art. Who are others you look to, artists or otherwise, for both of those cues?

AA: I love Open Books! They’re such a beautiful model of community care, not only by requiring masks at their events, but also by housing the Workshops 4 Gaza bookshop and helping to raise funds for The Sameer Project. It’s such a dream come true to be able to host Other People’s Poems there. I feel grateful that there are other groups and spaces in Seattle that also prioritize accessibility, including Left Bank Books, Pipsqueak Community Space, Kink Center, Trans Pride Seattle, Queer Trans Combat Arts Seattle, and many more. I’m also inspired by Covid realist artists like Ariana Brown, Kimya Dawson, Mimi Zima, KB Brookins, Lady Queen Paradise, and others who speak frankly about the ongoing pandemic and how it affects their careers and the way they make and share art. I go to plenty of events where I’m the only masked person or one of a handful of masked people, and I still enjoy those events, but when I go to events where masking is required or strongly encouraged it makes me feel so much more held by and connected to the community. It’s in those spaces that I am the most optimistic about our ability to care for each other through The Horrors™.

SF: Thank you for that—it does make the world feel less small, less awful, when you remember how many are trying to make it so.

I want to return to the text. There’s a lovely spread of unique forms in your collection: abecedarians, surveys, footnotes. I was particularly interested in the “Heartbreak Mad Libs,” especially alongside the different manifestations of grief operating in the book—including that specific section. Could you tell me about your approach to form, and the ways play operates in the book?

AA: When I was a baby poet many years ago, I rejected received form because I was like, “Poetry shouldn’t have RULES!” That was my youthful arrogance talking and it makes me cringe to think about now. It was only when I started reading more widely and rigorously that I realized how much possibility, freedom, and play there was within form. As I studied, I discovered poets who were doing new and innovative things with received forms (Taylor Byas, Terrance Hayes, Tiana Clark) and poets who were creating brand new forms (Jericho Brown, George Abraham, torrin a. greathouse, Kenji C. Liu).

As I wrote the first drafts of this book, I was in a phrase of trying new things and finding my poetic voice. Form gave me a container that proved to be very generative—it’s easier for me to set out to write a pantoum than it is to start with a blank page and just try to write a poem from scratch. Having that constraint allows me to get something on the page, even if the poem ultimately breaks out of that form in later revisions. So whenever I saw a poet doing something cool with form, I wanted to give it a try. The Mad Libs poem, for example, was written after I read “poem mad lib for the apocalypse,” published in Underblong by Angbeen Saleem. Many of these formal experiments did not make it into the book—I’ve written like three or four failed sestinas that will never see the light of day—but some of them did. Even though a lot of the poems in the book deal with very heavy subject matter, I wanted to maintain the spirit of play and experimentation that I felt as I was writing the book, and I think/hope that form is a way of making that present for the reader.

SF: Oh yeah, Taylor Byas does that really awesome form calendar for National Poetry Month, it’s such a great resource. When I spoke with Leila Chatti about her collection Wildness Before Something Sublime, she said something similar about form: “I needed play in this collection because the content was too difficult for me to face alone.” I like that you cite so many others in this consideration of form, that the act of it creates company when executing the poem. Do you feel like you resonate with Leila’s sentiment, or does the desire to play with a form come before the content?

AA: First of all, Wildness Before Something Sublime is my favorite book of 2025. Just putting that out there. But to answer your question, yes, that resonates! Sometimes a poem will start as purely a formal experiment—like, “Hey, what if I try to write a duplex?” without having any ideas for what the duplex will actually be about—but more often I have some idea that I’m circling around but don’t quite know how to articulate, and form helps to unlock it in some way. And as you and Leila said, form puts me in conversation with all the other poets who have written in that form. If I write a sonnet, I’m also thinking of Wanda Coleman, Shakespeare, Diane Seuss, Terrance Hayes, etc, etc. It’s a way of bringing my literary lineages closer, and that can make what is often a very solitary act (writing poems) feel more connected and connecting.

SF: Wildness Before Something Sublime is also in my top 5 books of 2025! I read it over and over and over as I was revising my own collection; it definitely encouraged a new sort of precision and play on the line level. Sometimes, it led me to overhaul the form of a poem entirely. What were some transformative moments for you in the process of making the book?

AA: It’s hard for me to identify particular moments because the book evolved so gradually over such a long period of time (I think the book went through somewhere between 10 and 100 revisions since its days as my MFA thesis), but one transformative process was what I called “the dysphoria edits.” When I first started writing these poems, I thought of myself and my identities—particularly gender—very differently than I do now, so it was a big challenge to revise the book in a way that would honor the spirit of the poems as I wrote them while also not making me want to peel my skin off while reading them.

It’s weird to publish a book that’s been so many years in the making because the poems are old to me but they will be new to most people who pick up the book. Many of the poems are not ones that I would write today, largely because I have a very different relationship with gender now, and while I did make big changes to some of them as I revised to make them feel a bit more congruent with the person I am now, I ultimately had to come to terms with the fact that the book represents a particular period of my life and it doesn’t have to represent everything I think, feel, and am in perpetuity, and that I cannot control what readers may extrapolate about me based on the book. Hopefully I will keep changing and writing books forever!