Interview// “Where was the love story?”: A Conversation with Jessica Laser

Jessica Laser’s third poetry collection, The Goner School (University of Iowa Press, 2024), performs the hilarities, heartbreaks, and attempts at healing of a generation. Academics and adolescents move toward the light and duck into the shadows, looking for stage left. From posh living rooms to diner breakfasts, these poems blur transcendence and the ordinary; ritual and habit. Laser dares, “you could dim us,” then careens, unblinking, into the sun.

*

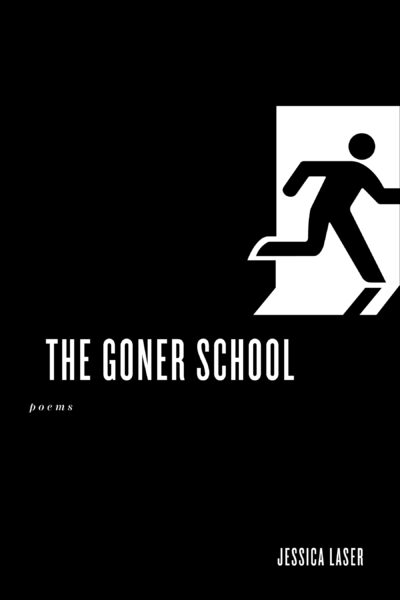

Kia McGinnis (KM): Let’s begin with the cover. I found the art for The Goner School striking (and surprising) in its monochromatic minimalism. What world or story does this imagery inspire in you?

Jessica Laser (JL): I wanted the cover to be an exit sign, but in the way that exits can also be entrances. When you leave one space, you enter a new one, like T.S. Eliot’s “In my end is my beginning.” So I imagine this figure running with a sense of urgency, but there being a certain amount of ambiguity about whether the figure is running out of a space or into one. I also hoped the cover might be funny enough to ground the book’s heavy title.

KM: I saw a metaphysical portal when I looked at it.

JL: Portal! That’s the perfect word.

KM: The Goner School covers such a breadth of topics that I’m curious about what you’re curious about now.

JL: After I finished the book, I knew I would have to put it down, and maybe even put poetry down, while I finished my PhD dissertation, which finally I did finish. I’m most excited now about being in a non-argumentative headspace around reading and writing. And I’m most curious now, as I always am when I return to poetry, about trying to understand what poetry is now, or needs now, and what poetry can and can’t do, which, of course, you can only figure out by having the courage to write the poetry. It takes a lot of comfort with uncertainty, with not knowing what you’re doing, a courage I must admit I can’t always access.

KM: Hearing you say that reminds me of one of the book’s motifs: sitting in the unknown.

JL: Sometimes I feel sick of defining poetry as a sort of language that touches the unknown, or the unknowable, or the unsayable, but in the end it has seemed to me that a life grasping at certainties is a lot more painful than a life that cultivates a loose grip; and poetry, with its loose grip on conventional modes of linguistic communication, is a good way to speak to that. It’s my poetry mind that snags happily on phrases that might resonate but don’t make perfect sense, or phrases that seem more resonant removed from their original contexts, like the title of the book, even, “The Goner School.” On a road trip from Portland to Berkeley in 2019, I passed what appeared to be an old, one-room schoolhouse with a sign on it: The Goner School. It just seemed funny, like a place we’ll all matriculate at some point.

KM: I appreciate your ability to write consciously, critically, and at times, unglamourously, about modern spirituality. I’m thinking particularly of the poem “Berkeley Hills Living.” How has your relationship with spirituality evolved through writing this book?

JL: “Berkeley Hills Living” was one of the first poems I wrote for the book. At that time, I had become connected with a plant medicine community in the Bay Area, which is like saying that I got into tech in Silicon Valley or the entertainment industry in Los Angeles, but, clichés aside, this community became a deeply important healing modality in my life. The medicine ceremonies involved prayer, which is perhaps what drew me so strongly to them, since there was this spontaneous linguistic element that served as part of the healing. I had always thought of poetry as a sort of prayer, but then this other, more literal mode of prayer came into my life and, much as I loved it, it scared me. What if one would have to replace the other? When I wrote “Berkeley Hills Living,” I felt like I had found a way to put those two modes of prayer in conversation with each other, and that was both empowering and a relief.

KM: You capture this rub between privilege and spirituality—characters studying at one of the most prestigious schools in the country who attend tea rituals on weekends. I’m curious about your inclusion of Alan Watts’s quote from The Way of Zen. What’s your sense of, as he describes it, “virtue in the current sense of moral rectitude”?

JL: What I love about that quote is that he’s actually defining the word “virtue” as against its moral or ethical connotation, so, in this case, against whatever moral shaming might be applied to privileged people who are trying to heal the universal human afflictions that no amount of money or education can help. He specifically says he doesn’t mean “virtue” that way, in “the current sense of moral rectitude,” but instead “in the older sense of effectiveness, as when one speaks of the healing virtues of a plant.” I love this idea that a thing’s “virtue” is not its capacity to be good, but its capacity to be most itself, or to most effectively do whatever it’s here to do. This is related to another question that is always somewhere at the center of my inquiry, which is: Are you seeing something clearly if you’re making a judgment about whether it’s good or bad? Or, put differently: Might moral judgments impede clear seeing?

KM: The title poem, “The Goner School,” uses first-person plural pronouns like we and ours that point to a collective youth suspended in time. How did you think about adolescence while writing? What did you do to connect with a younger version of yourself?

JL: I discovered that I had enough distance from my younger self to write about it. Uta Hagen, one of the great teachers of acting, instructs that if you’re in a scene where an event is happening that you have never experienced personally, you must find a substitution for that event, something from your own life that you can draw on to reach the emotional state the scene requires of you. But what’s most memorable to me—she describes this in her book, Respect for Acting—is when she talks about how it’s a kind of mystery, the things in your life that become available for substitution or not, she talks about how it has to be something you’ve worked through enough to be able to use. You can’t use as a substitution something you haven’t processed, even if you try. So what I’m saying is that in writing The Goner School, I discovered that I was no longer terrorized by my adolescence, that it had become something I could use.

As for lumping everyone else in with me, I know that there can be a risk in using the plural first-person pronoun—a sense of, how dare you speak for me? The use of we is a sort of contemporary poetry taboo, or certainly it felt taboo at Berkeley. At the time I was writing the poem, it gave me great pleasure to allow myself to use it.

KM: While reading The Goner School, I was reminded of the idea that the mundane is divine. Did that come up for you while writing?

JL: If it did come up for me, it would be as a kind of analogy: the mundane can be divine in the same way anything at all can be material for a poem. I never expected to write a long acrostic poem repeating “JESUS CHRIST,” for example, but I did. What a mundane and divine name that is, an invocation and an eye roll. Also, when I was writing that poem, “New History,” the fixed constraint allowed me to say things I wouldn’t have otherwise said. In a way, it felt like the first poem I’d ever written where I was speaking in my own voice, but it was still a poem: mundane and divine. I hope I can continue to find openings like that.

KM: In the poem “Fun,” the narrator asks, “What are things that merit mourning?” How did you interact with mourning while writing this book?

JL: I think of a Mark Leidner aphorism that says, “One does not begin a poem, one abandons one’s life.” At times, I have resented poetry because it feels like there should be something more worthwhile to do, but there isn’t, so I keep writing. If poetry is an act of mourning, it is also and equally an act of praise.

KM: The book feels emblematic of a generation. You write about student loans, intergenerational trauma, and apathy, for example. I’m reminded of a resonant moment in “The Breakfast Eaters” where the narrator asks, “How does life begin again?” while eating poached eggs on a ciabatta bun with avocado substituted for bacon. What do you make of that?

JL: Isn’t that breakfast’s eternal question, though? How to begin again? But also, of course, when you put something in a poem, even a breakfast sandwich, it suddenly takes on its maximum amount of resonance. You decide what to put there, what you gift with that resonance, but it’s not always your job to decide what it means.

KM: Poems like “Numbers” and “Consecutive Preterite” are profoundly personal yet gesture toward generational shifts in thinking around racial and religious identities. I revisited the question posed in “Numbers” many times: “Where was the love story?”

“Numbers” is a revisiting of the twelfth chapter in the book of Numbers, which was my torah portion for my Bat Mitzvah in 1999. It’s the story of Moses marrying a Cushite woman, and his siblings, Aaron and Miriam, resenting his choice and his chosenness. When I read it now, I see that we are like Moses’ family in the story. We meet his wife when he brings her home, not when he falls in love with her, because the story is not about their love—and maybe marriage, then, wasn’t so much about love either, but about the consequences of his marrying someone outside of his tribe. As I’ve gotten older, I’ve come to appreciate Moses more and more. He’s someone chosen by God to be God’s conduit and to represent and lead his people, and yet he is so far from perfect. In fact, he is full of rage. But much as he acts out and alienates himself, he can’t seem to slough off his duty, his “virtue,” to use that word again, his usefulness. I’m having trouble saying this concisely, and I’m not even sure the poem says it, but that’s the love story the poem is interested in: the way your human duty clings to you, as though it loves you back.