PoNW’s Favorites | Autumn 2025

Shade is a Place by MaKshya Tolbert (Nov., Penguin) presents a dynamic, refreshing poetics of shade, which is not only one place but many places at many times. This debut maps a politic of the tree (its policing and logging), of the tree-walk, and the aesthetic of any tour: the human gaze’s violence, the surprising solidarities. The relationship between writing and trees is questioned and transformed: what is written about and around trees, and the language of trees (quiet and changing) and the language imposed on them (like stress, thinning, relief, ancestry, and crown). The tree and its shade can describe, maybe even explain, all relation: from “I learn to take / my center / with me” to “Can I / Keep the gentle fence of myself?”

Stay Dead by Natalie Shapero (Sep., Copper Canyon) assumes apocalyptic means and their strange depictions, including American capitalism. Spanning the necessity of performance, the guarding of art, and the ubiquity of plastics, Shapero’s poems never relax, never let up. As in high comedy, what can be perceived as breaks are not minor lines but controlled moments that build tension towards where attention leads next: “Promise me / no posterity, nothing extractable, no record…and maybe—I said maybe—I’ll look your way.”

Blue Opening by Chet’la Sebree (Sep., Tin House) is formally and emotionally alive on every page, reaching for understanding, not knowledge, for relief, not certainty. The poems find that fertility, medicine, and bodies are, too, forms, received and renewed: “I am pregnant with grief—” The beautiful volume complicates what are often viewed as beginnings—Eve, baptism, etymology, womb—into the more complicated reality of openings: their wounds and futures.

Onement Won by Prageeta Sharma (Sep., Wave) is a woven text, inviting to threads and echoes. As with her first book, there is more than one kind, or level, of loss in each poem: a difficult friendship’s end, places, desires of youth, the secrets in a dead person’s left behind items, attachments to philosophy, a stepmother’s role, the beloved partner. At the heart of the book, grief lives in language and imagination even as it is fated to be untranslatable: “I found both abstraction and pain” and “Abstraction helps me think about concrete things.”

The Natural Order of Things by Donika Kelly (Oct., Graywolf) is sure but various, exuberant but controlled, traveling by cardinal directions, in time, and across dialect. With two revelatory collections famous for their cohesion in both content and form, Kelly seeks out a more profound wholeness in her marvelous third. Poems respond to performances, exhibitions, and workshops, feeling collaborative and born of pleasure and challenge. In one conversation with a great-aunt, “well” is punctuation, offering, and redaction all at once: “the two of us a chorus of well” and between them also what it contains and discards. The figures are daily—sex and aloneness, dogs and water—but their renditions make syntax feel like invention. The speaker considers return but refuses a return to the South, to received ideas of home, and to people, turns instead to water, the body, and speech. “There is no place I return to but the mind” she writes in a later poem. Readers are lucky to overhear this return.

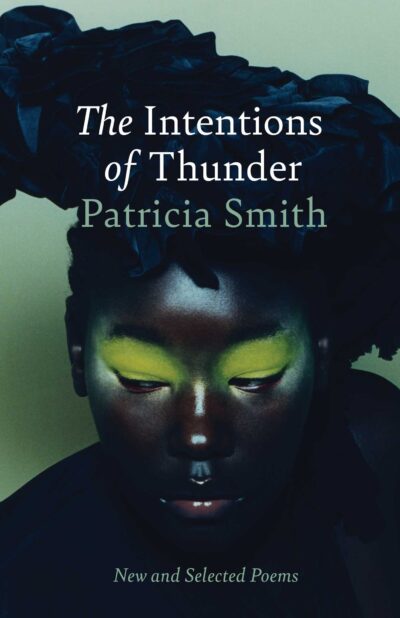

The Intentions of Thunder: New and Selected Poems by Patricia Smith (Sep., Scribner) is much like its author: abundant, brilliant, and unprecedented. Each book’s selections are introduced in rhythmic vignettes, which add surity to the impression that as time went on, poetry’s possibilities multiplied because Smith multiplied them. Smith also includes a jewel trove of uncollected poems and new poems, one of which ends: “I write, I love, I break apart. / I wrote. I loved. I broke apart.”

Study of Sorrow: Translations by Shangyang Fang (Oct., Copper Canyon) brings various Song Dynasty poets into a wide and cohesive narrative that feels more like a gathering under the poet’s admiring guardianship. His non-literal translations are agile and timeless, and his postscript discusses his choices with verb tense, story, and length (clear from this bilingual edition). The arresting essay also discusses memorialization or internalization in Chinese education and how the words recombine and appear to him as he writes and teaches primarily in English, as well as the many poems Fang did or could not translate.

In Trying x Trying by Dora Malech (Sep., Carnegie Mellon), language’s challenges are their pleasures and vice versa. Packed, sure, and pulsing poems make of description an alluring art; a typo as “My loss, less art / than craft” or a walk in the pandemic wherein “I get some distance, keep my distance.” A poem on miscarriage ends “Nothing, but much bloodier,” toddler pronunciations remind that “what / shatters is what’s growing as we speak,” and a stop sign recalls she who “could wait / for no mandible nor manager nor manna nor mention.” “Some days, / I feel like I’ve never encountered a noun,” reads a poem called “Nesting.” Sometimes when reading any original, energetic page of Dora Malech, there is an uncanny sense that it must be the first poem ever written or read: the witness of language’s very invention.

Penitential Cries by Susan Howe (Sep., New Directions) opens elegantly with “Each morning rapid heartbeat. Scattered alphabet.” The slim volume of four sections beats calmly through the scattering of lines and letters in long lines and collages of text. With recognizable sparseness and strangeness, Howe wonders and enacts how language becomes archive in real time: “Tacking against the winds of time I can only cut and quote.”

—Edited by Nanya Jhingran and Cindy Ok