PoNW’s Favorites | Winter 2026

Poetry collections to wander, want, and whirl this winter:

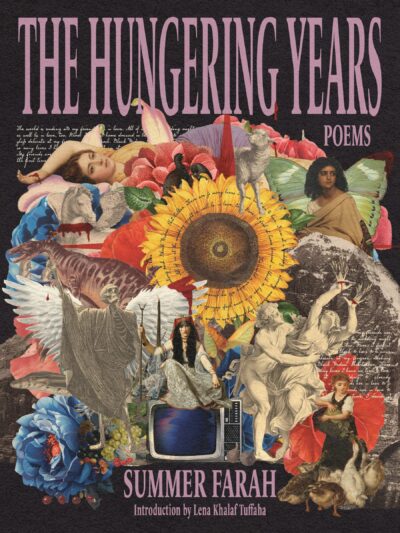

The Hungering Years by Summer Farah (Host, Feb.) has an electric pulse both steady and sudden, dense like the tightness of the back and jaw and vivid like their impossible release. This debut full-length collection accepts and measures the price of self-knowledge, stories, and laughter, to be inside of thoughts or water or horizon: museums are marked by steals and body counts, the names of things declare their control. Colonial tolls reorient the costs of borders and Zionism when the speaker, so in love with much read, heard, said, softly asks: “I wonder about the life stolen from me. Would I love what I love if I loved it from Palestine?” For Farah, to remember before is to remember the land itself, time and space wed in alive, exquisite poems.

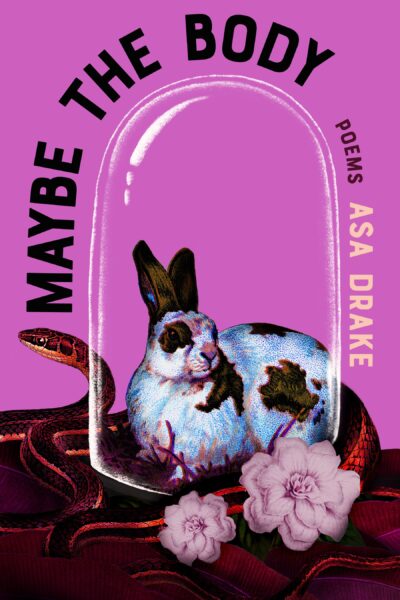

Maybe the Body by Asa Drake (Tin House, Feb.) is whole with the reconciliation of the titular “maybe,” its hopes of wonder leading the way. The speaker finds surprising the smallest acts of others, marveling at the daily colonialisms of names and silences, the changing systems of debt. One poem takes place in a river below an interstate, and other such efficiently strange meetings populate the sage collection; food and body, translation and transcription, library and garden, and, crucially, work and home: “Someone else’s / mysterious labor” palpable in the landscape between.

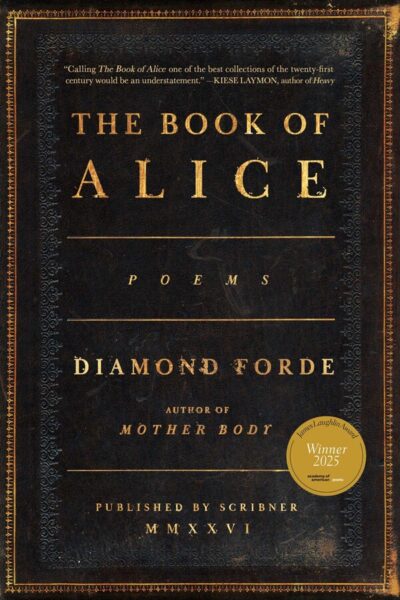

The Book of Alice by Diamond Forde (Scribner, Jan.) is a book written into and from a specific book object (a beloved Bible) and written of all books that rule the past and the present. Alice is the beginning and the end, the hope as well as the fear: “Grandma, I’ve lived / because of you,” reads the last poem. The original structures (with sections titled from Genesis to Revelations) become walls to resist into couplets, stories to break into charts or recipes. Forde’s project is marked by humor and fervor.

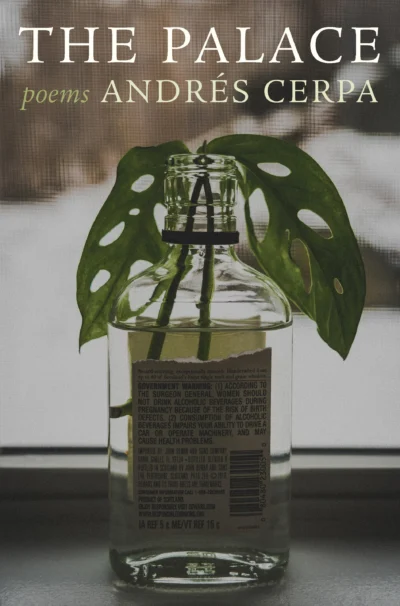

The Palace by Andrés Cerpa (Alice James, Jan.) is a new kind of flaneur’s roam with a calm sense of inevitability. It steps into time, through city, by myth, moving through loved ones dead and alive, through places held in memory. Each worldly worry is counteracted by the grounding of earth’s touch: fog sharpens sight, hauntings echo heaven, and maps loosen place. Saving money seems to make its absence more obvious. Like Cerpa’s first books, these poems embrace and shout out the influences of other poets from direct epigraphs to subtler nods.

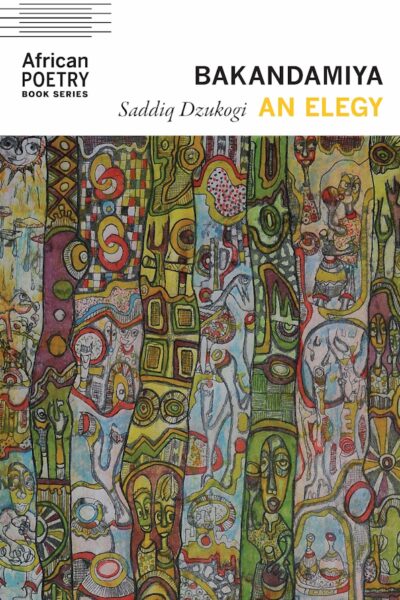

Bakandamiya by Saddiq Dzukogi (Nebraska, Dec.) is a graceful song of history, myth, and love. The much-anticipated second book understands religion as a potential tool of colonization in poems of indigenous spiritual practice and poetic tradition. Dzukogi takes in orality as the heart of a history that refuses Eurocentrism, brings in praise songs, hunter songs, the Quran, and even dialogue between an animist Bori spirit and Nietzsche. A lamentation and a rewriting, the past itself sings.

—Edited by Nanya Jhingran and Cindy Ok