Rochelle Hurt: “Bright star of disaster”

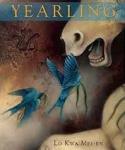

Yearling

Yearling

Lo Kwa Mei-en

Alice James Books, 2015

Lo Kwa Mei-en’s debut collection of poems reads like a manual for self-destruction. There are a variety of personal and global apocalypses in Yearling, and most of them are rooted in what Freud might have described as a death drive. The book’s epigraph from Dickinson, suggests, however, that these apocalypses should not be read simply as endings, nor should this drive toward death be read as a form of despair. The epigraph reads: “The World is not Conclusion. / A Species stands beyond—”. In this world, catastrophe is a means of becoming a species beyond.

Consider, for example, “Arrow,” a poem that positions the speaker as both predator and prey. Aptly, the poem strikes a tonal balance between divulgence and declaration, beginning: “Drawn, uninvited, I’m an animal with a price on her head, / wrecking a bed of wet pine: I steal through the field twice.” The hunted is also the criminal here. Audacious in her trespassing, she is both vulnerable and cheeky. She implores her addressee: “as long as the day is a shot yard of light, let me scope you,” conjuring an image of the startled deer overlaid with the slang of seduction. In this context, the poem’s title calls to mind the weapon of Eros and his violent game of desire. By the poem’s end, the speaker confesses: “A kill is what the heart calls its instrument hurrying on home.” The metaphorical kill is not the goal in this game, and, as the speaker knew all along but her reader is only now realizing, it never was.

Turbulent romance is one of Yearling’s topics, but it also covers a range of other experiences, from family history to personal addiction. Divided into three sections, the collection examines desire, conflict, and transformation through the lens of fairy-tale figures, apocalyptic myths, and prophetic creatures. Nothing seems quite literal in this book, and it’s richer for that. As the title Yearling suggests, Mei-en often invokes animals in the name of metaphor, teasing out rich parallels between animality and humanity. Take, for instance, the analogical implications of the following poem titles: “Rough Husbandry,” “The Extinction Diaries: Psalm,” “Prodigal Animals,” “The Second Flowering of the Mammals,” “Reader, Fauna,” and “Man O’ War.” The wordplay of the last, a reference to the champion racehorse by the same name, marries Mei-en’s animal schema to the idea of battle, a prominent motif that emerges in the collection as the speaker repeatedly arms herself for wars waged by and against her.

The need for armor—emotional, intellectual, linguistic—can be understood in the context of this book’s attention to the body as both a liability and a source of power. Both aspects are linked to desire, which is almost always described in visceral terms: “Love, the great butcher, kept us flesh as hell, diving // for dark terrain, but who can swim with open arms?” Water is yet another motif laced into these poems, and it is the most fluid, signifying journeys and transformation, as well as both danger and nourishment. “Water, I want you” actually reads like a love letter to water, conflating the body’s needs, the heart’s wants, and the mind’s will.

The question of physical desire (to act, to react, to survive) is taken up in one of the collection’s serial poems written to and in the voice of Pinnochia, a female embodiment of the famous boy-puppet who was granted a real (human) body only after receiving love. One of Mei-en’s most stunning poems, “Pinnochia from Pleasure Island,” uses a palindrome form to examine memory, reality, regret, and, fittingly, control. It’s organized into seven stanzas of six lines starting with alternating indents (already suggesting a back-and-forth movement), but after the first twenty-one lines (A-U), it repeats each line in its entirety, backwards, moving from T up through A, with U being the only non-repeated line. It’s tempting to see this as a mirrored form, used to underscore themes of reflection and identity, but it might be more accurate to call it a stitched form. The poem weaves a story down the page, then circles back, closing each loop as it works its way up—a hem.

Given the context of the poem, this movement can even be read as a binding action. Pleasure Island is the Disney film version of the original Adventures of Pinocchio’s Land of Toys, a place where boys can indulge in endless fun and bad behavior. After being lured there, however, the boys are turned into donkeys. In the Disney version, the donkeys are then traded and sold off. In Mei-en’s poem, this pleasure trap manifests as a dark, sexually charged exercise in power play. The speaker, true to her name, is physically manipulated in a series of actions that look like a stilted and even forced version of intimacy, which is itself a form of violence:

Now you make me dress

the wound I turned myself into when I bit into two.

Now you might get up inside it and show me the whip

-stitch anew, or finger-test my tourniquet, bandwidth.

The form’s likeness to a binding stitch pattern can then be read as both a trap into which the speaker has fallen and a form of protection she creates after the fact—a sealing of the self inside the poem.

Yet she is able to gain some control of the situation through formal maneuvers. The pivot occurs just as the poem begins to turn back on itself and repeat its previous lines: “Because here, somebody can open their mouth wider / yet. Laws don’t break here. It’s like I can still break / because here, somebody wants to open my mouth, wide.” In order to break, one must be whole (and here, perhaps also ‘real’), so the speaker’s phrasing suggests that, because of the lack of control in this setting, she can behave as if she is real, whole, autonomous—yet this condition actually makes her more vulnerable to the violence of control. After this turn, the evolution of some of the poem’s repeated lines suggests a shift in the dynamic between speaker and addressee. “Now you like / to know my real name” becomes “You don’t get / to know my real name,” and “wet me” becomes “Whet me,” implying a readiness for the speaker to become the dangerous one. In this way, the form also allows the speaker to retrace the events told in the first part of the poem from a new angle, rewriting “what [she’d] die to forget,” and finding some agency in the process.

Linguistic play is a means of agency in many of the poems in Yearling, but especially in a series of “Era” poems, which employ some of the quickest and densest wordplay in the collection. They are dazzling poems in which the trajectory of intention can be traced from “a matter of choice” to “a master of choice.” In their precision and wit, these poems live up to the book’s invocation of Dickinson, and even channel Plath (as does “Ariel,” the opening poem). The speaker takes pleasure in the sonic sharpness of her own lines, even as they are used against her: “Half always hawks // me back up, does the land I love but always a red-throated // rapture this way dives. Brutal my thermal drop.” A reader gets the sense that every word here has at least two meanings, so the speaker’s tongue might be in her cheek even as she approaches death.

Although her influences are audible, Mei-en’s voice is still distinct—it’s slangy and a bit dirty. This is Dickinson and Plath in a tumbler with a shot of whiskey, and ultimately, that’s what drives the collection. Even in persona, there is a coherent ethos at work. The speaker is perpetually poised to fire like a gun, and when she does, she revels in the linguistic consequences. Yearling sets a reader up for pyrotechnics from the start, and it delivers. One of the first poems declares: “O bright star of disaster, I have been lit,” and by the end of the book, the speaker is spectacularly on fire: “temperature and light, so hot, so real, I come alive.”

—

Rochelle Hurt is the author of The Rusted City, a collection of prose poetry and verse published in the Marie Alexander Series from White Pine Press (2014). Her work has been included in Best New Poets 2013, and she has been awarded literary prizes from Crab Orchard Review, Arts & Letters, Hunger Mountain, Tupelo Quarterly, and Poetry International. Her poetry, fiction, and nonfiction have also been published in journals like Crazyhorse, Mid-American Review, The Southeast Review, and Image. She is a PhD student at the University of Cincinnati.

Read a new poem by Lo Kwa Mei-en, “Passion with a Cinema Inside of It”.