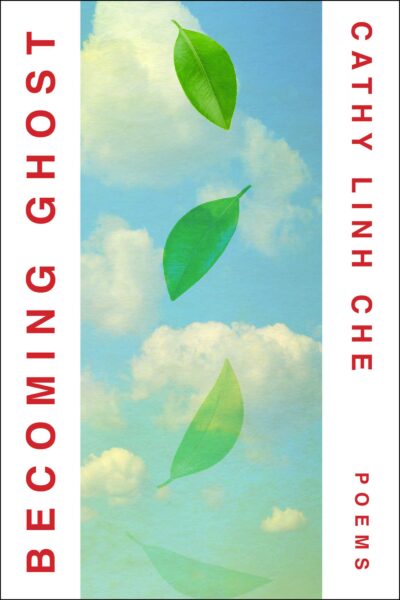

We Give it to Ourselves: On Cathy Linh Che’s Becoming Ghost

Becoming Ghost

Cathy Linh Che

(Washington Square Press, 2025)

Many years ago, on the road for work while trying to organize workers, I was driving through darkness somewhere in Oregon or southwestern Washington state when a woman came onto the radio. “I get into rooms sometimes,” she said, “and I say to the audience, who wants world peace? Who wants an end to war? And everyone raises their hand. And then I say, what about your own family? Who will commit to making peace there? And the room goes quiet.” My attention had been fuzzy before. Suddenly, it became very clear.

I was reminded of this experience while reading Cathy Linh Che’s new collection Becoming, the follow-up to her much-celebrated debut, Split (2014), winner of the Kundiman Poetry Prize, among other national awards. Becoming Ghost takes as its subject the author’s family’s journey from Vietnam to the United States through the Philippines, where, incredibly, they were cast as extras in Francis Ford Coppola’s 1979 film Apocalypse Now. The result of Che’s efforts is a revelation. Harrowing, lyrical, surprisingly restrained at times while also fiercely visceral, Becoming Ghost is, above all, courageous in its willingness to confront the conflicts within the author’s own family without letting the world off the hook. It was the world’s conflicts, after all, that led her parents to vacate their ancestral lands in favor of the United States (Che was born and raised in California). Whatever faults exist within her family, Che suggests, must be understood within the context of world-historical events.

Many voices and characters occupy Becoming Ghost, but the poet’s father looms over these poems the largest. In We Were the Scenery (2024), a short film Che wrote and produced about the same subject, her father appears gentle or even goofy—a bit of a know-it-all, perhaps, but basically harmless. In the poems, we see a darker aspect. His violence can take the form of abuse: “I watched my father switch my brother to bits,” she writes in one poem. More often, however, his anger seems to be directed at himself: “We stood barefoot on the street, / listening to my father smash / against the garage walls.” Che’s initial response to such dysfunction seems to have been to flee or to retreat into herself. But those approaches have their costs—namely, alienation, atomization into a single self. In one way, Becoming Ghost can be read as a reckoning with such strategies of self-preservation. The path to healing runs back to the family, she comes to realize. The only way out is through.

In many of the poems or sequences of poems, the speaker’s perspective alternates with that of her mother or father. The cumulative effect is one of empathy. We see Che with her “sealed-in loneliness,” but we can hear the voices of her family members, too. “Daughter, I think you embellish what you don’t know,” Che addresses herself as her father in “Bomb that tree line back about a hundred yards. Give me room to breathe.” “I taught you to count to one hundred / in Vietnamese . . . I tried to give / you the safety I never had. And now, you tell me / that you are afraid of me?” In this poem and in others, her father’s pain is palpable, complicating the portrait we see elsewhere. Her mother, though quieter, has a powerful presence in these poems, too. She is not just a “beautiful, dutiful wife,” as Che has her describe herself in “Zombie Apocalypse Now: On Love”; she is a person who has survived war, cultural and geographical displacement, and a difficult marriage to arrive, somewhat miraculously, in a stable life in California. She drinks a “single can of beer” with her husband on Sundays, raises basil, lemongrass, and guava in her garden, extracts the last bits of value “from the oozing meat / of a copper penny.” Despite the world-historical events that have come crashing down on her, she has managed to live a full life, with all the joys, struggles, and indignities that entails. “America, look,” writes Che, “at my mother’s face, and love her.”

In both We Were the Scenery and Becoming Ghost, we see Che’s parents take a practical view of their experience working on Apocalypse Now. They point out that they were paid twelve or thirteen dollars a day, which was far more than they would have earned working jobs in Vietnam; they joke about Coppola’s strange habit of eating mangoes without removing the skin. For them, the experience seems to be little more than an amusing anecdote in the ongoing story of their rich and complicated lives. For Che, though, the erasure of her parents and the other Vietnamese refugees from the film (they were given no lines, and they did not receive closing credits, despite appearing in key scenes) speaks to the larger silencing of Vietnamese people from histories of American imperialism and immigration. If, in one sense, the poems in Becoming Ghost can be read as narrating recovery from family trauma, in another they themselves work to recover narrative, recentering Che’s family and other Vietnamese people whose stories have been lost, forgotten, or ignored. In Becoming Ghost, Che elevates the so-called extras into protagonists.

She does this, in part, by repurposing language from Coppola’s script. Employing a poetic form invented by Terrance Hayes called “The Golden Shovel” in which the last word of each line forms a secondary poem that descends vertically down the page, Che redirects dialogue from Apocalypse Now to create poem inside of poem where Vietnamese experiences are central. One senses, through these textual manipulations, the author unlocking something within herself. She may not be able to fully forgive either her father or the famous American director who exploited him, but she can tell a different kind of story. She can write her own version. Of forgiveness, she writes, “It’s a condition of forgetting, / a stitching of one kind of life to another.” Ironically, it is the condition of remembering that has allowed her to create Becoming Ghost, a work of art that will forever alter, in my mind, the meaning of one of the most renowned American films ever made about the US-Vietnam conflict. “America, you ask for our light,” she writes in “Dear America.” “We give it to ourselves, our loves, / our kerosene hearts lamp-lit / for the children to come.”