Against Invisibility and Erasure: Light, Love, and Touch

by Christos Kalli | Contributing Writer

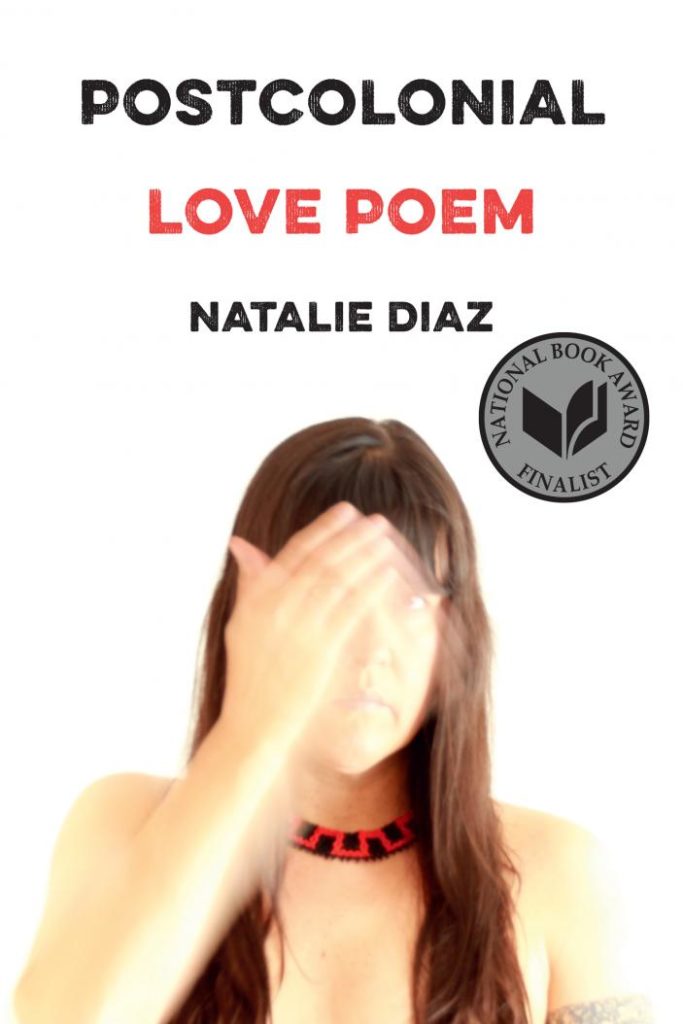

Postcolonial Love Poem

Natalie Diaz

Graywolf Press, 2020

In her introduction to the long-overdue anthology New Poets of Native Nations (2018), the editor Heid E. Erdrich, herself a Native American poet, begins by welcoming us in the “brilliantly lit dimension” that her selected poets collectively create and occupy. The Mojave poet Natalie Diaz, who contributed to this anthology with earlier work, has now written a book that not only enriches this luminous dimension but that is, itself, filled with light. In Postcolonial Love Poem, her light—repeated seventy-seven times and appearing in the titles of the poems “Skin-Light,” “Blood-Light,” “Ink-Light,” and “Snake-Light”—is erotic, familial, and linguistic, but always bright and always polemically cast against invisibility and erasure, as the poems come together (under the auspices of the title, not Postcolonial Love Poems but as a single Poem) to form a fearless beam. This righteous fight began in Diaz’s first book, When My Brother was an Aztec (2013), which deservedly won high praise and many prestigious awards for elegantly weaving lyricism and lived experience. No longer a “new” poet, at least not in Erdrich’s debut-writer definition, Diaz here hones the voice that made her unique and raises the stakes: in the postcolonial world that she inhabits, and that is sometimes forced upon her, visibility needs to be manoeuvred and managed just as vigorously as invisibility.

Survival and erasure, visibility and invisibility, sometimes coexist seamlessly in Diaz’s poetry and amongst the remnants of colonialism that it constantly encounters. In the first section of her collection Diaz situates the reader in a museum, a complicated historical site for anyone, let alone a Native American.

At the National Museum of the American Indian,

68 percent of the collection is from the United States.

I am doing my best to not become a museum

of myself. I am doing my best to breathe in and out.

I am begging: Let me be lonely but not invisible.

(“American Arithmetic”)

Financial and political agendas aside, the general premise of all museums is, at least at face value, admirable: each one operates as a sanctuary that maintains, elongates the life of, and, in the process, exhibits historical, artistic, and cultural artifacts. However, because otherwise invisible objects become visible only transiently and within a limited space, it is their real-life invisibility that is highlighted in the end, and while their survival makes a fleeting impression, it is their erasure that stays with the visitors. The National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI) preserves this duality but its fraudulent historical combination of “National” and “Indian,” colonizer and colonized, provides another layer. “[F]or some the NMAI stands on the National Mall as a reminder of Native endurance from invasion, imperialism, and modern nation building,” writes the anthropologist Robin Maria Delugan, “for others, it signifies the destruction of Native sovereignty and the cooptation of Native cultures in a gesture of nation-state largesse.”

Diaz’s carefully crafted lines do much more than highlight this dichotomy—they portray how a postcolonial world that is littered with copious reminders of co-optation and endurance, requires resistance and survival to operate, necessarily, on many levels. “I am doing my best to not become a museum / of myself,” she writes, with a line break that is powerful enough to produce multiple interpretations at once, and, at once, break and mend your heart. In a country that marvels at Native American history only when it is behind a glass, in a country that is trying to enlist Native Americans as a scant portion of its own history, not becoming a museum—not joining your eliminated ancestors, not being stored and exhibited as gone—is a powerful act of survival. Beyond the line break, as we turn and reach “[her]self,” her resistance becomes wholly against a transformation that is intrapersonal and metaphorical. She is doing her best not to become a museum herself, a mere structure in which the ancestral past is hoarded. The line indicates a continual survival but also suggests the apt coercive forces that make this constant effort to survive necessary.

As part of a dynamic group of Native American poets—including Shonto Begay, Trevino L. Brings Plenty, Julian Talamantez Brolaski, Jennifer Elise Foerster, and Layli Long Soldier, writing at the same time across three generations—Diaz is not the first who has examined museums as intersections of one’s own visibility and invisibility. In Nature Poem (2017), Tommy Pico overhears a dialogue between two white ladies in the Hall of South American Peoples in the American Museum of Natural History:

it’s horrible how their culture was destroyed

as if in some reckless storm

but thank god we were able to save some of these artifacts—history is so

important. Will you look at this metalwork? I could cry—

(Nature Poem)

In his characteristic piercingly ironic style, which compliments Diaz’s stern lyricism and exemplifies the stylistic diversity within this canon, Pico says so much based on this brief encounter. The instance in which Native Americans and their history become visible to the white ladies is undercut by their deep-seated, internal blindness: a fragile grief, a superficial appreciation, a white savior complex, a selfish and reductive understanding of history. Pico turns the mirror towards these women, and he is almost glad that they will never be able to dissect their blindness while he and, hopefully, we have or will.

In Postcolonial Love Poem, Diaz goes one step further: she constructs her own museum with “exhibits from the American Water Museum.” Inspired by Luis Alberto Urrea’s short story collection The Water Museum (2015), as the Notes section explains, her poem-museum hybrid synecdochically poses as the whole book and presents a grand structure for the reader to dwell in. Her museum, unlike National museums, prioritizes the principle of freedom (“The guidebook’s single entry: // There is no guide”), puts at the forefront Native American mythology (“Out of this opening leaped earth’s most radical bloom: our people—”), displays (white) indifference exactly for what it is (“Dial 1 if you don’t care”), and exhibits America to be seen clearly as the culprit (the “American way of forgetting Natives”). At ten pages, “exhibits” is the longest poem in a collection full of mid-length ones. Diaz is an excellent practitioner and lover of lyric sequences, utilizing the space they permit to construct elaborate architectures and museums of her own. Though erasure and survival inevitably walk side by side in this structure (if it is even possible to separate them without denying a portion of Native American history, which is a question that Diaz asks as well), the latter triumphs in the last three lines of the poem, which productively concentrate the longue durée of erasure and then eviscerate it: “Once upon a time there was us. / America’s thirst tried to drink us away. / And here we still are.”

As a self-proclaimed “Love Poem,” the collection’s greatest weapon against erasure and invisibility is desire itself, which Diaz portrays with a similar physicality as the construction of her museum. In “Isn’t the Air Also a Body, Moving?”, a lover touches another lover into existence:

I am touched—I am.

This is my knee, since she touches me there.

This my throat, as defined by her reaching.

(“Isn’t the Air Also a Body, Moving?”)

Divided into action and thought, or physical gesture and existential reaction, the poem quickly becomes an erotic creation myth. Whether an embodiment that alludes to Genesis, or a powerful reversal of disembodiment that undoes erasure, the poetic persona is not only seen by the other lover but put together as they and the poem progress.

With section epigraphs from the Native American poet and current Poet Laurette Joy Harjo, the late 20th-century Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish, the African American literary critic Hortese Spillers, Rihanna (referred to by her original name, Robyn Fenty), and the 17th-century Mexican philosopher and writer Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, it is clear that Diaz has been influenced by an array of creative thinkers. When desire is the protagonist, however, a distinctive influence is Audre Lorde, and especially her 1978 essay “Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power.” In Postcolonial Love Poem the erotic is power because it casts light and entitles presence (in “Skin-Light,” “Our bodies—: light-harnessed, light-thrashed”), because it makes visible (in “Like Church,” “Her right hip / bone is a searchlight, sweeping me, finds me”), and, as in “Isn’t the Air Also a Body, Moving?”, because it simply makes with the power of touch.

“I serve the kingdom of my hands,” Diaz writes in “The Cure for Melancholy Is to Take the Horn,” near the end of her book. And the hands of the poet in this collection have worked hard and have done a lot, for the reader, for this current moment, for her ancestors, for the poet herself. As a writer, as an architect, and as a lover, Diaz takes visibility in her own hands. In the process, Diaz has also taken the “Postcolonial,” relieved it from the academic associations that have been latched onto it the last decades, and bound it to a word that is very seldom next to. This is a love poem that has outlived colonialism—yet not its contemporary residues—and it is here to tip the scales towards survival and visibility.

—

Natalie Diaz was born and raised in the Fort Mojave Indian Village in Needles, California, on the banks of the Colorado River. She is Mojave and an enrolled member of the Gila River Indian Tribe. Her first poetry collection, When My Brother Was an Aztec, was published by Copper Canyon Press in 2012. She is 2018 MacArthur Foundation Fellow, a Lannan Literary Fellow and a Native Arts Council Foundation Artist Fellow. She was awarded a Bread Loaf Fellowship, the Holmes National Poetry Prize, a Hodder Fellowship, and a PEN/Civitella Ranieri Foundation Residency, as well as being awarded a US Artists Ford Fellowship. Diaz teaches at the Arizona State University Creative Writing MFA program.

Christos Kalli studied American Literature at the University of Cambridge. His poems have appeared in or are forthcoming from Ninth Letter, The Adroit Journal, The National Poetry Review, The American Journal of Poetry, Faultline, the minnesota review, PANK, The Hollins Critic, Harpur Palate, and Dunes Review, among others. His chapbook INT. NIGHT / Nightscarred was a finalist for the Sutra Press Chapbook Contest (2017/2019). From 2017 to 2019, he has served on the editorial board of The Adroit Journal and now he is an Associate Poetry Editor for Stirring. Visit him at christoskalli.com