Interview // There Isn’t a Metaphor for Everything: A Conversation with Jane Wong

by Jake Uitti | Contributing Writer

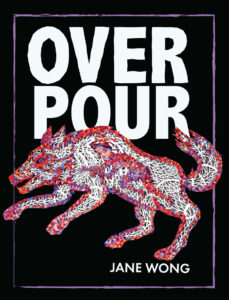

Jane Wong, the exceptional Emerald City poet, now lives and works in Bellingham as an Assistant Professor at Western Washington University. The daughter of Chinese immigrants, Wong graduated from the University of Iowa’s MFA program in poetry, and then earned a PhD from the University of Washington. Recently, Wong was also awarded a prestigious Washington State award. But perhaps more than anything it was the restaurant her parents owned and operated in New Jersey that shaped her career. We wanted to catch up with Wong—whose poem “Aphoristic” appeared on our website, and whose first collection, Overpour, was reviewed here by Dandi Meng—to talk with her about her recent award, how her past has shaped her present, and how she moves forward through a challenging and often dark world.

Jake Uitti: You recently won the James W. Ray Distinguished Artist Award. What can you tell us about that?

Jane Wong: I feel super lucky. It was announced in December and it’s for Washington State artists through Artist Trust, the Frye Art Museum, and the Raynier Institute. It’s a big honor for me. As a mid-career artist, I feel like I’m on the precipice of something really new and big in my work. After my first book, receiving this award was the extra push I needed to keep going, in terms of confidence.

Wait. You’re so accomplished! Is confidence a real issue for you?

I think all artists struggle with confidence in one way or another. For me, it’s a self-driven struggle in terms of making your vision happen. With my current two manuscripts, it’s about pushing myself creatively and formally. I guess I think of confidence in terms of being totally okay with risk-taking, which is something I enjoy but also find scary.

At some fundamental core, I’m a first-generation college graduate and the first in my family to finish traditional high school. I always think: “Can I do this?” and I’m always honored when people think I can. Confidence is a funny thing. For anyone who is an artist, confidence builds in waves. There’s always something celestial about it in some weird way. Confidence drives you even in moments when you don’t have it.

Can you talk more about this question you have internally, this “Can I do it?”

I have a desire to move around and explore in terms of creativity. Yet, this exploration is not necessarily comfortable. And I tell this to my students too: being an artist is about being uncomfortable and putting yourself in uncomfortable positions. That includes trying something radically different from other modes of your work or life. For me, it’s being able to look at the same thing—something that haunts you—from completely different angles and evaluate how that can deeply impact a reader. That, for me, often falls into the idea of form.

I’m writing nonfiction right now, which requires much more vulnerability and transparency, to some degree. Because there isn’t always a metaphor for everything. Sometimes this is just what happened. Not that there aren’t lyrical elements in nonfiction, but this genre is a total risk for me. I have to go towards it if I want to evolve as a writer.

Is your new nonfiction about your family?

It’s about many things. I have a few essays—one is coming out soon in Black Warrior Review—about unlicensed dentists in New York City’s Chinatown. In this essay, I write about how my mom would try and find illegal dentists because she didn’t have insurance. A lot of the pieces engage what it means to grow up as a low-income child of immigrants and “making do.” Thinking about upward mobility, in the next generation, I feel strangely guilty for that wild socioeconomic and cultural capitol difference. That shows up in a lot of my work; how do I connect those two gaps or three gaps of generations (and their histories) with where I am in my own life? There’s another essay about my father’s gambling addiction in Atlantic City. How casinos obviously target low-income communities, particularly people of color, by providing casino buses leaving from Chinatowns. Casinos have this promise of making it big, “rags to riches,” the American Dream. It’s all also about my childhood and growing up in my family’s restaurant.

Speaking of that, I wanted to ask a lighter question: what dish do you miss most from those days?

What I miss eating the most is not any of the food we cooked for customers. My mom would make me this very simple egg drop (or egg flower) soup that was quick to make when she worked, except it had corn in it. It was this hodgepodge of corn chowder and egg drop soup. Very simple. I’d drink that out of a Styrofoam cup. The food I ate there was on the fly, as fast as possible.

Did that dichotomy of what you served American customers versus what the family ate open your eyes to any sort of major cultural fissure?

I knew that there was a perceived understanding of what people thought Chinese food or culture was like… As I grew older, I started seeing food culture as more fluid than that, though. Not this is real and this is fake. I realize now that is not a fruitful dichotomy. At the time, though, I remember being very, very aware of how people saw our food. My parents didn’t necessarily hate the food they cooked for customers—it just tasted so radically different that they wouldn’t eat it. It had a lot of sugar, an added sweetness to the palate that wasn’t Cantonese.

But now I think there are some delicious things in Chinese American cooking that I would embrace. What is that stuff? General Tso’s Chicken? It’s really good I think! It’s not. But it is. I don’t know… Now, I try to break down questions about authenticity. Food is also a result of time and change. It’s still important to me to try and return to dishes rooted in a childhood memory. But, I also know that my mom probably has a unique twist on a Cantonese dish that’s not wholly “authentic,” based on ingredients she has or doesn’t have locally.

What’s one thing about the poetry world you wish would change?

For me, it comes down to kindness. That’s very general, but also very true. The poetry community is so small and yet so large; I want to see more kindness and realness in terms of interpersonal relationships and also in terms of the work. Kindness is something that’s always in the back of my head. Poetry and creativity can bring a lot of goodness to the world… Even if there is darkness, and there is, there is still an opportunity for kindness and tenderness. In my own work, I try to remember kindness exists even in such dark, violent, and traumatic times.

What are some themes you find yourself going back to in your work?

Definitely family. Metamorphosis, change. History—my family’s history in China in particular. The natural world. I’m always concerned or worried about our world, our environment. Even if it’s not immediately obvious in my work. Also selfhood and making sure one’s self is still ticking and alive.

You recently said you care about taking about histories that have been silenced or hidden. Can you expound upon that?

I think it’s really important, especially as a woman of color, to remember that our histories are often silenced—and these stories should be uplifted and given voices. It’s not something unique in my work, per se, but it’s across many works that I love and respect. For me, it’s going to be an ongoing lifelong project. It’s also a part of my Poetics of Haunting project, which was my dissertation. Those histories that haunt us are always there. Not in a way that’s negative, necessarily. I think of ghosts as protective and a part of my community. How could you forget ghosts or forget these histories? For me, a part of writing is doing that work, to make sure those who could not speak—for fear of persecution—could speak via me. But I also want to make it clear that I’m not a vessel. I’m deeply affected and my voice is there too. I can’t speak with or for the dead, but I can at least try my best to learn and listen to that history.

There are amazing writers like TJ Jarrett who write about the Middle Passage. The history of American slavery does not go away. It’s not meant to go away. To think it’s over and done is ridiculous. And it’s still silenced and pushed into one chapter of a history book in a 5th grade classroom. If you’re lucky. I like to think of poetry as a continued remembering of all that came before. It’s high stakes for poets of color to wrestle with those histories and also their own place in it. And it’s my honor to do this. It’s not a responsibility or a burden. It’s an honor that I get to write poems and move those histories forward. I’m very grateful.

What’s one boundary you’d like to push forward in your writing?

I think the biggest thing my nonfiction readers will notice—whether it’s obvious or not—is that I’m trying to be funny. I mentioned before that my nonfiction can be relatively dark—gambling addiction, illegal dentists—but I wrote these essays with the mindset of trying to be funny in addition to being difficult. That’s a huge risk. I’m an intense person, but I’m also goofy. I really wanted the goofy part of my personality to come out in my writing. It doesn’t come out in my poetry as much. There’s something about nonfiction where I feel more open to humor. I write in one essay, “I’m Jane Wong, motherfuckers!” because the scene was about feeling invisible. I’m also working on an essay about my mother’s fashion sense, her sartorial history. Dressing up is a big part of my life, weirdly. And that comes from my mom, who taught me to look good while trying to “make do.”

Can you share one writing secret that you’ve learned over the years?

One secret, which I tell my students: verbs. Pushing on your verbs. Being very precise about which verb you are using and making sure that has texture and weight beyond that which is surface level. Use very strong verbs. Like Gwendolyn Brooks and “whipped out the light” in “when you have forgotten Sunday: a love story.” Sometimes that means making up verbs. Making up a word like “mothing.” It’s a better verb than, like, just “going through.”

Jane Wong holds an M.F.A. in Poetry from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and a Ph.D. in English from the University of Washington. She is a former U.S. Fulbright Fellow and Kundiman Fellow. Her poems have appeared in journals such as Pleiades, The Volta, Third Coast, and the anthologies Best American Poetry 2015 (Scribner), Best New Poets 2012 (The University of Virginia Press), and The Arcadia Project: North American Postmodern Pastoral (Ahsahta Press). She is the author of OVERPOUR (Action Books) and an Assistant Professor of Creative Writing at Western Washington University.

Jake Uitti is a Seattle-based writer. His work has appeared in the Washington Post, Alaska Airlines Magazine, and the Seattle Times. He is fond of ramen, The Voice, and talking with people about their work.

Photo credit: Helene Christensen