Interview // The Dream of Suspension: A Conversation with Cedar Sigo

by Jennifer Elise Foerster | Senior Editor

I met Cedar Sigo in New York City in the spring of 2013. We were attending a conference at Poets House called Native Innovations: Indigenous American Poetry in the 21st Century. Listening to his poetry and craft talk, I was immediately enamored by his acuity and elegance. His poems were diamond-cut and his insight into craft was as prismatic as the poems’ refracted light. He and I both lived in San Francisco, so I was able to continue my marveling through lavish hours of poetry-gab. Over the years, talking with Cedar about art, poetry, and poetics while listening to jazz or walking the streets of the Mission, I have come to believe he is one of the most brilliant and dedicated poets writing today. I’m grateful to be able to share a splice of our conversation through this second edition of the Native Poets Spotlight Series.

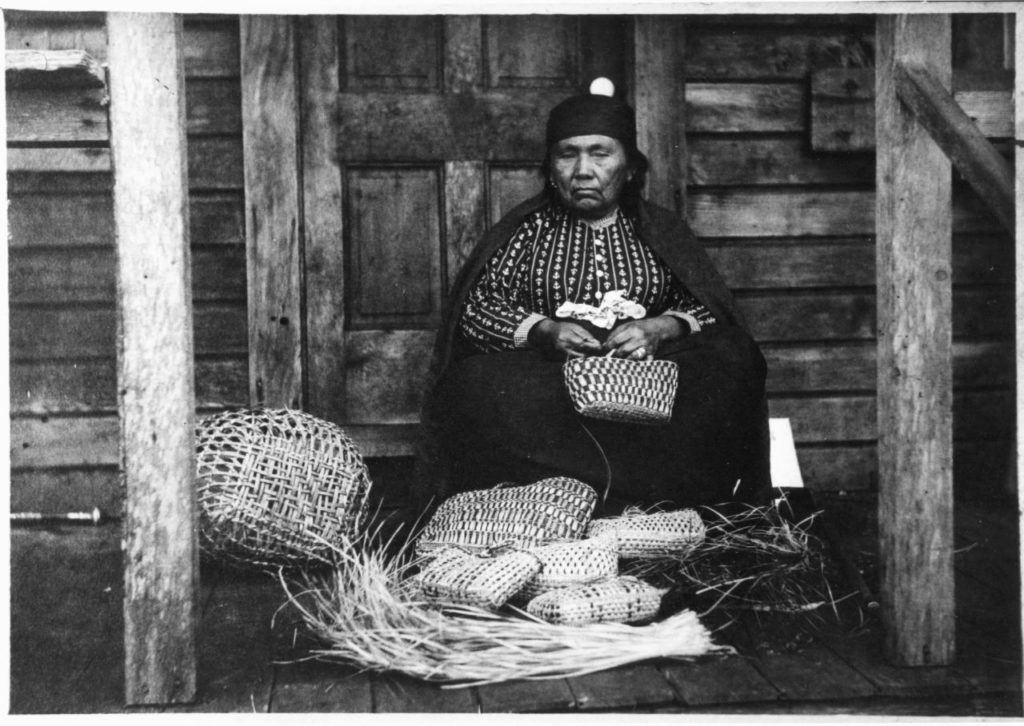

Jennifer: I remember when we read together at Poets House in New York. In your craft talk, which you titled, “Becoming Visible,” you spoke of poetry as a “broad element at play” in your culture, and compared it to basket making. Here is that beautiful passage, which was recorded at Poets House on March 23, 2013:

We are still known for our basket making. They are woven mostly from cedar bark, and within their bold, precise patterning, we often pay homage to the plants and animals of the Puget Sound. The bark goes through several stages of soaking and drying in order to become pliable. It’s hard to think of a process that could ever rejoin you closer to the earth. When people ask me that horrifying and somewhat common question—what is your poetry about?—I now think of the baskets, how they are about the material, and how the purity of the process imbues them with spirit. The poetry is also about its material—words—and the gaps that occur between them at the apex of composition. Hopefully the reader is left with an intensity with which they can link these several parts.

Do you still think of your poetry this way—that it’s about its material and the gaps between words?

Cedar: I wanted to address what it’s like to be a Native artist from a Native American point of view. Basket-making is a long process and involves a courtship with the materials. You have to gather the cedar at the right time, and sing before you do that. You soak the cedar and dry it so it can become pliable. I wanted to equate poetry to something formal, something that relies on edges, like a totem pole or carving, like the bent wood boxes from the Pacific Northwest. People often think of poetry as a dalliance or as a form of expression without the architecture that is required by some of the other Native arts, like carving, painting, or weaving. Ceremonial objects have this physical weight and grandeur, and the techniques explored in making those types of Native art are very honored. My intention in equating basket form to poetry is to honor that there is also a mastery to poetic form. In poetry, there are these luminous edges and techniques that need to be absorbed in order to become that master. When people look at a basket, they see structure and symmetry. But with poetry, there’s too often the assumption that there’s no structure because you can’t see it.

Jennifer: True. I wish more people could allow themselves to see a poem for its form and colors instead of closing their eyes to these dimensions. I think the making of a poem, and the way poets learn their craft, is as serious and meticulous a commitment as that of a master basketmaker. I like how you talk about the courtship in working with materials, whether this is language or water or wood. It reminds me of something you wrote in one of your blogs for Poetry Foundation’s Harriet in October 2010. This excerpt is from “Process Notes”:

Poetry has always been a matter of courtship for me. I have often felt as if I were waiting for it to appear, hoping for something epic (in structure if not always in length) or impressive I should say, vaulted ceilings, knowing you are on your way to build a monument of sorts.

I’ve been thinking a lot about invisible architectures in the making of a poem. You can’t see the making or feel the weight of its material, but there is a structure that is created, with windows of sorts, and vaulted ceilings, as you say. As the poet, you’re making something out of invisible materials.

Cedar: Yes, and you have to articulate your belief that that’s happening. The combination of vision and craft is so necessary for this belief.

Jennifer: Speaking of vision, I sense the “apex of composition” as a kind of visionary moment in the making of the poem. Is this what you mean by the “apex of composition” and the gaps that occur between the words at that point?

Cedar: That thing about being in the space of the apex, where the fragments, or gaps, could possibly join, that’s really talking about the dream of suspension in poetry—the physical idea that when you’re reading something, you leave a word spinning in the air that is dependent on the word you last took off from. I think that’s actually the impossible dream, because the fragments never quite get joined, like the negative space within the weave of a basket.

I think the most exalted form of writing is the editing. That’s where a lot of the magic takes place. That’s suspension. You get a lead of one line, then a lead of another line, and then you wonder—envision—how these two lines might belong together in this poem. My only indication that it’s going well or getting close to that initial vision is the transfiguration of time, which occurs most often during that shaping period. Time becomes dysmorphic; it behaves of its own accord. To lose one’s sense of time during the editing is my indication that I’ve gone somewhere, that the vision suits what I may have wanted. It’s almost like having a dream, and then making a portrait based on the dream. The dream state is so flexible.

Jennifer: It’s encouraging to think we might achieve the vision we wanted for the poem by getting out of its way. What’s the most challenging part of editing for you?

Cedar: Editing is craft, because you can go too far until nothing remains. That’s always the threat to the poetic process—poetry always wants to resolve and disappear again, and without our craft, we can go too far. If you don’t learn the way to climb the mountain, where the footholds are, then you’re awash in randomness. Finding one’s footing is a totally personal process, and it has to do with how you imagine the poem remains in the air, in your mind, after you close the book. Where does the line of sight change; where does it rest; where does it do a 360? What I mean to say is, it does come out of thin air. It’s not something I have a preconceived notion about.

Jennifer: There’s buoyancy to your lines; they live in the air. But I also know they are precisely planted and intentionally textured. I can move around in your poetry as one moves freely among fragments, as if there are many windows and doors and no determinate pathway through the poem’s space.

Cedar: A friend once told me the poems are pretty touch and go. It’s a good description; I do invite in the element of chance. I try to lose my own way. But at the same time, the poems demand presence. Their attention to the syllable and the layout on the page, all these things indicate permanence or a clinging of the poem to its own space. Sometimes I think I’m writing in certain patterns without even realizing it. If I recognize anything that can be tracked, I want to clear the deal. For example, I’m enslaved to the syllable. I think rhythmically but don’t want the poem to sound like that. I want it to sound like something dislocated—a limp rather than a grand walk. I want to disfigure my sense of rhythmic thinking. And if I feel I’m setting myself up to resolve a line too easily, I’ll take out a syllable. It’s the asymmetrical moment that’s preserved, that gets stuck in one’s head. There’s something charming about misremembering a line.

Jennifer: So if there is intentionality in the accident, how does your determination, as the craftsperson, the poet, engage with chance?

Cedar: There’s something in the poem—that touch and go aspect—lines I’m putting in randomly, inviting in that element of chance—that isn’t of my making. Inviting in that element of chance, you’re also inviting in the element of not knowing. I don’t know what I’m doing exactly. I don’t know how it’s going to play out. But I do think there are forces within that work that are beyond me, that will later “come true.”

Jennifer: As the writer, there’s quite a lot of suspension in not knowing where the poem is coming from or going. Do you think there’s a similar quality of suspension in the reading of poetry?

Cedar: Poetry is demanding; it requires re-reading and different voices. You reading a Robert Duncan poem aloud to me will sound differently from the way I negotiate the suspensions, and that’s what’s interesting to me about poetry—the way the voice rides the work. That’s the drama of it, to get the reading right. Poems are demanding to read not because of their content but because of their arrangements—the things they call into question about anyone’s voice, about the limits of the voice, about the accuracy and free spontaneity of the voice. When I read, I go somewhere else. I wish it were possible to read with your eyes closed, just to enhance that possibility, but I also wouldn’t want to get away from the page. Really my ideal would be to be a singer, jazz in particular; I try to sing through my work. For poetry, the drama is built in through words not gesture. The phrasing in my work I picked up from musicians like Billie Holiday, Pharoah Sanders, and Sarah Vaughan. The phrasing, the way things linger behind the beat, the modulations—these are things I obsess over.

Jennifer: You wrote about this in “Fragments Of A Disordered Devotion”—another prose piece for Harriet:

Live recordings of jazz singers seem to be my favorite soundtrack, I have always felt that we are up to the same thing, renegotiating an established melody, and taking all the time you need to share the way it fits to your own voice.

I’m interested in this idea of poems as renegotiated melodies.

Cedar: I think of my poetry like arrangements for the voice: the band follows the singer, not the other way around. Too few poets write arrangements that follow the voice. Most people just play a lot of melody. But poetry requires a lot of layering—there has a to be a background, and like the piano, a right hand and a left hand. If you don’t have those layers you just have melody. As a poet, you have to be the arranger adding in the many sets of voices. That’s why I like working with chance, working with whatever’s in the atmosphere to bring additional voices to the arrangement.

Jennifer: You’re a prolific writer, not just of poems but also of prose and lyric essays. You’ve been a featured writer for Poetry Foundation’s Harriet and for the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art Open Space blog, among others, and have written numerous articles and features on poetics and poets. Can you talk a little about your commitment to prose and how, or if, this merges with your identity as a poet?

Cedar: Poetry is a generative thing. It becomes a lifestyle, a cosmology. I think of that Charles Olson quote that I love, “Art does not seek to describe, but to enact.” I like to always be writing a prose piece. I love to write about poets and artists, and to write anything incidental, like intros or afterwards. I love to publish first books by poets, and getting students to start their own magazines where they can write and publish poetry and reviews. There’s a lot to be done, and I feel like we need to step up our game for the volume of the work we’re putting out there.

Jennifer: Yes, I think doing this kind of work, writing prose responses, reviews, etc., is a generative way to support the poetry coming out in the world. Part of enacting art is to interact with it in various ways, to help it reach a wider audience. We especially need to do this as Native writers—to write about one another, to enact our own literary criticism.

Cedar: Prose is very inclusive and exact. I want to be clear, and I don’t want to exclude anyone. Especially as a Native American writer, I don’t want to exclude my own people from my writing. But it’s a quandary. The only way you have a voice as a prose writer or art critic is to be an academic, which is exclusive. I mean, I’m an exception to that rule, but it’s not been without some perilous living.

Jennifer: Would you say one of your goals in writing prose, then, is to invite people into your poems?

Cedar: Yes, absolutely, but that doesn’t mean it’s understandable. It doesn’t mean it’s narrative. I think of myself more as an experimental filmmaker. If you watch a 12-minute movie by Stan Brakhage, Kenneth Anger, or Maya Deren, when the lights come up, you’re not going to be pressing for meaning. The meaning is just that the experience is an assault on the senses, and the meaning may not be present at the end of the performance. If you’re searching for narrative, you’re just like waves lapping at a rock trying to change its shape.

Jennifer: I often feel like you’re writing about poetry when you’re writing about a painting or a film. You offer, as a poet, a unique perspective for seeing and thinking through art.

Cedar: There’s a symbiosis between painters and poets. John Wieners was asked, “You’ve collaborated with a lot of painters,” and he responded, “Yes, I found them better company.” “Better company than other poets?” “Yes,” he said, “they were always too vampiric.” I always felt that way. Painters and poets, we live in different countries. And there’s a romance that occurs just as between two people from very different countries who don’t speak the same language. You just know and accept there are some things you won’t be able to understand about each other.

What we need to do with prose, and also through the forms we choose for our poetry, is to ignite poetry for people. The audience should want to write a poem. That’s where prose about poetry should be going, encouraging new writers and readers. Our challenge is to introduce the work of poetry with an allure, with light, with glamour. And it’s important, too, to bring people into the lives of the poets we’re reading or writing about, to let people recognize themselves and their humanity in other poets.

Jennifer: You just published two books almost simultaneously this fall: Royals, from Wave Press, was released in September, and you edited a collection of interviews and journals from the poet Joanne Kyger, There You Are: Interviews, Journals and Ephemera, also from Wave Press. Do you feel like you’re in a different phase of your work now from when you were writing Royals? What are you interested in now?

Cedar: I’m starting to take up more of the discontinuous narrative. I’m interested in the poem that doesn’t have to have a beginning, middle, or end. A poem can be a medallion within a longer piece. Longer pieces are just evidence of what gets you through being a poet—received texts that make you feel like the antenna is still functional. Thank god there’s no pressure to connect it all in the end. In fact I like making a long work from fragments, and just leaving it. That’s one of the essences of my work—I don’t feel the need to contextualize. Instead of a building up to an ending, I’d rather have something emblematic of an ending that haunts you. The “rejection of closure,” that’s totally me. If you have the base notes, you don’t need the “they lived happily ever after” ending. That last note is in the pocket. It’s there, for you to end on.

—

This interview and the following poems are the second in a regular series guest-edited by Jennifer Elise Foerster.

Cedar Sigo was raised on the Suquamish reservation near Seattle, Washington. He studied writing and poetics at the Naropa Institute in Boulder, Colorado and has lived in San Francisco since 1999. He is the author of eight books and pamphlets of poetry, including Royals (Wave Books, 2017), Language Arts (Wave Books, 2014), Stranger in Town (City Lights, 2010), Expensive Magic (House Press, 2008), and two editions of Selected Writings (Ugly Duckling Presse, 2003 and 2005). He is the editor of There You Are: Interviews, Journals, and Ephemera, on Joanne Kyger (Wave Books, 2017). He has taught workshops at St. Mary’s College, Naropa University, and University Press Books. He just moved back to Washington with his partner, where he continues to write and teach.

Jennifer Elise Foerster is an alumna of the Institute of American Indian Arts, received her MFA from the Vermont College of the Fine Arts, and is completing a PhD at the University of Denver. A member of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation of Oklahoma, her first book of poems, Leaving Tulsa, was published by the University of Arizona Press in 2013. Her second book, Bright Raft in the Afterweather, is forthcoming in 2018. She is the recipient of a 2017 NEA Creative Writing Fellowship, a Lannan Foundation Writing Residency Fellowship, and was a Wallace Stegner Fellow in Poetry at Stanford University. Her poems have recently appeared in Colorado Review, Eleven Eleven, The Brooklyn Rail, and Kenyon Review Online.