Interview // The Visible Woman: A Conversation With Allison Funk

by Jessica Freeman | Contributing Writer

In the seminal poem “Circling,” in her new book, The Visible Woman, Allison Funk writes, “How do we survive the dark / of the solstice, the short days of a long winter / where nothing harkens? / This little I know: the purple ash will be bare / before it buds. Nowhere / is a word I hear whispered / as the world gets colder. Also prayer.”

Allison Funk is the author of five other books of poetry and is the recipient of multiple fellowships, awards, and publications. She was educated at Ohio Wesleyan and Columbia University and is currently Professor Emerita at Southern Illinois University Edwardsville.

Her work ardently deals with womanhood, motherhood, space, and the body, and her exquisitely crafted poems often inhabit a world of wildness and weightiness. In December 2020, I was lucky enough to interview Allison. I wanted to interview Allison to ask not just about her writing process, but about how her poems traverse this central paradox of being a woman and a writer who travels inside and outside the body simultaneously. I wanted to know more about how visual art informs her writing, and what her relationship with sculpting has been.

The poems in her new book spiral and move across the landscape as she closes in on the interior of female experience and explores the body and the emotional shape of womanhood in a way that I find spellbinding, and I wanted to know more. How did she bring this book to life so well? And why has it resonated so strongly with me and with others?

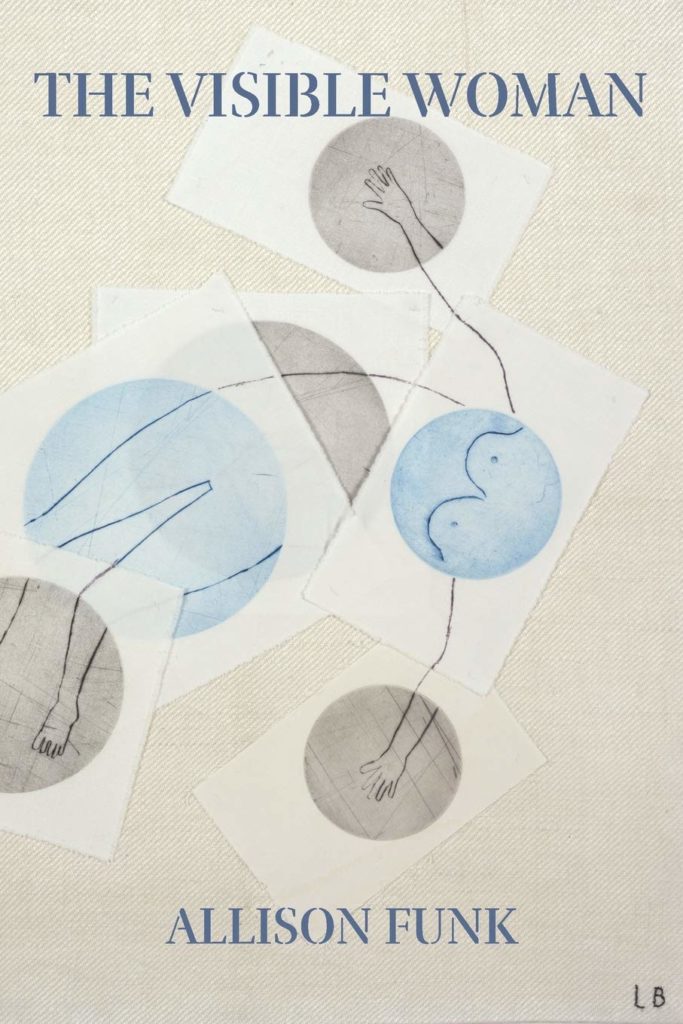

Jessica Freeman: Your newest poetry collection, The Visible Woman, has an image on the cover from the French-born artist Louise Bourgeois, and she is referenced throughout the book, both explicitly and implicitly. Can you tell us how you came to know her work, and how it has influenced your poems?

Allison Funk: I first saw her work in London at the Tate Modern Museum. I was overwhelmed by her now-famous towering spider sculpture she called “Maman.” “Mother?” I remember asking myself. I found the piece and her naming of it so provocative. A few years later, in France, I visited an unusual museum, the Louise Bourgeois Chapel, created on the site of a former convent. Again, I was surprised by how affected I was by her brave, even audacious, work. Bourgeois said that pain—psychological pain—was the business she was in, though as we all know, our physical bodies often express how we feel inside. Until she was well into her nineties, Bourgeois drew and sculpted bodies that appear contorted, fragmented, even mutilated. She channeled what hurt her into her art. I, on the other hand, am a very private person, and my poetry usually reflects my reticence. I pull back from making an “I,” a me, central.

JF: I’m struck by the idea of the “I” that you speak of in your response. Can you talk a little bit more about the connection between the self and art in these poems? For example, I notice that there is more of a focus on you and your own body in these poems than in your previous books. What changed for you in the writing of this book?

AF: I think my close attention to Bourgeois while writing this book challenged me to take more risks. She emboldened me to go back to my childhood and to write about growing up female. She challenged me to write about my experience of living in a woman’s body. I think women often disappear into the roles expected of them, becoming nearly invisible to themselves. This has certainly been true for me. In this book, I’m very deliberately using my art as a means of recognizing and representing what I’ll call a “self.”

JF: In your title poem, “The Visible Woman,” we learn that the phrase comes from an anatomical kit you were given as a young girl. Can you elaborate on the experience of receiving this model from your parents, and how it has informed your work?

AF: When I was ten, my parents gave me an educational toy, a model kit containing plastic pieces of a woman’s body. I painted the organs and started gluing the bones together, but it was a daunting task. One I never finished. Strangely enough, though, I never forgot her. The Visible Woman. Periodically I even dreamed of her. Why was she appearing to me, even fifty years later, I wondered. Finally, I tried to answer that question by writing the poems in the book I named after her.

JF: Something that stands out to me in these poems is your gift of being able to discuss the body in its minuteness, while still reaching beyond the body into the realm of what many call the unsayable. What I mean is, you create closeness and distance at once in these poems which makes the poems pop in an even more powerful manner. I’m thinking specifically about the poem “Cells” which begins with the powerful stanza, “Although self almost rhymes / with cells, I often feel I have / nothing / in common with the body / I’m in.” Can you speak to how you wrote this poem, and how you are able to encapsulate so much, and travel so far within each stanza?

AF: I titled my poem “Cells” after Louise Bourgeois’s series of enclosed chambers by the same name. Each is like a small room containing objects of significance to her, ones that suggest the most important relationships and experiences in her life. Each is a microcosm, a little world. There is a profound sense for me of an interior that, as a viewer, I’m outside of, but can peer into, like a voyeur. I wanted to do something similar in each of my short stanzas in “Cells.” I also brought to my writing an awareness of the multiple meanings of the word cell, including its being a room in a prison, sometimes a monastic space, and the biological unit belonging to all living things (“the body in its minuteness,” as you put it in your question).

JF: Your book begins with the stunning poem “Against Vanishing.” I am so moved by the diction and description in lines like, “Clavicle, sacral, I whisper, / notes I want her to savor, / but she turns and speeds away / like someone fleeing fire.” There is a lot of turning away and subtle fleeing throughout this book, and I wonder if you can tell us about the irony of this, of reaching so far inward with the body, and then moving, or turning, outward. Was this a conscious move in the poems?

AF: This is a great question, and one that’s hard to answer. As I was writing these poems I certainly became increasingly aware of my pattern. In the poem you mention, I announce my position at the start: I am “against vanishing.” I present my arguments to the invented figure I am in pursuit of in order to prove to her “how perfect she is / inside where she cannot see.” Ignoring me, however, she turns away, as you say, though I’m still calling by the end of the poem to the woman who, “dimming, then brightening,” is “the variable star I set my sights on.” This figure will make appearances, then elude me, over and over in the book. My variable star. Astronomers describe two types of them. One is “intrinsic,” a star whose luminosity changes from the inside. The “extrinsic” type can be obscured or eclipsed by another star or planet. I suppose I am both—as many people are. In my book, I write of how a person’s light can be blocked, or even put out, by others, and of how easily we dim ourselves.

JF: There have often been mother figures in your poems, but I must admit I am blown away by a new strength in some of the mothers who appear in this book. In “A Ghazal Written After Reading a Notebook Kept by Louise Bourgeois” the first line is, “A good mother needs a bad, a seamstress her thread. / Stitch a wife to mistress, imagine that thread.” Can you tell us a bit about the mother figures that appear here and how using poetic forms helped you to develop these poems? I’m interested in how formal elements create a space for you to explore the chaos that surrounds the female body and experience.

AF: You’re right that I often explore motherhood in my work. I like how you propose that formal elements create a space in which I can explore the chaos of experiences like mothering. The forms, however, create a limited space, reflecting for me, at least, the constricting nature of roles that women often assume. I tend to think of traditional forms as enclosures, but cells in which we can sing.

JF: In the book’s second section the poem “Chimera” has incredible energy and profound imagery. I think there is a beautiful wildness here, along with a tenderness that shines through. I return to the ending lines again and again, “Some days it takes all my strength to keep it / From leaving my mouth as fire.” Can you tell us a little bit more about this poem and the inspiration from which it sprung?

AF: The “it” in the lines you quote refers to the complex mix of emotions most parents experience: anger, frustration, love. A mother’s struggle for autonomy, in particular, for a life separate from her children, can be challenging. “Chimera” started for me when I discovered the medical term microchimerism, which occurs when cells from a fetus she is carrying migrate into a mother’s body, lodging in her heart, brain, or other organs, where they can last as long as she lives. I exploited this phenomenon in my poem, as well as the Greek myth of the chimera— the fire-breathing female monster with a lion’s head, a goat’s body, and a serpent’s tail.

JF: The third section of the book is almost fully comprised of self-portraits. I’m moved by the language in the titles as much as by the work within the poems and I read these poems as paintings or sculptures themselves. “Self-Portrait Inside a Labyrinth” pulls the reader through a visual landscape. You write, “And what of the moons naming the months / deer paw the earth and the corn is in silk, // when the limbs of trees are broken / by snow, or heavy with fruit? // When ice on the river lasts all day. / Meltwater’s moon.” Can you tell us about the writing of self-portraits, and what compelled you to create them?

AF: Poets are always creating self-portraits in a sense, even if they don’t name them as such. When writing mine I had the strange idea that I would try to get as close as I could to what an artist like the English painter Chantal Joffe does with paint. Forsaking vanity throughout her career, she has created realistic nude portraits of herself: first as a young woman, then a pregnant mother, and now as a woman in middle age. Although you won’t find my naked body in “Self-Portrait in the Nude,” I hope I’ve bared something of myself—even if it’s only the revelation that I prefer disappearing “into landscape, / my favorite state of undress.”

While creating a self-portrait often forces one to take a hard look at oneself, it can involve looking for yourself, too. In my poem “Diptych With a White-Tailed Doe,” I see myself reflected in the body of a deer. In others, I recognize myself in the phases of the moon or a black hole. In “Portrait Missing a Self,” it’s a starfish I come to feel a kinship with. Here, suffering “the ache / of having been, / as if I’ve become a phantom limb,” I remember “the sea star in extremis. / Which regrows / an arm. And the writer, / nearly done for, / creating a likeness/ to embody herself.” Perhaps it is ironic that with all my attention to the flesh (breasts, legs, etcetera) in this book, what I’m essentially after is something more like being than body. Something more akin to spirit.

JF: Throughout the book there is ample imagery of circling, spirals, and labyrinths. I find this unmistakably important and often present in the writing of female experience. In my own work, I often have imagery of a woman circling, and I don’t always know how it comes to me, or where it comes from. Do you have insight into why as female writers we might be drawn to this spiraling imagery, and why it is often so apparent in the physical action of a “Visible Woman”? Might this be related to notions of exposure, of being seen or unseen, or of being heard or unheard?

AF: I love that you are asking these questions. The symbol of the spiral is so rich, although I’m afraid I can only scratch the surface here. A sacred geometry exists in many religious and spiritual traditions. For Christians, the labyrinth’s twisting and turning path takes a pilgrim toward and away from the center, which is God. In my poem “Circling,” which is probably the most autobiographical poem in this book, I find myself circling a labyrinth traveled by many women nearly broken by the despair they’ve come to feel when they have children they can’t save. The question becomes for me, how can women save themselves?

Many women, worldwide, have lives infinitely harder than mine. I’m thinking of those who have been literally “disappeared,” like the girl in my poem “How We Are Silenced” who was abducted and kept for years in sexual bondage. Or the heartbreaking victims of domestic violence. Of rape. So many lives spiraling out of control.

Louise Bourgeois was obsessed with variations on the spiral in her work. For her, it represented many, often conflicting, emotions, including her struggle to control her life. She created a series of sculptures she called “Spiral Women,” which informs one of my poems. Like her, I keep returning to the form that feels very visceral to me (think of a woman’s “cycles”) and at the same time deeply mystical. In the final poem of The Visible Woman, “Late Sketch,” I follow the shapes of “the spiraling galaxies, / far-flung streamers of gas, / starburst after starburst, / tidal tails sweeping past / nebulae that resemble our own double helix.”

JF: One last question. Can you tell us anything further about your process of writing? And how it might have changed with the writing of this book?

AF: My writing of this book was influenced by my pressing concerns for the often-endangered bodies of women. It’s a subject I’ve always cared deeply about, perhaps the one closest to my heart. I’ve never explored it as single-mindedly, though, or with as much passion as I do in this book. I speak out of my experience of living in a female body, but it’s certainly not only women’s lives I care about. How can we, any of us, get past our own blinders to see and value the humanity of others? The National Library of Medicine, which created a virtual “Visible Woman,” called their larger undertaking “The Visible Human Project.” I love that. The Visible Human Project.

—

Allison Funk’s newest book is The Visible Woman from Free Verse Editions of Parlor Press (January 2021). She is the author of five previous books of poems, including Wonder Rooms (Free Verse Editions/Parlor Press, 2015); The Tumbling Box (C&R Press); The Knot Garden (Sheep Meadow Press); Living at the Epicenter (Northeastern University Press, Morse Prize Winner); and Forms of Conversion (Alice James Books). She has received a fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts, residencies at Yaddo, the MacDowell Colony, the Hawthornden Castle International Writers Retreat in Scotland, and the Dora Maar House in France, as well as awards from the Poetry Foundation and the Poetry Society of America. Her work has appeared widely in anthologies, including The Best American Poetry.

Jessica Freeman writes poetry and nonfiction, and has work published in Mississippi Review, The McNeese Review, Third Coast, Foothill Journal, UCity Review, Tinderbox, Dovecote Magazine, Flood Stage: An Anthology, River Bluff Review, and others. She is a Pushcart Prize nominee and has received an Honorable Mention from the Academy of American Poets. She is a former winner of the Joanne Hirschfield Memorial Poetry Prize and the Slattery Poetry Award from Southern Illinois University Edwardsville. Currently she teaches poetry at The Women’s Center in Carbondale, Illinois, and English at Southern Illinois University Carbondale, where she is an MFA candidate finishing her first poetry manuscript, titled Songs for the Father of Waters.