Interview // All That’s Wrapped into a Name: A Conversation with Heather Cahoon

by Shriram Sivaramakrishnan | Contributing Writer

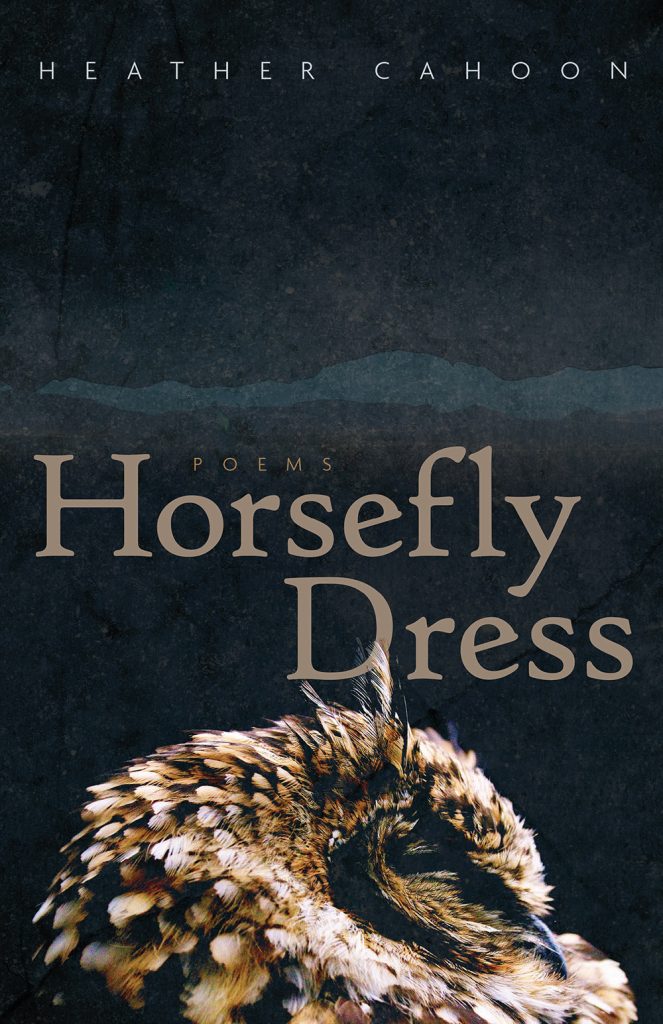

Heather Cahoon, MFA, PhD, is an Assistant Professor of Native American Studies at the University of Montana (UM) and the founding Director of UM’s American Indian Governance and Policy Institute. She is a federal Indian policy scholar whose academic background and research interests include tribal sovereignty and self-governing rights and related issues. In addition to her policy interests, Heather is also an award-winning poet and the author of Horsefly Dress. In 2015, she was named UM’s first Elouise Cobell Land and Culture Scholar, a title reserved for faculty who are continuing Elouise Cobell’s legacy of working for justice and equity for American Indians and tribal communities. Heather is from the Flathead Reservation where she is a member of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes. This interview happened over a series of emails late in 2020, a year like no other year. And so, as the light decayed into a pastiche, and the world woke from its tenured slumber, we typed and typed and typed. I thank Heather Cahoon for the symphony of clicks.

Shriram Sivaramakrishnan: I would like to kickstart our discussion with the first thing that caught my attention when I was reading your book: the use of Salish words. In your recent reading for The University of Arizona Press, you spoke about weaving Salish into your poems as an act of reclaiming, among other things, the land. It reminded me of a quote by Maurice Merleau-Ponty (I came across it while reading Maggie Nelson’s Bluets), “words do not look like the things they designate.” In the same reading, you also mentioned that you do not speak Salish. Given that your poems are firmly situated in the realities of the land, its people, and their tradition, how does language inform your creative practice?

Heather Cahoon: My poems are definitely rooted in place and reflective of my personal relationships with the landscape, people, flora, and fauna where I live. In terms of how language, specifically my use of Salish, informs my creative practice, I would start by noting that the level of Salish that appears in Horsefly Dress roughly mirrors my speaking ability. Growing up, everyone learns a handful of words and in college I took Salish from one of our elders but I certainly never came close to being fluent. As a result, my decision to include Salish in my poems was very intentional and serves a sort of dual purpose. On a basic level it connects me to my community and reaffirms those ties but it also calls attention, at least momentarily, to American Indians generally and, by extension, the settler colonial history of America. This is why I say that the use of Salish is an act of reclaiming space, not only as a presence on the physical lands where Salish-speaking people have been living for thousands of years, but the non-physical landscapes as well, including the broader American psyche and the mainstream narratives that have largely omitted tribal people.

SS: I love the idea that language can help one reclaim a place in the psyche of the zeitgeist. It is reflected in the ritualistic nature of your usage of Salish words. By this I mean, it resembles an act of invocation, as in “From Trees” where the prayers are let out as embodied cries. I am particularly fascinated by your relationship, insofar as the poems are concerned, with names (of places and people). For instance, in “Horsefly Dress,” the speaker hears the name Č̓atnaɫqs along a stretch of river. The poem ends with a warning, “Brace for all that’s wrapped into a name.” In “Mést m’/Lʔéw” for instance, the speaker refers to a sister who was named after their grandmother. I can’t help but read the act of naming in your poetry as an unveiling (and a possible reclaiming) of history. At the heart of this poem is the question, “Is it possible [. . .] we own our stories / in a way / that feels like trust?” How would you define your relationship to names and the naming?

HC: There are of course different names for the same things or places and different ways of knowing these things and places. For example, everything in the Americas had already been named way before colonists, conquistadors, and settlers arrived and these aboriginal names tell a very different story of people and place than is generally reflected in the mainstream today. Thus, as you note, revealing the Salish names is a way of unveiling or reclaiming history; however, it can also be a way of reclaiming the future. Wrapped into Salish place names and words is a distinct worldview that, among many things, contains a distinct understanding of the role and purpose of human suffering, which is a stronger point I hoped to get across in Horsefly Dress.

Not to sound overly reductionist, but as a church-going child I understood suffering to be a very negative thing, that all suffering was warranted on some level, and that it was the deserved consequence of committing a sin or wrong-doing that had invoked the wrath of God. I also learned that one should try to and could successfully avoid suffering by avoiding its triggers. But what about the deep suffering that seems random and completely unwarranted, as in the case of a child born into the horrors of war or the person who is struck with a life-threatening illness or the widespread death and loss that stems from natural disasters? Following some very early and formative encounters with this type of suffering, which I write about in several poems, I struggled to identify or understand the underlying triggers—I couldn’t ever answer the question of why these things had happened.

Later on, as a young adult I was introduced to a very different philosophy that was not focused on the “why” of suffering or on its avoidance. From tribal spiritual leaders and from studying our oral traditions I learned that suffering was something we should step up to meet head-on and with respect for the opportunities of transformation that come with it—and not just personal transformation (like building strength of character), but the possibility of effecting a much broader change in reality, in future events and circumstances. Because suffering was seen as having widespread transformative powers it was not seen as something to be avoided; it was perceived to be an integral part of the sacred and people actively sought out or self-inflicted ritual or ceremonial suffering specifically to access its transformative powers.

This was a very different view than I had previously been exposed to and it really resonated with me. In Horsefly Dress I wanted to share these Séliš and Qĺispé insights into what is a very common, universal experience. Settler society has worked hard to stamp out these and other Indigenous beliefs but I think they are worth knowing and worth sharing with a broader audience.

SS: I love the idea that Salish names enwrap a worldview that contains a distinct understanding of human suffering. And in doing so, I am tempted to believe, they also enwrap a world. For in your poems, names seem to represent the essence of things they mythologize. In Geography of Coyote, the sons of Coyote and Mole are named with such functional monikers as “He Knows as He Lays His Head Down,” “Lays Down Straight Under a Tree or Log,” etc. These challenge the nominal nature of naming that we are exposed to. On the one hand, it can be argued that such aesthetics of naming will lend the underlying language to translation. But the name of the fourth son, Yelcnetpawastqn, indicates otherwise. It is a “name unwilling/ to be translated into English.” An act of defiance. Its presence in the middle of a sea of English words represents the “complex pedagogy of contradictions,” something which is important for Snč̇ĺép to demonstrate the “right ways of living.” These, I presume, will help ground the people in their tradition, the way the act finds its roots in the Salish nč̇ĺpscut.

But in sharing the specificity of Séliš and Qĺispé insights about suffering, which you rightly call as a common universal experience, you have beautifully situated the poems in a bigger arena, for a wider audience. I am invested in the way you have used frames of references from/in nature, to capture the suffering. In “Łcˇícˇšeʔ” for instance, a wood-warbler has “her calls smothered / inside / her smoke-gray chamber of throat, while her eyes / sense but can’t see / at the center of night movements / misfire / misreads the body / responds on its own.” Reading it, I can’t help but think if writing itself is a ritual— perhaps as urgent as one can endeavor to—that one engages in to capture and represent human suffering. Considered this way, suffering becomes akin to accessing memories, in that both depend on our capacity to utilize language. If this is true, poets and writers are essential practitioners, shaman-like, in their communities. How do you see your relationship with suffering as a poet?

HC: I hesitate a bit to put poets and writers on par with medicine people but I do agree that they serve an essential function in their communities. There is no doubt that throughout history, across multiple cultures, poets (and writers, artists, performers and musicians) have engaged the most timeless of existential questions and their work has helped guide multiple generations through difficult situations. Although I was not thinking about this when I wrote Horsefly Dress, I did choose to focus on the theme of suffering because of my own struggles to make sense of or to process the stubborn grief I felt about a variety of situations and the likelihood that there were others within and outside of my community who felt similarly. I wanted to offer up what I felt were some very meaningful insights about reframing the experience of suffering that I had learned from some of our elders and from searching for information about Horsefly Dress in our oral traditions.

SS: I see what you mean about the role of poets. They may not be on par with medicine people but they remain the apothecaries of the collective consciousness, at least the historical continuity of traditions the world around. I say this because you have also played the role of a historian, (re)searching for information on the subject of suffering, stories on transformations, and about Horsefly Dress, from the elders. These were, as you have mentioned, traditionally passed down generations in the oral form. And while orality determines the soundscape(s) of storytelling, I believe it is the act of writing that solidifies them, providing them with a definite form.

In the same reading, you touched upon the vitality of dreams (and dreaming) to your writing process. To a question about “Nunxwé,” you spoke about arriving at its exploding form when you scribbled the poem on paper in blue ink. I am intrigued by that connection. The color blue (and you meditate on it later in the book) signifies water which, like oral stories, does not have a definite form, except for a sound structure. You mentioned in the same reading that your dreams, at least most of them, “often had an element of water in them.” And yet, all of the “dream poems” (such as “The Salish Root Word for Water”) in Horsefly Dress are formally represented as prosaic blocks. In the same poem, you expound on the Salish root word for water: séwɫkw. One of its many meanings is “to make a plea to be worthy.” I can’t help but think if that has been your task all along, in capturing these stories. Do you agree with it? And if yes, what do you think is at stake here?

HC: Yes, I would agree that this has been my primary task—to, as I write in the poem “Render,” figure out how to become worthy of my most embattled moments. By this, I mean figure out a way to execute the difficult task of exacting a paradigm shift within my own sub/consciousness, of going from the perception that I had been subjected to certain events that caused me undue suffering to a place where I saw these instances as opportunities for the kind of transformation I mentioned earlier. This latter perception can be very empowering and can, I think, help prevent the development of some of the most troubling outcomes associated with trauma, which are often triggered by an overwhelming sense of helplessness. And considering how dominating, disruptive, and discouraging the psychological and physical manifestations of trauma can be, I think that it is accurate to say that one’s future can be at stake, though this is obviously edging into an area of conversation more appropriately had between an individual and their mental health care provider. But on a basic and very much non-clinical level, with Horsefly Dress I wanted to add another perspective, based on my own experience, to nuance the existing dialogue on this topic. I also wanted to reflect back to my community the validity and beauty of the Séliš and Qĺispé way of engaging with this unavoidable aspect of life.

SS: To engage with suffering, rather than avoid it, to pave the way for a dialog. Yes. That is the need of the hour. The poems in Horsefly Dress capture the sense of helplessness, which you just mentioned, in the face of suffering. I am struck by the epigraph in the poem “Escape Routes,” “Each person has to create their own escape routes from the situations they cannot tolerate.” One way to understand it is to place it in the context of our conversation. The poem tonally moves across different registers. It juxtaposes the wonderment the speaker’s sister experiences—in “the certainty of hooves connecting with the earth,” at the rhythmic movement of the horse’s belly, which leaves her with a “feeling of complete utter presence, the kind that insists you are powerful”—with what I can only describe as the wind violating the very existence, of a life. This incident leaves the speaker with a sense of reckoning, an alarming mo(nu)ment of clarity. The speaker realizes that our body, itself an embodiment of time, is also a sanctuary to our past (and past traumas). I wonder if this is the same place that the speaker calls “the unknown” towards the end of the poem, the place where “it’s okay to admit / we are powerless.” What do you think is the role of the body in the Séliš and Qĺispé way of engaging with suffering as this unavoidable aspect of life?

HC: While I have some thoughts on this they are not informed exclusively by Séliš and Qĺispé philosophical traditions, nor am I in a position to speak so broadly on behalf of the entire Salish and Kalispel tribes. Although I was born and raised on my reservation, I was not born into or raised primarily within the Séliš and Qĺispé worldview—and, due largely to the acculturation efforts I mentioned earlier, neither were the majority of my fellow tribal members, which is partly why I messaged the poems as I did. I wanted to highlight—for anyone, but especially for my own community—what I found to be incredibly helpful ideas about reframing our experiences of suffering based on what I had learned from elders and from studying our oral traditions.

To provide some context on the real-life implications of the situation and my underlying motivation, while I was working on Horsefly Dress there was a series of deaths on our reservation where twenty people (several of whom were youths) died by suicide within a year’s time. This is an enormous number for such a small community and there were lots of conversations about how to address this. Under these circumstances, I was able to interview a handful of elders on Séliš and Qĺispé ideas around suffering. A lot of what they said is reflected throughout Horsefly Dress and has already been touched upon in this interview, with perhaps the exception of rebirth. One of the elders talked about the importance of recognizing that life is a series of rebirths and that we are constantly being reborn. In my studies, I came across a statement related to this that said that physical death becomes unnecessary when we understand or are able to affect a metaphorical death, which is to be reborn into a new state of consciousness, which itself is to become a new or different person.

This idea of rebirth is very much present in our stories and is a theme on which I wanted to end Horsefly Dress. Toward the end of my book, in the poem “Meta,” I write about this kind of transformation seen in the stories, especially with Coyote, who “is a man / is an animal is a teacher repeatedly killed and reborn. / He suffers an endless series of deaths, some metaphorical some / metaphysical, each one metamorphic.”

SS: Reframing seems to be the central tenet of Horsefly Dress. One poem that I keep going back to in this regard is “Meditations on Blue.” I trust the speaker when she says “we categorize to create meaning therefore / it is possible / to change meaning by recategorizing.” And when she ponders “if crisis truly carries opportunity what of the recursive nature / of loss where is the exit from ruin,” I also share her concerns. I can’t help but think if it was born out of the speaker’s tryst in reconciling with the multiple deaths she has witnessed so far. I was tempted to read it in the light of what you shared from “Meta,” the metamorphic nature of death(s) as experienced by Coyote, but I found a stronger affinity with the idea that you just mentioned: “physical death becomes unnecessary when we understand or are able to affect a metaphorical death.” I wonder if it means that physical death can be avoided? How do you see the word unnecessary (and its possible ramifications) in this context? In other words, if there is “the exit from ruin”?

HC: There is always an exit from ruin but the form it takes depends a lot on us and, as the elders said, how we view and engage with these situations. As for whether physical death can be avoided, ultimately it cannot, as evidenced by the fact that at some point eventually each of us will die. This type of death constitutes the end of a particular physical experience or existence (though it is also perceived to be part of another kind of rebirth wherein one continues to exist but in a different form). Conversely, metaphorical death is representative death where some aspect of one’s self ceases to exist. As I noted earlier, the “rebirth” associated with this is a fundamental shift in consciousness that leads us to a new state of being. In the context of the last question, I see the word “unnecessary” in the phrase physical death becomes unnecessary when we understand or are able to affect a metaphorical death, as meaning that if we truly understand that actual, consequential transformations (changes in oneself as well as in future events and circumstances) can be achieved through metaphorical means, it offers us an alternative to enacting physical death. I don’t mean to suggest, however, that this is all there is to dealing with intense pain and suffering but I think it is an important part of that—if it wasn’t, these ideas wouldn’t appear so centrally in our oral traditions.

SS: I truly love the idea you expose here, that consequential transformations achieved through metaphorical means can offer us an alternative to enacting physical death. I am, of course, referring to “Death as a Lens” where one such transformation occurs through the act of “seeing the innermost contents” of a dead grouse. The poem ends with “the sharpest knowing is with one’s eyes,” which, in the light of our conversation, makes me consider if you arrived at this moment of transformation by witnessing the death of the Other. The “you” I am referring to is the stillness between the speaker, the poet and the person. This “you” is, I believe, the only way for me, both as a reader and as an outsider, to access but also appreciate, the Coyote, and more importantly, the Horsefly Dress. I see the Horsefly Dress as a mosaic of your life experiences. How would you define “your” relationship to the Horsefly Dress? In “Rilke, Screech Owl, and Night Loons,” for instance, when the “you” says “Horsefly Dress tries to believe / there are no casualties,” I try to believe it, too, even though I am aware of the fact that believing and trying to believe are two different things.

HC: I really like how you’ve phrased the action in “Death as a Lens,” the process of arriving at the stillness between the speaker, the poet and the person. I will say that I am generally the speaker of these poems and I agree with your observation that Horsefly Dress is a mosaic of my life experiences where the “my” extends beyond me personally to include my family and larger community. In terms of my relationship with Horsefly Dress (the individual), I identify with her on many levels and see reflections of her in myself to the degree that I sometimes integrate our identities in certain poems, like in “Rilke, Screech Owl and Night Loons.” I think something that helped to further solidify my identification with her was when the director of our culture committee told me that Horsefly Dress—and Snč̇ĺép, Pulia, and all their sons, etc.—were and are real and that they live on in each of us. One of the ways they do this is by continuing to influence our thoughts and behaviors.

SS: Which is apparent in your work. And perhaps no other poem reminds me of this more than “WASP.” It is no wonder that the poem, especially the way you have enjambed the lines, carries political overtones. For instance, “Coyote and Spider, / Muskrat and Raven refuse / to allow their transformative work / in this place to have been in vain.” Further along, the speaker asserts “Open your mouths and let out your breath, / let it form the ideas whose first step toward / realization is articulation.” I would like to think of the director’s comment as a form of articulation, in that it gears you towards solidifying your identity. But if that were to be true, how should I make peace with “The Hawk Who Wears an Owl’s Face.” Did the hawk appropriate the identity or was it forced to wear one?

HC: This is a great question; there is always so much to unpack when it comes to identity. On the surface, the northern harrier was just a bird I saw perched in a tree while I was hiking. At first glance, I mistook it for an owl—a second later, it flew from the tree and glided directly over my head and I realized that it was actually a hawk. Later, I learned that it’s the only hawk who hunts by sound as well as sight, hence its owl-like, disc-shaped face that funnels sound to its ears. In this sense, to answer your question, it was I who forced the owl’s identity upon the hawk. My intended message of that poem though, and of the last several poems in the collection, is about things not being what they might seem on the surface—the hawk, the wild orchids, the woman in my dream—and that the situations we find most challenging are greatly impacted by the lens through which we are experiencing them, which depends on how we identify or label them.

Being asked to dig deeper into the possible subtext of the hawk poem and “WASP” (which puts down settler colonialism and uplifts Indigeneity) is interesting in the context you’ve presented about identity. There are so many possible directions I could go with my response, but I’ll take this opportunity to say a little bit more about the construction of my own identity since it is something people might be curious about. In a recent interview I was asked about how I identify myself, which is as a member of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes. This is a political status that some say is more accurately defined as citizenship and it’s grounded in tribal nation sovereignty and political autonomy. If I’m asked to identify my specific tribal affiliation I generally say Kalispel/Upper Kalispel (or Pend d’ Oreille, as we were called in the past) because that is my strongest cultural affiliation. Beyond this, it gets more complicated. Like me, both of my parents were born and raised on our reservation and both are tribal members. My father’s family is mostly Upper Kalispel but he is also Nez Perce and Spokane. My mother’s tribal family is Kootenai and Chippewa but most of her ancestors came here from western Europe. Like so many people in the U.S. today, I am quite a mix of things, many of which I have no meaningful connection to.

Given all of these realities, identifying as a member of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes feels more accurate than listing out my five different tribal affiliations or tracking back to Europe. That said, I have considered the situation that this identification creates wherein my tribal membership can shield me from having to stand with settler society when it comes to owning the atrocities that were collectively perpetrated by settlers against Natives, which positioned settlers and their descendants in a place of collective privilege within American settler colonial social structure. I have written about this before and was talking about it a few years ago with one of the women I used to sweat with. Because of her position in our community and the status of her extended family as tribal cultural and spiritual leaders, what she said has stuck with me and that is, that my European ancestry gives me permission to pass through the door into the mainstream—permission that she does not have based on her lack of “whiteness”—and that my tribal ancestry and connections to my home community give me permission to pass back through the door. She said that this ability to come and go into different physical and political spaces as I please is a form of privilege that comes with its own kind of responsibilities related to representation. Thus, as I gain ever-increasing access to the mainstream and opportunities to engage the dominant narrative, I will always bring pieces of home with me.

SS: That makes sense. Your response made me think about “identity.” Etymologically, the word has its roots in Latin idem to mean “same.” To possess an identity is to portray the quality of sameness. But without a frame of reference to initiate a comparison, one cannot possibly fathom what must it be identical to? Then again, maybe it is not important. For we are, as you have rightly pointed out, “a mix of things, many of which [we] have no meaningful connection to.” The stories we are provided with, and the ones we tell ourselves (and others), ground us in what we call “realities,” which provide us with frames of references, so that we may build connections that mean something to us. I mean, aren’t the socio-cultural and political spaces that you have mentioned, narrative structures? All of this is to say that I agree with your point about the privilege, and the responsibility you must bear when entering these structures. But I ask myself, what is the point of carrying the “pieces of home”? Do you see yourself consecrating them in the spaces you enter? What is your way forward from here?

HC: I love how you’ve described the intersections of identity and stories and the “realities” they create, and I absolutely agree that our socio-cultural and political spaces are just narrative structures. As for carrying pieces of home with me into these spaces, my point is to try to affect meaningful changes in the lives of my own and other tribal communities and to help perpetuate the stories and deep knowledge of place that can benefit all of society. This is ambitious, I know. As I described in my response to your first question about my use of Salish in Horsefly Dress, my poetry does this in subtle ways, but I think my work as a policy scholar and analyst probably has a much greater potential when it comes to producing measurable impacts. I often refer to the world of public policy as the world of human constructs, and I think that public policy creation is one of the most intimate of interactions with the narrative structures a society has built and maintains. Although I view the natural world as the real world—as a reflection of the innate structures and processes undergirding the internal workings of the universe and reality—I see working to influence public policy at various levels as the chance to influence the overarching narrative structures upholding our socio-cultural and political realities. As we have seen, these narrative structures morph over time as different stories or voices get heard. So, my way forward from here is to continue my current path as both a poet and policy scholar.

SS: Poetry and public policy, two constructs more humane than anything I can imagine, one interested with the individual psyche and the other with the collective identity, yet both share an obsession with regulating, if I may, the politics of personal space(s) . . . I can’t think of a better way to end this amazing conversation, Heather, even though I hope the questions we have raised, and the themes we have touched upon, will continue to resonate with those to whom Horsefly Dress truly belongs. And while I want to sing more praises in calling it a day, it will only be fitting if you have the final say . . .

HC: Thank you, Shriram, for your thought-provoking questions and the chance to discuss my work in such depth. I echo your hope that our conversation and the ideas in Horsefly Dress will continue to resonate with people.

—

Shriram Sivaramakrishnan is an alumnus of the Seamus Heaney Centre for Poetry and a second-year M.F.A. student at Boise State University. His poems have appeared in DIAGRAM. His debut pamphlet, Let the Light In, was published by Ghost City Press in June 2018. He tweets at @shriiram.