Interview // “Always a Condition of Urgency”: A Conversation with Cleopatra Mathis

by Rachel Richardson | Contributing Writer

I met Cleopatra Mathis in my second year at Dartmouth College, where she was the Frederick Sessions Beebe Professor of Writing, in the late 90s. She taught the first dedicated poetry class I took, which profoundly focused my sense of the possibility of language and my own devotion to it. I was mentored by her for the next three years, during which time I learned that her daughter was the same age I was, that she and my father had grown up 50 miles apart in small cities in north Louisiana and knew each other’s cousins, and that she didn’t think legal pads were a formal enough place to draft poems. (I still use them; it’s one of the only places where I haven’t come around to her advice.)

I have followed her life and writing for the past twenty years, concerned at times that I was emulating her, and at other times trying to rebel. But her influence has endured in my writing, and my gratitude for her teaching and the model of her life has only deepened.

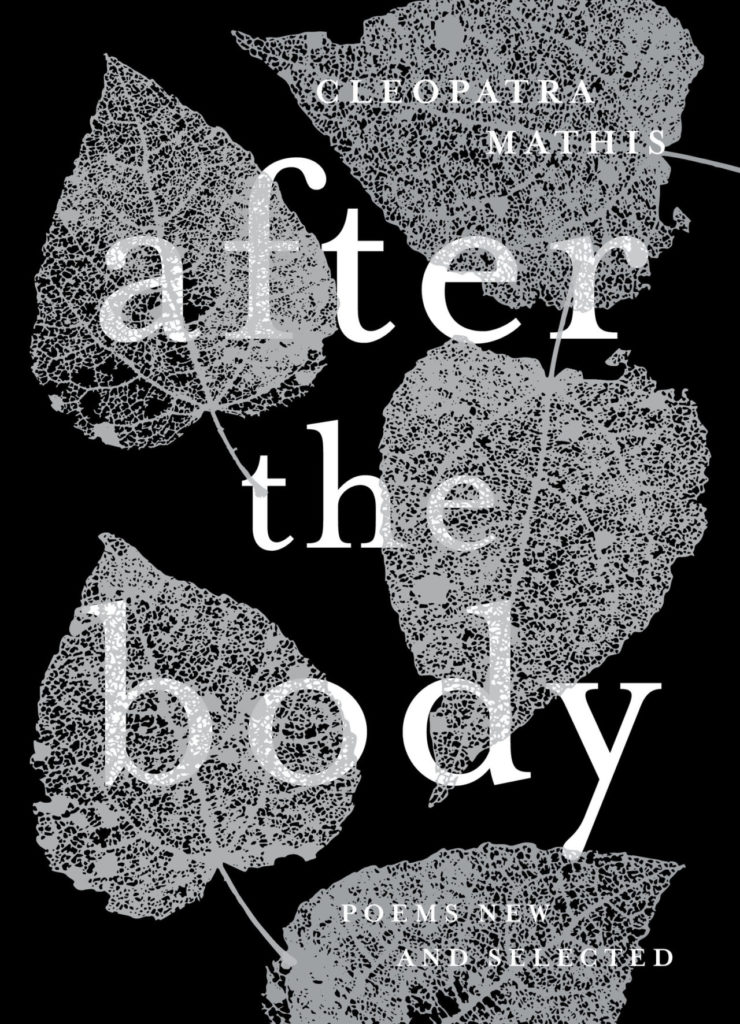

We conducted this conversation by phone in spring 2021, just after the publication of her After the Body: New and Selected Poems, and in celebration of her retirement from Dartmouth College and the Creative Writing Program she founded there. We discussed her own mentors, being a teacher and parent, the use and rejection of metaphor, and writing about whiteness, insects, and the body’s failures.

Rachel Richardson: You were my first teacher, and I have of course been shaped by your mentorship, but in reading After the Body, your new and selected poems, I have been realizing just how much I have traced my own life onto your work. Your first book came out the year your daughter was born, which is also when my first book arrived. Many of your motherhood poems feel like a map for me, and reveal to me things I was doing subconsciously. So now I’m looking at your fourth book—which must have been written in your early 40s—as a guide to my future.

Cleopatra Mathis: Yes, it’s interesting how poems can speak to certain stages of our lives. Certain poets (Yeats, Hopkins, Auden, Bishop, Szymborska, to name a few), have a lot more to say to me now that I’m an older person. And as a fairly autobiographical poet, I think that you can map the major events of my life from book to book. So I’m not surprised that you can see your own life changes mirrored in my work.

RR: One of the things that I find interesting, having read many of these books as they were written, is what it was like for you to put them together into a selected work. In that process of looking back at your whole arc, were there things that came as surprises to you in the way your poetry developed?

CM: Putting the book together was overwhelming because I realized that limiting myself to 250 pages or so meant leaving out a lot of poems. Rather than trying to choose all the best poems, I wanted a unified book, one that had some of the same thematic qualities and sense of progression as a single volume. I struggled with what to include until I had the title, which gave me a real purchase on how to proceed. I liked After the Body because of the various ways in which the phrase could be interpreted. In my first two books, my approach was elegiac: I was mourning specific bodies. The body versus the spirit developed slowly, the sense that the body could be failed by others, that the body itself would fail, and it would be my own body that would finally refuse me. So that play on the title became my approach. I did try for variation in selecting poems, especially if they were similar in style or intent. I found myself wishing that there was more levity in my work, more perspective. I know I’m an obsessive poet . . . but I do have a much better sense of humor than the poems would suggest! Also, for one reason or another, the friends I usually rely on weren’t available to respond to drafts or to give advice about my choices. I think this was the first time I felt I was working completely alone in putting a book together. It probably seems strange that someone my age would still long for a mentor, but I don’t think you ever lose that need for a response from an ideal reader, or stop missing those people who have influenced your work and made a difference in the poet you’ve become. Putting this book together was hard, but now I think it was important to feel that isolation rather than listening to other people. Having to step away and evaluate my work from some distance made me see it differently.

RR: Did you find that in your newer work things have fallen away that you used to rely on or care about?

CM: I was surprised to realize that the image is not so important to me anymore. When I went back to my old work, particularly that written in my 20’s, I saw a lot of impressive imaginative leaps and my facility with image and metaphor. But I also saw some language that didn’t matter, that slowed down the poem and made me (and I assume my reader) impatient. I could also hear my teachers’ objections much more clearly than I did at the time. As a young poet, I was mostly in love with image, not the crafting of a poem, with attention to progression and meaning. The image is what first drew me to poetry. William Meredith called me on this at Bread Loaf, and I still remember Stan Plumly’s admonishment: “The image has no voice!” But as my work matured, the significance of poetry took on a different meaning. Writing has always been a condition of urgency for me, a way of surviving life events; I think finding language to illuminate the emotional experience was central. Certainly, the new poems do not rely on anything like that. They’re much more straightforward, much more intent on communicating a state of being. I still want the invention—but like a jazz musician’s riff, a tune, variations on a phrase that enhance meaning, not distract from it. In those first couple of books particularly, I was not thinking so much about what my reader needed: an attention to craft rather than evocative language. My concern with the more utilitarian sense of the language, its communication, probably has to do with being older. I don’t want to waste my time or the reader’s time. The bad part for me now is that I keep cutting and the poems shrink! You probably noticed that.

RR: I did! But I wouldn’t describe it negatively—they feel whittled and essential.

CM: I found that the poems were short and many of their subjects repetitive. The nature of the illnesses (particularly Parkinson’s) I was struggling with was obsessive and seemed to be non-ending, and their questions not fully answered in a single poem. In terms of the language itself, which is a different concern, I needed to speak more urgently and to the point. Although saying something in an interesting way was still as important as it’s ever been, I thought more in terms of the music of the poem. I was thinking about what I was trying to get at in the tone and its variations, and how they affected the movement forward of the poem. The poem’s sound and progression were dependent on an underlying music—it’s almost like a beat I hear below the surface of the poem once I’m deeply involved with the writing. But my interest in metaphor is more in service to the poem.

RR: It seemed to me that there were many more metaphors in your past work, and more developed images, and now there’s this sort of essentialized poem of observation. When images appear, they are more spare and not necessarily metaphorical. There’s direct observation or memory or anecdote instead. It feels like there’s no structural removal, like “here is my poetic device;” instead, what is here feels integral to your life and thinking.

CM: That’s what I wanted, I think, but there was no conscious decision. Personally, I felt stripped away by the disease, and only wanted to present what is. I think I began to distrust any kind of adornment in the way of image because I saw it finally as being sentimental. And “like” itself became an impossibility; the illnesses were like nothing I knew or expected. At first, I even tried to resist writing about them. I was afraid that Parkinson’s would be front and center, that my personal suffering would take over the poem. The poems are a response to illness and a trigger, but I don’t want any confessional message to determine the poem. Obviously the reader is going to have sympathy or compassion for someone going through a lot of pain, but the poem itself does not exist for that purpose.

RR: I’d like to move to your relationship with the natural world. It’s a trove of images in your books. How did you learn the things that you know about egrets and the western conifer seed bug and all of the other animals that populate your poems? You’ve talked about the importance of nature in your work, but what is the method? What is your outdoor practice that brought you in such close contact with the world?

CM: Observation is the key. I was a lonely child who spent hours outdoors, where I was always more comfortable. As far back as I remember I have been a person who identifies animals as having the same motivation and feelings that humans have. I even anthropomorphize plants. I think that if I had not been a teacher, I probably would have been a naturalist. I love every aspect of the natural world, even in the iciest winter. So when I see a bird outside the window at the feeder I want to know exactly what that bird’s doing, why he’s doing it; I am not thinking about writing a poem. I am no stranger to bird books, plant books, certain naturalists’ writing. I cannot bear to see suffering, and most times have to avoid graphic photographs. When a poem arises out of some event, I tend to focus on a lot of information as I’m revising. Sometimes I find my conclusions are all wrong, sometimes I find wonderful things. I do research because I don’t want to present something that’s untrue in a poem. If I use an animal, a bird, a plant, weed, whatever, I am preoccupied much of the time with accuracy. Sometimes it’s the act of reading or seeing that prompts the poem, not the other way around.

Nature is full of drama! A forlorn bluebird can occupy me for days—her nesting habits and travels from the same tree to tree, looking for her mate, who I realize has disappeared. Days pass, and she too finally disappears and when we realize it and clear the box of its four little blue eggs, I am full of speculation about what has happened. How could a poem not come out of that? If you’re not into nature and you look out and see a bluebird, you’re only going to see a bird. But if you’re watching really closely for several days and you notice everything about that bird and what it’s doing, you’ll write about it differently. It won’t seem like a pasted-on metaphor; it becomes intrinsic to your own experience because you track it the same way you do your own experience.

The western conifer seed bug poem is a good example. I discovered that a little bug I kept seeing in my house in the wintertime just needed a place to remain semi-dormant through the coldest months. I don’t like to kill anything, so if I found one I would take it outside. Finally, it happened that a woman wrote about the western conifer seed bug in the local paper, wondering what it was doing in our houses. When I looked it up, I was devastated that I had been putting them outside because I learned they come in needing shelter and they just hide out. They go into a kind of animal fugue state—no mess—and they’re totally harmless. Then when it’s warm enough in Spring, they somehow figure out a way to get back outside and they help the conifers open their seed pods. At the same time this occurred, I was going through a divorce and was totally fixed on how I had done everything in the marriage to keep it safe, tried to look after every single thing, and for what? I’m brushing my teeth and suddenly there he is, dead on the counter.

If anything, I’m even more in that mode of discovery in my natural surroundings because I have more time now. So much of what I see and read seems to resonate with events in my life. Whatever I discover seems to have some parallel, or corresponds to life events without my doing anything more than taking notice or being prompted to go look something up.

RR: It feels like the difference between observing to gain understanding of yourself, as opposed to knowing what you want to say and then employing the image that will serve to support a point.

CM: Right. I also love being wrong when I look these things up. They can change my poems by changing what I understand about what happened to me or reveal some other aspect of my experience. To write convincingly is so integral to the creative process that you need to be in a state of flux when you write. You don’t want to close down the poem before you have a chance to know what it can do.

RR: Would you like to talk about how you write and have written about race, your family’s story in Louisiana, and your own identity there? I went back to those poems and was thinking about how you approached that subject early in your work and then came back to it later in White Sea. What did you feel was the challenge and obligation to that kind of testimony in the 70’s when you were first writing those poems? And how do you update those kinds of thoughts as the conversation on race changes?

CM: A lot of what I’ve been trying to do lately has to do with that subject, especially in terms of my mother. My mother is behind those new poems in many ways—she’s just not completely out yet. My early poems bypassed her completely, though she was actually pivotal for me in terms of my attitude toward race. Instead, the poems eulogized people of color who I loved in my childhood, who I had taken for granted. Writing about race has been problematic for me partly because my son has been doing social justice work since he was in college; he’s incredibly sensitive to any sense of appropriation. He is my hardest critic when I try to write about how I grew up in north Louisiana. I’m trying to place my experience and the kind of racial temperature and reality that I grew up in, as well as the complication of my own blindness and race blindness. All that is complicated by the Greek issue, of being different from the white southerners in the town and therefore more aligned with the Black community. And yet when I say that, my son practically goes through the roof. He says I cannot possibly know what it’s like to be Black, and it’s offensive when I talk as if I can. So that’s been very hard for me to reconcile.

I don’t want to offend anybody of color, but I do have something to say. To further complicate issues, when I did 23 and Me, I found out that there is northern and western African ancestry in my chart. I’ve been told all my life that my grandmother on my father’s side was Native American. I barely knew my father, who died years ago, and I am not in touch with anybody in my father’s family; I don’t even have names or addresses. Yet I have good reason to believe that my father’s mother was Black or possibly bi-racial. There was no Native American in my chart. So how do I talk about this? How do I find my way into this material? How do I shape it? Here I am with a grandmother who most likely passed as white, and my father’s family is from a little place called Harrisonburg, so tiny it doesn’t appear on most maps. I think it’s across the river from Natchez, Mississippi, which was the biggest slave-owning area in the whole country.

RR: I can see why it’s disorienting, but it also sounds like a very common story of the euphemisms and outright lies that so many families told, especially in the South, about their lineages to create a mythology of a simpler kind of whiteness and racial purity. It’s hard to talk about because of the ways that we can move through the world as white people, and how we have been able to ignore or not physically represent those other heritages even if they’re in us. We don’t pay for them in terms of the way that we’re seen in the world, and so the question is: how can we claim them, and should we?

You’ve returned to portraying some of the people who worked for your family in White Sea (2005), published 26 years after your first book, Aerial View of Louisiana. I remember the poem “Cane” really striking me when it appeared—its subject is Chester, a Black man who was close to your mother. How do you see that poem and the others you’re writing now? Are you intentionally updating these eulogies and odes you had written to the Black members of your community in your earlier work?

CM: Rather than eulogizing the Black families I grew up with, I’m preoccupied with their intimate role in my family’s life. Genie Belle was much more than the head cook at the cafe: she was my mother’s friend. When my mother needed help as a single mother to three small children, it was often Chester, Genie Belle’s husband, who came to do those favors. Because close race-relations were prohibited at that time, her relationships with many Black people in town were secret, or at least not spoken of. When Black folks came to our house, they came to leave vegetables and fruit on the porch at night, never in the light of day. My mother regularly drove out to their place in the country, where Chester had a truck farm (hence the poem “Cane”). I took for granted that they were always there, taking care of me while my mother worked seven days a week as a waitress, but kept invisible. Later as a “white” girl, I criticized my mother, mocked her language for being like theirs, and ignored her friendships in the Black community as much as I could. She also fought with her family about this, particularly one of her brothers.

Reading about white privilege now, I see that this is exactly where prejudice comes from: the implicit, taken-for-granted superiority that whites silently assume. This acquiescent, passed-on role troubled me, but I went along with it even though I loved those women who took care of me. I paid no attention to my guilt: it was just the way things were. In my first two books, I could only admit and praise their crucial roles in my life. In later poems, I began to understand my complicit participation in a racist culture. Now I am more interested in exploring the effect of our relationships with so many Black families—how my mother rebelled against it in the small ways she could. In terms of craft, I suppose it is a change of tone—an uncertainty and willingness to acknowledge fault. I know these poems will be freer in form and ask more questions than my previous poems on the subject did.

RR: I really admire that effort. The deepening investigation is so rich, and feels really important to do, on a personal as well as poetic level. The other part of your comment, on your children, makes me interested in what my children will have to say about my work when they grow up, how they will judge what I’ve said about who I am and the people we come from. How do your children feel about the poems about them, their childhood, and your parenting?

CM: My son loves those poems—when I was putting the selected together he had favorites that he didn’t want me to leave out. He’s not troubled by my ambivalence toward being a mother. He always wants to see what I’m working on, and has perceptive comments, possibly because he writes himself, and he reads constantly. He speaks very specifically about craft. My daughter—I think because she’s a teacher and because she’s always been interested in my students—sees what I do as having a valuable connection to community and career. She’s proud of me because of that. But she feels her privacy is violated when I write about her. I try to respect her not wanting the world to know anything about her, and she in turn tries to look the other way when a poem’s context involves her life.

RR: In terms of literary parentage, how did you carry on the legacy of the mentors who mentored you, and are there ways in which you felt that you should do things differently with your own students?

CM: I think I was first mentored by the written word. What I wrote in high school was not acceptable to my teachers, and though I loved the romantic poets and Keats, I felt disassociated from their voices. Aside from a few Frost poems, we didn’t read anything from the 20th century. When I read “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” in the Louisiana Tech library, I’d never heard of Eliot—I thought I’d discovered him myself. I started writing poems because I was teaching poetry to high school students. It was the 60’s—everything in the world was changing and those changes were reflected in the new textbooks. They put me on the textbook committee to help decide which books the school should adopt. I was introduced to amazing poets: Elizabeth Bishop, Robert Lowell, Denise Levertov, Anne Sexton, Sylvia Plath, James Wright, James Schuyler, Allen Ginsberg, to name a few. So I came in through the back door: I read poetry constantly. The head of the English Department at my little school in rural Texas pretty much let me do whatever I wanted. I think that first year, I taught a poetry unit for three months. I went crazy reading these contemporary poems to the kids and getting fired up about them and getting the kids fired up about them. Even then when I started writing, it was a surprise. I had a notebook I wrote in right before bed, and gradually I realized I was writing poems, not journal entries. It felt like a complete accident.

I taught high school for five years. During that time I spent one summer up in Seattle, Washington, and by total happenstance I was admitted into Richard Hugo’s workshop at Seattle University. He encouraged me to come to his MFA program in Montana that fall. But I had a teaching contract in Austin, Texas, and no money, so I went back to Austin. By then I knew I wanted to get an MFA so I could teach in a college rather than high school, which would give me more time to write. Three years later I ended up at Columbia. I was 27; I’d already been writing seriously for about four years, a big difference between me and the other students. At the time there were very few programs in the country and almost everybody else was right out of college. I didn’t realize that I had been studying poetry all that time I was teaching—I just wanted the degree. I had wonderful teachers, and I took their attention for granted. I didn’t know how lucky I was to have those mentors. They were very different teachers from one another, with different agendas, but they all pushed me. Those poets—Mark Strand, Phil Levine, Stan Plumly, and Stanley Kunitz—became my models as I progressed as a poet. But I don’t know if I’ve changed in terms of the way I teach now and the way I was taught because it didn’t seem that I was introduced to poetry so much by a teacher; it was more that I had already found my own way of studying it. Reading is the best teacher: I still believe that.

I certainly sometimes find myself saying things that seem to come straight out of my teachers’ mouths. I never really rejected anything my teachers said, not outright, but some of their warnings and advice I didn’t appreciate or understand until much later. As a young writer I was so wrapped up in myself that much of what they said was going in one ear and out the other. And then years later I would be faced with a problem in a poem and think, “Oh, so that’s what Stanley [Kunitz] was talking about.” I continued to be instructed long after I was a student because when I was a student I couldn’t be instructed.

RR: It’s not in one ear and out the other—it just stays there, filed, until we know what to do with it. I have things that come out of my mouth that are straight from you and from Eavan [Boland] and Linda [Gregerson]. They come to mean something as the work finds ways to engage those problems.

One of your strongest pieces of advice to me as an undergraduate was to be wary of looking at poetry through the lens of the critic. You said we would not learn poetry by dismantling it in a criticism class—we had to find our own way into it and read it as someone engaged in the craft.

CM: From the beginning for me, it was all about the emotional experience. That would explain why the language of previous eras, for example, would not have affected me like the language of people who were living at the same time I was. I couldn’t easily connect; it was as if the language was not fully available to me. When I studied literature I felt removed from the nexus of the poem—the essential emotional connection that was at the heart of the language. I wasn’t a very scientific reader; I had to learn to dissect the poem. I always felt the poem before I had any idea about its meaning. A good poem is essentially unknowable, and I get impatient with critics who will assign meaning or even characteristics of personality to a poet by virtue of what they’re interpreting on the page.

RR: I found that very useful early guidance. It was a supportive framework to have the idea of the poem being unknowable, that you have to approach it and try to communicate with it rather than trying to analyze it for some hidden key.

CM: It’s just that the critic creates a self-importance around what they’re saying. It’s very hard to forget them when you’re reading. You’re arguing or agreeing with them, rather than engaging directly with the poem.

RR: Maybe that’s why someone like Sylvia Plath is so hard for so many of us—that criticism and analysis of her biography is so powerfully imposed on the work that it’s hard to just read it without hearing their words and thinking about what happened to her. I’ve actually had the chance recently to teach her poems to students who didn’t know who she was—her time is far enough removed now that a lot of people don’t know her story. I presented her as if everyone knew who she was and someone asked me, “Should we know this person?” I thought about explaining it, then stopped myself and said no, we’re just going to read the poems and you tell me what you see. It was so much weirder and more interesting, and a new way for me to be able to engage with her work.

CM: I bet you’re a good teacher, Rachel.

RR: I hope so. I had good teachers, Cleopatra.

—

Rachel Richardson is the author of two books of poetry, Copperhead (2011) and Hundred-Year Wave (2016), both selections in the Carnegie Mellon Poetry Series. She has received fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts, Sewanee Writers’ Conference, and Wallace Stegner Program at Stanford University. Her poetry and prose appear in The New York Times Magazine, Lit Hub, New England Review, Kenyon Review Online, the Poetry Foundation website, The Rumpus, and elsewhere. Rachel is the Co-Founder and Co-Director of Left Margin LIT, a literary arts center in Berkeley, California. She also directs poetry programming for the Bay Area Book Festival. She lives with the writer David Roderick and their two children in Berkeley.