by Andrea Blancas Beltran | Contributing Writer

Hoa Nguyen is the author of several books of poetry, including the recently published A Thousand Times You Lose Your Treasure (Wave Books, 2021), As Long As Trees Last, Red Juice, and Violet Energy Ingots, which received a 2017 Griffin Prize nomination. Recipient of a 2019 Pushcart Prize and a 2020 Neustadt International Prize for Literature nomination, she has received grants and fellowships from the Canada Council for the Arts, the Ontario Arts Council, the MacDowell Colony, and the Millay Colony for the Arts. Her writing has garnered attention from such outlets as The PBS News Hour, Granta, The Walrus, New York Times, and Poetry, among others. Born in the Mekong Delta and raised and educated in the United States, Nguyen has lived in Canada since 2011.

Hoa and I spoke over the phone from Toronto, Canada, her home base, and my hometown of El Paso, Texas, just as both cities seemed about to be ordered into isolation again. Hoa graciously shared an advanced copy of A Thousand Times You Lose Your Treasure, and in a conversation that spread well over two hours, Hoa and I discussed this new work, which is a new form of engagement with poetry for her. We also discussed her experience in making work about her mother and birthplace of Vietnam, memory, displacement and the Vietnamese diaspora, language, music, storytelling, influences, affirmations, and even the bountifulness of cabbage.

Andrea: Thanks for making the time to meet with me about your forthcoming book, Hoa. I was listening to your conversation with CA Conrad for their Occult Poetics Radio podcast and you mentioned that you had been thinking about this book for decades and that distance is very much a part of the project . . . and so when I was going through your previous interviews, your earliest mention of this project is in 2008. I was hoping you would talk more about the evolution of this book in terms of time because I know that’s something that’s been on your mind quite a bit lately.

Hoa: Yeah, I think that 2008 interview is with Joshua Marie Wilkinson.

Yes.

With Bookslut. Towards the end, I say something really flippant like, ‘Oh, it probably won’t, I’ll probably never write it.’ (Laughs.)

Yes! I think you said, Really, it might never get done.

It might never get done . . .

But it’s done!

It’s done! It’s funny, I think about that because that’s a kind of story we tell ourselves, right? For one purpose or another, we might negate whether you are up to the task as a way to actually write it . . . and also, it’s like . . . It’s not going to be done—because I am not actually sure that I did it. (Laughs.)

And this was something I was wondering about—or this was a question I wanted to ask (Hoa still laughing) because you said that you had been—what was it—I think you used the word “failing.” Like trying to put it all together yet failing, and so does this feel like it’s achieved any completion, not that completion was necessarily what you were going for . . .

Right . . .

But hopefully there isn’t a pervasive sense of failure (Hoa laughs) because I think—ah, there is so much to say, really—about this book.

I think I did something. (Laughs.)

You did A LOT. Really.

(Laughs.) I did a thing. No, I—thank you. It’s funny because I was talking to my friend Damian Rogers here in Toronto, she’s a poet and was also writing with a shape that she has had in mind for a while that has to do with telling a story about her mother. She accomplished her book, which is called An Alphabet for Joanna, and it just came out this fall, and it’s really poetic and gorgeous. And she was talking about actually encountering something, a record of an event that her mother had shared with her that she didn’t know prior to the book, so it’s not in the book, and she knows that she wouldn’t change it. And I said something like, you know it really kind of points to the fact that the writing’s never done. It’s that you do something and maybe this new occasion or this new information might find a new circling of your curiosity, your engaging, right? Circling the distance.

Sure.

But I think in the earlier years of my writing, before 2008, it just mostly had been a kind of site of distance and memory. This sense or this concept of memory as place, memory as displaced, is something I think share with a lot of people honestly, especially diasporic people . . . first generation people, one that is a significant shaping of why you are who you are where you are, a shaping that includes displacement, psychically and geographically displaced in big shifted way, a way that can come about in convulsive, traumatic vehicles, right? These that continue to articulate themselves in your life, and yet that separation creates a kind of barrier, let’s say, or gap—and a kind of seeking transpires. So I think I’ve been thinking about that, which is a general kind of consideration of a life . . . After I wrote the book, I wrote about the book for my friend Renee Gladman, who remains a dear friend and colleague since we first met at New College where I studied poetics in San Francisco back in the early 90s. Renee was editing a collection of essays or “afterwords” for writers who were interested in adding or addressing, to comment on or extend as a bridge across from a completion (the book) to this moment. It was a great chance to reflect on writing A Thousand Times Your Lose Your Treasure. I named the essay “Midnight Saturn Bassnote” and it will appear in the Black Warrior Review. Anyway, there I said something like my mother’s life previous to the U.S. was just like this blank. I wrote: “an impervious surface, a smooth raised scar.” There were evidences—clearly—of the before-life but they were so submerged and unavailable that they became this sort of site of unknowing and also therefore unstoried. They weren’t fully narrated.

So there’s a certain way that the poems seek a new narration, I think, one that hadn’t been there. And yet, maybe still isn’t there, but it is its own thing. The narration that I give is not really seeking to summate, which I think was a problem that I encountered as a younger writer—and I think I also understood that I wasn’t properly equipped yet of the capacities and perspectives that would be asked of me to be in dialogue with this difficulty . . . Writing A Thousand Times Your Lose Your Treasure was kind of like being in a dialogue with difficulty, which includes many things. It’s the difficulty of seeking to understand someone else’s experiences and stories when those are remote to you. There’s also the difficulties of language itself, the ways in which narration can over determine, the problems of purposing story and unintentionally creating an undoing of the very thing that you’re trying to do, which for me was to perform something in language that operates to liberate and, so, it took a lot of time. (Laughs.) And I think that writing it, finally, that writing it also took distance from sites of trauma, from traumatic events, really, that precipitated the most obvious difficulty which is moving across the globe for my mother, experiences of wartime, of living inside of a violent phase and hardship lonely times . . .

And then being in the United States at that time and also having to experience an entirely new kind of violence in terms of the expectation to acclimate to a life here, so . . .

Yeah . . .

So, yes, there is definitely this idea of evolution/revolution, of truth and of history, that I think spans this book. I’m interested in—this may be a very broad question—I know you’ve spoken before about your mother tongue, and as this book is making its way into the world it not only deals with the loss of a mother tongue but essentially of your mother, and so I didn’t know if this is something she knew you were working on. I know she spoke with you about some of the photographs, but I don’t know how you approached that with her or if it was something you approached at all, or if this is entirely too personal of a question . . .

It is a completely inbounds kind of a question! It’s interesting, people are often curious what her response is, if I was sharing the work with her. I had—I should back up and add that my mother passed away in the spring of 2019 after a long illness; she had entered hospice in the beginning of that year and passed on June 9, 2019, and in fact . . . let’s see, let me make sure I have this correctly chronicled. The earliest poems that I wrote towards this series I began in 2012, and I only got as far as maybe eight to twelve poems, something like twelve poems from my first focused attempt? And I recognize it as an attempt in that I had been sort of tentative to try to write towards this idea I had: to write this narration including a biography of my mother’s life in verse. First of all, that I was leading with this “idea” was a novel thing for me as a maker. I’ve always been a different kind of poet, you know, the kind of poet who writes and collects poems and sequences them borne out of a life that’s a lived engagement with poetry. That’s a really basic kind of practice for me. But this was a more intentional and aimed proposal, and I since always had to have too many jobs and was also raising two young children, I hadn’t felt I had the capacities available, the resources available, to engage with this undertaking. But anyway, in 2012, I managed to secure my first ever writing residency, and it was there at the Millay Colony that I wrote the first poems towards the sequence that became A Thousand Times You Lose Your Treasure—and I know you had asked me about my mother . . . (Laughs.)

It’s ok—it’s all applicable.

(Laughs.) Yes. When I emerged from that experience I had these poems and I want to say that—I mean she knew—I would always ask my mother about her life, you know, in the way that I would compare notes with other diasporic people or other children of parents who’d lived through genocide or war, so there’s a certain pattern among those that I’ve spoken with whose parents lived through say the Holocaust which is you just don’t speak of it. You don’t speak of it because there’s guilt and inchoate pain and it’s better just not to examine any of it, especially if you don’t have a way to manage what comes up with it. So, when I would ask her to relate the stories so that I could understand, something I tried to slip into conversations randomly, like, OK, so you were in a motorcycle troupe . . . So wait, how old were you? You know, those basic questions: OK, so what did your parents do for a living, you know . . . (Laughs.) It was very mysterious to get to know your parents’ story when they’re really opaque about it, and typically she’d be very brief. Any attempt to record something would immediately fail because she would just say two sentences.

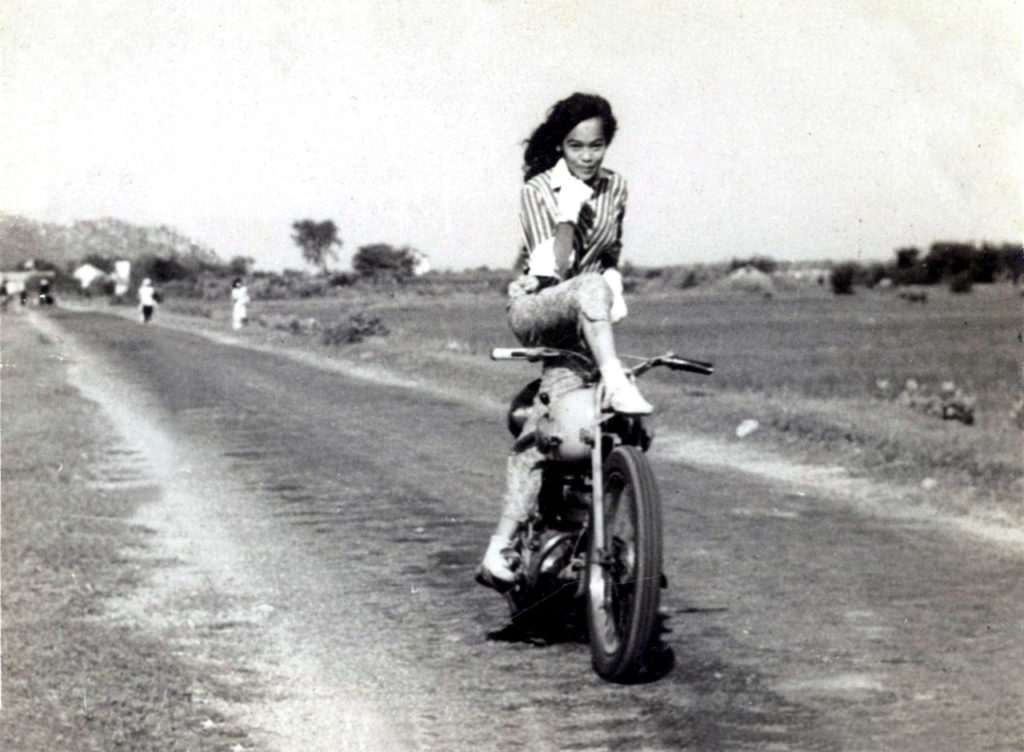

In fact, one time, she had had these images of her days in the motorcycle troupe . . . well, actually, growing up, we only only four photographs available to us from her circus days and what’s in A Thousand Times You Lose Your Treasure include several more that came from my family’s personal photographs that surfaced after her passing. But the ones that we did have, they were gorgeous. Two showed her performing on the wall of the barrel—what she called the Barrel—the Wall of Death that they ride inside—one with another woman and one by herself. We had a picture of the five women in their uniforms for a promotional photo and then a photo of her riding on a road, hands-free. So, I guess it was sometime in college, I had two of them blown up, or maybe she already had them enlarged and I took possession of them: I had them framed, like inexpensively for a college student but very proudly with my own money kind of thing, and I had them on my wall of my first apartment. And when she saw them she looked around and was like, Well, why don’t you have any current pictures of me? And she went to the mall to the Glamour Shots and got pictures done of her and so she brought me her Glamour Shots! She was like, Here’s a picture of me. (Laughs.)

Wow. Awww.

I know! (Laughs.)

Wow. That’s . . .

So good, right? (Laughs.)

Yes!

But that’s very illustrative of the completeness of her transformation to the person that she became. And also a kind of disconnection like, what do you really see in these images, in a way . . . She would literally say, That was a long time ago. And so, it was sort of very not available to me. Ok—I’m still coming around to your original question: so then when I finally was able to produce some poems including a poem about a story she had told me about her naming that I turned it into a poem. My friend Kyle Schlesinger and his small press Cuneiform Press, based in Austin, made a beautiful broadside of the poem that included an image of her riding on the road while doing a stunt so I gave her a copy of that poem. And I presented it to her and I read from the small suite of twelve poems that I wrote during that time, and she was very moved. She said, You remember more of my life than I do.

She took the broadside for her room, and then I came back later for a visit and I saw the broadside leaning on her dresser, there was a Kleenex box covering the poem and it was just her picture showing (laughs). I was honestly fine with that—she just felt like my word stuff was not her thing, she was just not a literary . . . Of her reading I knew that she read when she was a girl these novels that were romance novels. Her family did not send her to school as a child they were like, No, there’s no reason for you to go to school, she grew up on a family farm and didn’t have options. But even then she understood that she wanted to read and was able to learn on her own (her friend taught her to read, the story goes, by the river where they had gone under the guise of washing clothes) and as a teenager loved these particular romance novels translated from the Chinese that featured a beautiful protagonist who had adventures and probably died tragically, but—and actually, that’s who I’m named after. She translated that name into Vietnamese and gave it to me, but she actually first gave it to her first daughter who was named Hoa, who appears as a kind of little ghost in the book’s sequence.

This clarifies something for me . . . because I understood about your mom’s name, but then when I encountered the poem about the first daughter I was curious. There are so many echoes between you, the speaker, of the poems, and your mother, your mother’s life.

There are different voices in there . . .

Yes, I definitely get a sense of different speakers, and there are some poems in which I feel it is her voice that is speaking . . . This conversation of the broadside and the way the Kleenex box was sitting on it reminds me of a line in the opening poem “Seeds and Crumbs” that concludes:

the future’s not ours

to see tenderly

And so, speaking of contradiction, I feel like your writing resists this sort of sentimentality while also allowing space for it but not in this overwrought or saccharine way, if this makes sense.

Oh, I’m glad that that’s your reading experience of the poems. Thank you so much.

It definitely is.

I’m interested in how there is also space for humor or play or a kind of voice outside of time, right, that isn’t really attached to feelings that are located in the individual particular and are also specific.

I know when we were originally emailing about this conversation you shared those Jack Spicer lines (“words must be led across time, not preserved against it” and “a poet is a time mechanic, not an embalmer . . . ”). This led me to Cecilia Vicuña, and she was coming back into my thinking about your work. I remembered that at one point she had shared in one of her poems about Charles Olson who’d said, Memory is the future because you will remember in future tense.

This really resonated for me in terms of your writing and all of the different dimensions—tenses but more so dimensions—that it took even by way of form. You have poems, letters, ghost stories, biography, history, hauntings—it’s like this wondrous collage of—ah, I don’t know—it just IS wondrous. One thing that I was thinking about as well is I remember you saying you had this distrust of the sentence (Hoa laughs) because of the ways it has been weaponized historically, so the reader is encountering more, especially by way of the letters, of the sentence. I was wondering if your thoughts had evolved on that or if you had found a way to work around that, which I think you did.

H: I like to think I did. (Laughs.) Well, I’m still kind of messing with the sentence, you know, even if I’m producing sentences.

Yes, I definitely think you are, and the space that you employ between sentences really makes everything seem that much more—I don’t want to say powerful—resonant, louder, if you will, especially in the poems like “Made by Dow” and the one line poem “Hagiography”:

a saint she ain’t

And then the rest of the space on that page!

(Hoa laughs.)

I’m so glad that you pointed that one out. Right, I like to think of it as a playful repositioning of sentences that redefine as it were.

I loved it, and it was open-ended, working against this linear narrative but it was very declarative as well.

I’d like to think my mom would appreciate that one especially. (Laughs.) Another item that came to my attention after she died was her immigration papers, one that attested, for the purposes of passage, that she had the attribute of “a well-behaved woman” (laughs). It is very funny in a great inside joke kind of way.

There were these really great moments of humor. I even found humor in your opening poem with the song “Qué Será Será.” It was humorous, but in knowing about that song and how it figured in that [Hitchcock] film it was also kind of like a building of suspense. It just really is remarkable how a single line in one of your poems can do so much work.

Thank you.

I’m trying to be linear about this interview, but then it’s pinging me to other questions I have. One of them is about the inclusion of songs because these songs speak to maybe a certain part of one’s youth, and so I was hoping you would talk a little more about how songs appear throughout these poems specifically “Qué Será Será” and “Oh My Darling.”

I include in the back of the book the anonymous diviners and singers and fellow time travelers. I think growing up my favorite section in the library was the myth and folktale and ghost story section. All of those things seemed to somehow be related in my investigations. The stories that we tell about hauntings, the mythic stories—folk tales have ghosts in them, too, right? And ballads often do. There’s the whole tradition of the ballad in English, how they’ve been part of an oral tradition of collaboration and elaboration and often these songs are held in common and added to, changed, adapted to the conditions of the new place where the new events of the occurrence. Ballads of loss and that recall the dead. Also murder ballads. As with folk traditions, the particular or details will change, the names or place names will change . . . I remember in English class the Anonymous poems were the ones that drew my attention most, in part because I suspected they were written by poor people, by women—and even then, maybe I was seeking those voices or sites for under-articulated or missing parts of the archive inside those pieces, right? Which are actually the most important pieces in a way.

We go back to the different dimensions—or I’m thinking about your poem that I love so much, “Write Fucked Up Poems,” and the word you use: “cabbaged.” It’s like the song lyric as a haunting, this cabbaged resonance, which I really love in all of your work.

And cabbages are so important. (Laughs.)

Yes. (Laughs.) They are. (Laughs.)

And they’re really quite beautiful . . . (Laughs.)

They are beautiful. Their blooms are extraordinary, really.

A really good food for the poor. It’s a very generous plant.

Yes, we can stretch it a long way. Off subject, in not going to the grocery store much at all and trying to stretch food through this pandemic, cabbage has become even more of a staple in my fridge.

Right. Winters well, hardy. And you can ferment and pickle it. There are so many things. (Combined laughter.)

This is such a metaphor for your work!

(Laughs.) Well I am interested in those traditions, too. Food ways are really important traditions, and they’re held in those same kinds of relational commons. They’re rooted in places and they’re passed through kinship ties. And they’re the place of the hearth and women.

Yes, I remember that part of your conversation with CA about your love for nettles, and it felt like such a little nod from the universe yesterday . . . when I was making my notes I’d made my last bag of this tea made by a local herbal healer, and when I pulled out the label from the tea bag I had forgotten that it was called “Sustenance for Dismantling the Patriarchy.”

(Laughs.) So good!

I know, I thought, oh my goodness, what a perfect thing to encounter today and to be sipping on as I’m trying to organize all of my thoughts about A Thousand Times You Lose Your Treasure. Food always brings us back.

I think in that broadcast I talk about my plant communication from yarrow. And yarrow makes an appearance in the manuscript, too.

Yes, I did notice that. And I feel like there was something else that appeared . . .

Oh, the tower.

Yes, the tower and the I Ching . . .

The I Ching was hexagram 51, the arousing thunder . . .

Yes, shock and arousing thunder.

But, anyway, yes, nettles. It’s funny because nettles just came up yesterday. My teen boys were talking about carnivorous plants, you know plants that have digestive systems and trap flying insects in various methods, so then the proposal was, What is the most aggressive plant? And we thought, Hey, it might be nettles. (Laughs.)

I think you are probably right.

But it’s so good for you. It’s really a defense mechanism of like, Don’t fuck with me. (Laughs.) But also, You can approach me but just be right.

And then, in a way, this brings me back to your mother. What I really love about this book is that I know when a lot of people are talking about Vietnam—I think it was Viet Thanh Nguyen (in a conversation with David Naimon) who said, When people say Vietnam they automatically think about the war—so I love that these poems live outside of this idea, and they also live outside of the traditional white male centric narrative or mythos, and you do such a beautiful job of capturing her courage but also her irreverence. I didn’t know if that was something you’d intended to work through in these poems or if it just happened.

No, it was very intentional. (Laughs.) I wasn’t interested in writing from those perspectives. They aren’t shared, first of all, so why would I? Also, there are so many stories—every story is that perspective when you come to the country of Vietnam, you know. Or it’s the traumatized victim.

Yes—this is what I have written in my notes, that you portray your mom as a woman who had so much agency and who was not—did not —want to be a victim, and did not position herself as one, and you see her outside of just being in this mother role or immigrant—I don’t want to say role . . . I don’t like that word, but, yes, your portrayal of her is so dynamic and it really captures her spirit.

Thank you. I’m glad that it feels dynamic.

I printed and cut out the photos that you used to open and close the book and taped them next to each other on the page. I even wrote next to the side of them, What a gift Hoa has given her readers, just with these images alone because the movement between these two photographs from beginning to end . . . you conclude A Thousand Times You Lose Your Treasure with your mother stuck—not stuck—but left in perpetual motion. She is in flight and it is so moving to me as a reader because it is such a moment of tenderness and intimacy, but also, damn—she was bad ass.

She was really bad ass.

When I say this book is extraordinary, it really is. And so I don’t think it was a failure in any sense of the word although it may seem that way to you . . . because I’m sure you have so much left that you are thinking about and working with even now.

I want to go back to something you had asked me as I started telling this story but then I stopped, which was my mother knowing that I was writing this . . . so in February 2019 I had a classroom visit and performance schedule at the University of Maryland, which is about forty-five minutes from where I grew up, where my mother still lived, and where I had done my undergraduate degree in psychology. My mother had been in home hospice for about six weeks when I read there from poems that would become A Thousand Times You Lose Your Treasure, although I still hadn’t advanced that far into the work. I was about to enter into a second residency—my second ever residency—at McDowell where I ended up putting down more foundation and then spent the fall tearing it all up and rewriting everything until I finally finished it . . . but, my mother came to that reading in February, with some tricky logistical and physical difficulty. I read poems from A Thousand Times You Lose Your Treasure including poems that were based on her life and ended my set with images of the four photographs of her in her motorcycle stunt days projected on a large screen behind me. The audience was large and everyone knew my mother was there and viewed these amazing images of her riding the Wall of Death which of course brought the house down. It was a deliciously happy moment and the next day, when we had a chance to talk about how it went, she says to me, I am famous. (Mutual laughter.) And I was like, Yeah, Mom, you are famous.

I love that!

It’s so good. And I was like, Exactly! I hope that I do you proud. And she was like, It’s so amazing! I don’t really know what you’re talking about half the time, but I know it’s good. A lot of people came out. They were all in line to buy your book.

She often shared that she was proud of me and would say things like, who would believe that that toddler on my hip, a statement that is based on a photo, a photo that I actually can’t locate despite looking and looking and yet can see it . . . You know how that is, where it’s like the photo lives but is an image without object . . .

Yes! Yes.

So, there’s a photo of us where I’m on her hip, and I would’ve been eighteen months old and it was two weeks before we left Vietnam, and she’s dressed in her traditional, like her fanciest outfit, which is an Áo Dài, and it’s taken in her backyard. And she was fond of saying, Who knew that little girl I had on my hip would become so famous.

I’m thinking now how special it is that she trusted me to tell her story, that she never said, Don’t write about this, or anything like that to me. And it’s funny because talking to other people about their parents including other Vietnamese diasporic people about what they know about their parents, I realized that actually I know more than most of the people I talked to, that she shared a few intimate things with me even so . . . like what I write about in that poem “Mexico,” that you might remember, a longer narrative poem, that narrates a love story that doesn’t end well for her . . .

I remember . . . I do want to ask you about the longer poems, but I want to mention that I recently, this was maybe a month ago—I don’t know, my concept of time is even more off than usual—there was a conversation with some of the women who are part of the She Who Has No Master(s) collective, and this was a common theme, that we (the speakers from the collective) don’t talk about these things, or that things seem to be much more on the surface level of conversation when it came to deeper conversation with parents, especially mothers.

Yeah, I think I benefited, in a way, from the fact that my mother didn’t really have a mother; she was raised by her grandparents and an aunt and uncle, let there without parents. Her mother left the scene early and her father was away traveling with the French at the time—this left my mother unprotected and limited and so she left home when she was fifteen . . . all of these meaning that she parented in a way that was a little less traditional . . . although she was traditional in other ways . . . such as views on marriage or gender roles.

In your conversation with CA Conrad you had said something like, My own practice of healing is to release the women, and that is definitely something that—you know, I try not to use the word achieve—but I think that you achieve that in the writing, but also just the way you have the photos laid out and then that concluding photograph, it’s like her release.

Thank you.

Again, it’s just very moving. I do want to come back to longer poems because being so familiar with your work, I did note this evolution of the line, not only line length but poem length in this book. You have “Mexico,” which is almost four pages, a longer poem “Made by Dow,” “View from 2020,” “The Flying Motorist Artist,” so the reader is encountering longer poems and I was wondering in what ways was the writing/making/organizing of this collection different compared with your previous books?

I worked this manuscript in a way I hadn’t really worked any manuscript before. I think both with attention to the total, the sequencing, the kinds of poems, you know I put all the poems on the wall and I put sticky notes on them that were coded in different ways so that I would understand the kinds of poems that were there. Like here are poems that have these kinds of modes or pieces of information or tones of address. I was interested in the individual poem as part of this group, and I was interested in working in the short song form obviously with the sonnets in there, and there’s longer song forms . . . it’s funny because I think in that 2008 interview or a different one where I talk about reel to reels that I listened to when I was really small . . .

Oh, yes—it was that one!

So one of the reels I listened to was a collection of Johnny Cash songs, and I remember listening, so he had a lot of story songs, right, and the longest one, which I actually could hardly listen to more than once because it’s so sad, was the story of John Henry, which again is also a tragic song, it’s also a folk song, it also has encoded cultural information about racial injustice and striving yourself to death. I think that there is a way I was tapping into the sort of story song space, which I understood needed to have a different mode and a different duration. And I was also thinking about those ballads, those traditional ballads, but even more how they might also have a relationship with these sort of talk songs, which are also storylike and tell both a specific story and a larger story.

The specificity of the story becomes this bigger frame. I was very intentional and took a lot of things apart and put them back together again. And threw things away. I also really wanted this to be an experience that could feel like storytelling but a very different kind of storytelling.

Yes, that’s what I loved about it. It wasn’t linear in any sort of way, and you had mentioned your poetics of a lived practice, and I think that still really shines through but then you have the story of Diệp, or Linda, your mother . . . and now that I’m looking back through my notes, I think you talked about that reel to reel in the podcast Into the Field with Steve McLaughlin, and you also said that you wanted to be a ghostbuster (mutual laughter) when you were growing up, which I think you kind of become with this collection, too. You turn these myths or these stories on their heads and revision them, so I loved when I heard that in the podcast; it was like, Oh, she is, she is a ghostbuster! (Mutual laughter.) It was great.

Oh my gosh.

I feel like I could spend an entire day talking to you about this, and I want to talk to you about your influences, but before I get to that I want to ask you, since we were talking about form and this being a different mode of working for you, I was hoping you’d share more about the inclusions of the lessons from that colloquial language course. I almost resist asking about language, but I really thought those moments in this collection were very matter of fact but also quite moving in what they withheld if that makes sense.

Yeah, thank you for sharing that response with me because that’s awesome. (Laughs.) I put in the back of the book the references to an edition that came out in the nineties that came with cassette tapes, something that I bought at a big expense for me at the time while a graduate student in San Francisco . . . I remember—this memory that might be two separate incidents that I have conflated together, but the memory is that I bought them in a failed attempt to attend an event in Berkeley. I was living in San Francisco at the time, and four of my fellow students at New College then were driving to it, riding in Mike Price’s big yellow 1970s Impala. As we near the school, we get stopped by the cops—I don’t know if Mike rolled through a stop sign or whether our vehicle just looked suspicious. The cop looks at everybody in the car and for some reason he directs his attention to me. I’m in the back seat—it’s a convertible remember and the top is down—and the cop asks, Do you speak English? to me in the back seat. And it was a bizarre non sequitur and my blue-eyed friends of the European extraction didn’t know what to say and I didn’t know what to say. The cop let us go without incident and I didn’t go to the event and instead I said to my white friends, You know, I’m just going to go to this bookstore over here. And I bought myself this expensive language less in colloquial Vietnamese that came with six cassette tapes and a little booklet.

At the time I turned my attention to figuring out how I might make it possible for myself to visit Vietnam. The country had just opened to Westerners and U.S. passports; travel there up to that point was prohibitive. Even so my mother was not interested in going back, and since I didn’t speak Vietnamese and we didn’t have any kin left back in Vietnam or connections to a diasporic Viet community. I felt cut off in an unbridgeable way. I was just talking to my other good poetry/writer friend here in Toronto, Barbara Tran, about this, about the different diasporas of the Vietnamese diaspora. I am also mixed race which can function as another form of distancing and marking of difference.

Anyway, so I listen to the tapes and am like, fuck: it’s really hard to learn how to speak Vietnamese from these cassette tapes, and I’m talking to my mom on the phone and she’s like, Oh, well, that’s probably a Northern accent . . . and I’m like, forget it, my mom essentially hinting that this language course was useless anyway since I of course wanted to learn to speak southern Vietnamese and not speak with a northern accent. So I was left with this useless book and these six cassette tapes, and then I dragged them to Austin when I moved to Austin and together they sat on my shelf until I turned to the little book and turned some of it into poems.

Oh my gosh, it’s like the language itself is just being evasive.

Yes. And the objects themselves being these emblems, so I’m happy that they also function in the sequence in those ways. That’s the whole biographical event, personal event and meaning embedded behind the poems that contain these conditions of language and languagelessness.

Yeah, I understand that. The Spanish I grew up speaking and learning from my grandparents here in El Paso is considered a very colloquial Spanish, what is called border Spanish, and so when I’m learning other words from people who might be from Puerto Rico or from Guatemala and I repeat them to my mother she says, That doesn’t mean that here. There’s always this inaccessibility when it comes to the language, so I can’t even imagine what that would feel like being in Vietnam for the time that you were. I’m glad you had people there, you had a greater sense of connection and community while you were there.

And mostly, it’s actually entirely in part being able to find other Vietnamese diasporic writers through DVAN, which is the Diasporic Vietnamese Artists Network, and then a collaborative within that network that Dao Strom started called She Who Has No Master(s), which is that reference you mentioned earlier in conversation . . . She had put together a collaboration, an invitation that I was able to accept, to go and work in collaboration and then present at the American Library in Paris, but we had this house on the island of Corsica that was gifted to the collaborative to use as a site to get together. It was the first time —that was in 2016—so, really, I’m super, super grateful for that because I don’t know how I would’ve found my way to the material. In fact, when I was in Corsica I wrote a poem that really helped unlock an approach to the work. I think the poems that I had been stalled on, the poems I wrote after throwing the I Ching, I didn’t even tell other poets . . . I was like, Well, I’m writing poems, but they’re poems I’m not writing, which are in a terrific stall. So in this sort of stall, I wrote this poem and I realized, Oh, I don’t have to do a kind of reconstruction, I can just still write poems. (Laughs.) I think that I thought because it was more aimed at non-efficient storytelling that I somehow had other responsibilities, but no, I just had a responsibility to the poem.

I feel like there was a specific interview in which you were talking about giving a workshop when you were on the She Who Has No Master(s) retreat and the poem that you’re talking about coming out of a prompt given for a work session there . . . Having been in three of your workshops now, I feel like poetry is something that happens in community, whether it’s with other writers by way of the workshop or our guides by way of your work and our other guides meaning whoever we’re reading at the time, James Schuyler or Bob Kaufman, etc., so I was wondering, because you are so open and generous about your teachers and poets and writers in general that you love, are there any particular writers/people/movies/anything that guided you as you were working through this more intensively, or more intentionally?

Yeah, one of my page mothers, I’ve spoken of her in this way before, is Joanne Kyger, who I met in San Francisco, or when I was living in San Francisco she lived along for thirty years about an hour and a half north on the coast and was a student of Spicer and Duncan, Blaser, the Magic Circle in San Francisco when she was in her twenties, which would’ve been in the late 50s, but also her work is in a long dialogue with Buddhist thought, which some of my work is, and not in the same ways that her work is and that’s Joanne Kyger. She was a poet with a terrific relationship to storytelling inside of the space of a poem. Biography, day book, place, attentive to place and also the environment as alive around her.

I think that relationship for me is really important, that the earth is a living entity that I am a constituent of, and part of the whole cosmological, inter-relational, sort of thing. And so she was really important to me—in fact this morning I was just listening to the audio archives of Naropa’s incredible archives—I think I went in because I’m preparing for workshops on the poet Fred Wah, who like Joanne had studied with Robin Blaser, and Robert Duncan and Spicer had come to Vancouver, and he was a student in the sixties at British Columbia in Vancouver, and so he has this new book out called Music at the Heart of Thinking, and it’s very Olsonic. Olson is a poet who was really foundational to me as a young writer in part because of New College. I studied with a biographer of Olson, the poet Tom Clark, and Olson’s work, The Maximus, is often noted among his works, and I was just returning to that and Projective Verse thinking about poetics of energy. I think about energy and language and texture, transference of energy between the occasion of the poem, the page and the reader, those all sonic sort of proposals that Joanne, when we would talk, would say that she would read that essay at least once a year and she always found a relationship to it, as syllables, a language as syllable seeds that were on a necklace, which was really useful to me. When we would visit her in Bolinas where she lived, she had incredible gardens that she had this really beautiful relationship with, with a little bird table for the quail and trimmed, shaped hedges . . . Art and books would be handed to me . . . She was the one who introduced me to Sei Shōnagon’s Pillow Book. She had studied with Spicer and with Robert Duncan in these informal meetings and workshops and she made a point of sharing with me that Duncan kept a very magical house with his partner Jess [Collins], the collagist, and that he, how did she put it, he would attend to the domestic gods of the home. She said that this from Duncan gave her permission to do the same. And I understood this too, that it gave me a revelation of permission. I think Duncan might relate it to the ancient Greek notion of tenemos, it’s like the sacred precinct, the space that you attend to in the gestures of attending to things, right?

Yes, I’m glad you use that word—that was one of the words I was looking for when we first started talking—how your poems really reflect your deep levels of attention to your influences, this notion of attending to things . . .

Thank you.

When I think about your work I think of two things: disco balls because all of the light, forms of light that they attract and reflect and refract . . .

Oh, that’s so good—you know Olson would call it tesserae, which are the little individual tiles of a mosaic . . .

Ah, I like that . . .

Which has been a really important kind of metaphor for making up a poem . . . but a disco ball is better. (Laughs.)

Yeah, a disco ball does it for me when it comes to your work! (Laughs.) Because it’s also just so brilliant, but then I also think, when you say earth, so much about soil and this level of attending to things, and soil being a place where things are planted, where they’re tended, where they’re cut/shaped, things die there and then come back to life . . . I think your poems also do that. There are so many different metaphors for your work—definitely multidimensional.

Thank you.

I know you had talked about portals, portals by way of the tarot and the I Ching, and dreams are also very important to you, and I know that there were some dreams that made their ways into these poems, but I was wondering if there were any other affirmations you may have received from the world as you were working on A Thousand Times You Lose Your Treasure.

That’s a great question. That tower thing is really interesting to me. I started telling you about drawing the Tower card—that I had this tarot reading where the Tower card was figured directly before my first visit to Vietnam in 2018. Seeing it I was prepared for something calamitous: the difficulties that the Tower can bring comes with a sensation of a ripping away, constructs falling down, like you’re falling from the top of a high-rise or crashing, but instead it was the symbol of a chance encounter with the very motorcycle troop performance style that my mother had done . . . one that I had stumbled on serendipitously and then it actually looked, took the shape of a literal tower in that the actual structure of the Wall of Death performance, topped as it is with the canopy on the top, looks at a distance like a tower. It was pretty astonishing—I mean, I did feel like I was struck by lightning at the recognition: that I had stumbled across with random luck, that I was able to call my mother in the US and tell her about it and share it with her. Then later, when I went to really apply myself to the manuscript and I was working remotely in this residency, I had just left my mother home during her last stages of illness, during what would be the last part of her life to attend the MacDowell residency. It had been scheduled with plans to return to her to help in her care and be with her . . . and I knew it was a risk to go because it was time I couldn’t spend with her towards the end of her life, or potentially, we didn’t know, she could’ve been in hospice for two years. It wasn’t cancer or an illness like that, but there were a number of illnesses, great and chronic pain, and an eventuality.

Anyway, while I was in this sort of cloistered situation, a deep immersion powered by great imperative that burrowed in, and, and this is hard to talk about, I often felt the experience of The Tower . . . that sensation, where I would have this—I’m not sure if I explain this in the broadcast because it sounds like quite the conceit—but, did I talk about that movie Amadeus in the Occult Radio podcast?

I don’t think you did . . .

Ok . . . it was a movie that came out in the eighties, I think I must have seen it in the theater—it was a wildly popular film and at the end of the movie, they show a death scene between the two main characters where Amadeus [Mozart] is dying and there’s someone [composer Antonio Salieri] that’s transcribing his very last composition—do you know this movie?

No . . .

There’s this one scene, it sticks out famously in my mind—I don’t know if it’s really truly famous—but it’s kind of a crescendo of the movie where he’s transmitting his most brilliant and final composition to who had essentially been his rival and really caused a lot of problems and was deeply jealous of his talent, and he was transcribing it, and Amadeus Mozart was in sort of the throes of this kind of delirium which is like this transmission . . . An experience of lightning strike, I would be crying and then starting to laugh immediately from my gut with tears coming down my face. Electric: and I realized that is really the tower energy—which connected, I also realized with hexagram 51 of the I Ching which often is given the subtitle as “Shock, Thunder, haha! (Laughs.) Spontaneous events. And then the fortune for this hexagram says that after great shock, it’s time to innovate, after obstruction, it’s time to permeate. Something like that: having to adapt is to have to go into these other modes . . . to decreate or decompose, maybe–and that, ultimately, you’ll get your treasure back.

But it’s all about this kind of convulsive change, and then I realized, Well, of course, that’s exactly the experience that my mother had. The Tower as symbol then took on these other relevancies that had to do with, of course, the architecture of a tower and its crumbling has long been implicated in language itself, right? It’s also a kind of masculine image that’s crumbling, right? So these layers that came out after the images found me—the emblems found me first, or I found them—then they’re the layers of resonances, I was able to comprehend them more as I worked with them and also my experience of writing the manuscript, so I understood that this was the task, that was part of the helping the women.

Wow, that is remarkable, and I did not even think about the tower as this sort of phallic, patriarchal, masculine image that is crumbling . . . Oh!

And also just to clean up one response from earlier, you had asked about the songs and how I slice them, and I really only talked about a folk song tradition . . . The popular song of “Qué Será Será,” which is a kind of timestamp—this would’ve been early sixties, late fifties, when that song was out, but it was circulating in Saigon or Vinh Long—so there’s like a little personal story of her telling me about that song, which isn’t in the manuscript but it just appears as lyrics . . . And then there was a songwriter, a Vietnamese songwriter [Trịnh Công Sơn], who I don’t actually think was important to my mother—I actually asked about him in particular and she didn’t really have a memory of any of the songs when I found and played them to her from YouTube or read the lyrics to her. She was like, No, I don’t know what that is . . . but I understood that he was this important songwriter from Hue who later was described as the Vietnamese Bob Dylan, a reference that is important to her generation in Vietnam. And then of course, he’s a really great lyricist, so that made it attractive to me to have his song lyrics inform the poems.

Well, I also love that you have certain stories that you’ve kept for yourself . . .

Yes, me too. (Laughs.) I mean I even kind of concretize that a little bit in the poems where it’s the translation of a scrap of the newspaper, but even there I don’t tell you what the lucky numbers are . . .

Oh, yes . . . I remember that, and now I understand that! I’m trying to find that poem . . . I downloaded the pdf because I really like to write in my books, so I made a lot of notes on these . . . I think it was one of the ones about the name . . . I will look for it. The Mozart movie that you mention, is it called Amadeus? I’m going to look it up.

Yeah, it’s called Amadeus . . . I would have been in high school when it played in the theaters and I think the movie offered an eccentric example of what it looked like to be a writer, or to be an artist, and here I think it functions as a kind of emblem of the artist as a kind of conduit transmitter—not necessarily in possession of the stories or the music but carrying them and placing them.

That’s one of the words that I wrote at the very top of my notes, you and your work as a conduit.

Yeah, so I think that when I saw that movie, it must’ve been an early example of what I later came to understand as the way in which I think about my own practice . . .

Ok, I’m going to see if I can hop into YouTube after this to find that, I’m sure there’s a recorded fragment of that scene . . .

I’ll try to find it, too! Now I really feel like I need to rewatch this scene because clearly it’s at the front of my imagination. I may be disappointed though when I actually watch it and maybe think, Well, that was a nothing moment . . . (Laughs.)

This does happen. Sometimes what we’ve crafted in our memory banks is far richer than the actual thing it sprang from . . .

Which I think is an important kind of recognition I had around writing these poems, too. There’s memory, there’s inaccuracies, there’s conveniences . . . there’s all kinds of things that I think are part of the telling, and I was interested in making some space for those difficulties even to express themselves. It’s not a straightforward reading, the book.

No, it’s not a straightforward reading, but I don’t think it should be straightforward because these stories are so complicated and, as you said, layered, and have evolutions, or other sides to them that I think have yet to be revealed. I appreciate that it is so nuanced.

—

Andrea Blancas Beltran is a writer and artist from El Paso, Texas. Her work has been selected for publication in The Offing, Borderlands: Texas Poetry Review, Poetry Northwest, Scalawag, and others. You can find her @drebelle.