Interview // “Poems are Considerate Objects”: A Conversation with Claudia Castro Luna

by Paul E Nelson | Contributing Writer

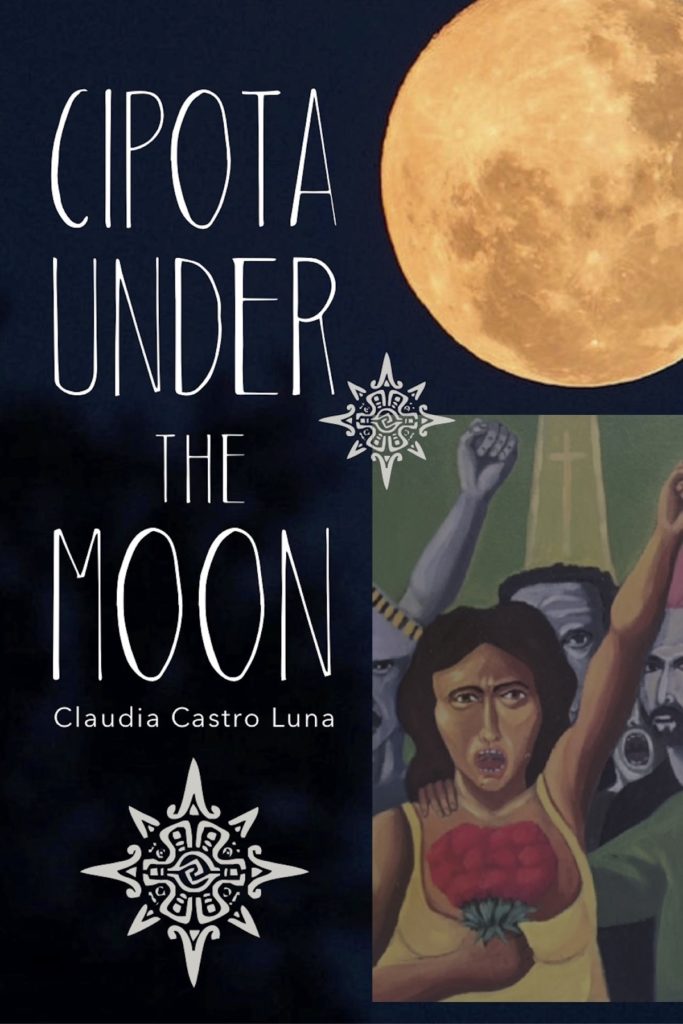

There’s war raging in Ukraine, a general feeling that a second U.S. civil war is possible given the divisiveness of U.S. American politics, AND children being murdered in schools is just “something we have to accept as a free society,” according to 44% of Republicans in a CBS news poll. It’s got to feel like déjà vu to Claudia Castro Luna, a refugee from El Salvador’s civil war in the 1980s. The correspondences are eerie in her new book Cipota Under the Moon, published by Tia Chucha Press. Claudia is a former Poet Laureate of the state of Washington, and Cipota Under the Moon is described “as a testament to the men, women, and children who bet on life at all costs, and now make their home in another language in another place, where they by their presence change every day.” This conversation took place via Zoom on June 17, 2022 and has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Paul E Nelson: Can you tell us about the word “cipota”?

Claudia Castro Luna: Well, cipota is a Salvadoran-to-the-core word that means “girl.”

PEN: You don’t find it in Cuba or Mexico?

CL: No. This is Salvi speak all the way. In El Salvador, nobody says, “That is a niña.” We say cipota, or cipote, and I really wanted the title of the book to cue immediately to any Central American that this was a book about that region. Hondurans also used the words cipote and cipota. It already positions the book in a sociohistorical and geographical space. “Cipota Baja La Luna” is the name of a blog I started eons ago, and I’ve written in it intermittently over the years. So the title of the book is essentially the title of the blog, but in English.

PEN: This is a very personal book.

Yes, it is. It’s the most personal of my books actually.

PEN: Why now the time to dig into that?

CL: You know, that’s an interesting question, Paul. I wrote the book largely during the pandemic, although many of those poems have been written over the years and never published—we all had those moments during the pandemic where we had time in our hands, right? I started looking at this unpublished work and realized that there was an arc there, and there was a book there. There were things missing for it to be a full collection, so I started writing into those missing spaces. And that’s how the book came about.

PEN: That was going to be my next question. Some of the poems go back to 2009, and the question I was going to ask was, “How do you assemble a book?” But you just told us. You see these poems, you have some time, and you fill in the gaps by writing. Is that a typical way that you would write a book?

CL: No, but it makes me think—and I’m saying this because I know you’re a fan of Denise Levertov, if I remember correctly—that Levertov would write and edit, and when the poem was done, it went into a pile. And eventually there were enough poems there for a collection to come together.

That is not how I’ve written my other books at all. The other books have been more project-driven. I’ve had an idea and I’ve really written into that for a period of time. These poems are different. There’s different styles and different expressions because they spread over such a long period of time.

One of the poems toward the end of the book, “My Father’s Garden,” is the first poem that I ever published. I think that’s the one you’re referring to. And it makes sense in the context of the book to have that poem there: it’s about the war and my dad, and my father’s return to El Salvador. My father’s a huge gardener, and plants and the natural world have helped him—and me, too—cope and deal and, to an extent, transcend the muck of the experience of living with war.

PEN: Nature has a very healing capacity, obviously. The background of writing that particular poem may give us a sense of your evolution as a poet. Can you speak to that?

CL: I’ve been writing all my life, but I think I never wanted to take it up seriously. I always wrote poems. That was my default. When I wrote, if anything came out of me, it showed up as a poem. And there was a point when I was already a mom, and I had two of my three kids already and realized that I really needed to pursue poetry. So I started taking classes at a community college. So that poem was written in this community college classroom in Oakland. And I remember my husband reading this poem, and then he looked up, and he said, “You wrote this?” And I said, “Yeah, I wrote it. You know, I mean, I don’t know where it came from, but I did. I wrote it.”

I remember the professor handing back poems to everybody in the class, and then talking to me on the side, and saying, “Claudia, would you come to the open mic and read this poem at Laney College in Oakland?” I’d never heard of an open mic. I had no idea what it was. And then he explained to me, “We get together once a month. It’s an open reading to the college community and to the city in general. Anybody can come. We do it in the auditorium. It’s super fun. You should come. I’d love for you to read this poem. And I want you to submit it to this publication.”

And so I agreed to the submission. I hesitated on the reading because it just seemed terrifying to me to read in public. But I went, I showed up, and it was like Hugo House used to be, where you stand up on this stage and you cannot see anybody. Everything is so dark and you have a light on your face. And I don’t even know how I got through reading it.

I read the poem and it was such an incredible experience, particularly to see it printed later in a magazine. They threw a small publication party. And I was there again, and I read the poem again. And just that this experience that could be shared in this fashion with others was really amazing. That has been my trajectory. I took a lot of community college classes. And eventually I realized this is not going to go away. I need a lot more than evening classes could give me. And so I gave up my job and went and did an MFA full time.

PEN: Where?

CL: At Mills College.

PEN: Right there in Oakland.

CL: Right there in Oakland. By then, I was a mom of three and I couldn’t travel to a different place to do an MFA. So I applied to three local MFAs and chose the one at Mills.

PEN: I’d like to discuss a couple of other poems, brutal poems, closer to the beginning of the book. “Dios Madre” is especially haunting. It may not be seen as a compliment, but I get a nauseous feeling when reading that poem. I mean, I think of my little girl, about the same thing happening to me. And the empathy is yours. It’s one of your talents as a poet. And the touch of magical realism takes us out of “this is an elegy, this is simply sentiment.” It adds so much to the poem when you go into that moment of the father, whose daughter has been murdered, cutting his head off and carrying it around. Can you tell us about the background of the poem and maybe how that surreal element comes into your work like that?

CL: You know, that’s a true story. This is my father’s town, where he lives. The tree that I refer to is in front of his house. There were children playing on the street and a gang fight broke out and the girl was killed directly in front of my dad’s house. I mean, you opened the door and there’s the tree. And there she was in the middle of the street. And her family owned a little pulperia, a little store, a tiendita on the corner.

I went to visit my dad and there was a photograph of a little girl in the frame, in a kind of a homemade frame. Then I went to my aunt’s house, also in the same neighborhood. And there was the little frame with the girl. And this girl is not a relative. I never had seen her. So then I asked, “Who is that little girl, who’s in that frame?” Then they told me the story. My dad said that one of the first people who saw her was his wife, because they heard the gunshots. When they ran to the street and she opened the door, there was the girl. So that was just so . . . it’s impactful in the poem, but just to hear them tell me the story and watch them break down because they knew this little girl . . . She lived in the neighborhood. Kids play on the street, right? Still to this day, as I did as a kid.

I really wanted to focus on the lasting damage to kids. And also to the way in which their suffering is really the unintended, or maybe intended, byproduct of these wars and this violence. There are several poems in the book about fathers. I write about fathers and the relationship to children, because I think it’s necessary to showcase different ways of parenting, different ways that men could be fathers. I mean, this dad was heartbroken over the death of his child and he in fact, fled, as the poem says. It’s true. He fled to the U.S. He could not imagine himself in this town without his kid. He was just so heartbroken from grief that he needed to be in a place where no one knew him in order to be able to carry on with his, with his day, with his life.

There are Latino men who are caring and loving of their kids. For me, I really want to focus on other ways of portraying masculinity getting away from destructive stereotypes.

The magical realism piece that you picked up on comes from reading the Popol Vuh. There is one moment in the Popol Vuh where the twins go down to the underworld and defy death. One of them is decapitated, but the other one figures out that they could fool death by giving him a head made out of a pumpkin. And pumpkins, of course, are so central to the diet of the Mayans: corn, beans, and squash.

They defy death with this ruse, and they are able to go, then, back into the world. And then the world begins. Once they have done and achieved this, the world begins. For me, the father is going through hell. So the father is in an underworld and he’s traveling in the same way in which these twins travel.

It is my wish for him that he find himself in a different place, in a different way, where he could still hold his grief and move on with his life. So that’s the piece when it does enter into that moment where he cuts his head off, and just moves through hell.

PEN: Is it the Dennis Tedlock translation?

CL: Gosh, I have several. I don’t know which one I was reading. I think I was reading an annotated version that my dad sent me from El Salvador. It’s in Spanish, the one I have. So I have them in translation, and I also have it in different versions in Spanish.

Somebody asked me recently, what books would I not part with? And I thought, “Wow, that’s a tough question. I don’t like that question.” But then I thought I would not part with my different versions of the Popol Vuh.

PEN: There are a lot of prose poems in this book. What was the inspiration to start writing in that way?

CL: Well, I’ve been writing prose poems for a long, long time. I didn’t know about prose poems. I thought all poems were open verse. Or verse, right? Metered poems. Well, then when I got to Mills, I discovered that you could write prose poems. I read Baudelaire’s poems, read Les Fleurs du mal and Bashō’s haibun.

I’m really drawn to prose poems whenever the expression requires a form that can carry a story. And I like their propulsiveness because we’re reading across as we read a regular text. The eye can move really quickly and in a very natural way across these lines that propels them forward. There’s a movement embedded in the form that I really like.

PEN: When I read the poem, “Monseñor Romero,” I think of Archbishop Óscar Romero. And the Father Bill in the poem, I think might be Father Bill Bichsel, the activist Jesuit priest who served prison time for his nonviolent resistance against the School of the Americas, among other things.

CL: This was Father Bill O’Donnell, who was a priest in Berkeley at Saint Joseph the Worker Church. Actually, a Jewish friend of mine said, “You go check out Saint Joseph the Worker,” because he played the trumpet there sometimes. And I thought, “If this person who is Jewish is recommending this Catholic church, I’m going to go check it out.”

I met Father Bill, and I then became a member of the congregation. My father was a Marxist growing up. So there was no first communion for me when I was little, but it’s something I always wanted to do. At that time, I only had my first kid, I went through the process of becoming Catholic, and Father Bill was the person who oversaw that.

He was an incredible person. He was an incredible individual. When I walked into the church, the cross at the front of the altar was one that had been made in El Salvador in this particular style from northern El Salvador, from a town called La Palma. It’s just so recognizable. When I saw it, I thought, Oh, I don’t think my friend could read that, or know that. He just knew Father Bill. But the cross was there in that church, on the altar and it really drew me. I knew there was a strong connection there beyond words. I was meant to discover this place.

When Father Bill died, I was expecting. I was really, really pregnant, and I just could not stop crying. They had a service at the Berkeley High School auditorium, which is a huge auditorium. Nancy Pelosi was there, because she is a rep from San Francisco, and Father Bill was known in the whole Bay Area. So there were politicians, union leaders—I mean, it was just overwhelming.

I was sitting next to this woman and I just wept. I wept for two days. I turned around to this woman and I said, “I’m sorry. I just don’t know why I cannot stop crying.” But I realized, as the poem says, that when Monseñor Romero died, I was in El Salvador. My family was in El Salvador, and there was really no room for grieving. There just wasn’t. It was too scary. It was too disruptive.

So then Father Bill, who was so close to El Salvador, by the time he died—he died typing his homily. He had a heart attack and collapsed onto his typewriter with Monseñor Romero’s sermons on the side of the typewriter.And so when he died, it was like this flood of sorrow, this gate that just went open. I was both grieving Father Bill, but I was also grieving the grieving that I could not do all those decades earlier.

CL: He was going to baptize my oldest kid. All three of them were baptized at Saint Joseph the Worker in Berkeley. But he had been arrested so many times at School of the Americas that he was made to serve time in prison, as old as he was. The baptism was slated to happen and then he was away in prison. I could not believe that they would demand that he serve time as old as he was.

PEN: Oh yes. And it says something about a culture that would do something like that, would put a man like that in prison for more than a 24-, 48-hour period. It’s the same kind of culture that would create a School of the Americas in the first place.

CL: Absolutely. Yeah.

PEN: And for those who don’t know about the School of the Americas, Google it, and see what your tax dollars have been going for, which is really horrible. Tell us about the use of Spanish in the book. This is a new development, yeah, to include a lot of Spanish?

CL: Yeah. You know, the publisher had remarked on that. He said, “Spanish shows up so much that it’s just part of the work.” I think two things happened with these poems. In some poems I didn’t even know when I crossed over to Spanish. I was writing and there it was. So to have changed them would’ve been a little betrayal of the poem itself.

I wanted both languages to exist on the same plane. I didn’t want any kind of translation or italicizing the Spanish. I wanted them to be side by side because that’s how they showed up. That’s how they live in me. That’s how they exist in myself. Poems are artifacts that come before language. They’re forms. We give them form through language, but the poem is before any kind of word whether it’s English or German, or I don’t know, Mandarin, that you end up putting on the page, that is the form.

PEN: I’m reminded of that when I read “Aguacatero.” You’re excavating this experience that you didn’t really get a time to grieve when you were fourteen, and since then, has caused you health issues. You left Salvador and came to the country that aided and abetted the side with the overwhelming number of civilian killings and human rights. That’s according to the U.N. Truth Commission on El Salvador. Tell us about what writing a book like this allows you to accomplish in your own relationship with all of this. Writing about this at some cost to your current health.

CL: Yes. Yes. True. You know, Paul, I’m glad I persevered with the poems because there isn’t enough written about the experience of Salvadorans and why there’s four million of us now in this country. 80% of people in El Salvador—professionals, university students—agreed that there needed to be radical changes to healthcare, to education, to land reform. It was a frustration. You could see the poverty. You could see the poverty on the streets and how it affected us all.

I think it could have been resolved so much quicker and with far less death than it did, had the U.S. never gotten involved. Because that refocused the struggle, which was one for human rights, essentially, to one about the Cold War. Reagan positioned and justified the aid by saying, “The Soviets are going to find fertile ground in Central America and the Caribbean, and we need to do everything possible not to have a Soviet presence in our backyard.”

The struggle was one for human rights. I mean, I was there. I could tell you. I had classmates that showed up with no shoes at school. My parents were both teachers struggling with things like healthcare. Just basic human needs, right? And horrible repression where people were being killed and jailed and murdered. And there were secret jails where people were disposed of in ditches, this before the war officially became the war.

And so all of those human rights violations were ignored in favor of this made up evidence to justify this rhetoric of the Cold War for the U.S.. And so it spun everything out of control to the point that to me, the people leaving El Salvador this day, right now, coming to the US, are escaping that devastation that the war left. So for me, this war never ended. My family was incredibly lucky to have been able to escape very early in the early years of the war. And even having escaped as early as we did, it was still devastating. And I’m still, like you said, suffering the repercussions of the war in my body.

I’ve been hospitalized due to writing these poems and working on other prose pieces about the war. So it’s really, really important that people understand how this war came about, and the implications of the United States. And it’s important for us Salvadorans in the U.S. to have some documentation of the war. That is really what drove me to write new poems. There’s one poem titled “Caravans” at the beginning of the book, which is about precisely that. About how the bullets that were dislodged in 1982 are still finding their way to find victims now. All these decades later. So, yeah, I think Héctor Tobar has a statement in the back of the book that this is a documentation of this tragic history of El Salvador and Central America. And that was really what propelled me.

PEN: Has the war come home, here?

CL: I think so. Yes. The war came here many ways. In the 1980s and early 90s, I remember being at a party in L.A., and somebody said there were soldiers there. There were people who fought on the government side, and suddenly we found ourselves on the same plane. That happened a lot. In that sense, the war has come home. In the middle part of the book, I also draw a parallel between the war that we live with now. Those kids in Uvalde, that’s a war. That’s devastation that happens in a war situation. How about the killings of the people up in Buffalo? Same thing. We escape war only to find another war.

I work in this book to show those parallels between the war in El Salvador that my family escaped and the war that I find myself living here in the U.S. When I think about the Pacific Northwest, I feel very much at home here, and part of that is that I live with less stress. I live with fewer triggers. Where I am at this moment, I’m surrounded by trees. My body rests from all the ways in which it gets triggered back to those moments.

PEN: You’ve been out of the Washington State Poet Laureate position for over a year now. What do you think is the role of the poet in a materialistic society that doesn’t value poets? I remember I put a flyer that I was playing with a jazz trio at the Ethiopian restaurant in the mail room, and a neighbor said, “Oh, I missed your gig.” I said, “Well, I got another one coming up.” I had the book launch at C & P coffee house. And he came and didn’t say much and left at the break. And I said, “Hey, how’d you like it?” And he said, “Well, we thought you were a musician. We were going to hear you play. And when you started reading your . . .”—he didn’t say when you started reading your awful poem—”. . . so we knew we were in more than we bargained for.”

What is the role of the poet in a materialistic society? Are the poet laureate positions that we have around this country doing anything for poetry? Or is there a higher calling? Is there a higher role? I think the work that you’re doing with this book, witnessing, is the highest calling of the poet.

CL: When I was traveling around the state, people always asked, “What’s a poem? What’s a poem?” I think that people sometimes put too much pressure on poetry to solve all their ills. I also think that poetry is the opposite—the complete opposite—of the crappy news cycle that we’re in. In order to write a poem, you really have to consider and wait. You have to weigh each word. Poems are considerate objects. If it’s going to be a good poem, a solid poem, you have to think about it. You have to consider, not just say lies. Not just say things and throw things on the page.

It’s important to show a different way of engaging with language. I think that poets and sharing poetry in spaces that are unexpected, which a laureate often has to do, is a way of having moments to consider that. I think it’s important to create spaces to resist and for poetry to continue existing, even when—as you said before—we get very small audiences. I remember reading once in Port Angeles, in a downpour, it was a miracle that four people even showed up. And then again, there’s other times when you have a lot more people come to a poetry reading, but both are equally necessary and important. It’s necessary and important to be out there holding that space.

Because the moment we give up showing a different way of being with language and the imagination, we have lost. It would be like there’d be no flowers anymore in the world. You know, the Mayans and indigenous people in Guatemala and El Salvador, poetry is floricanto, right? That is the translation into Spanish. Flower and song. And flowers, when you read the Popol Vuh, flowers are the highest expression of divinity. They were revered, flowers. We love them now of course, but in the Popol Vuh there’s such a reverence toward blooms. Having a world without poetry would be the equivalent of not having flowers in the world.

—

Claudia Castro Luna is an Academy of American Poets Poet Laureate fellow (2019), WA State Poet Laureate (2018 – 2021) and Seattle’s inaugural Civic Poet (2015-2018). Castro Luna is the author of Cipota Under the Moon (Tia Chucha Press, 2022); One River, A Thousand Voices (Chin Music Press); the Pushcart nominated Killing Marías (Two Sylvias Press), also shortlisted for WA State 2018 Book Award in poetry, and the chapbook This City (Floating Bridge Press). Her most recent non-fiction is in There’s a Revolution Outside, My Love: Letters from a Crisis (Vintage). Born in El Salvador she came to the United States in 1981. Living in English and Spanish, Claudia writes and teaches in Seattle on unceded Duwamish lands where she gardens and keeps chickens with her husband and their three children.

Poet & interviewer Paul E Nelson is the son of a labor activist father and Cuban immigrant mother. Born on Chicago’s west side in 1961, he’s lived in King County since 1988. He founded the Cascadia Poetics LAB (formerly SPLAB) and the Cascadia Poetry Festival. Since 1993, CPL has produced hundreds of poetry events & 700 hours of interview programming with legendary poets & whole systems activists, including Allen Ginsberg, Michael McClure, Joanne Kyger, Robin Blaser, Diane di Prima, Daphne Marlatt, Nate Mackey, George Bowering, Barry McKinnon, José Kozer, Brenda Hillman & many others. Paul’s books include Haibun de la Serna (2022), A Time Before Slaughter/Pig War: & Other Songs of Cascadia (2020), American Prophets (interviews 1994-2012) (2018), American Sentences (2015, 2021), A Time Before Slaughter (2009), and Organic in Cascadia: A Sequence of Energies (2013). He is the co-editor of Make It True: Poetry From Cascadia (2015), 56 Days of August: Poetry Postcards (2017), Samthology: A Tribute to Sam Hamill (2019), and Make it True meets Medusario (2019) (a bilingual anthology in Spanish and English.) He’s presented poetry/poetics in London, Brussels, Nanaimo, Los Angeles, Qinghai & Beijing, China, has had work translated into Spanish, Chinese and Portuguese, and writes an American Sentence every day.

This interview is available via the Cascadian Prophets podcast, hosted and produced by Paul E Nelson via the Cascadia Poetics Lab, and on YouTube.