Close Reading a Visual Poem and Two Poetry Comics

by Gabrielle Bates | Editorial Assistant

There are some fabulous interviews out there with poetry comic artists (I’m a big fan of this roundtable over at the Rumpus), and for those in search of a preliminary orientation to comics poetry in general, Alexander Rothman’s manifesto offers some helpful arguments. However, when I cast my line out for close readings of contemporary works of visual poetry and poetry comics, I reel in much less than I’d like. This being the case, I’m grateful for the opportunity to think aloud about a few of the dazzling works of visual poetry and poetry comics published in the Winter and Spring 2018 issue of Poetry Northwest. My love for these pieces increases the longer I stare at them, think through their arguments, and wrestle with their choices. I wish I had the time and space to write an essay on the work of all ten artists, but as it is, what follows is a brief overview and rumination on three.

These three pieces come from artists whose work I’ve been following for a while now, and whose art and ideas have had profound effects on my own life as a poetry comic artist. I was drawn to these artists, in part, because I was interested in how these new works fit in the context of their previous work. They also, in the order I’ve imposed on them here, hint at a continuum (between poetry and comics), beginning with Catherine Bresner’s text-forward “American Sentence,” which looks more like a poem than a traditional comic; followed by Colleen Louise Barry’s “Bye,” whose surreal visual and textual elements blend and juxtapose into mysterious wholes; and ending with Bianca Stone’s “Possible Pig / Breakfast,” a character-forward piece with panels, which looks a lot more like a comic than a traditional poem. My hope, with this sample and this order, is to hint at the varied and expansive quality of the poetry comics mode at large.

Although you’ll find excerpts here, I encourage you to pick up a copy of the issue and see for yourself the full range of these and other artists’ hybrid visual-and-textual work. When viewed together in the magazine, certain shared preoccupations and influences make themselves known, some of which will be discussed here. Many take up the exhausting and perplexing relationship of humans to other humans, and several either directly or obliquely reference the last U.S. presidential election. A number are in conversation with Gertrude Stein. There is a recurring obsession with the poetic line—as a defining unit of poetic language, yes, but also as object, barrier, directive, backdrop, un-language. Most exciting to me, perhaps, we see artists willing to take risks and experiment, to push themselves in new directions.

*

“[A] sentence,” says Gertrude Stein, “should force itself upon you, make you know yourself knowing it.” Almost a century later, Louise Glück pens, “Contemporary literature is… a literature of the self examining its responses.” If there is truth in both claims, and I think there is, then Catherine Bresner’s “American Sentence” holds a mirror to the mirrors that define our current moment in American poetry.

The violence and meta-cognitive properties Stein attributes to a good sentence when she says it “should force itself upon you” and “make you know yourself knowing it” play a crucial role in Bresner’s visual poem, lending a central tension that both propels the reader forward and bids them tread with care through the architecture of lines, dots, and language on the page. In other words: these are good, forceful sentences.

But they are more than that. Minimalist as blueprints, the sentence diagrams’ shapely notations evoke the etymological roots of “stanza” as “room”—reminding us, even while abstracting language to its orders and parts of speech, that poetry is something we navigate as a body navigates a physical structure. We are moved from room to room, vulnerable to what the creator has in store. To me, the structure of a poem has a lot in common with that of a haunted house, and Catherine Bresner’s hand-written, hand-drawn diagrams encourage us to see “American Sentence” as a haunted house in its early stages of construction. There is an aura of incipiency here. This is a preliminary blueprint, before the structure’s plan has been digitized and finalized, before it has actually been built.

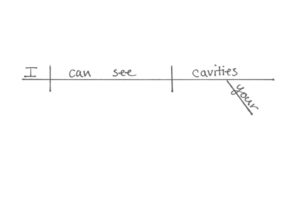

The occasion of “American Sentence” is a Tuesday night. The female speaker sits down to dinner with a menacing man, and the television is on. As the election results come in, the speaker directs a statement of observation at her white male counterpart (“I can see your cavities”) and then asks, in the next diagram, “Are you looking at my cavities too”? The reflexive swerve toward the self feels—in light of Glück’s statement—utterly contemporary, utterly American, a natural progression for a mind examining its articulations as they’re articulated.

Sentence diagramming, in general, recalls a time of grammar instruction. In a poem written in English about—among other things—the last presidential election in the United States, I can’t help but see connections between this poem’s evocations of “learning proper English” and the rhetorical treatment of immigrants and refugees during and after that campaign. Perhaps, in this light, the sentence diagram form is indicative of a core impulse: the poet—a white-presenting English speaker—wanting to make herself know herself in the wake of an election where 52% of white women cast their votes for Trump, a candidate for whom, due to the poem’s overall air of menace and toxic masculinity, we can assume the speaker did not endorse. It makes sense that at such a time, this particular speaker would look in the mirror and see the enemy, that she would examine her response to herself as such, and that the haunted house she sketched would be built in her image.

I’ve long admired Catherine Bresner for her sharp critiques of power and the formal experimentation she employs to do so. Whether she’s turning her eye to the physical and psychological effects of living in a culture of violence against women in her digital collage poetry comic “January 2nd” or to dismantling white supremacist ideas in her embellished erasure “Bond Voyage,” this poet is not afraid to take to task the powers that be. Furthermore, I don’t think I’ve ever seen her work in the same medium twice. Pen-and-ink drawing, glossy magazine collage, erasure, sentence diagramming —“American Sentence” is only the most recent in what is sure to continue to be a deliciously varied career.

*

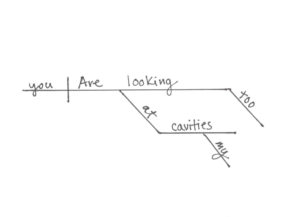

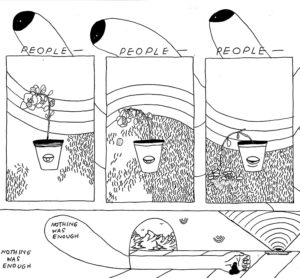

In the poetry comic “Bye” (available in its entirety online), pattern and repetition serve as the scaffolding through which Colleen Louise Barry drapes and weaves her trippy surrealism. Cyclopic eyes—scattered like fried eggs on the ground, stuck heavy-lidded onto flower pots—reappear across panels, as do flowers and disembodied arms. Textual repetition also plays an important role, reaching a crescendo in the piece’s final panel, which reads “PEOPLE— PEOPLE— PEOPLE—” accompanied by the image of a wilting cyclops orchid, and below that, “NOTHING WAS ENOUGH,” repeated twice: once floating freely, once contained by a bubble.

If Catherine Bresner’s sentence diagrams are blueprints for a haunted house, Colleen Louise Barry’s poetry comic is the first-person footage of a body tripping through it. We push with the protagonist through a wall of flowers, face the mouth of a tunnel, experience a barrage of hallucinatory stimuli as we walk forward, then collapse with our arm in the tunnel, unable to go any further. This poetry comic may be, in many ways, about feeling exhausted, but it’s also manic. Compositionally, the panels are artfully busy, layering panels, landscapes, and patterns. Barry sends text scooting up walls and around corners, pulls it from the mouth of mouthless and mysterious sources: roses, a watch, a hooded guru. Reading this poetry comic, we become its “people inside the garden.”

In her work, Barry often blurs boundaries—not just between text and image—but between reality and dream, inner and outer, human and inhuman, we and I. The only noticeable difference, in fact, between “Bye” and other work of Barry’s I’ve had the pleasure to see is in its lack of color. The unshaded black-and-white drawings in “Bye” have a flattening and equalizing effect, allowing for the intentional affront of this comic’s surreal world. While the movement is of its images palpable, the scenery is rendered in two dimensions, and this kind of sensory contradiction keeps readers on their toes. Perhaps because I’m used to seeing Barry’s work in color, the unshaded black-and-white quality also calls to my mind a coloring book. It’s as if, when the speaker collapses onto the tracks in the final panel, they’re unable to get up and color in all that they’ve drawn. I can almost hear them saying, exhausted, “You do it.”

The comic’s title, enclosed in quotation marks in the opening panel, frames the comic as a departure, a journey. That journey is short and yet, chock-full of stimuli, it drains its hero into a slump. Reading this comic again and again gave me much the same feeling as watching a gif: the circularity of the experience works in tandem with the comic’s strategy of overstimulation and its tone of fatigue, evoking—along with the visual and textual repetitions—yet another thrilling and unbearable endlessness.

*

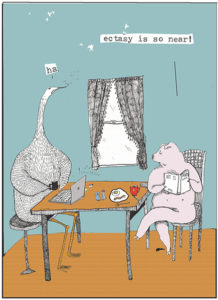

The work of Bianca Stone—published in such places as Poetry and in her book Poetry Comics from the Book of Hours—introduced many of us to the concept of poetry comics for the first time. Here, her four-panel, single-page comic “Possible Pig / Breakfast” both continues and departs significantly from her previous work. Where once her palette was dark, her images smeared with black ink, populated with human nudes and exploding heads against precarious and debaucherous backdrops, we find here muted pastel colors, neat lines, clean domestic settings, and a marked absence of the human.

I typically steer away from using autobiography as a lens, but it seems significant that in the time between creating Poetry Comics from the Book of Hours and this new work, the artist has become a mother. While there is no mention of motherhood in “Possible Pig / Breakfast” nor the presence of any form of child, there are many ways in which this poetry comic calls to mind traditions of children’s literature: animals acting like humans, for example, and clear representations of positive and negative behavior.

Whenever I give talks on poetry comics at schools, I typically use children’s literature as a launching off point for discussing the different ways in which visual and textual modes can interact. On the children’s literature side of the spectrum, the visual and the textual often support or illustrate each other, while on the poetry comic side of the spectrum, the visual and the textual often contrast, juxtapose, spar. Overall, Stone’s new work feels more like a hybrid of traditional comic and children’s literature than her previous work; however, there are still surprising movements and poetic language, and the concerns (American politics, emotional perspective) are certainly adult.

The two main characters and speakers of “Possible Pig / Breakfast” are a pig and a large bird. Their presence at the breakfast table tells us that they live together, and the comic’s formal qualities, the characters and their setting, as well as their conversation all present us with many oppositional dichotomies clearly divvied into bad and good:

|

Bad, as represented by the bird |

Good, as represented by the pig |

|

Digital Media (laptop) |

Physical Media (book) |

|

Breaking News (Trump) |

Literature (poetry) |

|

Angsty Pessimism |

Serene Optimism |

|

Seeing |

Listening |

|

Black-and-White |

Color |

The oppositional dichotomy I’m most intrigued by in this comic is the one I see as its least intuitive: seeing < listening. “Close your eyes and listen hard,” the optimistic, poetry-reading pig says, when the smoking bird scoffs at the idea that “ecstasy is so near.” Seeing, the pig argues, separates or distracts from ecstasy. I’m reminded of the open eyes splattered across Colleen Louise Barry’s poetry comic “Bye,” forced to stare at the bizarre and overwhelming world until they droop. An excess of visual exposure, both of these poetry comics seem to say, is harmful, antithetical to true joy. I find it fascinating to see these artists critiquing words and images, their own methods of meaning-making. In fact, all three artists—Catherine Bresner, Colleen Louise Barry, and Bianca Stone—display in these pieces a distrust of the vehicles—namely, language, images, and the self—on which their art depends.

Though distrust and ill ease is palpable in much of the art created over the past year, and these three pieces are no exception, this work does not leave me feeling helpless or paralyze me with negative emotion. Much to the contrary, I find myself reminded—as Bianca Stone’s pig character says—that despite all there is to despair about, ecstasy exists, art can still thrill, poetry in its endlessly varied permutations retains the capacity to soothe. By tackling disgust, fear, and exhaustion with such surprising, intelligent craft, these artists have punctured me in such a way that I feel some of the disgust, fear, and exhaustion leaving my body for the first time in a long while.

—

Glück, Louise. “American Narcissism.” American Originality: Essays on Poetry. FSG. 2017.

Steenson, Sasha. “With Pleasure: Gertrude Stein and the Sentence Diagram.” Taos Journal of International Poetry & Art. 2017.

Stone, Bianca. Poetry Comics from the Book of Hours. Pleiades Press. 2016.