by Cody Stetzel | Contributing Writer

Eccentric Days of Hope and Sorrow

by Natalka Bilotserkivets (translated by Ali Kinsella and Dzvinia Orlowsky)

Lost Horse Press, 2021

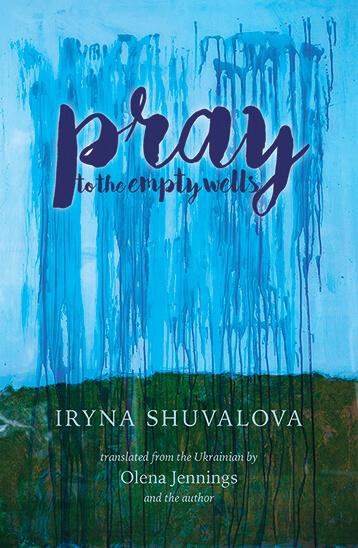

Pray to the Empty Wells

by Iryna Shuvalova (translated by Olena Jennings & Iryna Shuvalova)

Lost Horse Press, 2019

Survival is a concept, borne of a need for communication, that must emerge only after threat has already permeated a group’s understanding of itself. Though, conceptually, survival certainly predates communication, individual survival instincts and the group dynamic of staying alive together produce distinguishable communicative needs. Even so, group survival must have evolved from necessity (“I need you all to survive so that we can continue to survive,”) to desire (“I want you to survive,”) to the emotionally distant, imperative form of plea (“You must survive!”). In times of war, the range of emotional states needed for survival seems to slide along this spectrum freely. Need, desire, and pathos purvey instinct as fields of sunflowers are eradicated and the futures of lineages are jeopardized. Art is made to convey this discontinuity to one’s history. Natalka Bilotserkivets’ Eccentric Days of Hope and Sorrow translated by Ali Kinsella and Dzvinia Orlowsky, and Iryna Shuvalova’s Pray to the Empty Wells translated by Olena Jennings and the author herself, both speak to the varying, multiscalar states of the need to communicate survival.

Survival as an effort against discontinuity demands the reader to deconstruct meaning and identity formations, to rebuild it all at the quantum level. Iryna Shuvalova introduces a more conflict-oriented message and theme with her poems, such as the bold declarations the speaker makes in “conversations about war but not only,”

a poet is a hybrid creature, and poetry is a balancing act

between words and things, between facts and lies

but there is no need to make up some stories, when right

in front of you is history

staring you straight in the eyes

Shuvalova navigates the dimension of survival that is both ongoing and after. This line above–“when right/ in front of you is history/ staring you straight in the eyes”–forces me, as a reader, to contend with the fact that, sure, these are excellent writers who are capable of profundities and world-expanding prosody but in my seat, from my readerly distance, I must understand that they are written with a backdrop of horror. For example, I think of Bilotserkivets’ “Red Railcar,”

Don’t be afraid

it’s just a breath just a moment

just a train speeding

up into the mountains

How when I first read Bilotserkivets’ poem, my fondness for the coastal Amtrak train from California to Seattle that will speed up mountains was what first came to mind before I had to near-erase that fondness to understand that, no, this train is a speeding demon, one promising death and destruction. These associations torrent in ways that can only be described as rhizomatic–infinitely collapsing and connecting.

I’m not sure if it’s cliche at this point to reference Deleuze and Guattari’s A Thousand Plateaus, or at least tacky, but speaking about survival compels me toward a particular moment in their theory of the rhizomatic:

The one who is tortured is fundamentally one who loses his or her face, entering into a becoming-animal, a becoming-molecular the ashes of which are thrown to the wind. But it appears that the one who is tortured is not at all the final term, but rather the first step before exclusion. … The rite, the becoming-animal of the scapegoat clearly illustrates this: a first expiatory animal is sacrificed, but a second is driven away, sent out into the desert wilderness. In the signifying regime, the scapegoat represents a new form of increasing entropy in the system of signs: it is charged with everything that was “bad” in a given period, that is, everything that resisted signifying signs, everything that eluded the referral from sign to sign through the different circles.

That is why power centers are defined much more by what escapes them or by their impotence than by their zone of power. In short, the molecular, or microeconomics, micropolitics, is defined not by the smallness of its elements but by the nature of its “mass”—the quantum flow as opposed to the molar segmented line. The task of making the segments correspond to the quanta, of adjusting the segments to the quanta, implies hit-and-miss changes in rhythm and mode rather than any omnipotence; and something always escapes.

A Thousand Plateaus takes the idea of the rhizome as its founding principle and looks at the infinite interstices of influence upon any particular structure or line of understanding. If we take survival as the structure in scrutiny, we can look at it from the effects of individual perception (singular, multiplicity, need, desire, emotional), of materials (food, shelter, weaponry), of micro-activities (fleeing, rebellion, subjugation), or of macro-activities (territorialization, annexation, peacekeeping, trade).

With this in mind, first, we might discuss whelming: the activity of processing the terror-stimulation of explosions, destruction, and death. Bilotserkivets and Shuvalova are excellent to be paired to consider the Ukrainian poetic response to the contemporary crisis of war and its aftermath, and again war. Bilotserkivets’ poetry seems to follow the survival observations of the self and its immediate communities, whereas Shuvalova’s considers the broader contexts of what will happen to one’s town, one’s country, one’s lineage. Above, Deleuze and Guattari bring in the quantum interstices of everything; here, I imagine the applications of quantum hydrodynamics in vortex lines–regions of turbulence that enable multiple connections and terminate at boundary layers.

If the tenets for ‘normalcy’ in a psychic self are security, intimacy, and trust, among others, we can use these as boundaries for the quantum dynamics of survival. A multiphysics of survival. I think of “May,” by Bilotserkivets, wherein she writes,

Yes, we survived that spring,

until recently, weak

school children appeared, milk damp on their lips,

poets who no longer hurt—

We, passive, inert, and others put out the fire,

the reactor’s red heat;

we in our white robes holding dosimeters,

in police epaulets, in military uniforms,

young pregnant women and girls

with children unborn

victims and rescuers,

in the hot heart of Europe.

In this poem, everyone shares the identifiable boundary between school children, police, soldier, and pregnant women so long as they are bracing themselves against “the reactor’s red heat” or “the hot heart of Europe.” Meanwhile, as I write this, the world undergoes a heat wave that is unparalleled in recorded history giving heat an especially terrifying new dimension, the metaphorical sense of heat–a stressor, a precursor to explosion, that which causes weakness–here marks the boundary between survived and yet-to-survive, provides a temporal dimension. She continues this summary in the poem “When I was a student of the university,”

Officials, officialettes, gossips,

gray-nosed typists; pious

preached words; boundless feats

don’t interest me. Ashes

fly around them, and

I have nothing to say.

Here the tension of heat is found in the images of “Ashes / fly around them,” that-which-has-burned-and-could-still-burn-again. But Bilotserkivets does not stay in the limited, liminal scope of self/selves for long, with the poem, ‘Nature,’ serving as an exemplary transitory moment, “Here, our overwhelmed breaths. / The red vixen fled; / the fallen leaves died. / Here, we loved” the past and passive implications providing the backdrop for survival.

If the full scope of survival must include the precursor threat and stressor, then implicitly it must also include the processing that comes after, the neutral acceptance of fate that war is occurring, that death is happening, that one may die or one’s treasures may be eradicated. I hear this argument resounding through Bilotserkivets ‘Red railcar,’ referenced above and completed here,

Don’t be afraid

it’s just a breath just a moment

just a train speeding

up into the mountains

it’s a train

a lonely game a short dream

a railcar stopped in the mountains

a small mistake underlined in red

Here, we can see two shifts in the game of survival–the first is in velocity, and the second is in metaphor. Whereas when the scope of survival is limited to the self and alignment between the individuals involved, the speed by which you are surviving is a floating pace, “Ashes / fly around them,” “the fallen leaves,” notably slow by comparison to “a train speeding / up into the mountains.” And in metaphor, previously the poems were drawn to “boundless feats,” “reactors,” and “hot hearts,” now we are thrust into the active scene of “a railcar stopped in the mountains / a small mistake underlined in red.” I especially love this move, a small mistake is such a wonderful way to zoom in and minimize what previously had been untenable, unscalable. Continuing with the image of the train, ‘Metro Train,’ the poem adds on,

people droop—

shriveled fruit on display

in the train-car womb

O clear beast, you

fill glass

with light

and smolder!

I find the interjection of light here to be especially interesting. Throughout Bilotserkivets’ work, light seems to be more of a threatening glow, a promise for destruction, yet I cannot help but want to complicate this image with the tenuous threads of hope that light often signifies. In thinking of hope, I must bring in a final poem of Bilotserkivets, one that I think summarizes that journey from individual to localized survival perfectly, in “February,”

It’s the last month of a long winter

we’ll survive. After all, we were at fault

for something. From the darkness,

a knife emerges like the moon. A guitar

strums about corpses and forests

while our voices endure on cassettes.

Some owe less—others more.

Some more—others, less. Out of our hands

years crawl like worms. Yet,

there’s punishment for everything.

That first sentence, “It’s the last month of a long winter/ we’ll survive.” With no complicating punctuation other than the line break, it reads like despite the implicit and mountainous threats of immense destruction–explosions, reactors warming, the heat’s ticking countdown to doom –heat fades, energy dissipates, and one (all) will survive as endurance is a gift granted upon bloom. This poem certainly is not a Gloria Gaynor anthem vis-à-vis “We Will Survive,” though, as what follows this first line is complicated with themes of punishment, and emergent violence. We echo back to that core distinction between individual instinct and community survival, how after the individual is communalized for survival, so too is consequence. Bilotserkivets’ work continues to expand the domain of survival into that quantum territory–every little boundary, every atom of individuality contributes to a unique sense of survival that intercepts with the more communal and collective forms relied upon for hope and drive.

These dimensions of survival – the individual and local – will inevitably get expanded during the processing stage in which a collective must ask: what has happened to us, what are we? This post-processing–what does it mean to exist in a country, in a world, that has been attacked like this, that has been damaged in these ways, in a global perspective, in the sense of someone visiting towns they once knew as whole and now must reconcile as broken – expands the boundaries of individual fears, jobs, and spirit. The aforementioned poem, ‘conversations about war but not only,’ continues with

i say, no-no, what we have is a war

that is I use some other, methodologically more correct term,

but what i really mean is war,

the one with many names

the most frightening of them being the polite ones

for example, a conflict

a conflict in the east

where something was left unresolved,

These lines capture something I find central to my reading of these collections as approaching survival’s quantum nature, to turbulence, vortices, Deleuze and Guattari: the disruption of politeness. Further highlighted in “genius loci,”

such a country, you see, such a country. and what were you thinking, really? what did you expect?—the law stands guarding our peace of mind. neighborhoods are patrolled by volunteers. garbage is sorted. bird feeders are put up. rabbits leap over railroad tracks and fall off the margins of history textbooks. bombs go off in stadiums. computers play go. stars blaze and vanish, like snapchat messages. androids dream of electric sheep. the law that stands guarding our peace of mind has large fists.

It is an especially evocative listing to put neighborhood patrols, rabbits leaping over railroad tracks, and bombs going off within the same sentiment of understanding. Whereas Bilotserkivets speaks of the immediacy of survival,–what do I and You have to do in order to get beyond this current or recently passed stage of destruction and horror–Shuvalova picks up with the implicit question of how are you acting to remember that this is not something that just passes for everybody, that in order to read about these horrors they must be experienced by real, living countries.

If the miracle Bilotserkivets accomplishes is to survive at all, the miracle Shuvalova accomplishes is to bring forth the categorical superstructures that restrain and threaten us even after such nationally dismantling violence such as war. There is a certain erotics in poems like, ‘a deer,’ which asks,

who gave you

this great unconquerable sadness

with an uncertain and viscous taste

like ripe elderberries

rusty like iron

at the bottom of a well

This beautiful image speaks of knowing someone and tasting not only the tangible flavors but also those metaphysical ones, the furrowed emotions of intimacy. The poem continues to wind through with stanzas that ask ‘who is calling you,’ ‘who holds you,’ ‘who is standing there,’ narrating the tension of the poem. I interpret the ‘you’ of this poem to be they who need to be taught how to survive–as the poem ends with the subject for each of these questions, the ‘who,’ is compared to a deer alerting you and running deeper into the forest. Additionally, this poem brings in the complicated titular image of empty wells, wherein Shuvalova depicts both real scenarios–the societal threat of corrupted water supplies or limited water access and the metaphysical conflict of individuals becoming these empty wells, structures capable of drawing forth work but resulting in no reward.

Shuvalova seems most interested in, as documented in “conversations about war but not only,” what one recalls, what anyone recalls, of the historical elements of an event that results in survival. In this era where small bombs make large explosions and create death lists of hundreds, thousands, tens of thousands of individuals in instants, the anonymity of a nation-state stating, “492 citizens were killed this week,” allows it to maintain a certain distance from the watchers and interpreters of history. The action of drawing from wells is equated to the action of producing names as illustrated in her poem, “into the sweet orchard,”

each time you enter you won’t have a name

each time you enter you’ll carry a mouthful of names

you’ll swallow them beyond the gates

so that again you won’t have any

so that you can return

Often the most radical thing someone can do in recalling the history of contemporary violence is to list out all of the names of the dead in these events. I think of the wonderful author Jamil Jan Kochai, who during a workshop submitted a poem that was a list of the names of Afghan girls, boys, and teenagers who’d been slaughtered in the U.S. war in Afghanistan, and how after reading this poem the class was then asked to critique it or offer suggestions or debate the poiesis of the poem, as one does in poetry workshops, and how the class could not offer any meaningful or constructive criticism on the poem because what more can you say other than a name?

From any direction and toward any scope of temporality, survival is a structure that pressures those within it. Shuvalova’s “Ladder” demonstrates this pressure with a combinatory image from Bilotserkivets’ work and the culminating and existential horror documented within her own,

the weight of long days

covers us like a heavy blanket,

car lights tram lights scatter through the window.

the frightened arrow of the barometer

trembles inside,

announcing

darkness.

After all, this is what entering the domain of survival is: an announcement of darkness.

—-

Cody Stetzel is a San Francisco resident working within electrical engineering. They have worked as the managing editor for Five:2:One Magazine, and a poetry editor for the Rise Up Review. They were a staff book reviewer for Glass Poetry Press and also a volunteer organizer and event staff for Seattle’s poetry bookstore Open Books: A Poem Emporium. They are currently a contributing writer for both Poetry Northwest and the Colorado Review where they offer reviews and criticism of contemporary poetry. Their writing can be found previously in Poetry Northwest, The Colorado Review, Birmingham Arts Journal, Across the Margins, Boston Accent Literature, Aster(ix) Journal, and Glass Poetry Press. They received their Masters in Creative Writing for Poetry from the University of California at Davis. Find them on Twitter @pretzelco or at their website www.codystetzel.com.

Natalka Bilotserkivets’ work, known for lyricism and the quiet power of despair, became hallmarks of Ukraine’s literary life of the 1980s and 1990s. The collections Allergy (1999) and Central Hotel (2004) were the winners of Book of the Month contests in 2000 and 2004 respectively. In the West, she’s mostly known on the strength of a handful of widely translated poems, while the better part of her oeuvre remains unknown. She lives and works in Kyiv. Her poem, “We’ll Not Die in Paris,” became the hymn of the post-Chornobyl generation of young Ukrainians that helped topple the Soviet Union.

Ali Kinsella has been translating from Ukrainian for eight years. Her published works include essays, poetry, monographs, and subtitles to various films. She holds an MA from Columbia University, where she wrote a thesis on the intersection of feminism and nationalism in small states. A former Peace Corps volunteer, Ali lived in Ukraine for nearly five years. She is currently in Chicago, where she also sometimes works as a baker.

Pushcart prize poet, translator, and a founding editor of Four Way Books, Dzvinia Orlowsky is author of six poetry collections published by Carnegie Mellon University Press, including Bad Harvest, a 2019 Massachusetts Book Awards “Must Read” in Poetry. Her translation from the Ukrainian of Alexander Dovzhenko’s novella, The Enchanted Desna, was published by House Between Water Press in 2006, and in 2014, Dialogos published Jeff Friedman’s and her co-translation of Memorials: A Selection by Polish poet Mieczslaw Jastrun for which she and Friedman were awarded a 2016 National Endowment for the Arts Literature Translation Fellowship.

Iryna Shuvalova is a poet, translator and scholar from Kyiv, Ukraine. She has authored three poetry collections in Ukrainian—Ran, Os and Az—winning some of the country’s top awards for poetry, including, in 2010, the first 1st place in the Smoloskyp Poetry Prize awarded in ten years. Her fourth book of poems is forthcoming in 2020 with The Old Lion Publishing House in Lviv. Iryna’s translations from Ukrainian and Russian appeared in Modern Poetry in Translation and Words without Borders among others, while her own poetry has been widely anthologized in Ukraine and translated into nine languages beyond. In 2009, she also co-edited the first anthology of queer writing in Ukrainian translation, 120 Pages of ‘Sodom.’ In 2012, she was awarded the Joseph Brodsky / Stephen Spender Prize for poetry translation. Having previously earned her MA in Comparative Literature from Dartmouth College on a Fulbright scholarship, she is now a PhD student and a Gates Cambridge scholar at the University of Cambridge where she studies communities affected by the War in Donbas, Ukraine through the prism of war songs.

Olena Jennings is the author of the poetry collections The Age of Secrets (Lost Horse Press) and Songs from an Apartment. Her novel Temporary Shelter was released in 2021 from Cervena Barva Press. Her translation of Vasyl Makhno’s poetry collection Paper Bridge was released from Plamen Press. She holds an MFA from Columbia University and an MA from the University of Alberta. She is the founder and curator of the Poets of Queens reading series and press. (photo by Roman Turovsky)