by Luther Hughes | Contributing Writer

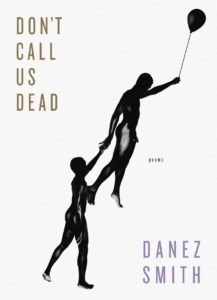

Cover image: “Dreams In Black and White”, 2013, courtesy of the artist, Shikeith

This essay is part of a series in which Poetry Northwest partners with Seattle Arts & Lectures to present reflections on visiting writers from the SAL Poetry Series. Danez Smith reads at 7:30 p.m. on Monday, November 26 at Broadway Performance Hall—Seattle Central College.

Don’t Call Us Dead

Don’t Call Us Dead

Danez Smith

Graywolf Press, 2017

1.

I used to own a plant, or better put, my old roommate and I used to own a plant. We decided the plant was nonbinary and named them “Stardust.” Stardust was a succulent. They barely needed water or to be touched, catered to. The only thing they really needed was sunlight, but Stardust began dying after only a few weeks. I Googled, “how to keep your succulent from dying,” but there weren’t many answers. Our friends told us how easy it was for succulents to die, but we had our hopes. After a few months passed, Stardust was half dead, a mere ghost of who they were, and I began to clip the dying appendages. My roommate left soon after; we were both moving out—back to our respective home cities. The day I moved out of our apartment, I left Stardust in my roommate’s room, so they could die in the sun. I don’t know why, but I wanted their death, if it were to come before my landlord threw them out, to be peaceful. Or maybe, just maybe, my landlord would see Stardust and adopt them for himself, Stardust leaning into the sun saying, “I’m not dead, not yet.”

2.

While rereading Danez Smith’s second collection, Don’t Call Us Dead, I am reminded of Stardust. Through lamentation and joy, Smith’s poems lean their head back and sing, “Not yet.” And this singing—how it unravels something in me, call it an awakening—speaks to how I move throughout the world, how the world moves through me.

I’m on the bus going to work when I see two police officers surrounding a black man downtown. Or I’m walking home and, in the Fred Meyer parking lot, a police car swerves into the parking space next to a downed brown woman, another police officer’s knee pinned against her spine. I open my bookbag and begin reading the first few couplets of Don’t Call Us Dead, from the poem, “summer, somewhere”:

somewhere, a sun. below, boys brown

as rye play the dozens & ball, jumpin the air & stay there. boys become new

moons, gum-dark on all sides, beg bruise-blue water to fly, at least tide, at least

spit back a father or two. i won’t get started.history is what it is. it knows what it did.

bad dog. bad blood. bad day to be a boy

“[H]istory is what it is. it knows what it did” guts me. In these first few couplets, there is an attempt to want to talk about the deaths of black and brown boys, but the speaker retreats multiple times: “i won’t get started” is the first step away; “history is what it is. it knows what it did” is the second. Immediately there is pain. There is so much pain that instead of talking about death, the speaker wants to talk about life, or more so, imagining the lives of black and brown boys: “somewhere, a sun. below, boys brown.” Smith is saying, “I will focus on joy,” similar to Ross Gay ending his poem, “Sorrow Is Not My Name,” with “My color’s green. I’m spring,” similar to Stardust saying, “Not yet.”

3.

Last year, my roommate threw a party for his birthday. Danez was in town or was passing through, and I invited them to come over. On TV, we played a black movie. I don’t remember which one it was, but it resembled a lot of old-school 90s black movies, those in which someone dies at the end, or in the beginning (to conjure the narrative), or somewhere in the middle (just when you’re thinking, “Maybe not this time.”). Whichever movie it was, there was a death. We all watched the scene, stopped ourselves from drinking, laughing, dancing to the music—“Knuck If You Buck” was on at the time. It was the epitome of blackness, if I could say so. But that death, whoever it was, whoever played the part too well, hit all of us just for a split second.

On Twitter, Danez tweeted about that night, saying they had fun and, from now on at their parties, they would play movies with black joy instead of movies with us dying. I retweeted it.

Now, I’m thinking of Danez’s poem, “dinosaurs in the hood,” of the chant-like line, “& no one kills the black boy. & no one kills the black boy. & no one kills the black boy.”

4.

In the poem, “seroconversion,” I am reminded of how one reimagines a world, and how the speaker finds themselves dying. The poem retells what could be the same story in five different parts.

Here is the world building in the first section of the poem:

boy reaches his bare hand inside the other, pulls

out a parade of fantastic beasts: lions with house

fly wings, fish who thrive in boiling water, horses

who’ve learned to sleep while running. he pulls

out beasts, one by one, until all the magic is gone

& the gutted boy turns into a pig. pig boy & boy

spend a day with no language & the boy, hearing

no protest, splits the pig open & crawls right in,

& the pig, not one to protest, divides in half & lets

the boy think he split him. when they’re finished,

they dress & part & never forget what happened.

how can they? the boy’s still covered in pig

blood, the pig’s still split.

What strikes me most about this section, besides the world building, is what’s in the world: “lions with house fly wings,” “fish who thrive in boiling water,” and “horses who’ve learned to sleep while running.” Everything in this world has been created to survive and has been pulled out by the boy until the boy himself is without survival. In some ways, it’s beautiful: the world building, the animals. But at the same time it’s very sad. As the section continues, the no-magic boy becomes a pig and the pig is split open like meal preparation, but is instead used as shelter: “splits the pig open & crawls right in.” The section ends with the physical separation of the two boys, but the splitting, or the act of having been split, stays. The poem is about contracting HIV, and what was magical inside the boy—what made him survive—has been gutted and now he cannot survive because he has contracted a chronic disease.

Each section of this poem does the labor of trying to accurately retell this contraction, using different metaphors—gods, bread, medieval caricatures, and nature. I don’t think the poem settles on the last section being the most accurate telling, but the poem ends with the lines, “& he swore he heard the / dirt singing his name // saying it right,” as if saying the poem is more concerned with how the boy accepts this contraction—his possible death—more so than the contraction itself. In this way, the boy is at peace.

5.

Smith’s work is beautifully vulnerable. I don’t say this because of what they address or interrogate, although that should be noted. I say this because of their commitment to obsession. Throughout their work—in this book particularly—they dig into themes such as perseverance, death, boyhood, livelihood, bondage, intimacy, innocence, and blood. This tells me that these obsessions keep them up at night, knock on their window, sleep under their bed. They are restless. And this is what I love about reading Smith’s work. It’s not only about interrogating the blood or the body, but about living with what haunts you.

In the poem, “litany with blood all over,” we see how the speaker is haunted. The first lines of the poem are, after all:

i am telling you something i got blood on the brain

As the poem unravels, so does the speaker. And in tandem, so do we, as readers. The speaker treats “blood” as more than just the fluid inside our bodies, but as a living thing.

It raises children:

i let the blood

raise my boy

It buries:

i let the blood

bury him too

It screams and has songs:

blood & its endless screaming

or singing

or whatever people do when their village burnsagain the blood & its clever songs

The speaker has so many faces for blood that blood almost seems to replace them as a human. All that is left is the blood, or the blood of two people. In fact, the speaker gets erased, becomes a “wife” of sorts: “i touched the boy & now i have his name.” This poem is more than haunting. It’s almost violent in its delivery of how blood operates and erases or marries the two. The poem ends with this marriage, overlapping and flooding the page with the phrases: “his blood” and “my blood.” The overlapping becomes so excessive that it becomes difficult for the phrases to be read. Eventually there is only the muddying of each other’s blood.

6.

When asked to write this essay/review, I knew I somehow wanted to talk about the poem, “not an elegy,” in relation to joy, resistance, and survival. Here is the poem’s first section:

how long

does it take

a story

to become

a legend?

how long before

a legend

becomes

a god or

forgotten?

ask the rain

what it was

like to be the river

then ask the river

who it drowned.

I knew I wanted to talk about this poem because of how I’ve been feeling as of late. I have been depressed. I have wanted joy in the darkest hours. I have cried myself to sleep thinking about the death of black and brown bodies. I am a swamp. I am stuck. This poem reminds me of this, yes, but to also keep pushing. It reminds me that I am not alone. It tells me that blackness, black people, black bodies will outlive all of this and then some. And in some ways, this poem, each section, is a different call-to-action, a different way to spell joy. Hence the title of the poem itself.

I am particularly drawn to the lines of a later section:

i have no more

room for grief.it’s everywhere now.

listen to my laugh& if you pay attention

you’ll hear a wake.

Perhaps what I love most about this poem—and quite frankly most of the poems that take this form—is the couplets. There is a duality the poem takes that speaks both to death and to joy, whereas, say, tercets couldn’t have the same effect. In the lines above, there’s a wake in the midst of laughter. Couplets highlight the back and forth between the two binaries (if I could call them that). There is restlessness between them, a restlessness that tries to occasionally break away when there is a monostich: “i demand a war to bring the dead child back. // i at least demand a song.” But the restlessness always returns. Until, one could argue, the last few lines of the poem:

he saw something. i think that’s it. he saw something

what? the world? a road?

trees? a pair of ivory hands?

his reflection?

his son’s?

a river saying his name?

The interrogation of reason at the end of the poem resonates with me. I read this last section as being about suicide. Earlier in the section, Smith includes the line: “i forgot black boys leave that way too.” Recently, I have told people about my depression and my thoughts on committing suicide. From family, I got asked:

Why would you want to kill yourself?

Don’t you know people love you?

Is it because of me?

Don’t you know God loves you?

Is it work?

Are you lonely?

Are you seeing a therapist?

Is this because of what happened when you were younger?

The truth is, I don’t know why. I told them this, but the questions continued. It didn’t bother me. Everyone wants to reason for death, for dying. Nobody truly knows where we go once we leave this earth. But, as for me, I thank Smith for Don’t Call Us Dead. I thank Stardust for allowing me to take care of them as much as I could.

Dear Stardust, Dear Danez,

Today, I will watch a black movie with a glass of wine and laugh. And the black boy in this movie will not die. And I will not die. I will tilt my head back and sing, Not yet.

Luther Hughes is a Seattle native and author of Touched (Sibling Rivalry Press, 2018). He is the Founding Editor of The Shade Journal and Executive Editor for the The Offing. His work has been published or is forthcoming in Poetry, New England Review, TriQuarterly, Washington Square Review, and others. Luther received his MFA from Washington University in St. Louis. You can follow him on Twitter @lutherxhughes. He thinks you are beautiful.