by Han VanderHart | Contributing Writer

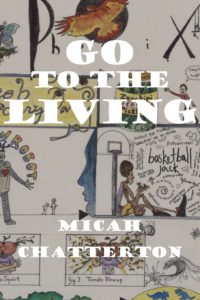

Go to the Living

Micah Chatterton

Inlandia Books, 2017

In the autumn of 1883, following the death of her eight-year-old nephew Gilbert, Emily Dickinson begins a letter to her friend Elizabeth Holland with the lines:

Sweet sister.

Was that what I used to call you?

I hardly recollect, all seems so different-

I hesitate which word to take, as I can take but few and each must be the chiefest, but recall that Earth’s most graphic transaction is placed within a syllable, nay, even a gaze-

I turn instinctively to Dickinson’s grief in reading Micah Chatterton’s Go to the Living, a collection of memoir-driven lyrics that chronicles the story of Micah’s son Ezra Chatterton, who died of cancer. Dickinson’s letter shows us not only of the difficulty of searching for names and words in the face of grief (“Was that what I used to call you?”) but reminds us that our tragedies are written in syllable and gaze—the smallest units of sound and sight we have of each other.

Units of sound and sight, time and space(s), and physical and spiritual geographies are a few of the ways Chatterton’s poetry makes poems out of a parental experience of grief, suffering, and love. Chatterton’s poetry works with found texts: text messages transcribed from his son Ezra’s phone, collaged condolences, lists, and Ezra’s many nicknames (“all those middle names you kept giving yourself”).

Interspersed throughout Go to the Living are haibun—a prose and tanka hybrid form, named for Basho’s “poetic-prose travel journals.” Interspersed in Chatterton’s haibun are Ezra’s ashes, scattered and placed by the poems’ speaker in a number of significant locations. The flexibility of the form, with its wider, journalistic prose-poem beginning, and compact, tanka-length lyric at the end, makes it an ideal vessel for Chatterton’s lyric-narratives. The title of each haibun, inverted and placed at the bottom of the poem, names the place, and sometimes the time, of the poem. The haibun’s progressive narrowing to tanka and then title in Chatterton’s formation, visually enacts Dickinson’s urging to “recall that Earth’s most graphic transaction is placed within a syllable, nay, even a gaze—.” Take Chatterton’s first haibun in Go to the Living, “—Toward Tulum, November.” It opens:

I first tipped the bottle north, a brittle tube with your name wrapped around its neck, toward the empty temple just up the coast, toward the salt-bleached block ruins quarried from the interior, now nests for grey iguanas. Inch-high waves broke on my ribs. When I tipped the bottle into my hand I imagined the ashes would plume behind me like smoke from a thurible, but they just disappeared as my fist submerged, as they always will in water. On shore, a Yucatan cat, bright black, snatched a crab from the sand and carried it, legs whirring, into the tall grass, her dew-slicked belly mooning under her.

“—Toward Tulum, November” is the first haibun and second poem in the book. It comes after a five-section poem “First, Language,” in which a child learns words in Spanish (“La lengua, tongue. / La sal, salt.”) and fishes rocks from a creek while camping with his father. The reader has just come from a poem where a living child, “snags a bit of pitted limestone from the sand,” and turns to the father to ask, “This one? he presses, cradling the question to my face.” This intimate image, the child’s hand pushed into the parent’s face and gaze, is still with the reader as they turn the page to the poem “—Toward Tulum, November,” and enter into the knowledge that the “brittle tube with your name wrapped around its neck” is a vial of the child’s ashes. There, the father imagines himself in a priest-like role, swinging a thurible, incense and smoke wafting. From this sacred image, the poem’s attention centers on the physical property of the ashes, sinking in water. A cat hunts a crab. “All my dreams end in a death,” the narrator confesses—and yet we are in a pilgrimage of lyric movement, and song, and what grows out of song. The reader is also entering into a beginning, even here, in Tulum, in November: “I had to pick a place to begin, and that was the farthest from our home I’d ever been.” The speaker names a hesitation here to choose a geographic-poetic place to begin, much as Dickinson confesses to not knowing which word to “take” when writing a letter to her friend from a place of unmarked. The speaker also turns to syllable and gaze here, closing with the tanka:

Clouds and their shadows

make land here. Families of fish

leap, shudder like coins,

wishes. Are these enough to call

a place and moment sacred?

In this tanka resides a tension between form and creative desire: the idea that the poet and speaker must choose “a place to begin” and images “enough to call / a place and moment sacred” while working within the guidance of limited syllables and the knowledge that the tanka form “must end within those bounds” (see Chatterton’s “A Note on Forms” at the end of the collection). Poetic craft is here comfort and solace—the possibility of form emerging from the formlessness, and limit from the limitlessness, of grief’s pain. Chatterton’s poems act as urns and vials for Ezra’s ashes—but even more than this, these poems are commemorations of Ezra’s living body. We speak, after all, about texts in the present tense, because texts are living, and do not die.

I’m not someone generally moved to tears by tragedy in art, but I wept, alone in my house, over this book. In Book I of the Confessions, Saint Augustine famously writes about experiencing grief through art and how he wept for the death of Dido and her love for Aeneas, but not for the state of his own soul. In Book III of the Confessions, Augustine revisits this theme by considering tragic theater and asks, “Why is it that a person should wish to experience suffering by watching grievous and tragic events which he himself would not wish to endure?” Augustine’s criticism of watching tragic performances rests in the deeply uncomfortable judgment that there is pleasure in witnessing tragedy, and experiencing pain, as an audience member. But although there’s a generic difference between Augustine’s example of tragedy and Micah Chatterton’s Go to the Living—one is fiction, which Augustine directly addresses, and one is memoir—Augustine has a line that speaks to my experience of reading alone in my house, crying over a book of poetry: “A member of the audience is not excited to offer help, but invited only to grieve.”

Why carry Saint Augustine to the life stories of Ezra and Micah Chatterton, figured epically in the poem “What I said” as “two heroes who love each other completely?” Because, as Augustine realizes in writing and examining his grief, “Tears and agonies … are objects of love.” Go to the Living is an invitation to these objects of love: Ezra’s text messages, the Fathers’ Day letter he writes Micah (“Dear Dad, Father, Sensei, Royal Kicker of Asses”), as well as Micah’s lists—a list journal of Ezra’s headaches and nausea, a list of things to do before suicide (“Things to do Before I Can Kill Myself”), a list of grieving questions (“Questions”), a list of instructions for self-hypnosis (“Self-Hypnosis”). The other object of love in the poems are Ezra’s ashes, carried, relic-like, by the poet-father and speaker.

Go to the Living is a remarkable debut collection, brimming with orphic forms that call us both to and back from our griefs. It is an invitation to “earth’s most graphic transaction”—the love, life and death of a beloved. It is a handshake over an abyss.

Han VanderHart lives in Durham, NC. She has her MFA from George Mason University, and is currently at Duke University writing her dissertation on collaborative poetry in the Renaissance. She has poetry and reviews published and forthcoming in The Kenyon Review, The Greensboro Review, The McNeese Review, Thrush Poetry Journal, American Poetry Review, The Indianapolis Review and storySouth. Her chapbook, What Pecan Light, is forthcoming from Bull City Press, and she is the Reviews Editor at EcoTheo Review. More at: hannahvanderhart.com