by James Crews | Contributing Writer

Kindest Regards: New and Selected Poems

Ted Kooser

Copper Canyon Press, 2018

Reading Ted Kooser’s work, I often think of what Old Testament scholar Walter Brueggeman wrote in his book, Sabbath as Resistance: “Worship that does not lead to neighborly compassion cannot be faithful worship.” This sense of neighborliness has been apparent in the poetry of Kooser, who served two terms as U.S. Poet Laureate, ever since he began publishing over fifty years ago. He is the author of more than a dozen collections of poetry and several works of prose, including three children’s picture books. His communion with the world, even with the strangers he encounters, however, has never been more obvious than in his latest collection, Kindest Regards: New and Selected Poems, which gathers samples from his previous books and offers a swath of transcendent new poems, which prove that the best from this poet is perhaps yet to come.

Among these new selections, numerous poems of observation enshrine the kind of close attention to detail that has made Kooser one of our finest writers. Like the Nobel Prize-winning Irish poet, Seamus Heaney, Kooser’s work also seeks to “exalt everyday miracles and the living past” (as Heaney’s Nobel Citation pointed out), but Kooser does so using language so deceptively simple that a person from any background might understand and appreciate his poems, no matter their training or education. For all the plainness, though, Kooser’s poems ultimately model a new way of absorbing the seemingly ordinary world, especially in his use of extended metaphor. In “A Washing of Hands,” for instance, from his Pulitzer Prize-winning Delights & Shadows (2004), the simple act of turning on the faucet takes on an almost magical quality:

She turned on the tap and a silver braid

unraveled over her fingers.

She cupped them, weighing that tassel,

first in one hand and then the other,

then pinched through the threads

as if searching for something . . .

These poems train us to pay attention to what we might be tempted to ignore in pursuit of the louder and more colorful entertainments now available to us at the touch of a screen. Yet even the briefest moments that Kooser preserves can lead us more deeply into our own lives. In fact, the short poem, “Hoarfrost,” which describes a simple walk through “icy prairie fog,” flawlessly conveys the overarching intention of his work. Most of us have heard ice compared to lace before, but few poets have followed the image with such dexterity and clarity, as Kooser does here:

it is like finding your way

through a wedding dress, the sky

inside it cold and satiny . . .

Indeed, his connection to the scene before him brings this speaker fully into the present moment, and as usual, he takes us with him:

no past, no future, just the now

all breathless. Then a red bird

like a pinprick changes everything.

Because he had already been paying such close attention, he was also present for that next, dramatic shift in perception—the lone “pinprick” of color that like awareness itself weaves through what might have been an otherwise unremarkable winter scene. Kooser’s poems often evoke for me Henry David Thoreau’s now-famous line: “Only that day dawns to which we are awake.”

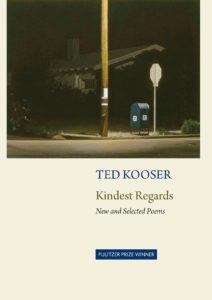

Critics of Kooser are fond of pointing out his conversational style and accessible subject matter, yet few speculate as to why such a distinguished poet might consciously and continuously choose this way of addressing readers. Given the title of this new book, Kindest Regards, and the painting of a mailbox on a street corner on the cover, it is difficult not to see Kooser’s poems as a kind of intimate correspondence with his audience. Correspondence can be, of course, a literal exchange of letters, or a description of how things seem similar and fit together. But the roots of the word (cor, meaning “together;” re-, meaning “in return”; and spondere, meaning “to promise”) also combine to form the phrase, “returning the promise together.” The promise that these poems make, as long as we are willing to participate in the exchange, is a relatable, clear communication that allows us to see the everyday world in striking new ways. Kooser speaks to us as if we were neighbors gathered in the grocery store parking lot or around a barbecue pit in someone’s backyard—as if we’ve known each other for years.

Indeed, one of his most anthologized poems, “Splitting an Order,” which also served as the title of his excellent previous collection, begins as if we were already in the middle of a conversation with him: “I like to watch an old man cutting a sandwich in half . . . ,” he writes. Yet the scene he describes—of an elderly couple splitting “an ordinary cold roast beef on whole wheat bread”—brings both the poet and that couple closer to us as well. Another of his newer poems, “Passing Through”, recounts his sighting of a man standing outside on a break from work:

He was beside me for only an instant,

wearing a short-sleeve yellow shirt

and gray work pants, as the hand

that held the cigarette swept out

and away, and he turned to watch it

as with the tip of a finger he tapped

once at the ash, which began to drift

into that moment already behind us,

as I, with the others, sped on.

Kooser suggests there is something essential about this man as well as his own recollection of the brief encounter in painstaking detail, right down to the tip of the man’s finger as “he tapped once at the ash.” Perhaps Kooser means to help us see, at a time when we are growing increasingly isolated from each other, that we do leave a mark on every person we meet, whether we intend to or not. He illustrates this point repeatedly in several of these new poems, in which he shows us a man singing “in a doctor’s crowded waiting room”; a man standing alone on a bridge, “hands clamped to the cold iron rail”; “a tiny ballerina of a man” perched on the back of a garbage truck; and “a woman and a small child . . . sitting in wind on the slope, / looking down at the traffic.” Even a name written in faded ink on the back of an old snapshot becomes an occasion for the poet to imagine himself into the life of that photographed young man, “pinching the brim of his hat, / smiling into the lens.” Kooser thus shows us how to live with a closer affinity to the people we find in our vicinity, even those who do not seem at first so consequential. In order for us to be able to feel empathy, after all, we must first develop the ability to step into another’s shoes, even if just for an instant.

Some might question the necessity of holding onto such passing moments, especially at a time when the world seems more and more in crisis. Why write about that man smoking outside the warehouse, or that mother and child bundled up on the slope, looking out together at the cars below? Kooser’s answer, of course, rests in the inherent intimacy of poem after poem, which turn ordinary acts and words into sacraments for the reader, using nothing more than the authentic power of his own honed attention. “At Nightfall,” from his collection, One World at a Time (1985), argues most potently why each of us needs to hold onto those brief streaks of connection for as long as we can. The poem begins:

In feathers the color of dusk, a swallow,

up under the shadowy eaves of the barn,

weaves now, with skillful beak and chitter,

one bright white feather into her nest

to guide her flight home in the darkness.

Kooser suggests in these timely lines that we too need the “bright white feathers” of hope to keep us focused and “guide” us back home into deeper connection with each other and our world. Our culture often urges us to look past such everyday miracles as a swallow wisely weaving that single feather into her nest, yet Kooser ends this subversively simple poem with a sincere and unwavering question meant to jolt us awake:

. . . But to what

safe place shall any of us return

in the last smoky nightfall,

when we in our madness have put the torch

to the hope in every nest and feather?

If we are to regard each other in the kindest ways possible (as the title of this volume suggests), Kooser’s poems imply that we must first acknowledge one another’s existence like the neighbors we already are. A shift in perception is always possible (I think again of that “red bird / like a pinprick”), but it starts in our hearts and minds, when we see that giving our attention to what’s at hand is an act of generosity and devotion both. As Kooser has been gently attempting to show us for more than half a century now, that kind of attention is not only useful; it changes the world.

—

James Crews is the author of two full-length collections of poetry, The Book of What Stays and Telling My Father. He is also the editor of Healing the Divide: Poems of Kindness and Connection, published by Green Writers Press, and lives on part of an organic farm with his husband in Shaftsbury, Vermont. He leads Mindfulness and Writing workshops throughout the country.