by Saddiq Dzukogi | Contributing Writer

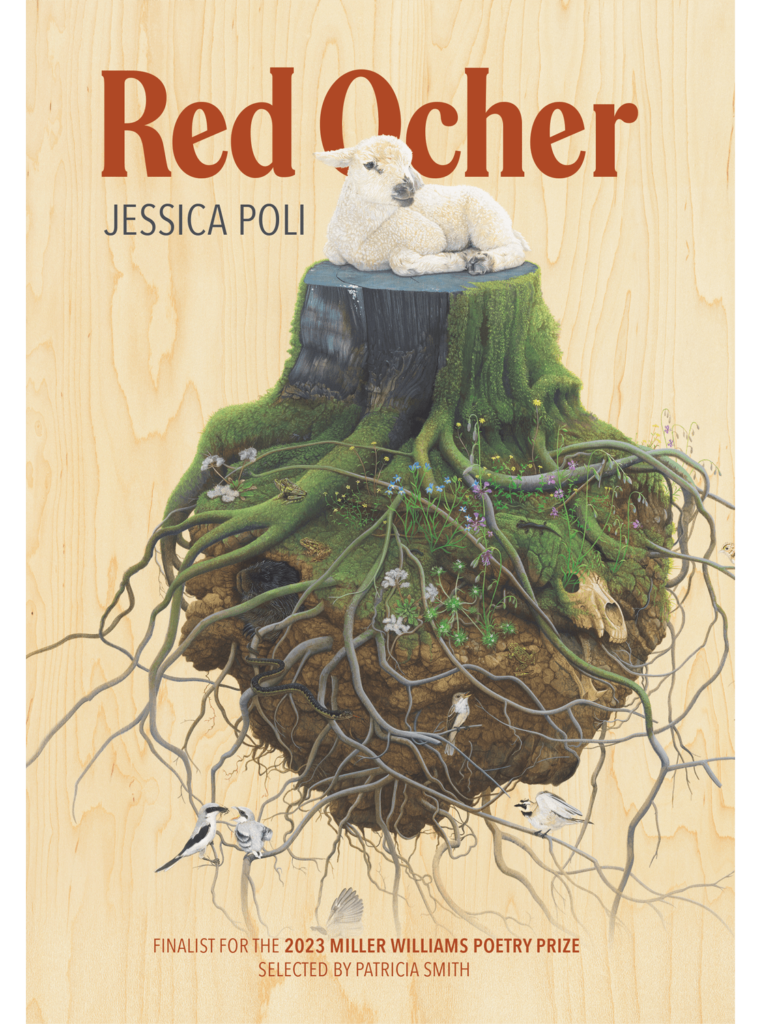

In the realm of literary enchantment, Jessica Poli’s debut poetry collection Red Ocher (The University of Arkansas Press, 2023), which was a finalist of the Miller Williams Poetry Prize, stands as a mesmerizing testament to the beauty and intricacies of existence. Delving deep into the jurisdictions of human experience, Poli skillfully crafts a poetic tapestry, where words intertwine and harmonize to create a mesmerizing mosaic of language and meaning. However, beyond poetry, Poli is also deeply connected to the earth, nurturing life through her passion for farming. In this interview, she sat down with Saddiq Dzukogi to explore the convergence of these two profound passions in her life. Through this conversation, Poli illuminates the parallels between the world of agriculture and the world of poetry, showcasing how both require unwavering attention and profound devotion. As Poli’s words unfold, a vivid portrait emerges, unveiling the transformative power of attentiveness and the ways in which tending to the earth nurtures her poetic sensibilities.

Saddiq Dzukogi (SD): Congratulations on the release of your debut poetry collection, Red Ocher. It is such a stunning book, and I absolutely enjoyed my time with it. As someone who enjoys getting their hands dirty in the soil, cultivating and nurturing life, I remember you once shared your love for this process. It made me wonder; how do you compare farming to poetry? Are there points of convergence for these two obsessions? How does farming and tending to things nourish your poetic sensibilities?

Jessica Poli (JP): I love this question! Thank you so much for this. I fell into farming when I started a summer job on a small family farm while I was completing my MFA program. So right from the start, there was a relationship there; I’d spend about half the year reading, writing, and teaching, and half the year working with my hands in the dirt. It instantly felt like the right balance for me, especially because both forms of work (academic and agricultural) give me space, in their own ways, for thinking about poetry. When I’m out in the field, weeding or planting or harvesting, sometimes I’m thinking about poems or working on one in my head. But more often I’m simply practicing my capacity to pay attention, which is where poetry, at its root, begins. Because so much of the labor of agriculture is repetitive, I tend to fall into a rhythm, muscle memory guiding the work, which lets my attention move to what’s going on around me: the sound of a hawk screeching in the tree line at the edge of the asparagus field, or the smell of marigolds suddenly filling the air because a coworker walked through the flower patch upwind of me just moments before. Sometimes these things become poems and sometimes they don’t. What nourishes me the most, I think, is the practice of attention itself.

(When I was thinking about this question, I looked up the word attention in the thesaurus, and one entry that popped up was devotion. That feels right.)

I also think it’s important that both involve making things: a poem, or a head of lettuce or row of cabbage. One day the ground looks empty, and before you know it, the thing you’ve been nurturing emerges. Carrots are always slow to germinate—slow enough that there’s usually a moment of anxiety, a “Did-it-work?” lingering in the air. When they finally sprout, it feels a little miraculous, the same way some poems feel when they first appear.

SD: Stunning insight. I like the practice of attention too—I have often found curiosity to be the way to discovering amazing poetry—both as a reader and as a poet. What books or poets, if any, were instrumental to your writing Red Ocher? Or what music or anchor kept you tethered to the intimate processes of creating and refining?

JP: I love the idea of art being an anchor for creating something else. Aimee Man’s album Mental Illness immediately comes to mind; I had it on repeat for a solid year in the middle of writing many of the poems that would end up becoming Red Ocher. When I listen to it now, I can still picture the gorge road I’d be driving on my way to work in the morning as “Patient Zero” starts to play (I had it on a CD in my car, so certain tracks always came on at the same time during my daily commute). I also think about this bright red portable cassette player that I always carried in my bag for a while, pulling it out on lake beaches or around campfires to play Patti Smith’s Horses, or Hank Williams, or Bessie Smith.

In poetry, Sara Eliza Johnson’s Bone Map is one collection that I’ve kept returning to for years, and it felt especially influential to me throughout writing this book. A single poem I kept coming back to is Lynn Emanuel’s “Frying Trout While Drunk,” from her collection Hotel Fiesta. There were other books that I came across right when I needed them most, it seemed: Ai’s Cruelty, Ellen Bass’ Mules of Love, Dorianne Laux’s What We Carry, and Leila Chatti’s Deluge. Others who I was reading a lot of at the time of writing these poems (an incomplete list and in no particular order): Natalie Diaz, Alejandra Pizarnik, Ada Limón, Arthur Sze, Camille Dungy, W.S. Merwin, Traci Brimhall, Jennifer Elise Foerster, Donika Kelly, Catherine Barnett, Aimee Nezhukumatathil, Joy Harjo, Michael Burkard, Jane Wong, Diane Seuss, Gregory Orr, Mary Ruefle, and Ross Gay.

SD: In “Ghazal for an Imagined Future,” the poem begins with a description of a lost memory—a road leading to a house in an open field—which is now nothing more than a silent husk. One of the most striking aspects of the poem is the use of repetition, particularly the repeated image of the house. The house is both a physical place and a symbol for the speaker’s desire and longing. What inspired you to use the ghazal form for this particular poem, and how do you feel that the form influenced the content and tone of the piece?

JP: This is a poem about unrequited love, as are several others in the book. I think the ghazal felt right for this poem because the repetition felt like an insistence, like I was saying I love you over and over again and being answered with silence. For me, the image of the house—this sad little shack that was once full of life and is now abandoned, falling apart—was representative of what I thought was real, this idea of a relationship that wasn’t true, in the end. It was a daydream that saturated my life for a long time, and when I finally saw that it was something I had built in my head, it fell apart as if it had been put together with sticks and glue. The meaning of the house shifts throughout this poem, though. And this is something I love about writing in form: the ability to play, to find the places where the constraint can bend. In one couplet, the house becomes a verb (housed); in one, it’s the house of another man I spent time with while trying to move on. The poem ends by returning to the imagined version, the fantasy of the house and the lovers’ future there together.

SD: In Red Ocher, the centos serve as a structural seam that adds depth to the narrative form of the book. I found this aspect particularly intriguing. Could you share your experience in writing these centos and explain how you came to the realization that they can be a remarkable way to complicate the book’s narrative structure?

JP: The centos started as an exercise to think more closely about the line and what it can do, and at the beginning, I didn’t intend for them to become anything beyond that. But I found that through them, I was able to write about subjects that I was having trouble addressing directly at the time; the distance created by the form helped. Later, I wrote poems that were more direct, but the centos felt important in opening me up to that directness.

I really enjoyed the collage aspect of the cento. I had a large working document where I gathered lines I thought were beautiful or interesting, lines that felt like they had the potential to shift in meaning if they were placed within a different context. It’s a bit like working on a puzzle: finding the pieces that will fit together to create something new that can stand on its own. As the poems came together, I started noticing that most of them were held together by a similar voice, which felt like it came from the same family as the other poems I was writing. That’s what ultimately made me include them in the book; I thought they shared the same ground, came from the same emotional place even while they handled narrative differently.

SD: What are some of the challenges you faced while writing and publishing your first book, and how did you overcome them?

JP: For me, one of the challenging things about the first book was my impatience to get it out, to get it over with. But it will take as long as it takes—and that goes for the writing itself, but also (and this can be the more frustrating part) the process of finding a publisher. It’s a lot of waiting. And with poetry, which largely works on the contest model, it can be expensive. I hope this system changes; I know a lot of incredible writers who are being shut out because they can’t afford the submission fees. There are some resources out there, and hopefully more will emerge. Emily Stoddard organizes a support circle through her poetry bulletin (a great resource for info on manuscript submissions overall), which covers submission fees for those who need it. And Gasher Press runs a First Book Scholarship for emerging writers who have yet to publish a full-length collection. What’s been difficult for me throughout the process—from sending out the manuscript, to working with my publisher, and now to the marketing side of things—is separating all of that from the writing. It feels important to not let the business side of it affect the actual making of the thing, but then sometimes that’s easier said than done. I’m slowly learning, though.

SD: What do you hope readers will take away from your poetry, and how do you want your work to impact them emotionally and intellectually?

JP: I hope that some readers will recognize something of themselves in the poems. There are experiences in the book that were wrapped up in shame or embarrassment for a long time, and I hope that for someone reading who has experienced something similar, they might feel seen. Beyond that, I hold no particular hopes about how the book is read. Once the poems are on the page, it’s out of my hands in a lot of ways. And there’s relief in that letting go.

SD: The idea of relinquishing shame through reading and writing of poems is intriguing. Is this something you would like to elaborate on? I am interested in understanding the complexity of shame as an emotion and its relationship with fear. How did writing and confronting those fears play a role in your journey of letting go?

JP: I was thinking especially about the poem “Afterimage,” which most directly addresses an experience that, for a long time, was surrounded by feelings of shame and embarrassment. It’s one of the last poems I wrote in the book, because it took a lot of writing around the thing to get to a place where I felt comfortable just coming out and saying what happened (in this case, my first encounter with physical intimacy). The poem begins with a moment that gave me a bodily sensation of shame every time I remembered it; my face would flush, my stomach would sink, and I’d feel like I was back in that room where the memory takes place. But this poem felt healing for me, in the sense that by centering that moment, I was able to take back some of the power I thought I’d lost.

SD: What lies beyond the debut? While it may seem premature to anticipate what literary endeavors await in the future, I can’t help but express my enthusiasm for this captivating book, igniting my anticipation for the possibilities that lie ahead.

JP: I have a series of new poems that I’m excited about, but I’m still in the early stages of figuring out what the project is and what shape it will take. It continues with some of the themes that appear in Red Ocher: thinking about human-animal relationships, as well as the ways violence and care can overlap in troubling ways. The climate crisis is also very present in my mind (the county in Nebraska where I live was just designated a disaster area due to drought), and I’ve been writing more about that, especially from my place as an agricultural worker. But for right now, I’m trying not to get too caught up in one project—I’m just writing the poems that come to me, and I’ll figure out the rest later.

–

Jessica Poli is a writer, editor, and educator living in Lincoln, Nebraska. Her debut poetry collection, Red Ocher (University of Arkansas Press), was selected by Patricia Smith as a finalist for the 2023 Miller Williams Poetry Prize. She is the author of four chapbooks, including Canyons (BatCat Press, 2018) and The Egg Mistress, which won the 2012 Gold Line Press Poetry Chapbook Competition. Her work has appeared in Best New Poets, North American Review, and Poet Lore, among other places, and she has been the recipient of a Wilbur Gaffney Poetry Prize and a Vreeland Award.

Saddiq Dzukogi is a Nigerian poet and Asst. professor of English at Mississippi State University. He is the author of Your Crib, My Qibla (University of Nebraska Press, 2021), winner of the 2021 Derek Walcott Prize for Poetry, and the 2022 Julie Suk Award. He is the recipient of numerous fellowships from the Nebraska Art Council, the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Pen America, and Ebedi International Residency. His poetry is featured in various magazines including POETRY, Ploughshares, Kenyon Review, Poetry London, Guernica, Cincinnati Review, Gulf Coast, and Prairie Schooner. Saddiq lives and writes from Starkville, Mississippi.