by Montserrat Andrée Carty | Contributing Writer

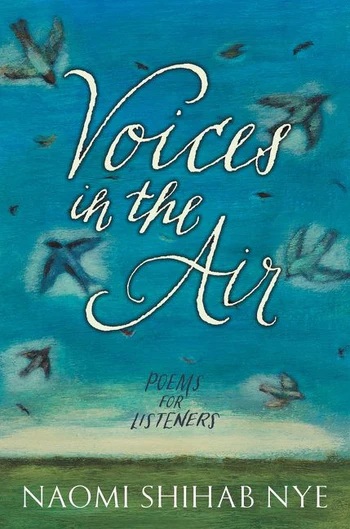

Like many people, I first discovered Naomi Shihab Nye through her poem “Kindness.” From there I fell in love with her words, and with her approach, as an artist, to the world. The way her warmth comes through on the page in a humble use of language, how she sees the ordinary as extraordinary, and the attention she gives to all beings, especially young people. The qualities that would make her the Poetry Foundation’s Young People’s Poet Laureate. Naomi herself has a youthful spirit, an openness that we often only find in the wisdom of children, but coupled with a deeper understanding of that wisdom—the kind that comes from life experience. She also inspires in the way she amplifies the voices of other writers and artists that have touched her. In Voices in the Air: Poems for Listeners (published in 2018 by Greenwillow Books), she gorgeously pays tribute to many of the voices she carries, people she feels are kindred—some she has known personally, some she has not—but who all opened something in her and in turn, in us, when we read these poems. Among those voices are Lucille Clifton, John O’Donohue, Maya Angelou, and her beloved father Aziz Shihab. Nye’s father was a Palestinian refugee and her mother an American of German and Swiss descent. She grew up in both Jerusalem and San Antonio, Texas. This cultural mix colors much of her work, in the most beautiful ways, dripping with love and curiosity. It is with the most tender heart that she writes about the Palestinian-Israeli conflict. In her poem “Blood” she writes: “I call my father, we talk around the news. / It is too much for him, / neither of his two languages can reach it.” It is this too muchness, the pain that language struggles to reach that Nye somehow manages to for us, with her own poems. In that same poem, she writes: “Today the headlines clot in my blood.” Nye is able to bring us beyond the headlines, beyond a country or city, into a house. Into a room, into a human heart—by zooming way in. By going granular, she takes us into the humanity of the people behind the headlines, and the lesson we so often come to after reading her generous poems: that we are all more alike than we might think. Her work is a call to compassion. At the ending of her poem, “Janna,” in her collection The Tiny Journalist (a 2019 collection inspired by “the Youngest Journalist in Palestine,” then-seven-year-old Janna Jihad Ayyad), Nye writes:

Why can’t they see

how beautiful we are?The saddest part?

We all could have had

twice as many friends.

For me, her description of what it is to live between cultures—“I’m not a full Arab, I’m not a full American. I always felt like I was a little bit on the sidelines”—resonates deeply. I live on the sidelines of my own cultures. Being made up of many places, people, and cultural experiences is what makes us feel on the sidelines, but is also precisely the fertile ground that sprouts deep listening to and astute observation of the world around us.

When it came to the chance to speak with Nye, I knew the cliché advice to not meet your heroes was one I would not heed. I had a hunch that we would connect—though I couldn’t have imagined that she’d become such an important person in my life. The beginning of our friendship was sparked by this very interview.

We don’t have to physically be with somebody to have that connection and kinship. During our first conversation over Zoom, Nye told me how she felt that connection with the late poet John O’Donohue as I now feel it with her, despite not yet having been in the same room together until recently. Nye is the embodiment of kindness—there have been days I’ve felt gloomy in spirit and that same day a surprise package will arrive from her. Dried beans, beeswax chapstick, blue corn flour pancake mix, and my day is turned around. Or a book of poetry from a poet I didn’t yet know, with a handwritten card. Perhaps the kindest of things she gifts, though, is a generosity of spirit.

She once told me I must get William Stafford’s books—Writing the Australian Crawl: Views on the Writer’s Vocation or You Must Revise Your Life. Just as William Stafford’s voice is one Nye carries, I now carry her voice with me in many ways. In her I’ve found a kindred spirit, who understands me, but knows a little better than me, too. To share her wisdom with me is one of the greatest kindnesses I have known.

Naomi Shihab Nye is a Palestinian-American poet, the Poetry Foundation’s Young People’s Poet Laureate, and previous editor of poems for the New York Times Sunday magazine. She has written or edited more than thirty books, including Cast Away, The Tiny Journalist, Voices in the Air, and Everything Comes Next. We began our conversation over Zoom, talking about our shared wandering spirit. This conversation first appeared on Musings of the Artist in an audio format. It has been transcribed here for Poetry Northwest.

I heard her say once that she has always felt like a wanderer, which resonated deeply, having not had one place to call home. And so, I ask her a question I am still trying to answer myself:

Montserrat Andrée Carty (MAC): How did you find your sense of home in the world?

Naomi Shihab Nye (NSN): Well, my parents, they were open to wandering. We would go on these family driving trips to different places. We did that when I was a child, and then we wandered in Europe and in the Middle East, and lived in the Middle East, and came back. When I got out of college, my family came to Texas. I took a job at the Texas Commission on the Arts. I said, “Yes, I can work for you and I’ll go from town to town, and be a visiting poet.” It was a fantastic life, a fantastic job. I loved every second of it, and I did it basically my entire adult life, in different ways. It was a great way to be out there in the world, going to these towns and being presented to large groups of kids in various environments. Then seeing, how could I make this thing that mattered so much to me, poetry, your own voice, spoken word, written word, be a positive experience for other kids? How could there be enthusiasm around that experience for everybody? For years I remember this girl, she might’ve been a 6th grader, when I was out in a small town called Albany, Texas. The first time I ever worked there, I was leaving town, after two weeks at the school and this girl chased my car—I saw her in the rearview mirror, waving. I opened the window and she said to me, “I just wanted to tell you that I had waited for you all my life. I always knew there had to be another poemist out there somewhere.” I thought, here was a child who really loved poetry and writing and she even had invented her own word, poemist. It was so charming. Just hearing that little child’s voice, I always knew there had to be another one out there somewhere. That’s happened every single place I’ve ever worked, whether in remote, rural Alaska, or an orphanage in Jordan. The sense of deep connection with kids keeps you going.

MAC: You have written about a pivotal moment in your childhood, when you wrote a poem that a girl who was older than you read and she said, “I know what you mean.” Isn’t so much of the reason that we create art and devour art so that we don’t feel alone and we can say to each other, “Me too, I know what you mean?” I’m moved by the fact that you found that realization early on, that it really sparked your own vocation and love for words and poetry.

NSN: Well, that’s so nice of you to notice that and to think about it. I do think that you can’t really get any better than that, someone saying to you, they know what you mean. I was in first grade and first grade was not going very well for me. I had had a few bad little episodes. I had done something on the first day I didn’t mean to do: contributed to someone breaking their nose, which was not a great thing on the first day of school. I was pinned by my teacher as a troublemaker, because I had poked someone with a pencil. I had a bad reputation and the teacher was not gracious to me. As far as I could tell school was going to be a long and durable experience and then my parents told me we were going off to Chicago for the weekend, on a train. I was just in my first few weeks of feeling that I could write, because we were just starting to write in first grade. I wanted to write a poem in the hotel room in Chicago to describe how astonishing and exhilarating the day had been. I wrote that poem and then I carried it back to first grade, gave it to my teacher. I remember thinking, even though I didn’t know this term yet, it’s like a peace offering. Maybe she’ll like me now, if I give her something. She read it distractedly and said, “Oh, that’s nice. You can hang it up in the hallway.” A few weeks later, this older girl whom I imagined as a third grader ran over to me and said, “Are you the person who wrote that poem about Chicago?” I said, “Yes.” She said, “I read it. I went there too. I know what you mean.” Here I was, a six-year-old, feeling a little bit lost. Suddenly, this older child just stared me in the eyes and said, I know what you mean. She ran off to the playground and lucky for me, I was a person who could detect my gifts when they were given because something inside me said, okay, that’s it. That’s what I’m going to do. I’m going to write things down. I want to do that all my life. That’s what I’m going to be. That’s who I am.

MAC: In one of your books, you point out this question that people ask: “what do you want to be?” They don’t ask “who” or “how do you want to be?” I typically ask, because people know you as your profession, but who are you beyond that? How do you move through the world?

NSN: I think I always saw myself as an observer. I always felt like my job is to be a witness. I’m not a full Arab, I’m not a full American. I always felt like I was a little bit on the sidelines, but I was in a spot where I had a good view. I could see what others did, I could watch, and I could absorb and put pieces together that made sense to me. That’s who I am. I knew it. I was confident in it. Even now my mother and I talk about it and she says, suddenly you just saw yourself as a writing person. It was your activity. It was what you did when you were at your desk alone and in your room. It went on from there. From the age of six, I was able to feel that others could know what you mean.

MAC: Who we are also has to do with the people we carry with us. In your book, Transfer, the way that you write about your father, I could see how much you love him. He just seemed so fiercely hopeful and joyous despite the hardship that he experienced. It seems that you carry those qualities as well. I was thinking about this when I was reading one of your poems, “Break the Worry Cocoon,” where you write: “How did you survive so much hurt and remain gracious?” Then of course, too, with your magnificent poem “Kindness.” Can you share the story behind this poem?

NSN: Yes. My dear Michael and I had gotten married and flown straight away to South America. We were young kids, naive, big dreams, big plans, and we had this somewhat ridiculous plan that he had made up that I just signed onto to travel the full length of South America from top to bottom by road. If you look at a map, that looks doable, but if you consider the details and the possibilities of trauma and tragedy that may occur along the way, there are many. We were robbed on one of the first buses that we took. It was very scary, a whole gang of robbers out in the countryside, in the mountains at night, in the country of Colombia. Then someone else who was on the bus, the Indian, the poor dear Indian whom I thought of all these years was murdered because he had nothing for them to take. I’d never been in a situation where someone was murdered. I realize lots of people have, in the world, been in that situation and it’s unthinkable. Going back to the town we had come from, where we’d actually gotten on the bus seemed like a better plan than going forward. We had nothing at this point, just nothing. We had no tickets, no money, no passports, nothing. Suddenly, you’re catapulted into this situation and it’s the days of pre-internet, and you don’t have a cell phone, and we knew no one. It was pretty daunting. We had to talk our way back onto the bus to go back to the town we had come from without having any money to pay them. We got back there and then various quick plans ensued. I ended up sitting alone in the plaza, in the town of Popayán, a beautiful town that would end up being devastated by an earthquake. It was like tragedy surrounded that place.

I’d always been a person who believed that if you were in a really bad place, you just needed to get very, very quiet and listen, and maybe ask a question into the air. Maybe some people would call it meditating, some would call it praying, beseeching, but you needed to quiet your mind. I heard this poem, and I heard it in this woman’s voice being spoken to me. I pulled that little notebook out. I wrote it down, as I heard it. I felt like a scribe in that moment. It was like nothing can get in the way of my copying this poem down right now, that’s what I’m here to do. After I finished writing the full draft, maybe two lines changed. Only a few words in them changed. Basically, I copied it down verbatim. I stood up, took a breath, put that notebook back in my pocket, felt as if a gift had been given, I had been there to receive it. Suddenly, I knew two things that I could do to survive at that moment. I could figure out how to carry on.

It was as if, listening for a poem in a time of extreme stress, I was given the poem of my lifetime, because I think without a doubt, I could make the generic statement that that’s been the poem that most people want. They want to copy it or put it in their anthologies or hang it on their refrigerator, or I get letters saying, “I read this poem to my friend whose son just died.” I’ve heard about this poem all my life now and I am very grateful for that. I don’t claim it still, to this day. I feel that it’s a poem that found its way to me.

I often have told kids that if you are a person in the habit of listening to yourself, to others, and then to your memory, then you may be more likely to hear other incredible things like a tree talk to you when you need a tree to talk to you, or the future give you a little bit of a direction. Maybe even you will hear a voice from your past giving you some guidance that you need right at that moment when you need it. I have felt that happen many times. I’m sure that it’s common that you suddenly hear the voice of your teacher from long ago. You haven’t even thought of that person in years, or seen them in many years, and suddenly, you hear something they used to suggest to their class and it comes back to you right when you needed it. There’s so much interesting listening that we can do. I think that kind of listening, it’s here to serve us, but also, we have to be ready for it.

MAC: Yes. You’ve been listening and paying attention, it seems like your whole life. Throughout your work, it’s clear that you notice the beauty of everyday things. In your poem “The Traveling Onion,” I love the line “all small forgotten miracles.” In your poem “Broken,” this also really pierced me: “Thank you ankles, thank you wrists, how many gifts have we not named?” I’ve always believed that there are so many quiet offerings all around us and that all we really have to do is pay attention to see them. I would love to hear a little bit more about your thoughts on these teeny miracles of the everyday, because I feel like that’s how we find meaning in our life.

NSN: Yes, it is how we find meaning and it costs nothing. We’re all in it all the time, but we’re so distractible. There are so many things that take us away from that quiet every single day. We wake up with our to-do lists imprinted on our brains. Many times, we just don’t take that quiet time, or what might be offered to us. I used to get in trouble a lot when I was a kid in elementary school for, well, what the teacher would call daydreaming. It was daydreaming, but I always felt that it was almost deeper. I remember wanting to respond and say something like, “Well, it’s not just daydreaming. I’m in a hypnotic trance, thinking about the blood inside my body right now, and all the different things it’s doing that I will never see. I just think it’s really important to thank that blood or be aware of that blood because we don’t even really feel it.” I remember having all these excuses in my mind for why I wasn’t paying attention in math or something because there was so much to think about. Of course, being in school in a class that you weren’t very interested in was a good place to do it as was writing poems in the margins of all my school notebooks, which I always did from first grade on, but that feeling of being transported by the miracle that we’re living inside of it every minute, and we often don’t even think about it.

MAC: It’s the biggest miracle. Recently I had pneumonia, and when it finally resolved, I felt this huge feeling of gratitude–and oh, like I was a different person almost. I had a newfound joy and gratefulness. Now here I am again, all nervous about a potentially scary thing I have to see the doctor about tomorrow. I’m back in the same worry loop of “Uh-oh.” I’m anxiety-prone anyway, I know a lot of people are. Our worry is just looking for somewhere to land. When I think of it that way, it helps me a little bit to dissolve the worry, because it’s like, okay, this is not really something I need to be focusing my attention on. It’s just that I have this in me, to fixate on something, and I’m choosing to look at this little thing right now. I keep thinking, how can I just stay in this place of gratitude all the time for my health? Be grateful that I no longer have pneumonia? How do we carry that gratitude and not just forget about it a week later?

NSN: It is hard for us as human beings to carry the gratitude long enough because of that distractible issue. We get distracted by our next worry or complaint or headline or what’s going on down the street or some crazy thing comes along and distracts us again. We slowly slide off the path of gratitude. I do think that the morning gratitude notebook, which is something that many people talk about, and many people do in the world, I think it’s a good tendency. I think that can be helpful because it reminds you on a daily basis of what you have. Again, you could do a morning and evening gratitude notebook. “That thing I worried about that was going to happen today didn’t happen.” It could be that simple.

MAC: Yes. I wanted to talk to you about your magnificent book of poems, Voices in the Air, on the people who stay with us—who has stayed with you? I love the feeling the title evokes. In the book you wrote a poem for the late John O’Donoghue. His work and his words have stayed with me for all these years as well. When you wrote that poem, you had never met him in person, right?

NSN: No, I never met him, we were pen pals. The irony is, so many people I know knew him. Some of my friends knew him intimately, knew him for years and drove buses for him on his retreats in Ireland. I could have known him and I wish, of course, that I had made an effort to go actually meet him, even when he was in the United States or in Ireland, either one, but being taken to his house after he died was just an overwhelmingly intense experience. To look through his windows after reading his letters for years. He was so sweet and tender and beautiful in his letters and he originally wrote to me asking if he could quote from my poems in his talks, or in a book or something, or if he could use them in his retreats. I said, “Of course, do whatever you want with them.” We just went back and forth like that, and then he would send me his books, and I would always be happy when I got this package tied up from Ireland. I wish I had known him, he was such a beloved man, but I do know him because I knew his voice.

MAC: Speaking of the people we carry close, in Voices in the Air you also write “people do not pass away, they die and then they stay,” which I wholeheartedly feel too. Whose voices do you continue to carry with you the most?

NSN: Thanks for mentioning those two things. I’ve always been very cognizant of voices in the air, although I don’t usually hear them as distinctly as I did with the “Kindness” poem, but without a doubt, I carry my father’s and I hear him all the time. For poets, I carry W.S. Merwin and William Stafford. Those were two of my favorite poets from my teenage years, whose voices live in me forever. I am such a grateful reader of their work. I had no idea that I would become personal friends with both of them. I feel very lucky to have known them. Also, so many women like Lucille Clifton, whom I valued her voice and her strength and her counsel, her mighty spirit. I feel like her voice is with me always. My Palestinian grandmother is with me, and even though we didn’t speak the same language, I feel that her perspective is with me. Those would be some of my main voices that I regularly listen to.

MAC: Beautiful. My own paternal grandmother sparked my love of cooking, writing, reading, music and creating. She too certainly wandered, she and my grandfather, they moved a lot. They were journalists. She was working for The New York Times, he was working for TIME and they moved to Bogota, Colombia, where they lived for many, many years—where my dad was born.

NSN: That’s fascinating, I did the “Kindness” poem coming out of Colombia too. I love hearing about her and that she’s so much with you, she’s in you. Isn’t it incredible how you’re manifesting her. That’s what I think about. One of the reasons I don’t like the phrase “somebody passes away,” it’s so flimsy, it’s so vague, it sounds just like a wisp in the wind. No, they don’t, they die and then they stay in so many ways within us, around us in everything they loved. I just feel very, very strongly about that, but in the manifestation of her, you are carrying her and she’s staying.

—

Naomi Shihab Nye is a Palestinian-American poet, previous editor of poems for the New York Times Sunday magazine, and from 2019-2021 she was the Poetry Foundation’s Young People’s Poet Laureate. Nye has written or edited more than thirty books, including Cast Away, The Tiny Journalist, Voices in the Air, and Everything Comes Next.

Montserrat Andrée Carty is a writer and photographer. In addition to writing and making photos, she hosts the podcast Musings of the Artist and is the Interviews Editor for Hunger Mountain. She is currently a MFA in Writing candidate at Vermont College of Fine Arts and is working on a hybrid essay collection on home and belonging.