by Han VanderHart | Contributing Writer

Fiona Sze-Lorrain is a poet, literary translator, editor, and zheng harpist who writes and translates in English, French, Chinese, and occasionally Spanish. One of the few English-language poets of our times who works across genres and artistic expressions, as well as more than three languages or cultures, she is the author of four books of poetry: Water the Moon (2010), My Funeral Gondola (2013), and more recently The Ruined Elegance (2016)—a finalist for the Los Angeles Times Book Prize—and Rain in Plural (2020), both from Princeton University Press. Sze-Lorrain has translated more than a dozen volumes of contemporary Chinese-language, French, and American poets, and guest/coedited three anthologies of international literature. She serves as an editor at Vif Éditions, a small independent press based in Paris.

A film on Sze-Lorrain’s poetry, translations, and zheng harp music, Rain in Plural . . . and Beyond, is now available to watch here. She presents her poems, including “Putin’s Dog” (“Not Meant as Poems”), first published here at Poetry Northwest. She also reads bilingual poems and translations of Chinese poets (including Ye Lijun—two translations can be read here) and American poet Mark Strand, as well as performs a classical piece High Moon on the guzheng.

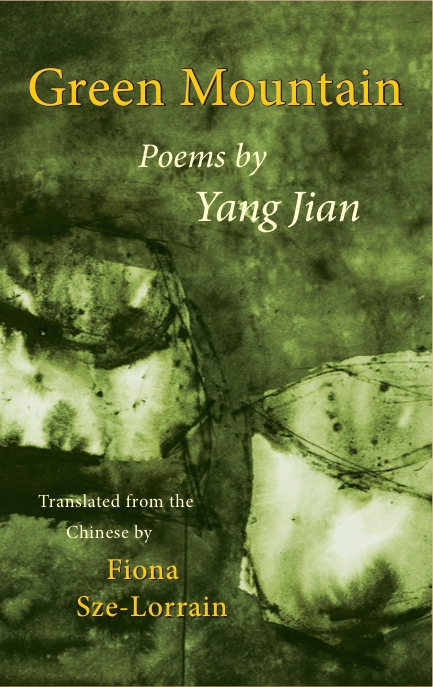

This conversation about translating Green Mountain by Yang Jian (MerwinAsia, 2020) took place with Han VanderHart over email in March 2021.

Han VanderHart: You said at a recent reading for your latest poetry collection Rain in Plural that one of your goals as a translator is to be invisible—and that invisibility is a gift. Would you say more about this formal invisibility, and your thoughts on “versions” or “after” translations?

Fiona Sze-Lorrain: Much of the mainstream culture does not value discretion. It capitalizes on loudness and visibility at first degree. I am generalizing hastily, of course. By invisibility, I don’t mean absence. Quite the contrary—invisibility is a form of presence. It invalidates the agency of justification or explanation. The act or action alone will speak for itself.

Translations can begin as close readings and interpretations, but that “method” may not suffice. Translation works best when a translator isn’t approaching the work as a consumerist reader, which is to say that sometimes the most meaningful translations aren’t the ones free of “errors” or “weakness,” whatever these terms mean. I find those “adapted” or edited “versions” somewhat hygienic for my tastes, like products that meet some criteria, or commodities of thought.

Translations that appeal most to me tend to contain a certain vulnerability or fragility, and elusiveness. In that sense, they aren’t just texts “in another language” and “from another culture,” but voices very much alive and nuanced. Instead of claiming or aspiring to erase distance, a deeper kind of translation makes us conscious of distance and proximity, and teaches us not to be afraid of distance. As far as I am concerned, intimacy can’t happen without distance or difference.

VanderHart: What were some of the special difficulties (or pleasures!) you encountered in translating Yang’s work, either in terms of specific poems, or more broadly as it applies to Yang’s body of work collected in Green Mountain?

Sze-Lorrain: The greatest pleasure is simplicity and precision. That is also a challenge, although I prefer not to see it as “difficult,” but “complex.” I practice austerity, which may not be in vogue at the moment.

VanderHart: In your introduction to Green Mountain, you write:

Like prayers and psalms, these poems further define an eloquence that embodies music and echoes. My decision to minimalize punctuation and create blank spaces between words in these translations is part of a search for such eloquence and soundscape.

You also mention the “naked” feeling of words in Yang’s poems, and the “honest” surface of the poet’s voice. What would you say to a reader anxious they are missing something by not being able to understand the original Chinese on the facing page?

Sze-Lorrain: I would say nothing.

VanderHart: The poem opening the collection “Station Platform, Early Spring,” features a spitting conductor who “mumbles” at the passengers “Come on, squeeze in, as if we were packing pigs” before “the train rattles away / in heavy white smoke.” Opening poems often have a special emphasis—might you say something about “Station Platform, Early Spring” being placed first? (You mention that the sixty poems comprising this bilingual edition were chosen collaboratively by yourself and Yang Jian.) It is an earthy beginning!

Sze-Lorrain: This is an observation of strong import. Yang Jian, like any other poet, isn’t one without contradictions. (In the poem “Ancient” he writes, “All my thoughts on immortality vanish in this contradictory yet unifying smell.”) I might not make rules like “Opening poems often have a special emphasis” or fixate opening poems as “first poems.” The link(s) between the opening piece and the next, and the ones after, is (are) quite specific in terms of imagery and poetic tone. Realities, too. Also, the choice of this opening poem can be more intuitive than say, intellectual or conceptual. At times it is liberating not to rationalize everything, but to leave some gap for the unknown and the unsaid. I would imagine the contact to be more generative if an opening poem stops the reader just as she/he turns the page to read the next, or if it catches her/him off guard, or as in your case, it lures you back to it—once you have read the work that comes straight after. What poetry would that be if a reader—or a poet, for that matter—claims to have understood everything of it?

VanderHart: What are your thoughts about the idea of the limit of language in Yang Jian’s work? For example, the poem “Record,” with the refrain “I can’t” (“I want to record the husks / but I can’t / I want to record them authentically / but I can’t”) or the poem “Survivor” which begins, “Language can’t reach / a fate that survives autumn rain.”

Sze-Lorrain: When the poet says “I can’t,” does that mean it is a limit of language? I see that as possibly eloquence. Even if it were a limit of language, might that be necessarily “bad” or “inadequate”? If something were perfect or without limits, would that be a soulful art?

I would like to cite some lines from Yang’s “Dusky Light”:

Of course, a soul exists in subtle ways

like an ancient jar in dead wall grass

The soul relies on a hole in the jar lid

relies on a strand of dusky light

to survive

and from his “Sorrow”:

I recall speeches by Plato and Seneca

Confucius’s teachings and Lao Zi’s silence

. . .

No masterpiece can make me forget the dark night

forget my folly, my riotous life

Language, like us humans, is supposed to have its limits. Otherwise, all we need is language (i.e. words or rhetoric), and not actions, emotions, nonempirical experiences, or even life in its broadest sense. Quoting Yang’s “All my thoughts on immortality vanish in a straw hut / where the floor is made of mud,” Christopher Merrill notes in his foreword, “and yet it is precisely here that the foul odor of tofu topped with rotten cabbage ushers him (the poet) into the eternal present, where everything—sight and sound, breath and touch—counts.” The idea is to acknowledge limits while working at language, or find ways to live with them, while creating instants of sublimity and lucidity, given the discomfort and liminality. That is poetry, or so I hope. I can’t speak for Yang, but I would like to think that I am political as much as lyrical, and not exactly fascinated by the romantic claims of poetry to immensity or infinite beauty, which could be no more than affirmation, self-congratulation, advertising and propaganda, or the safe curriculum taught in classrooms.

VanderHart: I find myself so interested in the ducks appearing throughout Green Mountain—particularly in the poems “Winter Duck Painting,” “Winter’s Day” and “In the Floating World.” Can you say something about the ducks?

Sze-Lorrain: The presence of ducks isn’t merely pictorial, as you have implied. They are as real and philosophical as one would like to make out of them. I enjoy listening to various interpretations of one of the guzheng classics from the Teochew school, 寒鸭戏水—literally translated as “Winter Ducks Playing with Water”—when I come across the ducks in these poems. Once in a while, I look at classical Chinese paintings of ducks, particularly those from the Ming era.

VanderHart: There is much natural imagery and landscape, but also industry (cement factories, cars, trains), in the poems of Green Mountain. Your introduction mentions that Yang Jian was a factory laborer himself before “earn[ing] a meager living through writing and painting.” I’m interested in Yang’s depiction of labor, and of writing as labor, and yet (again) the limits of language—or perhaps more particularly the language arts—as in this stanza from “Locked River Tower”:

Peasant workers are loading ore by the river

For a moment, I want to jump down

and work with them

But I stand on the tower

I’m a man who looks at the river

My books, my poems can never lessen their misery

Are there pointers you could offer to a reader thinking about labor and writing in Yang’s poetry?

Sze-Lorrain: The poet worked for thirteen years in an air compressor factory. He described his factory life as boring. As you can see from some of the poems, he depicts the lives of the rural working class as bleak, unjust, and to some extent, victimized. The poems suggest resignation (for example the ending line in “Toon Tree”: “What else can I do? Toon tree . . .!”), but a Chinese reader might notice in them traces of the Confucian notion “fate”—or dare I ask, “destiny”? Writing and painting, however, are paths that the poet has chosen and carved out for himself: they provide him a refuge and an outlet for expression, even though he continuously hints at a certain futility of words when confronted by social misery and emotional numbness.

VanderHart: The poem “Winter’s Day” contains the quatrain:

Had we known we were two lambs

on our way to slaughter

I’d weep, you’d also weep

in this floating world

The final line of “Winter’s Day” is closely echoed in the title of the poem “In the Floating World,” and American poetry readers might hear an echo of Lorine Niedecker’s “Paean to Place” (“O my floating life”) here. Thinking about the adjective of “floating” reminds me of Anne Carson, who writes “Nouns name the world. Verbs activate the names. Adjectives come from somewhere else. The word adjective is itself an adjective meaning ‘foreign.’ Adjectives, these small imported mechanisms, are the latches of being.” Do you have a theory of adjectives, at large and as regards Yang’s poetry particularly? Or additional thoughts on the word “floating,” which you discuss in your introduction?

Sze-Lorrain: Adjectives used to baffle me, though not as much as adverbs, but I am relearning them and accepting their tests. Could we have misunderstood them? I don’t know. Neither do I have a theory of adjectives. I hope this answer doesn’t disappoint. To perceive our worldly existence as “floating” is a Buddhist outlook. It has to do with impermanence. Yang writes in “An Old Couple’s Sutra”:

But the river won’t change its means

to reflect the moon

If impermanence still saddens me

I must be a fool

VanderHart: What is a question you wish I had asked about your translation of Yang Jian’s Green Mountain?

Sze-Lorrain: Ah, is this a trick question . . .

VanderHart: Because I selfishly want to know: what are some of your favorite translations?

Sze-Lorrain: Favorite translations or poems? In any case, here is one of my favorite stanzas, which is from “Country Chronicle”:

We walk, run—

slow punishment, slow

We’ve suffered

for a light departure

—

Han VanderHart lives in Durham, North Carolina. Han’s poetry, reviews, and essays have appeared in Poetry Daily, The Boston Globe, Kenyon Review, American Poetry Review, AGNI, Southern Humanities Review, Chattahoochee Review, Poetry Northwest, Poetry International, RHINO Poetry, Tinderbox Poetry Journal, The Greensboro Review and The Rumpus. Han is the author of the poetry chapbook Hands like Birds (Ethel Zine Press, 2019) and the poetry collection What Pecan Light (Bull City Press, Spring 2021). Their works-in-progress include the poetry collection Larks and the essay collection Confederate Monument Removal. Han is the reviews editor at EcoTheo Review and edits Moist Poetry Journal.